Arts & Letters, April 2018

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Bangla New Year<br />

Pahela Baishakh through the years<br />

•Binoy Dutta<br />

(Translated by Mir Arif )<br />

For Bangalis, Pahela Baishakh is one of the oldest<br />

and most celebrated festivals. The first day of the<br />

Bangla New Year in a Bangla calendar is known<br />

as Pahela Baishakh. Dating back to an early period<br />

in history, Pahela Baishakh has become a festival emanating<br />

from the heart of the whole Bangla-speaking world,<br />

irrespective of caste, creed and religious beliefs.<br />

The history of celebrating Pahela Baishakh is very old.<br />

Dividing a year into 12 months is an old practice according<br />

to the Hindu calendar. But during Mughal rule in India,<br />

Emperor Akbar ordered that the Bangla year be counted<br />

combining the Arabic calendar from March 10 or March<br />

11 in 1584. Though originally called a Fosholi Shon (crop<br />

year), it later gained currency as the Bangla year.<br />

In Akbar’s days, the economy of undivided Bengal was<br />

solely based on agriculture, with most people making<br />

their living through agricultural work of one kind or the<br />

other. Some people did enter other professions, but they,<br />

too, worked in the fields for a brief period of time. Farmers<br />

did not have any cash till the crops were harvested;<br />

so they had to buy daily necessaries all the year round on<br />

credit from shopkeepers. Since all the dues were cleared<br />

up toward the end of the year, shopkeepers tracked the<br />

sales on credit in a ledger book known as the “halkhata.”<br />

After previous dues were cleared up, a new ledger book<br />

opened and each farmer had a fresh entry on the book for<br />

the new year, and the whole process would then start all<br />

over again. So, creditors arranged a celebration honoring<br />

the farmers who lived up to their promises of paying the<br />

dues after the harvest, a custom observed in many parts<br />

of Bangladesh to this day. This celebration diversified over<br />

the centuries and became widely popular among all sections<br />

of society. In Bangladesh, Chhayanaut took an initiative<br />

to popularize this festival, turning it into a celebration<br />

of greeting the new Bangla year. It was also a time when<br />

Pakistani military rulers were contemptuous toward any<br />

manifestation of our secular culture.<br />

Pahela Baishakh now is a universal phenomenon<br />

among Bangalis. The first day of the Bangla calendar is<br />

celebrated in big cities with much fanfare, music and a<br />

feast of various local cuisines, and with high hopes that<br />

the Bangla New Year will bring prosperity and happiness<br />

for all.<br />

Pahela Baishakh is celebrated all over the country at<br />

city, district, union and upazila levels. With the crack of<br />

dawn, a tinge of festivity spreads in every nook and cranny<br />

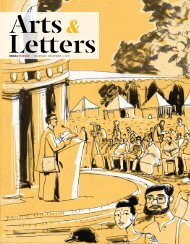

of the country. In the capital city, Chhayanaut opens<br />

the festivity at the Batamul (under the banyan tree) in<br />

Ramna Park with a number of impeccable musical renditions<br />

composed by five of the best poets and lyricists in<br />

the Bangla language (Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul<br />

Islam, Dwijendralal Roy, Rajanikanta Sen and Atul Prasad<br />

Sen). Large numbers of crowds throng the park to greet<br />

the new year with Chhayanaut. The celebration of the<br />

Bangla New Year and Chhayanaut’s programs are now inseparably<br />

connected.<br />

4<br />

Chhayanaut first celebrated the Bangla New Year in<br />

The festival, in its current<br />

form, indeed fosters a<br />

non-communal spirit and a<br />

cultural openness ingrained<br />

in our culture<br />

1967 (1374 in the Bangla calendar) under the ashwatha<br />

tree in Ramna Park. Except in 1971, the year that saw the<br />

Liberation War, Chhayanaut has been celebrating the day<br />

religiously with musical renditions and poetic recitations.<br />

Besides Chhayanaut’s program, a colorful, ceremonious<br />

procession welcoming the new year is brought out from<br />

the Institute of Fine <strong>Arts</strong> (Charukola Institute), University<br />

of Dhaka. Known as the “Mangal Shobhajatra,” it was first<br />

brought out in 1989 in the hope of ousting despotic forces<br />

from the country’s politics, seeking peace and justice for<br />

all. Charupith, a regional cultural organization, had earlier<br />

brought out a similar procession in 1986. Inspired by<br />

this, one of its initiators, Jamal Shamim, who enrolled in a<br />

master’s degree course at Dhaka University, started this at<br />

Charukala with replicas of horse, elephant, etc.<br />

Since 1991, Charukola Institute has been bringing out<br />

the procession with massive replicas of elephants, tigers<br />

that have added new hues to this carnival, enriching it<br />

each year with more and more replicas, handicrafts and<br />

masks of birds, owls, crocodiles, earthen dolls, oxcarts,<br />

palanquins, boats, hand fans -- everything crafted in sync<br />

with the tenets of local, indigenous cultures. UNESCO has<br />

incorporated this procession in its “Representative List of<br />

Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity” in 2016.<br />

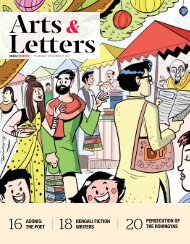

Apart from these, the entire city buzzes with programs<br />

and arrangements marking the day. In the old part of the<br />

city, businessmen and traders remain busy all day with<br />

PHOTO: MEHEDI HASAN<br />

halkhata festivities. The Baishakh fair in the field of Dhupkhola<br />

demonstrates how much passionate Bangalis are<br />

about festivals. The TSC area of Dhaka University vibrates<br />

with music and thousands of men and women, mostly<br />

young, hanging around in groups wearing colorful dresses.<br />

Women prefer green saris with red lining, and men<br />

green and red Punjabis, reflecting the colors of Bangladesh’s<br />

national flag. Now each area in the city has its own<br />

set of programs. Among others, the cultural programs at<br />

Rabindra Sarobar in Dhanmondi have gained some prominence<br />

in recent times.<br />

Pahela Baishakh is not celebrated only in Dhaka; it is<br />

celebrated with equal pomp and fanfare in other parts<br />

of the country as well. People from the Chittagong Hill<br />

Tracts also celebrate the day with various indigenous programs<br />

of their own. Boishukh by the Tripura, Sangrain by<br />

the Marma and Biju by the Chakma are three such programs<br />

to mark this day. In recent years, the three communities<br />

have celebrated this day together, which is called<br />

“Boishabi.” One of the main aspects of Boishabi is a water<br />

festival by the Marmas, which sees young boys and girls<br />

splashing water on each other, signifying their coming of<br />

age. The communal pressure that the Pakistani military<br />

rulers put on our culture and language rather stoked the<br />

spirit of this festival into a big national event.<br />

The festival, in its current form, indeed fosters a<br />

non-communal spirit and a cultural openness ingrained<br />

in our culture. Communal forces, however, have been at<br />

work to foil the festivities of this day. A bomb attack was<br />

also carried out on Chhayanaut’s program in Ramna in<br />

2001, leaving 10 people killed and over 50 injured. But the<br />

irony is, the following years saw the biggest congregation<br />

of cultural activists and common people who gathered<br />

there defying all threats of violence. •<br />

Binoy Dutta is a journalist and littérateur.<br />

ARTS & LETTERS SATURDAY, APRIL 14, <strong>2018</strong> | DHAKA TRIBUNE