BusinessDay 21 Aug 2018

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Tuesday <strong>21</strong> <strong>Aug</strong>ust <strong>2018</strong><br />

Nigeria’s population: Asset or liability<br />

Continued from back page<br />

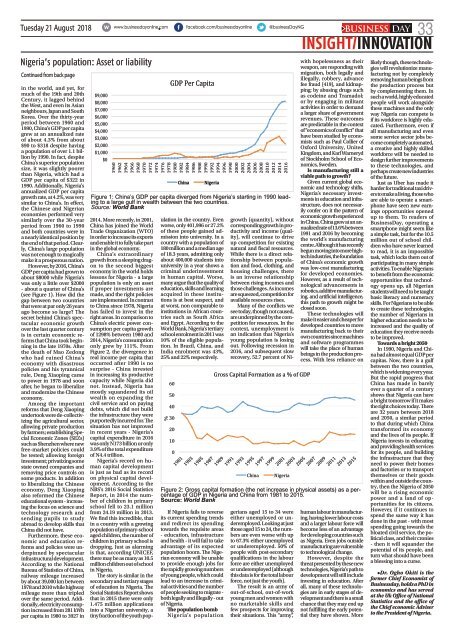

in the world, and yet, for<br />

much of the 19th and 20th<br />

Century, it lagged behind<br />

the West, and even its Asian<br />

neighbours, Japan and South<br />

Korea. Over the thirty-year<br />

period between 1960 and<br />

1990, China’s GDP per capita<br />

grew at an annualized rate<br />

of about 4.3% from about<br />

$90 to $318 despite having<br />

a population of over 1.1 billion<br />

by 1990. In fact, despite<br />

China’s superior population<br />

size, it was slightly poorer<br />

than Nigeria, which had a<br />

GDP per capita of $322 in<br />

1990. Additionally, Nigeria’s<br />

annualized GDP per capita<br />

growth rate, at 4.2%, was very<br />

similar to China’s. In effect,<br />

the Chinese and Nigerian<br />

economies performed very<br />

similarly over the 30-year<br />

period from 1960 to 1990<br />

and both countries were in<br />

a nearly identical position by<br />

the end of that period. Clearly,<br />

China’s large population<br />

was not enough to magically<br />

make it a prosperous nation.<br />

However, by 2016, China’s<br />

GDP per capita had grown to<br />

about $8000 while Nigeria’s<br />

was only a little over $2000<br />

- about a quarter of China’s<br />

(see Figure 1). How did the<br />

gap between two countries<br />

that were at par only 26 years<br />

ago become so large? The<br />

secret behind China’s spectacular<br />

economic growth<br />

over the last quarter century<br />

is in certain economic reforms<br />

that China took beginning<br />

in the late 1970s. After<br />

the death of Mao Zedong<br />

who had ruined China’s<br />

economy with disastrous<br />

policies and his tyrannical<br />

rule, Deng Xiaoping came<br />

to power in 1978 and soon<br />

after, he began to liberalize<br />

and modernize the Chinese<br />

economy.<br />

Among the important<br />

reforms that Deng Xiaoping<br />

undertook were de-collectivizing<br />

the agricultural sector,<br />

allowing private production<br />

by farmers; establishing Special<br />

Economic Zones (SEZs)<br />

such as Shenzhen where new<br />

free-market policies could<br />

be tested; allowing foreign<br />

investment; privatizing some<br />

state owned companies and<br />

removing price controls on<br />

some products. In addition<br />

to liberalizing the Chinese<br />

economy, Deng Xiaoping<br />

also reformed the Chinese<br />

educational system - increasing<br />

the focus on science and<br />

technology research and<br />

sending pupils to study<br />

abroad to develop skills that<br />

China did not have.<br />

Furthermore, these economic<br />

and education reforms<br />

and policies were underpinned<br />

by spectacular<br />

infrastructural development.<br />

According to the National<br />

Bureau of Statistics of China,<br />

railway mileage increased<br />

by about 39,000 km between<br />

1978 and 2010 while highway<br />

mileage more than tripled<br />

over the same period. Additionally,<br />

electricity consumption<br />

increased from 281 kWh<br />

per capita in 1980 to 3927 in<br />

$9,000 <br />

$8,000 <br />

$7,000 <br />

$6,000 <br />

$5,000 <br />

$4,000 <br />

$3,000 <br />

$2,000 <br />

$1,000 <br />

$0 <br />

1960 <br />

1962 <br />

1964 <br />

1966 <br />

1968 <br />

1970 <br />

1972 <br />

1974 <br />

1976 <br />

1978 <br />

1980 <br />

1982 <br />

1984 <br />

1986 <br />

1988 <br />

1990 <br />

1992 <br />

1994 <br />

1996 <br />

1998 <br />

2000 <br />

2002 <br />

2004 <br />

2006 <br />

2008 <br />

2010 <br />

2012 <br />

2014 <br />

2016 <br />

Figure 1: China’s GDP per capita diverged from Nigeria’s starting in 1990 leading<br />

to a large gulf in wealth between the two countries.<br />

Source: World Bank<br />

GDP Per Capita <br />

China <br />

Nigeria <br />

2014. More recently, in 2001,<br />

China has joined the World<br />

Trade Organization (WTO)<br />

in order to increase its exports<br />

and enable it to fully take part<br />

in the global economy.<br />

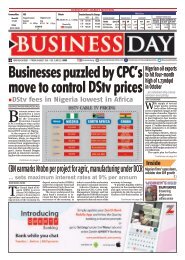

China’s extraordinary<br />

growth from a sleeping dragon<br />

to the second biggest<br />

economy in the world holds<br />

lessons for Nigeria - a large<br />

population is only an asset<br />

if proper investments are<br />

made, and the right policies<br />

are implemented. In contrast<br />

to China since 1978, Nigeria<br />

has failed to invest in the<br />

right areas. In comparison to<br />

China’s electric power consumption<br />

per capita growth<br />

of 1298% between 1980 and<br />

2014, Nigeria’s consumption<br />

only grew by 111%. From<br />

Figure 2, the divergence in<br />

real income per capita that<br />

occurred after 1990 is no<br />

surprise - China invested<br />

in increasing its productive<br />

capacity while Nigeria did<br />

not. Instead, Nigeria has<br />

mostly squandered its oil<br />

wealth on expanding the<br />

civil service and on paying<br />

debts, which did not build<br />

the infrastructure they were<br />

purportedly incurred for. The<br />

situation has not improved<br />

in recent years - Nigeria’s<br />

capital expenditure in 2016<br />

was only N173 billion or only<br />

3.9% of the total expenditure<br />

of N4.4 trillion.<br />

Nigeria’s record on human<br />

capital development<br />

is just as bad as its record<br />

on physical capital development.<br />

According to the<br />

NBS’s 2016 Social Statistics<br />

Report, in 2014 the number<br />

of children in primary<br />

school fell to 23.1 million<br />

from 24.19 million in 2013.<br />

We find this incredible, that<br />

in a country with a growing<br />

population of primary-school<br />

aged children, the number of<br />

children in primary school is<br />

dropping. Just as alarming<br />

is that, according UNICEF,<br />

there may be as many as 10.5<br />

million children out of school<br />

in Nigeria.<br />

The story is similar in the<br />

secondary and tertiary stages<br />

of education in Nigeria. The<br />

Social Statistics Report shows<br />

that in 2015 there were only<br />

1.475 million applications<br />

into a Nigerian university, a<br />

tiny fraction of the youth population<br />

in the country. Even<br />

worse, only 401,996 or 27.2%<br />

of these people gained admission<br />

into university. In a<br />

country with a population of<br />

180 million and a median age<br />

of 18.3 years, admitting only<br />

about 400,000 students into<br />

university in a year shows a<br />

criminal underinvestment<br />

in human capital. Worse,<br />

many argue that the quality of<br />

education, skills and learning<br />

acquired in these institutions<br />

is at best suspect, and<br />

at worst, non comparable to<br />

institutions in African countries<br />

such as South Africa<br />

and Egypt. According to the<br />

World Bank, Nigeria’s tertiary<br />

school enrolment in 2011 was<br />

10% of the eligible population.<br />

In Brazil, China, and<br />

India enrolment was 43%,<br />

25% and 22% respectively.<br />

% <br />

60 <br />

50 <br />

40 <br />

30 <br />

20 <br />

10 <br />

0 <br />

1981 <br />

1983 <br />

Gross Capital Formation as a % of GDP <br />

1985 <br />

1987 <br />

1989 <br />

1991 <br />

1993 <br />

1995 <br />

China <br />

1997 <br />

1999 <br />

2001 <br />

Nigeria <br />

BUSINESS DAY 33<br />

INSIGHT/INNOVATION<br />

2003 <br />

2005 <br />

2007 <br />

2009 <br />

2011 <br />

2013 <br />

2015 <br />

Figure 2: Gross capital formation (the net increase in physical assets) as a percentage<br />

of GDP in Nigeria and China from 1981 to 2015.<br />

Source: World Bank<br />

If Nigeria fails to reverse<br />

its current spending trends<br />

and redirect its spending<br />

towards the requisite areas<br />

- education, infrastructure<br />

and health - it will fail to take<br />

advantage of its expected<br />

population boom. The Nigerian<br />

economy will be unable<br />

to provide enough jobs for<br />

the rapidly growing numbers<br />

of young people, which could<br />

lead to an increase in criminal<br />

activities and the number<br />

of people seeking to migrate -<br />

both legally and illegally - out<br />

of Nigeria.<br />

The population bomb<br />

Nigeria’s population<br />

gerians aged 15 to 34 were<br />

either unemployed or underemployed.<br />

Looking at just<br />

those aged 15 to 24, the numbers<br />

are even worse with up<br />

to 67.3% either unemployed<br />

or underemployed. 50% of<br />

people with post-secondary<br />

qualifications in the labour<br />

force are either unemployed<br />

or underemployed (although<br />

this data is for the total labour<br />

force, not just the youth).<br />

The result is an army of<br />

out-of-school, out-of-work<br />

young men and women with<br />

no marketable skills and<br />

few prospects for improving<br />

their situations. This “army”,<br />

growth (quantity), without<br />

corresponding growth in productivity<br />

and income (quality),<br />

will continue to drive<br />

up competition for existing<br />

natural and fiscal resources.<br />

While there is a direct relationship<br />

between population<br />

and food, clothing, and<br />

housing challenges, there<br />

is an inverse relationship<br />

between rising incomes and<br />

those challenges. As incomes<br />

are squeezed, competition for<br />

available resources rises.<br />

Many of the conflicts we<br />

see today, though not caused,<br />

are underpinned by the competition<br />

for resources. In the<br />

context, unemployment is<br />

an indication that Nigeria’s<br />

young population is losing<br />

out. Following recession in<br />

2016, and subsequent slow<br />

recovery, 52.7 percent of Niwith<br />

hopelessness as their<br />

weapon, are responding with<br />

migration, both legally and<br />

illegally, robbery, advance<br />

fee fraud (419), and kidnapping;<br />

by abusing drugs such<br />

as codeine and Tramadol;<br />

or by engaging in militant<br />

activities in order to demand<br />

a larger share of government<br />

revenues. These outcomes<br />

are predictable in the context<br />

of “economics of conflict” that<br />

have been studied by economists<br />

such as Paul Collier of<br />

Oxford University, United<br />

Kingdom, and Karl Warneryd<br />

of Stockholm School of Economics,<br />

Sweden.<br />

Is manufacturing still a<br />

viable path to growth?<br />

Given current global economic<br />

and technology shifts,<br />

Nigeria’s necessary investments<br />

in education and infrastructure,<br />

does not necessarily<br />

confer on it the pattern of<br />

economic growth experienced<br />

in China. China grew at an annualized<br />

rate of 13.6% between<br />

1991 and 2016 by becoming<br />

the world’s manufacturing<br />

centre. Although it has recently<br />

begun moving into more hightech<br />

industries, the foundation<br />

of China’s economic growth<br />

was low-cost manufacturing<br />

for developed economies.<br />

However, as a result of technological<br />

advancements in<br />

robotics, additive manufacturing,<br />

and artificial intelligence,<br />

this path to growth might be<br />

closed soon.<br />

These technologies will<br />

make it easier and cheaper for<br />

developed countries to move<br />

manufacturing back to their<br />

own countries since machines<br />

and software programmes<br />

will take the place of human<br />

beings in the production process.<br />

With less reliance on<br />

human labour in manufacturing,<br />

having lower labour costs<br />

and a larger labour force will<br />

become less of an advantage<br />

for developing countries such<br />

as Nigeria. Even jobs outside<br />

manufacturing are vulnerable<br />

to technological change.<br />

However, despite the<br />

threat presented by these new<br />

technologies, Nigeria’s path to<br />

development will still include<br />

investing in education. After<br />

all, many of these technologies<br />

are in early stages of development<br />

and there is a small<br />

chance that they may end up<br />

not fulfilling the early potential<br />

they have shown. More<br />

likely though, these technologies<br />

will revolutionize manufacturing<br />

not by completely<br />

removing human beings from<br />

the production process but<br />

by complementing them. In<br />

such a world, highly educated<br />

people will work alongside<br />

these machines and the only<br />

way Nigeria can compete is<br />

if its workforce is highly educated.<br />

Furthermore, even if<br />

all manufacturing and even<br />

some service sector jobs become<br />

completely automated,<br />

a creative and highly skilled<br />

workforce will be needed to<br />

design further improvements<br />

to these technologies, and<br />

perhaps create new industries<br />

of the future.<br />

Just as Uber has made it<br />

harder for traditional taxi drivers<br />

to make a living, those who<br />

are able to operate a smartphone<br />

have seen new earnings<br />

opportunities opened<br />

up to them. To readers of<br />

<strong>BusinessDay</strong>, operating a<br />

smartphone might seem like<br />

a simple task, but for the 10.5<br />

million out of school children<br />

who have never learned<br />

to read, it is an impossible<br />

task, which locks them out of<br />

participating in many simple<br />

activities. To enable Nigerians<br />

to benefit from the economic<br />

opportunities that technology<br />

opens up, all Nigerian<br />

students will need to be taught<br />

basic literacy and numeracy<br />

skills. For Nigerians to be able<br />

to create these technologies,<br />

the number of Nigerians in<br />

higher education needs to be<br />

increased and the quality of<br />

education they receive needs<br />

to be improved.<br />

Towards a bright 2050<br />

In 1990, Nigeria and China<br />

had almost equal GDP per<br />

capitas. Now, there is a gulf<br />

between the two countries,<br />

which is widening every year.<br />

But the rapid progress that<br />

China has made in barely<br />

over a quarter of a century<br />

shows that Nigeria can have<br />

a bright tomorrow if it makes<br />

the right choices today. There<br />

are 32 years between <strong>2018</strong><br />

and 2050, a similar period<br />

to that during which China<br />

transformed its economy<br />

and the lives of its people. If<br />

Nigeria invests in educating<br />

and providing health services<br />

for its people, and building<br />

the infrastructure that they<br />

need to power their homes<br />

and factories or to transport<br />

themselves or their goods<br />

within and outside the country,<br />

then the Nigeria of 2050<br />

will be a rising economic<br />

power and a land of opportunities<br />

for its citizens.<br />

However, if it continues to<br />

spend the same way it has<br />

done in the past - with most<br />

spending going towards the<br />

bloated civil service, the political<br />

class, and their cronies<br />

- then it will squander the<br />

potential of its people, and<br />

turn what should have been<br />

a blessing into a curse.<br />

•Dr. Ogho Okiti is the<br />

former Chief Economist of<br />

Businessday, holds a PhD in<br />

economics and has served<br />

at the Uk Office of National<br />

Statistics and the office of<br />

the Chief economic Adviser<br />

to the President of Nigeria.