Viva Brighton Issue #68 October 2018

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

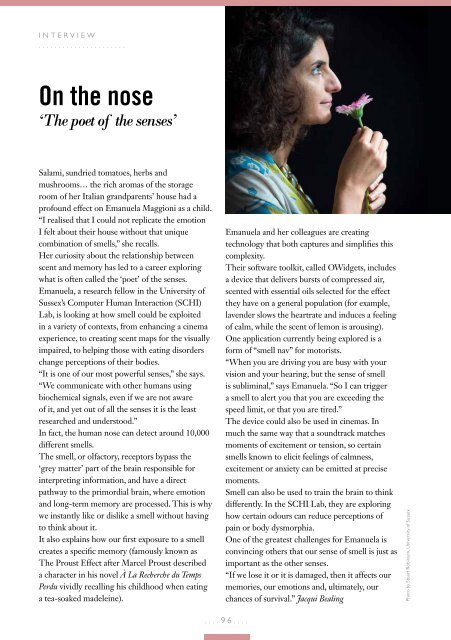

INTERVIEW<br />

......................<br />

On the nose<br />

‘The poet of the senses’<br />

Salami, sundried tomatoes, herbs and<br />

mushrooms… the rich aromas of the storage<br />

room of her Italian grandparents’ house had a<br />

profound effect on Emanuela Maggioni as a child.<br />

“I realised that I could not replicate the emotion<br />

I felt about their house without that unique<br />

combination of smells,” she recalls.<br />

Her curiosity about the relationship between<br />

scent and memory has led to a career exploring<br />

what is often called the ‘poet’ of the senses.<br />

Emanuela, a research fellow in the University of<br />

Sussex’s Computer Human Interaction (SCHI)<br />

Lab, is looking at how smell could be exploited<br />

in a variety of contexts, from enhancing a cinema<br />

experience, to creating scent maps for the visually<br />

impaired, to helping those with eating disorders<br />

change perceptions of their bodies.<br />

“It is one of our most powerful senses,” she says.<br />

“We communicate with other humans using<br />

biochemical signals, even if we are not aware<br />

of it, and yet out of all the senses it is the least<br />

researched and understood.”<br />

In fact, the human nose can detect around 10,000<br />

different smells.<br />

The smell, or olfactory, receptors bypass the<br />

‘grey matter’ part of the brain responsible for<br />

interpreting information, and have a direct<br />

pathway to the primordial brain, where emotion<br />

and long-term memory are processed. This is why<br />

we instantly like or dislike a smell without having<br />

to think about it.<br />

It also explains how our first exposure to a smell<br />

creates a specific memory (famously known as<br />

The Proust Effect after Marcel Proust described<br />

a character in his novel À La Recherche du Temps<br />

Perdu vividly recalling his childhood when eating<br />

a tea-soaked madeleine).<br />

Emanuela and her colleagues are creating<br />

technology that both captures and simplifies this<br />

complexity.<br />

Their software toolkit, called OWidgets, includes<br />

a device that delivers bursts of compressed air,<br />

scented with essential oils selected for the effect<br />

they have on a general population (for example,<br />

lavender slows the heartrate and induces a feeling<br />

of calm, while the scent of lemon is arousing).<br />

One application currently being explored is a<br />

form of “smell nav” for motorists.<br />

“When you are driving you are busy with your<br />

vision and your hearing, but the sense of smell<br />

is subliminal,” says Emanuela. “So I can trigger<br />

a smell to alert you that you are exceeding the<br />

speed limit, or that you are tired.”<br />

The device could also be used in cinemas. In<br />

much the same way that a soundtrack matches<br />

moments of excitement or tension, so certain<br />

smells known to elicit feelings of calmness,<br />

excitement or anxiety can be emitted at precise<br />

moments.<br />

Smell can also be used to train the brain to think<br />

differently. In the SCHI Lab, they are exploring<br />

how certain odours can reduce perceptions of<br />

pain or body dysmorphia.<br />

One of the greatest challenges for Emanuela is<br />

convincing others that our sense of smell is just as<br />

important as the other senses.<br />

“If we lose it or it is damaged, then it affects our<br />

memories, our emotions and, ultimately, our<br />

chances of survival.” Jacqui Bealing<br />

Photo by Stuart Robinson, University of Sussex<br />

....96....