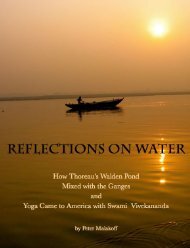

How Thoreau's Walden Pond Mixed with the Ganges and Yoga Came to America with Swami Vivekananda

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century. When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges." This book tells the story of these waters . . .

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.

I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges."

This book tells the story of these waters . . .

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Cybernii<br />

Cybernetics is <strong>the</strong> study of self-regulating mechanisms. It is a field that operates<br />

on <strong>the</strong> basis of perceived ‘mistakes’ <strong>and</strong> subsequent corrections. Cybernetics is<br />

rooted in <strong>the</strong> meaning of <strong>the</strong> nautical term-Cybernos, <strong>the</strong> Greek word for <strong>the</strong><br />

helmsman, <strong>the</strong> person who steers <strong>the</strong> boat. Cybernii is <strong>the</strong> plural form of <strong>the</strong><br />

word.<br />

I once had dinner <strong>with</strong> Buckminster Fuller. Soon after we sat down <strong>to</strong> dinner<br />

<strong>and</strong> ordered our meals, Fuller made <strong>the</strong> following comment, “A drunk helmsman,<br />

makes less mistakes than a sober helmsman.” Puzzled by this, I interjected,<br />

"Bucky, I wouldn't want <strong>to</strong> be in a boat or any o<strong>the</strong>r vehicle <strong>with</strong> a drunk at <strong>the</strong><br />

wheel." "Yes", he said <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n paused, letting his words sink in <strong>and</strong> looking at<br />

me, his eyes large through his thick glasses. Then, seeing no comprehension on<br />

my side, he continued, "That is <strong>the</strong> point. Unless you make a mistake, you will<br />

not correct <strong>the</strong> course. The more mistakes you make, <strong>the</strong> more possible corrections<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> more corrections you make, <strong>the</strong> more true your course."<br />

I immediately realized he agreed <strong>with</strong> my objection <strong>to</strong> being in a boat or a<br />

car <strong>with</strong> a drunk at <strong>the</strong> wheel, but for a different reason – <strong>the</strong> drunk did not<br />

make enough mistakes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>refore not enough corrections. That was why he<br />

drove down <strong>the</strong> road erratically, swaying from side <strong>to</strong> side. Fuller was suggesting<br />

not only that mistakes were good, but, <strong>the</strong> recognition of mistakes is <strong>the</strong> necessary<br />

prerequisite for any <strong>and</strong> all corrections!<br />

Related Glossary Terms<br />

Buckminster Fuller<br />

Index<br />

Find Term<br />

Section 4 - Acknowledgements