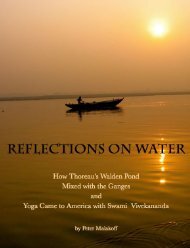

How Thoreau's Walden Pond Mixed with the Ganges and Yoga Came to America with Swami Vivekananda

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century. When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges." This book tells the story of these waters . . .

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.

I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges."

This book tells the story of these waters . . .

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

So, I left <strong>the</strong> technologically sophisticated, electricity always on, everything<br />

works, infra-structurally developed, relatively sanitized, small animals on<br />

leashes <strong>and</strong> large ones on farms, trash can clean, poverty is hidden,<br />

guaranteed your money back culture of <strong>the</strong> West <strong>and</strong> went <strong>to</strong> live in India;<br />

where <strong>the</strong> electricity cannot be depended on, many things do not work or are<br />

poorly built (except <strong>the</strong> ancient temples), you bought it you own it, trash is<br />

strewn about everywhere <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re are few or no trash-cans, beggars <strong>and</strong><br />

cows w<strong>and</strong>er <strong>the</strong> streets; <strong>the</strong>re are uncared-for dogs <strong>and</strong> gangs of monkeys<br />

that wreck everything, an undeveloped infrastructure <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> many<br />

technologies developed before electricity are more commonly used. Of course,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are exceptions, especially in certain parts of <strong>the</strong> big cities. But for <strong>the</strong><br />

most part, it was like leaving a world run by <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>and</strong> ideals <strong>and</strong> coming<br />

<strong>to</strong> live in <strong>the</strong> realm of <strong>the</strong> whole body, exposed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> elements.<br />

Like <strong>the</strong> West, India is also a realm of sex, violence, death <strong>and</strong> rebirth.<br />

Only here, <strong>the</strong>re is more of it <strong>and</strong> much of that is out in <strong>the</strong> open. None of<br />

this is <strong>to</strong> say that India is <strong>to</strong> be avoided . . . on <strong>the</strong> contrary, India is <strong>the</strong> most<br />

fertile ground for living that I know of. There are rare fruits <strong>and</strong> exquisite<br />

knowledge here. One must know what <strong>to</strong> look for, have good reason <strong>to</strong> do so<br />

<strong>and</strong> be very, very patient – for even <strong>the</strong> concept of time is different here; it is<br />

not oriented around a clock, but ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> moon, <strong>the</strong> sun, <strong>the</strong> seasons <strong>and</strong><br />

religious holidays; which brings me <strong>to</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r reason I came <strong>to</strong> India, it is<br />

very inexpensive <strong>to</strong> live here. I need only a few hours of <strong>the</strong> day <strong>to</strong> make a<br />

living, allowing me much free time, a rare commodity in <strong>the</strong> West. Time offers<br />

me <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>to</strong> consider <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> opportunity <strong>to</strong> create. The Mahabharata, <strong>the</strong><br />

great Indian epic was composed in <strong>the</strong> Himalayan valley in which I live. It is a<br />

book of vast consideration, written in <strong>the</strong> brilliant sunlight of eternally snowcapped<br />

mountains, filled <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> inspiration of clear sparkling waters,<br />

rarefied air <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> life of <strong>the</strong> God-Man – Krishna.<br />

In 1976 I asked Buckminster Fuller, “What should I do <strong>with</strong> my life?”<br />

There seemed <strong>to</strong> be so many roads I could travel <strong>and</strong> I didn’t know which one<br />

<strong>to</strong> choose. Fuller said when he was faced <strong>with</strong> that question, <strong>the</strong> best thing he<br />

95