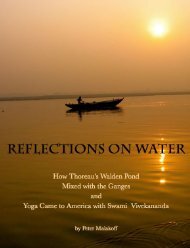

How Thoreau's Walden Pond Mixed with the Ganges and Yoga Came to America with Swami Vivekananda

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century. When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges." This book tells the story of these waters . . .

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.

I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges."

This book tells the story of these waters . . .

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Transcendentalists<br />

“Transcendentalism first arose among New Engl<strong>and</strong> congregationalists, who . . .<br />

rejected predestination, <strong>and</strong> emphasized <strong>the</strong> unity instead of <strong>the</strong> trinity of God .<br />

. . <strong>the</strong> transcendentalists <strong>to</strong>ok <strong>the</strong> stance that empirical proofs of religion were<br />

not possible . . .<br />

The publication of Ralph Waldo Emerson's 1836 essay Nature is usually considered<br />

<strong>the</strong> watershed moment at which transcendentalism became a major cultural<br />

movement. Emerson wrote in his 1837 speech "The <strong>America</strong>n Scholar":<br />

"We will walk on our own feet; we will work <strong>with</strong> our own h<strong>and</strong>s; we will speak<br />

our own minds... A nation of men will for <strong>the</strong> first time exist, because each believes<br />

himself inspired by <strong>the</strong> Divine Soul which also inspires all men." Emerson<br />

closed <strong>the</strong> essay by calling for a revolution in human consciousness <strong>to</strong> emerge<br />

from <strong>the</strong> br<strong>and</strong> new idealist philosophy:<br />

‘So shall we come <strong>to</strong> look at <strong>the</strong> world <strong>with</strong> new eyes. It shall answer <strong>the</strong> endless<br />

inquiry of <strong>the</strong> intellect, — What is truth? <strong>and</strong> of <strong>the</strong> affections, — What is<br />

good? by yielding itself passive <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> educated Will. ...Build, <strong>the</strong>refore, your own<br />

world. As fast as you conform your life <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> pure idea in your mind, that will<br />

unfold its great proportions. A correspondent revolution in things will attend <strong>the</strong><br />

influx of <strong>the</strong> spirit.’. .<br />

Transcendentalists believed that society <strong>and</strong> its institutions—particularly organized<br />

religion <strong>and</strong> political parties—ultimately corrupted <strong>the</strong> purity of <strong>the</strong> individual.<br />

They had faith that people are at <strong>the</strong>ir best when truly "self-reliant"<br />

<strong>and</strong> independent. It is only from such real individuals that true community could<br />

be formed.<br />

Transcendentalism has been influenced by Vedic thought. Thoreau in <strong>Walden</strong><br />

spoke of <strong>the</strong> Transcendentalists' debt <strong>to</strong> Vedic thought directly:<br />

‘In <strong>the</strong> morning I ba<strong>the</strong> my intellect in <strong>the</strong> stupendous <strong>and</strong> cosmogonal philosophy<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Bhagavat Geeta, since whose composition years of <strong>the</strong> gods have<br />

elapsed, <strong>and</strong> in comparison <strong>with</strong> which our modern world <strong>and</strong> its literature seem<br />

puny <strong>and</strong> trivial; <strong>and</strong> I doubt if that philosophy is not <strong>to</strong> be referred <strong>to</strong> a previous<br />

state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down<br />

<strong>the</strong> book <strong>and</strong> go <strong>to</strong> my well for water, <strong>and</strong> lo! <strong>the</strong>re I meet <strong>the</strong> servant of <strong>the</strong><br />

Brahmin, priest of Brahma, <strong>and</strong> Vishnu <strong>and</strong> Indra, who still sits in his temple on<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Ganges</strong> reading <strong>the</strong> Vedas, or dwells at <strong>the</strong> root of a tree <strong>with</strong> his crust <strong>and</strong><br />

water-jug. I meet his servant come <strong>to</strong> draw water for his master, <strong>and</strong> our buckets<br />

as it were grate <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> same well. The pure <strong>Walden</strong> water is mingled<br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> sacred water of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Ganges</strong>.’” . . .<br />

The Transcendental Club<br />

The Transcendental Club was a group of New Engl<strong>and</strong> intellectuals of <strong>the</strong><br />

early-<strong>to</strong>-mid-19th century which gave rise <strong>to</strong> Transcendentalism.<br />

Frederick Henry Hedge, Ralph Waldo Emerson, George Ripley, <strong>and</strong> George<br />

Putnam (1807–1878; <strong>the</strong> Unitarian minister in Roxbury) met in Cambridge,<br />

Massachusetts on September 8, 1836, <strong>to</strong> discuss <strong>the</strong> formation of a new club;<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir first official meeting was held eleven days later at Ripley's house in Bos<strong>to</strong>n.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r members of <strong>the</strong> club included Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson, Theodore<br />

Parker, Henry David Thoreau, William Henry Channing, James Freeman<br />

Clarke, Chris<strong>to</strong>pher Pearse Cranch, Convers Francis, Sylvester Judd, <strong>and</strong> Jones<br />

Very. Female members included Sophia Ripley, Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Peabody,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ellen Sturgis Hooper.<br />

Originally, <strong>the</strong> group went by <strong>the</strong> name "Hedge's Club" because it usually<br />

met when Hedge was visiting from Bangor, Maine. The name Transcendental<br />

Club was given <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> group by <strong>the</strong> public <strong>and</strong> not by its participants. James Elliot<br />

Cabot, a biographer of Emerson, wrote of <strong>the</strong> group as "<strong>the</strong> occasional<br />

meetings of a changing body of liberal thinkers, agreeing in nothing but <strong>the</strong>ir liberality.”<br />

Hedge wrote: "There was no club in <strong>the</strong> strict sense... only occasional<br />

meetings of like-minded men <strong>and</strong> women.” It was sometimes referred <strong>to</strong> by <strong>the</strong><br />

nickname "<strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>rhood of <strong>the</strong> 'Like-Minded'.”<br />

The club was a meeting-place for <strong>the</strong>se young thinkers <strong>and</strong> an organizing<br />

ground for <strong>the</strong>ir idealist frustration <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> general state of <strong>America</strong>n culture<br />

<strong>and</strong> society at <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>and</strong> in particular, <strong>the</strong> state of intellectualism at Harvard<br />

University <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Unitarian church.<br />

– Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia<br />

Related Glossary Terms<br />

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ram Mohun Roy, <strong>Walden</strong> <strong>Pond</strong><br />

Index<br />

Find Term<br />

Section 6 - Introduction<br />

Chapter 2 - The Kashi Yatra, <strong>the</strong> Spiritual Master <strong>and</strong>!<strong>the</strong> Living Water of Life