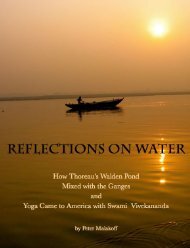

How Thoreau's Walden Pond Mixed with the Ganges and Yoga Came to America with Swami Vivekananda

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century. When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges." This book tells the story of these waters . . .

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.

I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges."

This book tells the story of these waters . . .

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Unitarian<br />

‘We do not hold <strong>the</strong> Bible—or any o<strong>the</strong>r account of human experience—<strong>to</strong><br />

be ei<strong>the</strong>r an infallible guide or <strong>the</strong> exclusive source of truth. Much biblical material<br />

is mythical or legendary. Not that it should be discarded for that reason!<br />

Ra<strong>the</strong>r, it should be treasured for what it is. We believe that we should read <strong>the</strong><br />

Bible as we read o<strong>the</strong>r books—<strong>with</strong> imagination <strong>and</strong> a critical eye. We also respect<br />

<strong>the</strong> sacred literature of o<strong>the</strong>r religions. Contemporary works of science,<br />

art, <strong>and</strong> social commentary are valued as well. We hold, in <strong>the</strong> words of an old<br />

liberal formulation, that "revelation is not sealed." Unitarian Universalists aspire<br />

<strong>to</strong> truth as wide as <strong>the</strong> world—we look <strong>to</strong> find truth anywhere, universally.’<br />

In short, Unitarian Universalists respect <strong>the</strong> important religious texts of o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

religions. UUs believe that all religions can coexist if viewed <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> concept of<br />

love for one's neighbor <strong>and</strong> for oneself. O<strong>the</strong>r church members who do not believe<br />

in a particular text or doctrine are encouraged <strong>to</strong> respect it as a his<strong>to</strong>rically<br />

significant literary work that should be viewed <strong>with</strong> an open mind. It is intended<br />

that in this way, individuals from all religions or spiritual backgrounds could live<br />

peaceably.”<br />

– Our Unitarian Universalist Faith: Frequently Asked Questions, published<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Unitarian Universalist Church<br />

“The following are general tenets of Unitarians:<br />

The universe is a beautiful, intricate, complex place, <strong>the</strong> foundations of which<br />

are a Mystery. The "whole truth" is <strong>to</strong>o large, <strong>and</strong> our minds/knowledge/<br />

intuitions are <strong>to</strong>o small <strong>to</strong> grasp it all. Therefore, we cherish <strong>and</strong> learn from diversity.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> Universe can be said <strong>to</strong> have a purpose, its purpose is for us, not against<br />

us, <strong>and</strong> it is for, not against, us all.<br />

Given how little we can know for sure, our focus should be on this earth <strong>and</strong> life;<br />

beauty, justice, love.<br />

We claim <strong>the</strong> rational, eschew <strong>the</strong> irrational, (contrary <strong>to</strong> reason) <strong>and</strong> question<br />

<strong>the</strong> non-rational (that which is nei<strong>the</strong>r provable nor disprovable by reason alone,<br />

i.e. life after death).<br />

Poetically, this might be stated, "We come from One origin, we are headed <strong>to</strong><br />

One destiny, but we cannot know completely what <strong>the</strong>se are, so we are <strong>to</strong> focus<br />

on making this life better for all of us, <strong>and</strong> we use reason when we can, <strong>to</strong> find<br />

our way.<br />

–Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia