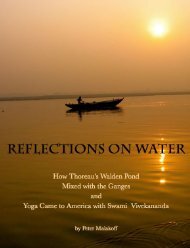

How Thoreau's Walden Pond Mixed with the Ganges and Yoga Came to America with Swami Vivekananda

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century. When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges." This book tells the story of these waters . . .

One early morning in 1846, during the coldest days of a New England winter, Henry David Thoreau looked out the window of his small cabin on Walden Pond and saw men cutting its ice into blocks. That ice was hauled by horse to a railroad that ran across the western edge of Walden Pond, packed into a boxcar, taken to Boston and loaded onto a clipper ship that sailed to Calcutta, India, arriving about four months later. Once there, that ice was purchased by grateful members of the East India Company. Thoreau had witnessed a small part of the global ice trade between New England and India that took place during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

When Thoreau considered the ice trade, his vision sailed on metaphors far beyond the scope of business. The waters he imagined flowed both east and west and carried not just natural elements, but culture, religion and philosophy as well. He envisioned that after arriving in Calcutta, the New England ice of Walden Pond would eventually melt and run downhill where it would join with the sacred water of the Ganges. He wrote in Walden: "It appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and , drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the , since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.

I lay down the book [Bhagavad-Gita] and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of and and who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the , or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges."

This book tells the story of these waters . . .

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Mahendranath Gupta<br />

Mahendranath Gupta (March 12, 1854-June 4,<br />

1932), (also famously known as M <strong>and</strong> Master<br />

Mahashay), was a disciple of Ramakrishna—a<br />

19th-century mystic <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> author of Sri Sri<br />

Ramakrishna Kathamrita, a Bengali classic. He<br />

was also a teacher <strong>to</strong> Paramahansa <strong>Yoga</strong>n<strong>and</strong>a,<br />

a famous 20th century yogi, guru <strong>and</strong> philosopher.<br />

As an adult, Mahendranath, like some of <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r disciples of Ramakrishna, was connected<br />

<strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> Brahmo Samaj for several years. Mahendranath<br />

had lost his mo<strong>the</strong>r at a very early age <strong>and</strong> was experiencing domestic<br />

friction in <strong>the</strong> joint family. As <strong>the</strong> friction <strong>with</strong>in <strong>the</strong> joint family increased,<br />

Mahendranath decided <strong>to</strong> commit suicide. At this critical juncture, Mahendranath's<br />

nephew <strong>to</strong>ok him <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> temple garden of Dakshineswar Kali Temple,<br />

where Ramakrishna, a mystic <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> chief priest of <strong>the</strong> Kali temple lived. It<br />

was here that Gupta met Ramakrishna for <strong>the</strong> first time <strong>and</strong> this meeting was a<br />

turning point in his life. Years later, when Mahendranath was asked about <strong>the</strong><br />

greatest day in his life, he said, "<strong>the</strong> day I had my first darshan of Thakur [Ramakrishna]<br />

in February 1882." According <strong>to</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r traditional accounts, Mahendranath<br />

related that he may have met Ramakrishna for <strong>the</strong> first time when he<br />

was four years old <strong>and</strong> became separated from his mo<strong>the</strong>r while visiting <strong>the</strong> Dakshineswar<br />

Kali Temple. He began crying, <strong>and</strong> a blissful <strong>and</strong> youthful man came<br />

up <strong>and</strong> consoled him. He believed it <strong>to</strong> be Ramakrishna, who was <strong>the</strong>n a priest<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Kali temple.<br />

M had <strong>the</strong> habit of maintaining a personal diary since <strong>the</strong> age of thirteen. M<br />

met Ramakrishna in 1882 <strong>and</strong> attracted by Ramakrishna's teachings, M started<br />

<strong>to</strong> maintain a stenographic record of Ramakrishna's conversations <strong>and</strong> actions<br />

in his diary, which finally <strong>to</strong>ok <strong>the</strong> form of a book Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita.<br />

Initially when M began writing <strong>the</strong> diaries, he had no plans of publication.<br />

Regarding his methodology M wrote,<br />

I wrote everything from memory after I returned home. Sometimes I had <strong>to</strong><br />

keep awake <strong>the</strong> whole night...Sometimes I would keep on writing <strong>the</strong> events of<br />

one sitting for seven days, recollect <strong>the</strong> songs that were sung, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> order in<br />

which <strong>the</strong>y were sung, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> samadhi <strong>and</strong> so on...Many a time I did not feel<br />

satisfied <strong>with</strong> my description of <strong>the</strong> events; I would <strong>the</strong>n immediately plunge myself<br />

in deep meditation ...Then <strong>the</strong> correct image would arise...That is why in<br />

spite of <strong>the</strong> big gap in <strong>the</strong> physical sense, this s<strong>to</strong>ry remains so fresh <strong>and</strong> lifelike<br />

in my mind as if it happened just now.<br />

In each of his Kathamrita entries, M records <strong>the</strong> date, time <strong>and</strong> place of <strong>the</strong><br />

conversation. The title Kathamrita, literally "nectarine words" was inspired by<br />

verse 10.31.9 from <strong>the</strong> Vaishnava text, <strong>the</strong> Bhagavata Purana. Both Ramakrishna's<br />

wife, Sarada Devi, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Swami</strong> Vivekan<strong>and</strong>a later testified <strong>to</strong> Mahendranath's<br />

faithfulness <strong>to</strong> Ramakrishna's words. The first four volumes were published<br />

in 1902, 1904, 1908 <strong>and</strong> 1910 respectively <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> fifth volume in 1932,<br />

delayed because of M's health problems. The Kathamrita contains <strong>the</strong> conversations<br />

of Ramakrishna from 19/26 February 1882 <strong>to</strong> 24 April 1886, during M's<br />

visits. The Kathamrita is regarded as a Bengali classic <strong>and</strong> revered among <strong>the</strong> followers<br />

as a sacred scripture. Famous translations of Kathamrita include works<br />

by <strong>Swami</strong> Nikhilan<strong>and</strong>a(1942), <strong>and</strong> Dharma Pal Gupta.<br />

— Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia