Made in Nigeria

September - Made in Nigeria Edition

September - Made in Nigeria Edition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The Spark | Ignite / Connect / Achieve<br />

www.thesparkng.com<br />

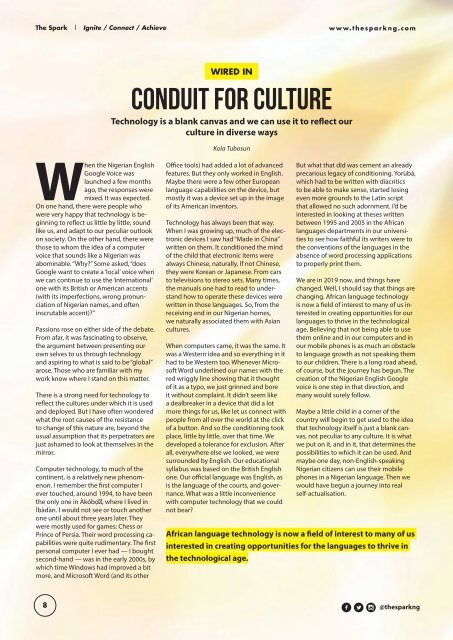

WIRED IN<br />

CONDUIT FOR CULTURE<br />

Technology is a blank canvas and we can use it to reflect our<br />

culture <strong>in</strong> diverse ways<br />

Kola Tubosun<br />

When the <strong>Nigeria</strong>n English<br />

Google Voice was<br />

launched a few months<br />

ago, the responses were<br />

mixed. It was expected.<br />

On one hand, there were people who<br />

were very happy that technology is beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to reflect us little by little, sound<br />

like us, and adapt to our peculiar outlook<br />

on society. On the other hand, there were<br />

those to whom the idea of a computer<br />

voice that sounds like a <strong>Nigeria</strong>n was<br />

abom<strong>in</strong>able. “Why?” Some asked, “does<br />

Google want to create a ‘local’ voice when<br />

we can cont<strong>in</strong>ue to use the ‘<strong>in</strong>ternational’<br />

one with its British or American accents<br />

(with its imperfections, wrong pronunciation<br />

of <strong>Nigeria</strong>n names, and often<br />

<strong>in</strong>scrutable accent)?”<br />

Passions rose on either side of the debate.<br />

From afar, it was fasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g to observe,<br />

the argument between present<strong>in</strong>g our<br />

own selves to us through technology<br />

and aspir<strong>in</strong>g to what is said to be “global”<br />

arose. Those who are familiar with my<br />

work know where I stand on this matter.<br />

There is a strong need for technology to<br />

reflect the cultures under which it is used<br />

and deployed. But I have often wondered<br />

what the root causes of the resistance<br />

to change of this nature are, beyond the<br />

usual assumption that its perpetrators are<br />

just ashamed to look at themselves <strong>in</strong> the<br />

mirror.<br />

Computer technology, to much of the<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ent, is a relatively new phenomenon.<br />

I remember the first computer I<br />

ever touched, around 1994, to have been<br />

the only one <strong>in</strong> Àkóbọ̀, where I lived <strong>in</strong><br />

Ìbàdàn. I would not see or touch another<br />

one until about three years later. They<br />

were mostly used for games: Chess or<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ce of Persia. Their word process<strong>in</strong>g capabilities<br />

were quite rudimentary. The first<br />

personal computer I ever had — I bought<br />

second-hand — was <strong>in</strong> the early 2000s, by<br />

which time W<strong>in</strong>dows had improved a bit<br />

more, and Microsoft Word (and its other<br />

Office tools) had added a lot of advanced<br />

features. But they only worked <strong>in</strong> English.<br />

Maybe there were a few other European<br />

language capabilities on the device, but<br />

mostly it was a device set up <strong>in</strong> the image<br />

of its American <strong>in</strong>ventors.<br />

Technology has always been that way.<br />

When I was grow<strong>in</strong>g up, much of the electronic<br />

devices I saw had “<strong>Made</strong> <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a”<br />

written on them. It conditioned the m<strong>in</strong>d<br />

of the child that electronic items were<br />

always Ch<strong>in</strong>ese, naturally. If not Ch<strong>in</strong>ese,<br />

they were Korean or Japanese. From cars<br />

to televisions to stereo sets. Many times,<br />

the manuals one had to read to understand<br />

how to operate these devices were<br />

written <strong>in</strong> those languages. So, from the<br />

receiv<strong>in</strong>g end <strong>in</strong> our <strong>Nigeria</strong>n homes,<br />

we naturally associated them with Asian<br />

cultures.<br />

When computers came, it was the same. It<br />

was a Western idea and so everyth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> it<br />

had to be Western too. Whenever Microsoft<br />

Word underl<strong>in</strong>ed our names with the<br />

red wriggly l<strong>in</strong>e show<strong>in</strong>g that it thought<br />

of it as a typo, we just gr<strong>in</strong>ned and bore<br />

it without compla<strong>in</strong>t. It didn’t seem like<br />

a dealbreaker <strong>in</strong> a device that did a lot<br />

more th<strong>in</strong>gs for us, like let us connect with<br />

people from all over the world at the click<br />

of a button. And so the condition<strong>in</strong>g took<br />

place, little by little, over that time. We<br />

developed a tolerance for exclusion. After<br />

all, everywhere else we looked, we were<br />

surrounded by English. Our educational<br />

syllabus was based on the British English<br />

one. Our official language was English, as<br />

is the language of the courts, and governance.<br />

What was a little <strong>in</strong>convenience<br />

with computer technology that we could<br />

not bear?<br />

But what that did was cement an already<br />

precarious legacy of condition<strong>in</strong>g. Yorùbá,<br />

which had to be written with diacritics<br />

to be able to make sense, started los<strong>in</strong>g<br />

even more grounds to the Lat<strong>in</strong> script<br />

that allowed no such adornment. I’d be<br />

<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g at theses written<br />

between 1995 and 2005 <strong>in</strong> the African<br />

languages departments <strong>in</strong> our universities<br />

to see how faithful its writers were to<br />

the conventions of the languages <strong>in</strong> the<br />

absence of word process<strong>in</strong>g applications<br />

to properly pr<strong>in</strong>t them.<br />

We are <strong>in</strong> 2019 now, and th<strong>in</strong>gs have<br />

changed. Well, I should say that th<strong>in</strong>gs are<br />

chang<strong>in</strong>g. African language technology<br />

is now a field of <strong>in</strong>terest to many of us <strong>in</strong>terested<br />

<strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g opportunities for our<br />

languages to thrive <strong>in</strong> the technological<br />

age. Believ<strong>in</strong>g that not be<strong>in</strong>g able to use<br />

them onl<strong>in</strong>e and <strong>in</strong> our computers and <strong>in</strong><br />

our mobile phones is as much an obstacle<br />

to language growth as not speak<strong>in</strong>g them<br />

to our children. There is a long road ahead,<br />

of course, but the journey has begun. The<br />

creation of the <strong>Nigeria</strong>n English Google<br />

voice is one step <strong>in</strong> that direction, and<br />

many would surely follow.<br />

Maybe a little child <strong>in</strong> a corner of the<br />

country will beg<strong>in</strong> to get used to the idea<br />

that technology itself is just a blank canvas,<br />

not peculiar to any culture. It is what<br />

we put on it, and <strong>in</strong> it, that determ<strong>in</strong>es the<br />

possibilities to which it can be used. And<br />

maybe one day, non-English-speak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>Nigeria</strong>n citizens can use their mobile<br />

phones <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Nigeria</strong>n language. Then we<br />

would have begun a journey <strong>in</strong>to real<br />

self-actualisation.<br />

African language technology is now a field of <strong>in</strong>terest to many of us<br />

<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g opportunities for the languages to thrive <strong>in</strong><br />

the technological age.<br />

8<br />

fli @thesparkng