Africa's Visual Vernacular by Uche Okpa-Iroha

From Spring 2020 special Africa issue of ZEKE magazine

From Spring 2020 special Africa issue of ZEKE magazine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

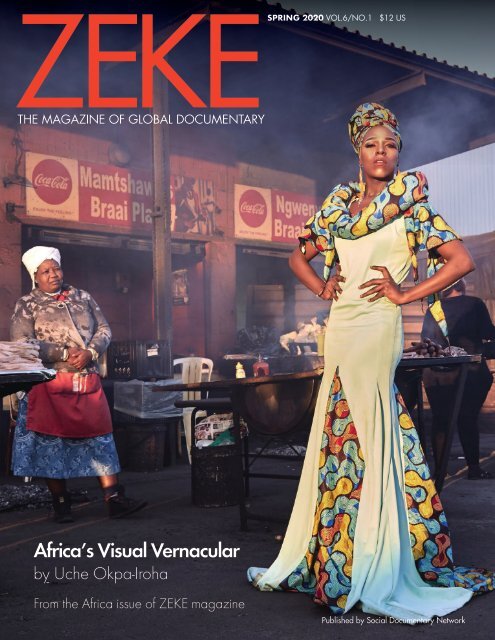

ZEKE<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF GLOBAL DOCUMENTARY<br />

SPRING 2020 VOL.6/NO.1 $12 US<br />

Africa’s <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Vernacular</strong><br />

<strong>by</strong> <strong>Uche</strong> <strong>Okpa</strong>-<strong>Iroha</strong><br />

From the Africa issue of ZEKE magazine<br />

Published <strong>by</strong> Social Documentary Network

Africa’s <strong>Visual</strong> <strong>Vernacular</strong><br />

.......................................................<br />

By <strong>Uche</strong> <strong>Okpa</strong>-<strong>Iroha</strong><br />

The practice of photography in<br />

Africa is as old as its introduction<br />

to the world <strong>by</strong> Francois<br />

Arago in 1839 in France. Today<br />

it has become the ‘go-to’ technology<br />

through which the world<br />

seeks to narrate and explain<br />

events irrespective of the context.<br />

Photography, then, in its infancy was<br />

regarded with a fair dose of suspicion<br />

with skeptics questioning its role and<br />

motives.<br />

As photography was being unveiled<br />

in France, purveyors and colonists were<br />

already on their way to the Continent<br />

in search of ‘treasure.’ Inevitably the<br />

camera became part of the lingua franca<br />

and Africa, a stage where every other<br />

form of expression that was antithetical<br />

to its existence (be it cultural, economic,<br />

political or social) was experimented.<br />

The Continent had little or no say in<br />

molding her image or visual narrative<br />

during the colonial era. This narrative<br />

has persisted for over 150 years and<br />

has become embedded in the modern<br />

psyche of western countries. It supports<br />

the portrayal of the Continent as a land<br />

in perpetual struggle. However this narrative<br />

has in recent years been questioned<br />

<strong>by</strong> African artists who in the mid-20 th<br />

century emerged as proponents of subversion<br />

to challenge the age-old western<br />

accounts and its consequential parochial<br />

representations of the Continent.<br />

Modern and contemporary history<br />

has often seen western writers present<br />

Africa in a poor light and the context<br />

skewed so as to titillate or entrench<br />

already held misconceptions of the<br />

Continent <strong>by</strong> the home audience.<br />

Often topics relating to the Continent’s<br />

political, social or cultural essence, are<br />

highlighted with the usual stereotypical<br />

reference to poverty, diseases or political<br />

2 / ZEKE SPRING 2020<br />

instability, there<strong>by</strong> relegating innovative<br />

agendas and policies <strong>by</strong> African states<br />

from the mainstream of international<br />

discourse. For decades, this image of<br />

Africa has been held as the official narrative<br />

that is accepted, especially in the<br />

west. Despite the gains and successes<br />

of the 54 countries that constitute this<br />

richly endowed continent, a Euro-centric<br />

vernacular has continuously coalesced<br />

into clichés, representations and myths<br />

often known as the ‘master’ narrative.<br />

This essay is not aimed at highlighting<br />

western parochialism towards Africa but<br />

hopes to analyze the diverse narratives<br />

of the Continent in relation to photography<br />

and the role of the medium in<br />

present day Africa.<br />

Ideological Influence of<br />

Colonialism<br />

From the onset, African practitioners<br />

have been keen observers of their<br />

environment despite the unquestionable<br />

influence of Europeans who<br />

introduced photography at the same<br />

time as colonialism. In as much as it<br />

was a given that the colonists —comprising<br />

of missionaries, merchants and<br />

adventurers—profited from the creation<br />

of these images, little or no questions<br />

were asked if they reflected the reality<br />

on the ground. From early to mid-19th<br />

century, African photographers began to<br />

collaborate with their European counterparts<br />

in creating images that reflected<br />

their vernacular. No doubt, most of them<br />

were apprentices or worked directly to<br />

the dictates of the colonial administrators<br />

and missionaries. And despite the<br />

ideological influence of colonialism and<br />

its excessive control, the early African<br />

photographers began to gradually<br />

redefine the Continent’s new image<br />

from a domestic perspective. I am of<br />

the opinion that colonial tutelage and<br />

its effect on early African practitioners<br />

played a significant role in shaping the<br />

visual myths that are perceptible today.<br />

The focus during the 19th century fell<br />

within the boundaries of anthropology<br />

and ethnography — the earliest noticeable<br />

language of photography in Africa<br />

at the time.<br />

In West Africa in the mid to the late<br />

19th century, a group of young and<br />

enterprising photographers led the<br />

movement and produced some relevant<br />

and outstanding works. Notable photographers<br />

such as the African American<br />

Augustus Washington, who was disenchanted<br />

<strong>by</strong> black subjugation in America<br />

in the 1850s, moved to Liberia and later<br />

established studios in Sierra Leone, the<br />

Gambia, and Senegal. 1 There was also<br />

the very itinerant Francis Wilberforce<br />

Joaque, who was educated in the<br />

Grammar School in Freetown run <strong>by</strong> the<br />

Church Missionary Society (CMS). 2 In the<br />

1860s, he moved to Fernando Po (present<br />

day Equatorial Guinea) where he<br />

pioneered and practiced photography. 3<br />

As the 19 th century drew to a close,<br />

photography had already become an<br />

important visual form of expression in<br />

Africa. More entrepreneurs came into<br />

the field in the central and the southern<br />

parts of the Continent. New visual<br />

dialects and provincialism began to<br />

emanate from the defined borders of<br />

anthropology and ethnography away<br />

from the influence of the European perspective<br />

which was still relevant in the<br />

context of African photography at that<br />

time. There were conscientious photographers<br />

who also photographed events<br />

independently in their regions. Today,<br />

the works of Jonathan Adagogo Green

...<br />

and Hezekiah Andrew Shanu remain<br />

vital in the study of colonial imperialism<br />

in the Niger Delta and in Boma in the<br />

Congo Free State. It was Green who in<br />

1897 photographed the deposed Oba<br />

Ovonramwen of Benin and his family on<br />

board the ship SS Ivy on his way to exile<br />

in Calabar. Green, who (it is believed)<br />

had been trained in Europe, photographed<br />

the evolving state of colonialism<br />

and societal change in southeastern<br />

Nigeria. His photographs depict native<br />

Bonny aristocracy and their families in<br />

vernacular settings. Shanu had a studio<br />

opened in Boma from where he had<br />

access to the atrocious events in the<br />

Congo Free State. He is credited with<br />

playing an important role in providing<br />

photographic evidence of the atrocities<br />

suffered under King Leopold’s regime in<br />

Congo. 4<br />

A New Generation of<br />

Photographers<br />

The viewpoint on the subcontinent<br />

introduced through colonist ideologies<br />

began to manifest the bi-polar nature of<br />

photography — the real and the myth in<br />

the works of individuals like Jules Leger,<br />

William Ring, Carel Sparemann, William<br />

Walter and John Paul between 1840 and<br />

1855. Their approach was similar to their<br />

contemporaries in West and East Africa.<br />

The photographs covered local sceneries,<br />

colonial officers, and portraits of notables<br />

within the administrative, social and<br />

cultural classes. To the east, the Swahili<br />

shores adjacent to the Indian Ocean<br />

attracted a lot of interest from purveyors<br />

and photographers alike in the early 20 th<br />

century. The topographical richness of the<br />

region and its cultural diversity with people<br />

from Asia, Middle East, Europe and<br />

Africa gave the major cities in Tanzania,<br />

Kenya and Uganda colorful, enchanting<br />

and picturesque credentials. The Omani<br />

empire was at its twilight during this<br />

period (the early 20 th century) but the<br />

appeal of royalty brought its measure of<br />

exoticism with opulent palaces, exquisite<br />

fashion and lush landscapes. This element<br />

was the focus for early 20 th century photographers<br />

like J.B Coutinho, C. Vincenti,<br />

Frank & Frances Carpenter and Eric<br />

Photograph <strong>by</strong> Zanele Muholi. Somnyama in Lafayette, New York, 2016. © Zanele<br />

Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, NY.<br />

The Prince Claus award recipient and one<br />

of South Africa’s leading photographers,<br />

Zanele Muholi, is as assertive as she is<br />

intriguing. She has exhibited her work in<br />

prominent galleries, museums and festivals<br />

all over the world.<br />

Her portfolio focuses intensely on<br />

marginalized communities (such as the LGBT)<br />

in South Africa and in her travels who often<br />

have limited involvement in mainstream<br />

political, economic, cultural and social<br />

activities due to their conditions, lifestyles or<br />

exclusion.<br />

A common theme in her work is her direct<br />

involvement in interrogating her subject<br />

matter <strong>by</strong> means of identification through<br />

association, dress codes, and viewpoints.<br />

Matson. The cities of Mombassa, Dar es<br />

Salaam, Nairobi, and Blantyre provided<br />

residence for a group of photographers<br />

who were particular about photographing<br />

commercial activities, Arab architecture,<br />

Muholi’s thought-provoking work Somnyama<br />

Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness takes a<br />

look at the politics of identity and representation<br />

through the gaze of anthropology and<br />

ethnography. Her narrative and classification<br />

of society become apparent in her use<br />

of the terms ‘they’, ‘them’, and ‘other’. The<br />

potency and visual impact of the work is<br />

proved <strong>by</strong> the deliberate and effective use of<br />

props. And her excessively darkened body<br />

is a platform for resistance and campaign<br />

against prejudice and parochial perceptions.<br />

Muholi’s ebony skin projects a message<br />

of defiance and assertiveness drawing the<br />

viewer into her realm to understand the<br />

message and to decode the meaning for<br />

themselves.<br />

tribal people (considered as exotic) and<br />

the day to day life of the upper class.<br />

The emergence of this new generation<br />

of photographers in the 21 st century can<br />

be attributed to their orientation to local

Photograph <strong>by</strong> George Osodi. A woman drying tapioca a casava cake near a gas flare while her child tries to protect a little ba<strong>by</strong> on her back from heat from the flare in<br />

Utorogun Niger Delta, Nigeria, November 2006.<br />

and international festivals, biennials and<br />

exchange programs as well as informal<br />

platforms that offer photography schooling.<br />

There are few other instances that<br />

have instigated the awakening of interest<br />

in the field of photography, contributing<br />

to its development and evolution into<br />

diverse vernaculars of visual expression<br />

in contemporary time. I will examine a<br />

few milestones and practitioners who<br />

heralded the growth of the medium in<br />

Africa.<br />

The Language of Resistance<br />

Before the apartheid regime came to<br />

an end in South Africa in 1994, an<br />

important movement in photography<br />

had begun in 1989 under the auspices<br />

of renowned photographer David<br />

Goldblatt. This platform took into cognizance<br />

the exclusion and marginalization<br />

of black communities as the country<br />

looked to the future with hope for a new<br />

nation. The Market Photo Workshop is<br />

an organization that offers a dynamic<br />

visual pedagogy for the training of<br />

photographers with emphasis on the<br />

pre and post-apartheid experiences of a<br />

country and its people.<br />

A close examination of the portfolios<br />

of relevant photographers from<br />

South Africa reveals a partisanship and<br />

consistency in language. The emotional,<br />

psychological, sociological and cultural<br />

sensibilities of the South African<br />

environment are evidently imprinted in<br />

the notable oeuvres from Ernest Cole,<br />

Peter Magubane, Santu Mofokeng,<br />

Cedric Nunn to Zanele Muholi, Andrew<br />

Tshanbangu, Jo Ractliffe, Jodi Bieber,<br />

Sabelo Mlangeni, among others. Though<br />

the individuality of each photographer<br />

distinguishes their thoughts and production<br />

processes, they all have one common<br />

denominator engrained in them: the<br />

language of resistance and protest but in<br />

subtle annunciations. Unlike the pioneers<br />

of photography in Africa, this generation<br />

owned their voices and they remained<br />

unrestrained. The influence is obvious<br />

with the works of Musa Nxumalo and<br />

Lebohang Kgange whose works delve<br />

into personal lives both of themselves<br />

and their families thus showcasing<br />

bonds of association, love, friendship<br />

and community with observed social<br />

protocols that are apparent in South<br />

Africa and especially in Johannesburg.<br />

The Bamako Encounters established<br />

in 1994 is Africa’s preeminent biennial<br />

for photography and has been a major<br />

catalyst for the promotion of emerging<br />

photographers since inception. Today,<br />

with its reach, message and context,<br />

we have seen the likes of Pieter Hugo<br />

(South Africa), Baudouin Mouanda (DR<br />

Congo), Zanele Muholi (South Africa),<br />

Rana El Nemr (Egypt), Mamadou Konate<br />

(Mali),Omar Victor Diop (Senegal),<br />

Fatoumata Diabate (Mali), Emeka<br />

Okereke (Nigeria), Nyani Quarmyne<br />

(Ghana), Malala Andrialavidrazana<br />

(Madagascar), <strong>Uche</strong>chukwu James <strong>Iroha</strong><br />

(Nigeria), Zohra Bensemra (Algeria) and<br />

others make great strides and take their<br />

rightful place on the international photography<br />

circuit. They are the reinvigorated<br />

voice of Africa with fresh perspective on<br />

global events. And the relevance of the<br />

biennials like the festivals in Bamako,<br />

4 / ZEKE SPRING 2020

Photograph <strong>by</strong> Andrew Esiebo<br />

Lagos, Addis Ababa, is the projection of<br />

Africa’s cultural heritage as a diverse and<br />

inexhaustible resource. This diversity can<br />

become a key instrument in the development<br />

of Africa’s visual vernacular in all<br />

manner of artistic and visual representations<br />

(in films, videos, photography and<br />

new media) supported with new philosophies,<br />

ideologies and knowledge.<br />

Nigeria’s <strong>Visual</strong> Language<br />

There are elements that have become<br />

distinctive to different regions of Africa<br />

and have seamlessly been diffused into<br />

artistic productions. A typical marker of<br />

this is Nigeria, a country of about 200<br />

million people with almost 500 tribal<br />

languages. Nigeria is considered to be<br />

a major player in the global art scene<br />

and especially in photography. Lagos is<br />

the creative powerhouse in Nigeria — a<br />

mega city of about 25 million people<br />

and as diverse and complex as the<br />

country itself.<br />

Language and culture is often used<br />

to define a people and Nigeria’s visual<br />

language can be explained as an<br />

aggregation of its ethnic and cultural<br />

stakeholders, their relationships and<br />

interdependence and a shared history<br />

of photography since the arrival of the<br />

first Europeans. As the medium evolved<br />

over time, Nigeria’s provincialism has<br />

become more pronounced. In Rotimi<br />

Fani-Kayode’s work “body” we see the<br />

collision of subjectivity and materiality.<br />

The exuberance of sensuality and<br />

spirituality become the focal point in his<br />

discourse on religion and social codes.<br />

He explores identity (the freedom of the<br />

body) and politics and the relationship<br />

between the former and photography.<br />

The works of younger photographers<br />

like George Osodi, Andrew Esiebo,<br />

Abraham Oghobase, Adeola Olagunju<br />

and Etinosa Yvonne Osayimwen share<br />

similar traits and ratify the diverse dialects<br />

that define the practice in Nigeria.<br />

George Osodi brings a diverse and<br />

complex insight to Nigerian photography<br />

through his journalistic inclinations.<br />

Through his work “eyes,” the world<br />

became aware of the insurgent/militant<br />

activities in the Niger Delta of Nigeria<br />

(2003–2013). His politically charged<br />

photographs raised questions of neglect,<br />

corruption and tribe-ethnic leanings in<br />

the bureaucratic corridors of power in<br />

Nigeria. In other projects, his versatility is<br />

buttressed and he takes different tangents<br />

to engage in other realms like culture with<br />

his work “Nigerian Monarchs” (2011–<br />

present), a study on the custodians of<br />

royal traditional stools and their roles in<br />

Nigerian society and politics. He investigates<br />

the bustling metropolis of Lagos<br />

with an in-depth study of its inhabitants,<br />

streets, traffic and nightlife and tries to<br />

make sense of the abundant contradictions<br />

and peculiarities. The revelations<br />

of the idiosyncratic nature of Lagos are<br />

evident in his “Lagos Uncelebrated”<br />

project (2007–2013). Osodi’s oeuvres<br />

represent visual provincialisms which are<br />

polyphonic and pluralistic.<br />

Corroborating Osodi’s eclectic<br />

approach is the energetic and prolific<br />

Nigerian photographer Andrew Esiebo.<br />

Both have similar traits with works that<br />

are visually partisan. Ideologically, they<br />

ZEKE SPRING 2020/ 5

share the same views and tend to reimage<br />

and re-imagine their spaces along<br />

similar itinerant perspectives. Esiebo’s<br />

works are conduits for the expression of<br />

his diverse visions, ideas and thoughts.<br />

He often approaches his subject from a<br />

journalistic standpoint. Esiebo covers a<br />

wide range of topical issues like spirituality<br />

or religion in “God is Alive” (2006<br />

– present), gender and homosexuality<br />

“Who We Are” (2007– 2010), sports/<br />

football “Love It” (2006) and lifestyle<br />

“Pride” (2012). Esiebo and Osodi<br />

share similarities and influences which<br />

suggest a possible cross-fertilization of<br />

ideas and philosophies in their formative<br />

years. Esiebo’s unique photographs are<br />

a clear deviation of the clichéd anecdotes<br />

and narratives of western gaze on<br />

Africa. Clearly, his photographs are very<br />

independent of any outside influences or<br />

control as he is conscientious in reporting<br />

events around him.<br />

Another contemporary Nigerian photographer<br />

is Abraham Oghobase (winner<br />

of the Prix Okwui Enwezor at the 12 th<br />

Bamako Encounter in 2019). Oghobase<br />

is known for his reactive photography.<br />

He explores the relationship between his<br />

emotions, that of his subjects, and the<br />

spaces of his encounters. His work delves<br />

into the territories of conceptual photography<br />

with primary focus on experimentation,<br />

research, and materiality and lived<br />

experiences. He sees his body as a blank<br />

canvas upon which his narratives can<br />

be superimposed. An avid self-portraitist,<br />

Oghobase has a well-defined position<br />

and voice in Nigerian and African<br />

photography. His style of work and rich<br />

portfolio has influenced young female<br />

photographers like Adeola Olagunju and<br />

Etinosa Yvonne Osayimwen.<br />

Adeola Olagunju, a recent winner of<br />

the Grand Prix Seydou Keita award at<br />

the 12th Bamako Encounters (2019) and<br />

an alumnae of the Nlele Institute Lagos,<br />

also uses her body like Oghobase as the<br />

subject. Olagunju focuses on memory,<br />

vulnerability, experiences and emotions.<br />

In her recent work “Home Is” (2019),<br />

she is seen together with a model in a<br />

staged project with a vibrant background<br />

accentuated with textures and layers. The<br />

colors, lines and textures are metaphors<br />

which reflect the emotional state of her<br />

mind as she ventures to conceptualize the<br />

process of homemaking and the intricacies<br />

that are evident in relationships<br />

between spouses. The work is subtle and<br />

addresses the performativity in photography<br />

also seen in Abraham Oghobase’s<br />

work. Her award winning projects in<br />

Bamako “Transmutations” (2019) and<br />

“Pilgrimage” (2018) use both photography<br />

and video. A new dimension and<br />

approach exists now among contemporary<br />

photographers of African descent<br />

who challenge limitations and stereotypes<br />

there<strong>by</strong> finding avenues through diverse<br />

languages or media to engage with their<br />

audience. Olagunju’s work in Bamako<br />

(2019) had all the attributes of double<br />

exposure photography where layers of<br />

screens used in the presentation form or<br />

serve as recurrent metaphors.<br />

East Africa’s Optimism<br />

Similarly in East Africa, we see the<br />

excitement and vibrancy of colors in the<br />

portraits of renowned Ethiopian photographer<br />

Aida Muluneh. Muluneh is the<br />

founder of Defta for Africa (DFA) and the<br />

Addis Foto Fest. Muluneh’s work gives<br />

a fairytale insight into the beauty and<br />

lifestyle of African women through her<br />

rich color portraitures. She is constantly<br />

involved in introspection, questioning her<br />

work and herself and trying to find new<br />

perspectives to explain her philosophy.<br />

In her recent project, “The Memory of<br />

Hope” (2017), Muluneh integrates the<br />

optimism which she believes shaped<br />

her upbringing, youth and indeed her<br />

life. She is also particular about western<br />

stereotypes within the confines of gender<br />

representation and identity. Muluneh<br />

uses or places her models in the conventional<br />

portrait layout, and mostly<br />

explores the subject like a performance.<br />

Photograph <strong>by</strong> Abraham Oghobase<br />

6 / ZEKE SPRING 2020

Notes:<br />

1<br />

Jurg Schneider, Portrait Photography: <strong>Visual</strong><br />

Currency in the Atlantic <strong>Visual</strong> scape. Portraiture<br />

& Photography in Africa, Pg 40, 2013<br />

2<br />

Jurg Schneider, Portrait Photography: <strong>Visual</strong><br />

Currency in the Atlantic <strong>Visual</strong> scape. Portraiture<br />

& Photography in Africa, Pg 46, 2013<br />

3<br />

Jurg Schneider, Portrait Photography: <strong>Visual</strong><br />

Currency in the Atlantic <strong>Visual</strong> scape. Portraiture<br />

& Photography in Africa, Pg 40, 2013<br />

4<br />

Erin Haney, “Fools Eye: Innocent Photographs”,<br />

Omenka magazine, Pg 81, Volume 1, Issue 2,<br />

2013<br />

Photograph <strong>by</strong> Adeola Olagunju<br />

Repositioning the Continent<br />

In recent years, photography in Africa<br />

has become a huge enterprise and<br />

movement. Photographers in Africa are<br />

more or less concerned with mounting<br />

new vistas in an effort to reposition their<br />

continent as the next frontier of possibilities,<br />

hence creating new knowledge,<br />

breaking down monopolies and opining<br />

directly how Africa is perceived.<br />

I will sum up this essay with the work<br />

of Senegalese photographer Omar<br />

Victor Diop as corollary to the vibrant<br />

work of Aida Muluneh. Diop’s work is<br />

allegorical, captivating and emotional<br />

with distinctive historical narrative. His<br />

projects including “Liberty”, “Diaspora”,<br />

“The Studio of Vanities”, “(Re-) Mixing<br />

Hollywood”, and others all resonate<br />

with a strong African theme. The likes<br />

of JA Green, Malick Sidibe, Seydou<br />

Keita, JD Okhai’ Ojeikere, Ricardo<br />

Rangel, David Goldblatt and others<br />

have all influenced his work in one way<br />

or another. Like Diop, other exciting<br />

photographers are coming to the fore<br />

with notable impact on the African<br />

photography scene. The likes of Mario<br />

Macilau (Mozambique), Mauro Pinto<br />

(Mozambique), Simon Gush (South<br />

Africa), George Sanga (DR Congo),<br />

Em’kal Eyongakpa (Cameroon), Malala<br />

Andrialavidrazana (Madagascar),<br />

<strong>Uche</strong>chukwu James-<strong>Iroha</strong> (Nigeria),<br />

Oumou Diarra (Mali), Nyani Quarmyne<br />

(Ghana), Nyaba Leon Ouedrago (Cote<br />

d’ Ivoire) and others will continue<br />

(through their works) to redefine Africa<br />

with regard to contextualization and<br />

perception.<br />

As we gaze into the future, these<br />

stakeholders will continue to reinvent and<br />

reinvigorate the Continent through the<br />

rich diversity of their visual dialects, thus<br />

creating layers of African narratives that<br />

are firmly embedded in proud partisanships<br />

and provincialisms.<br />

Photograph <strong>by</strong> Aida Muluneh<br />

ZEKE SPRING 2020/ 7

Three Ways to Access ZEKE<br />

• Subscribe: $21.00* for two issues/year<br />

• Individual copy: $13.00*<br />

• Digital access: $3.50<br />

* Additional costs for shipping to addresses outside the US.<br />

Click here to find out how »