The American Philatelist May 2018

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

pathfinder planes checking the route, so he wasn’t transporting<br />

mail. Todd had lunch in Bellefonte and left for Cleveland<br />

that afternoon.<br />

Also on the afternoon of the December 17, another Army<br />

flying instructor, Edward A. “Al” Johnson, landed at Beaver<br />

Airfield. Johnson stayed overnight and left at 9 a.m. on December<br />

18, with one sack of mail for Cleveland only. Johnson<br />

seems to have been the intended relay pilot/plane meeting<br />

Smith, but news reports say he became impatient when<br />

Smith was late in arriving at Bellefonte, and left.<br />

Smith, arriving in Bellefonte around 11:15 a.m. December<br />

18, had no choice but to fly on to Cleveland himself. He<br />

had a map only for the route from New York to Bellefonte, so<br />

a man at the airfield provided a makeshift map of the route<br />

to Cleveland.<br />

Despite having the appropriate map, Johnson got lost and<br />

flew past Cleveland, landing in Sandusky, Ohio, and his sack<br />

of mail for Cleveland traveled from Sandusky by automobile<br />

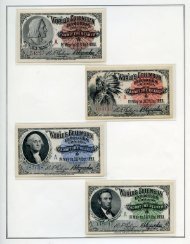

or train. <strong>The</strong> Cleveland mail that Johnson was carrying had a<br />

Bellefonte cancel and then a Cleveland backstamp, as shown<br />

on the special delivery cover illustrated here.<br />

So, there were two opportunities for flown covers from<br />

Bellefonte on December 18, 1918 carried by Edward Johnson<br />

or Leon Smith.<br />

Reminiscences of the Early Days<br />

<strong>The</strong> airfield in Bellefonte was in use only until flying mail<br />

by night became possible. <strong>The</strong> original field was too small<br />

for the larger planes and all the lighting necessary for night<br />

flights. A spacious new airfield was constructed in nearby<br />

Pleasant Gap and the first night landing took place on July<br />

1, 1925. While the airfield was right in their neighborhood,<br />

however, Bellefonte residents reveled in the excitement, and<br />

welcomed the young men (sometimes only 19 or 20 years<br />

old) into their homes and daily lives. <strong>The</strong> pilots dated local<br />

young women and joined their circles of friends, played golf<br />

at local courses and on town baseball teams, and celebrated<br />

their birthdays in the company of new acquaintances.<br />

Interviewed in 1991 for an article in Air & Space magazine,<br />

local historian (and now the late) Hugh Manchester recalled<br />

that, “<strong>The</strong>re was an intimacy between the pilots and<br />

the town. If they spotted a fire they’d<br />

buzz the house to make sure people<br />

452 AMERICAN PHILATELIST / MAY <strong>2018</strong><br />

$ $<br />

were awake. <strong>The</strong>y were heroes to the kids, girls as well as<br />

boys. ... I suppose the airmail years were like the Golden Age<br />

of Greece for us.”<br />

When pilots began dying in the line of duty, beginning<br />

with Charles H. Lamborn on July 19, 1919, just after flying<br />

out of the Bellefonte airfield, it was not just news, but a personal<br />

loss. <strong>The</strong> Democratic Watchman noted, “As a man he<br />

was a very likable fellow; clean cut, straightforward, unobtrusive.<br />

His short residence in Bellefonte won for him the esteem<br />

and friendship of a large circle of acquaintances who were<br />

shocked at his sad end almost as though he had been a lifelong<br />

friend.” Nine pilots died in 1920, including some of the<br />

most admired local fliers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> mail pilots themselves called their group “the suicide<br />

club.” Jack Knight, hero of the night mail and long experienced<br />

on the eastern route, noted in his log of November 21,<br />

1920, “Cleveland to Bellefonte, Fog – Wrote my will.” In Liberty<br />

magazine, August 11, 1928, Paul Collins, then a veteran<br />

of some 500,000 miles in the mail service, recalled his first<br />

flight, seven and a half years earlier. He was trailed from the<br />

airfield by a small boy who asked, “Say, mister, what does it<br />

feel like to be a regular mail pilot?” Collins replied, “Son, it<br />

felt to me like a terrible accident looking for someplace to<br />

happen.”<br />

Pioneers Paid Steep Price<br />

<strong>The</strong> accidents, especially in the early years of the airmail<br />

service, were reported in detail in the national press, offering<br />

great scope to more imaginative and lurid writers. <strong>The</strong><br />

airmail route through Pennsylvania came to be called “Hell’s<br />

Stretch, “Hell Stretch,” “Devil Stretch,” “Graveyard of the<br />

Aviators,” “Graveyard of the Alleghenies,” and “Graveyard of<br />

Aviation.” <strong>The</strong> graveyard names seem to have originated with<br />

coverage of the fatal crash of Charles Ames on October 1,<br />

1925 near Bellefonte. Ames and his plane were the focus of a<br />

10-day search that received national attention.<br />

Ames was the 30th airmail pilot to die since the Post Office<br />

Department took over the service in 1918. However, he<br />

was only the fifth (and the last) mail pilot to die in Pennsylvania<br />

in the governmental airmail period, 1918-1927.<br />

<strong>The</strong> National Postal Museum lists 35 pilot deaths during the<br />

CONFEDERATE STAMPS AND POSTAL HISTORY<br />

$ PATRICIA A. KAUFMANN<br />

10194 N. OLD STATE ROAD • LINCOLN, DE 19960<br />

CALL: 302-422-2656 • FAX: 302-424-1990<br />

$<br />

TRISHKAUF@COMCAST.NET<br />

$<br />

PROFESSIONAL PHILATELIST SINCE 1973<br />

LIFE MEMBER: CSA, APS, APRL, USPCS<br />

MEMBER: ASDA, CCNY, RPSL<br />

EXTENSIVE RETAIL STOCK ONLINE<br />

$<br />

www.trishkaufmann.com $ $