CM September 2021

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

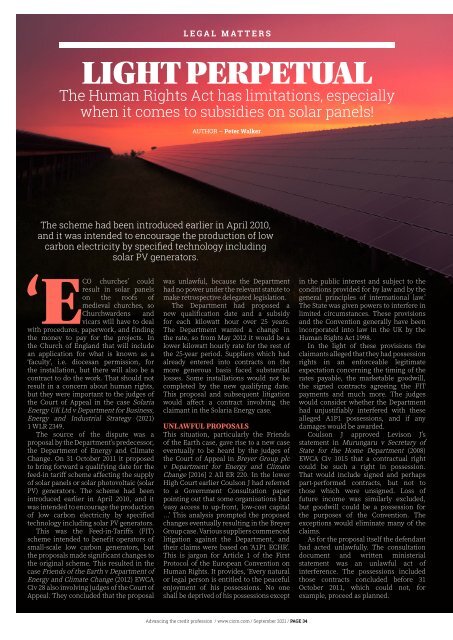

LEGAL MATTERS<br />

LIGHT PERPETUAL<br />

The Human Rights Act has limitations, especially<br />

when it comes to subsidies on solar panels!<br />

AUTHOR – Peter Walker<br />

The scheme had been introduced earlier in April 2010,<br />

and it was intended to encourage the production of low<br />

carbon electricity by specified technology including<br />

solar PV generators.<br />

churches’ could<br />

result in solar panels<br />

on the roofs of<br />

medieval churches, so<br />

Churchwardens and<br />

‘ECO<br />

vicars will have to deal<br />

with procedures, paperwork, and finding<br />

the money to pay for the projects. In<br />

the Church of England that will include<br />

an application for what is known as a<br />

‘faculty’, i.e. diocesan permission, for<br />

the installation, but there will also be a<br />

contract to do the work. That should not<br />

result in a concern about human rights,<br />

but they were important to the judges of<br />

the Court of Appeal in the case Solaria<br />

Energy UK Ltd v Department for Business,<br />

Energy and Industrial Strategy (<strong>2021</strong>)<br />

1 WLR 2349.<br />

The source of the dispute was a<br />

proposal by the Department’s predecessor,<br />

the Department of Energy and Climate<br />

Change. On 31 October 2011 it proposed<br />

to bring forward a qualifying date for the<br />

feed-in tariff scheme affecting the supply<br />

of solar panels or solar photovoltaic (solar<br />

PV) generators. The scheme had been<br />

introduced earlier in April 2010, and it<br />

was intended to encourage the production<br />

of low carbon electricity by specified<br />

technology including solar PV generators.<br />

This was the Feed-in-Tariffs (FIT)<br />

scheme intended to benefit operators of<br />

small-scale low carbon generators, but<br />

the proposals made significant changes to<br />

the original scheme. This resulted in the<br />

case Friends of the Earth v Department of<br />

Energy and Climate Change (2012) EWCA<br />

Civ 28 also involving judges of the Court of<br />

Appeal. They concluded that the proposal<br />

was unlawful, because the Department<br />

had no power under the relevant statute to<br />

make retrospective delegated legislation.<br />

The Department had proposed a<br />

new qualification date and a subsidy<br />

for each kilowatt hour over 25 years.<br />

The Department wanted a change in<br />

the rate, so from May 2012 it would be a<br />

lower kilowatt hourly rate for the rest of<br />

the 25-year period. Suppliers which had<br />

already entered into contracts on the<br />

more generous basis faced substantial<br />

losses. Some installations would not be<br />

completed by the new qualifying date.<br />

This proposal and subsequent litigation<br />

would affect a contract involving the<br />

claimant in the Solaria Energy case.<br />

UNLAWFUL PROPOSALS<br />

This situation, particularly the Friends<br />

of the Earth case, gave rise to a new case<br />

eventually to be heard by the judges of<br />

the Court of Appeal in Breyer Group plc<br />

v Department for Energy and Climate<br />

Change [2016] 2 All ER 220. In the lower<br />

High Court earlier Coulson J had referred<br />

to a Government Consultation paper<br />

pointing out that some organisations had<br />

‘easy access to up-front, low-cost capital<br />

…’ This analysis prompted the proposed<br />

changes eventually resulting in the Breyer<br />

Group case. Various suppliers commenced<br />

litigation against the Department, and<br />

their claims were based on ‘A1P1 ECHR’.<br />

This is jargon for Article 1 of the First<br />

Protocol of the European Convention on<br />

Human Rights. It provides, ‘Every natural<br />

or legal person is entitled to the peaceful<br />

enjoyment of his possessions. No one<br />

shall be deprived of his possessions except<br />

in the public interest and subject to the<br />

conditions provided for by law and by the<br />

general principles of international law.’<br />

The State was given powers to interfere in<br />

limited circumstances. These provisions<br />

and the Convention generally have been<br />

incorporated into law in the UK by the<br />

Human Rights Act 1998.<br />

In the light of these provisions the<br />

claimants alleged that they had possession<br />

rights in an enforceable legitimate<br />

expectation concerning the timing of the<br />

rates payable, the marketable goodwill,<br />

the signed contracts agreeing the FIT<br />

payments and much more. The judges<br />

would consider whether the Department<br />

had unjustifiably interfered with these<br />

alleged A1P1 possessions, and if any<br />

damages would be awarded.<br />

Coulson J approved Levison J’s<br />

statement in Murungaru v Secretary of<br />

State for the Home Department (2008)<br />

EWCA Civ 1015 that a contractual right<br />

could be such a right in possession.<br />

That would include signed and perhaps<br />

part-performed contracts, but not to<br />

those which were unsigned. Loss of<br />

future income was similarly excluded,<br />

but goodwill could be a possession for<br />

the purposes of the Convention. The<br />

exceptions would eliminate many of the<br />

claims.<br />

As for the proposal itself the defendant<br />

had acted unlawfully. The consultation<br />

document and written ministerial<br />

statement was an unlawful act of<br />

interference. The possessions included<br />

those contracts concluded before 31<br />

October 2011, which could not, for<br />

example, proceed as planned.<br />

Advancing the credit profession / www.cicm.com / <strong>September</strong> <strong>2021</strong> / PAGE 34