Mexican Revolution Edition 2021 I Quién es Quién Sin Fronteras

Free digital magazine, Mexican Revolution Edition 2021 I Quién es Quién Sin Fronteras, which publishes articles about culture, tourism, economy, development and more

Free digital magazine, Mexican Revolution Edition 2021 I Quién es Quién Sin Fronteras, which publishes articles about culture, tourism, economy, development and more

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

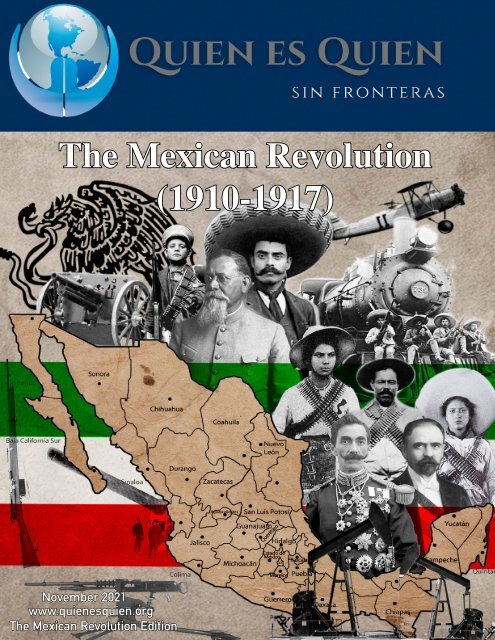

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

(1910-1917)<br />

November <strong>2021</strong><br />

www.quien<strong>es</strong>quien.org<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

(1910 - 1917 )<br />

accumulated wealth<br />

in the power of only a<br />

few, and the extreme<br />

poverty of the majority<br />

of the people.<br />

The subhuman conditions<br />

of the farmers,<br />

who, in addition to<br />

lacking land for cultivation,<br />

suffered the<br />

mistreatment of the<br />

foremen, prevailing<br />

at all tim<strong>es</strong> the conditions<br />

of servitude.<br />

Who´s Who<br />

General Director<br />

Carlos Castillo<br />

Director Administrativo<br />

Juan Coronel<br />

Editorial Director<br />

Alejandro Araujo<br />

Marketing Director<br />

Trinidad Ravelo<br />

Redaction<br />

M. Rodríguez<br />

Citlalli Puente<br />

“<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> <strong>Quién</strong><br />

<strong>Sin</strong> <strong>Fronteras</strong>”<br />

T<br />

he <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

was an<br />

armed movement<br />

initiated in 1910 to<br />

end the dictatorship of<br />

General Porfirio Diaz.<br />

It officially culminated<br />

with the promulgation<br />

of the new Political<br />

Constitution of the<br />

United <strong>Mexican</strong> Stat<strong>es</strong><br />

of 1917, the first in<br />

the world to recognize<br />

social guarante<strong>es</strong> and<br />

collective labor rights.<br />

At the beginning of<br />

Porfirio Diaz’s mandate,<br />

there were<br />

uprisings of people<br />

belonging to the old<br />

liberal regime. This,<br />

combined with a seri<strong>es</strong><br />

of political, economic,<br />

and social<br />

events, was the critical<br />

point for the emergence<br />

of the <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> movement.<br />

Its origin can be defined<br />

as the r<strong>es</strong>ult of<br />

the following caus<strong>es</strong>.<br />

Political Caus<strong>es</strong>:<br />

An aging regime in<br />

the absence of integration<br />

or formation<br />

of new leaders and<br />

the natural drive of<br />

the new generations.<br />

Social Caus<strong>es</strong>:<br />

The poor administration<br />

of justice, the<br />

Likewise, the working<br />

conditions of the<br />

factory workers, with<br />

long working hours<br />

ranging from 14 to<br />

16 hours a day in exchange<br />

for a miserable<br />

and unfair salary.<br />

The adoption of<br />

French culture over<br />

nationalist culture,<br />

but above all, the inability<br />

shown by General<br />

Porfirio Diaz to understand<br />

the needs of<br />

social justice and political<br />

participation.<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

<strong>Edition</strong> 1910-1917<br />

Pictur<strong>es</strong> and information<br />

from “Las Fuerzas Armadas<br />

en la Revolción <strong>Mexican</strong>a”<br />

e-mail<br />

info@quien<strong>es</strong>quien.org<br />

Web Page<br />

www.quien<strong>es</strong>quien.org<br />

Frontier Magazin<strong>es</strong><br />

Productions<br />

2000 Sur McColl<br />

Suite B-128<br />

McAllen, Tx.<br />

CP 78503<br />

tel. (956) 309 - 3846<br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras<br />

All Rights R<strong>es</strong>erved<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

CONTENTS<br />

Francisco Villa and<br />

the North Division......................................................................Page 5<br />

The North Division<br />

and the objectiv<strong>es</strong> of<br />

the <strong>Revolution</strong> ..............................................................Page 9<br />

The War Campaings:<br />

“Orozco, Huerta<br />

And Villa” ...........................................................Page 12<br />

Minors in the<br />

<strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>..........................................................Page 17<br />

The Women´s<br />

participations ..........................................................Page 23<br />

Tragic Decade ...................................................Page 26<br />

The US<br />

Intervention ..........................................................Page 27<br />

Consummation<br />

of the <strong>Revolution</strong> ..........................................................Page 29<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong>

Francisco Villa and<br />

the North Division<br />

F<br />

rancisco Villa, a character<br />

of great popularity in the<br />

history of Mexico. His real<br />

name was Doroteo Arango Arámbula,<br />

born in La Coyotada, near<br />

the Rio Grande ranch, Municipality<br />

of San Juan del Rio, State<br />

of Durango, on June 5, 1878. It<br />

is known that he did not attend<br />

school and was orphaned at an<br />

early age.<br />

In September 1894, according<br />

to his autobiography, he wounded<br />

Agustín López Negrete, a landowner<br />

who wanted to take advantage<br />

of his younger sister, so<br />

he had to flee from the hacienda<br />

and take refuge in the Silla and<br />

Gamón mountains.<br />

Having adopted the name of<br />

Francisco Villa, he dedicated to<br />

cattle rustling as his main activity,<br />

but he also worked as a miner,<br />

bricklayer, tanner, and butcher.<br />

Shortly after, he moved to the<br />

state of Chihuahua, where he met<br />

Abraham González, Pr<strong>es</strong>ident of<br />

the Anti-Reelectionist Club of the<br />

state, in 1909, who convinced him<br />

to join the armed movement and<br />

sent him to Sierra Azul, located<br />

south of the state, to organize an<br />

armed uprising against the government<br />

of General Porfirio Díaz.<br />

For a few weeks, he was in the<br />

Page 6<br />

rebel group of rebel Cástulo Herrera.<br />

Still, his personality and<br />

leadership qualiti<strong>es</strong> allowed him to<br />

be appointed leader of the region’s<br />

revolutionari<strong>es</strong>. He participated in<br />

the actions of Bajío del Tecolote,<br />

San Andrés, Camargo and Las Escobas,<br />

in which he was defeated.<br />

When he learned that Don Francisco<br />

I. Madero was in the state of<br />

Chihuahua, he immediately joined<br />

him in the town of Bustillos, in<br />

April 1911, where Madero granted<br />

him the rank of Colonel. From<br />

the first meeting, both characters<br />

formed a good friendship. Villa<br />

immediately subordinated himself<br />

to Madero, believing that Madero<br />

was fighting for the welfare of the<br />

people.<br />

On May 9, 1911, while the revolutionary<br />

troops were on the<br />

outskirts of Ciudad Juarez, Villa<br />

and Pascual Orozco noticed that<br />

keeping the plaza under siege was<br />

a waste of time, so they decided<br />

to take it, with blood and fire.<br />

Afterward, Villa and Orozco had<br />

disagreements with Madero because<br />

of General Juan S. Navarro,<br />

who defended said plaza. Villa and<br />

Orozco wanted to shoot him, but<br />

Madero set him free. So the leader<br />

from Durango left his troops and<br />

retired to civilian life after receiv-<br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Page 7<br />

ing compensation for the servic<strong>es</strong><br />

rendered to the revolution.<br />

The Northern Division<br />

In February 1912, when the rebellion<br />

led by Orozco took place,<br />

Villa left Chihuahua City, gathering<br />

approximately 500 men. He confronted<br />

the rebels in several actions<br />

and finally joined the Northern<br />

Division of the Federal Army,<br />

commanded by General Victoriano<br />

Huerta. A unit with which he actively<br />

participated in Tlahualilo,<br />

Conejos, Escalon, and Rellano, in<br />

which Pascual Orozco was defeated,<br />

for which the Secretary of War<br />

and Navy granted Villa the rank of<br />

Honorary Brigadier General.<br />

When taking a town, Villa first<br />

informed himself of the situation.<br />

Then he demanded food and money<br />

from the authoriti<strong>es</strong> and merchants<br />

to pay his troops, leaving<br />

them vouchers so that when the<br />

cause triumphed, they would be<br />

paid. Finally, he would order to<br />

open the merchant’s stor<strong>es</strong> so that<br />

the people could take what they<br />

needed. This is why they were<br />

seen as liberators and had followers<br />

loyal to the cause.<br />

On August 26, 1913, Francisco<br />

Villa, with a little more than 1,000<br />

men, took San Andr<strong>es</strong>, Chih., defended<br />

by the Orozquistas, commanded<br />

by Felix Terrazas; the<br />

Battle lasted several hours, and finally,<br />

the defenders had to vacate<br />

the square. The villistas seized<br />

seven trains, two cannons, 421 rifl<strong>es</strong>,<br />

and about 20,000 cartridg<strong>es</strong>.<br />

Against all expectations, Villa<br />

went to Camargo, Chihuahua,<br />

where he was joined by the revolutionari<strong>es</strong><br />

Maclovio Herrera with<br />

his Benito Juarez Brigade and Trinidad<br />

Rodriguez. They had accepted<br />

the “Centaur of the North” as<br />

Chief.<br />

Villa’s first action as Chief of the<br />

Northern Division was attacking<br />

Lerdo, Gómez Palacio, and Torreón,<br />

which were defended by<br />

about 5,000 men, commanded by<br />

General Eutiquio Munguía. Of the<br />

total federal troops, more than<br />

half were Orizquistas led by Benjamín<br />

Argumedo. Villa ordered<br />

the “Benito Juarez” and “Madero”<br />

brigad<strong>es</strong>, supported by a fraction<br />

of the “Juarez de Durango,”<br />

which had the “Volunteers of the<br />

Lagoon” as a r<strong>es</strong>erve, to advance<br />

along the north bank of the Nazas<br />

River.<br />

When Francisco Villa took command<br />

of the Northern Division,<br />

his main concern was to organize<br />

a great unit, the “undisciplined<br />

rabble,” into a well-organized<br />

body. Above all, he wanted to<br />

sow in his people that the cause<br />

for which they were fighting was<br />

the <strong>Revolution</strong>, that the fight was<br />

against all those who exploited<br />

the poor and humiliated, against<br />

those who persecuted and dishonored<br />

them. The objective of<br />

their struggle was to overthrow<br />

the dictatorship that was becoming<br />

unbearable due to the lack of<br />

justice and liberti<strong>es</strong>.<br />

The Northern Division was<br />

a great unit that came out of<br />

nowhere, that broke all the<br />

schem<strong>es</strong> of the armi<strong>es</strong> of the<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> since it was joined by<br />

all kinds of people from diverse<br />

origins. From bandits, peasants,<br />

ranchers, miners to members of<br />

the middle class and prof<strong>es</strong>sional<br />

military.<br />

A great number of the members<br />

of the Northern Division joined<br />

this unit because Villa was an authentic<br />

leader who was followed<br />

unconditionally by a significant<br />

number of regional chiefs who<br />

obeyed his orders almost blindly<br />

because of his fight against the<br />

rich and his generosity with the<br />

poor.<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

The Northern Division and<br />

the objectiv<strong>es</strong> of the revolution<br />

O<br />

n November 2, 1913, in<br />

Estación Consuelo, Chihuahua<br />

Villa asked General<br />

Mercado to surrender the<br />

plaza of Chihuahua or leave it<br />

to fight in the open field, which<br />

was rejected. The villistas took<br />

positions for the battle while the<br />

defenders prepared to defend<br />

themselv<strong>es</strong>, taking advantage of<br />

the terrain conditions.<br />

After the setback in Chihuahua,<br />

Villa decided to take Ciudad<br />

Juarez. For effect, the villistas<br />

captured a coal train and<br />

forced the telegraphists to send<br />

m<strong>es</strong>sag<strong>es</strong> to the station chief of<br />

Ciudad Juarez that they had returned<br />

to the border city.<br />

The next objective of the<br />

Northern Division was the Chihuahua<br />

Plaza, but they had to<br />

take it before reinforcements<br />

arrived from Torreon, while internal<br />

problems grew stronger.<br />

Knowing that the federal forc<strong>es</strong>,<br />

mainly orozquistas or colorados,<br />

were heading to Ciudad<br />

Juarez to confront the Northern<br />

Division, Villa decided to confront<br />

them in an open zone.<br />

The Tierra Blanca station, 31<br />

kilometers south of the old Paso<br />

del Norte. The Battle of Tierra<br />

Blanca began on November 24,<br />

obtaining a victory of great importance<br />

for the <strong>Revolution</strong>.<br />

Villa’s next objective was to<br />

take Ojinaga and wipe out the<br />

federal troops in the state of<br />

Chihuahua. Hundreds of soldiers<br />

crossed the Bravo River and<br />

took refuge in the United Stat<strong>es</strong>.<br />

Many others d<strong>es</strong>erted and<br />

joined Villa, who remained lost,<br />

without artillery, almost without<br />

a park, and were defeated before<br />

starting the battle, fighting<br />

only for pride.<br />

It is worth mentioning that<br />

while a part of the Northern Division<br />

made an effort to control<br />

the state of Chihuahua, another<br />

part stayed in Torreon and<br />

northern Durango, having several<br />

confrontations in Saltillo,<br />

General Cepeda, Parras and Vi<strong>es</strong>ca,<br />

Coah. In this situation, a<br />

new Brigade was integrated, the<br />

Carranza, with people from the<br />

Carranza Regiment of the First<br />

Brigade of Durango, which from<br />

its creation was considered part<br />

of the Northern Division.<br />

In March 1914, the Northern<br />

Division went to La Laguna<br />

to recover the towns of Torreón,<br />

Gómez Palacio, and Lerdo,<br />

which were defended by the<br />

Nazas Division of the Federal<br />

Army. After controlling the lagoon<br />

region, Villa had several<br />

Página Page 10<br />

problems with Venustiano Carranza.<br />

He tried to solve it in the<br />

b<strong>es</strong>t way and even marched to<br />

take the plaza of Saltillo, Coahuila,<br />

knowing that this was<br />

part of the territory that corr<strong>es</strong>ponded<br />

to the Northeastern<br />

Army Corps.<br />

Villa r<strong>es</strong>igned as commander<br />

of the Northern Division. Still,<br />

his brigade chiefs did not accept<br />

the r<strong>es</strong>ignation, and all of them<br />

unsubordinated against Carranza’s<br />

order saying that Villa was<br />

the only commander they recognized.<br />

Finally, “The Centaur of<br />

the North” continued to lead the<br />

Division and went to Zacatecas,<br />

not to support Nátera, but to<br />

take the town, to show Carranza<br />

the strength of his troops.<br />

The taking of Zacatecas was<br />

the bloodi<strong>es</strong>t of the battl<strong>es</strong> of<br />

the <strong>Revolution</strong> and the most<br />

significant and most brilliant<br />

action of the Northern Division,<br />

in which the artillery directed by<br />

General Felipe Ángel<strong>es</strong> stands<br />

out; this battle was planned<br />

with the basic principl<strong>es</strong> of military<br />

art.The city of Zacatecas<br />

had strategic importance for<br />

both the Constitutionalist Army<br />

and the Federal Army since it<br />

was a railroad crossing, which<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Page 11<br />

was the obligatory passage from<br />

the North of the country to Mexico<br />

City. This victory is considered<br />

a masterpiece of military<br />

science. The villistas captured<br />

6,000 prisoners, 12 cannons,<br />

300 machine guns, and 12 rifl<strong>es</strong>.<br />

With this victory, the Constitutionalists<br />

had a free road to<br />

Mexico City, and it was the decisive<br />

blow for the fall of General<br />

Victoriano Huerta’s government.<br />

However, in the Bajío, the<br />

r<strong>es</strong>ults in combat were not as<br />

expected, and the Northern Division<br />

ceased to exist in 1915;<br />

Villa, with a small group of his<br />

loyal troops, took refuge in the<br />

state of Chihuahua, returning to<br />

guerrilla life.<br />

One of the objectiv<strong>es</strong> of the<br />

thousands of men who made<br />

the <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> possible<br />

was to change society, to make<br />

it fairer so future generations<br />

would have a more dignified life<br />

than they or their anc<strong>es</strong>tors.<br />

Francisco Villa was one of those<br />

thousands of <strong>Mexican</strong>s who<br />

joined the revolutionary maelstrom<br />

and, with his contribution,<br />

influenced chang<strong>es</strong> in all areas<br />

of <strong>Mexican</strong> society.We can assure<br />

that since Villa joined the<br />

revolution in November 1910,<br />

until his entrance to Mexico City<br />

in December 1915, he did not<br />

issue any document in favor of<br />

the farmers or workers. However,<br />

after he joined the Zapatistas,<br />

he was influenced by the<br />

farmers of the south. In May<br />

1915, he issued the General<br />

Agrarian Law to fulfill the revolutionary<br />

promis<strong>es</strong> and as a basis<br />

for the country’s pacification.<br />

Although General Villa was<br />

defeated in the battl<strong>es</strong> of Celaya<br />

and La Trinidad in April-May<br />

1915, and his agricultural project<br />

could not be carried out, its<br />

foundations were embodied in<br />

the Constitution of 1917. D<strong>es</strong>pite<br />

the Magna Carta being<br />

drafted by the constitutionalists,<br />

the victors of the Northern<br />

Division fulfilled part of the objectiv<strong>es</strong><br />

sought by all <strong>Mexican</strong>s<br />

who decided to fight in the <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>.<br />

The Magna Carta of 1917 was<br />

the pinnacle in which the regenerative<br />

movement reflected its<br />

ideals of equality and social justice<br />

that still govern the liv<strong>es</strong> of<br />

all <strong>Mexican</strong>s. Foundations that<br />

since its promulgation has been<br />

a guide to issue the rul<strong>es</strong> that<br />

currently govern the <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

state to achieve the welfare of<br />

the <strong>Mexican</strong> people.<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

T<br />

The War Campaigns:<br />

Huerta, Orozco and Villa<br />

he History of the Northw<strong>es</strong>t<br />

Army Corps is part of the<br />

golden pag<strong>es</strong> of the History<br />

of the <strong>Mexican</strong> Army and the History<br />

of Mexico. Its actions were of<br />

utmost relevance in the <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> of 1910: The defeats of<br />

General Pascual Orozco and General<br />

Francisco Villa.<br />

The background of the Northw<strong>es</strong>t<br />

Army begins at the beginning<br />

of 1912 when some groups that<br />

at first had supported the Plan of<br />

San Luis, proclaimed by Francisco<br />

I. Madero pronounced themselv<strong>es</strong><br />

against it. Specifically, it has its<br />

origin with Orozco’s ignorance<br />

against Madero’s regime.<br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras<br />

The campaign against<br />

General Orozco<br />

Pascual Orozco was a native of<br />

Chihuahua, rancher, muleteer, and<br />

merchant. He was the first leader<br />

of the armed movement and is<br />

credited with the victory over the<br />

federal troops guarding the plaza<br />

of Ciudad Juarez, with which General<br />

Porfirio Diaz r<strong>es</strong>igned from<br />

the pr<strong>es</strong>idency.<br />

However, due to misunderstandings<br />

between General Orozco and<br />

Madero, mainly because the latter<br />

did not attend to the demands of<br />

social justice and left the structure<br />

of the federal army intact, Orozco<br />

disowned him as pr<strong>es</strong>ident on<br />

March 3, 1912.

Page 13<br />

The first confrontations between<br />

Orozco’s supporters and federal<br />

forc<strong>es</strong>, commanded by General<br />

José González Salas, took place in<br />

Chihuahua, on March 23, 1912, in<br />

Rellano. The former achieved victory<br />

and two days later expr<strong>es</strong>sed<br />

their demands in a manif<strong>es</strong>to<br />

known as the “Plan de la Empacadora.”<br />

At the end of May, a second confrontation<br />

took place in the Rellano<br />

square. This time the federal<br />

army, commanded by General Victoriano<br />

Huerta, managed to defeat<br />

the insurgents and little by little<br />

managed to decimate their forc<strong>es</strong><br />

until gaining control of Chihuahua<br />

and Ciudad Juarez on August 16<br />

of that year. After being wounded<br />

in a confrontation in the city of<br />

Ojinaga, Orozco took refuge in the<br />

neighboring country to the north,<br />

where he rethought his strategy.<br />

Upon his return in December1912,<br />

Orozco’s priority was<br />

to gain supporters. He began an<br />

arduous campaign to recruit rural<br />

workers, and former Maderista<br />

combatants discharged after the<br />

revolutionary triumph, members<br />

of the federal army, and anyone<br />

who decided to support him.<br />

On September 19, at Rancho de<br />

San Joaquín, the Maderista forc<strong>es</strong><br />

prevailed again against the<br />

Oozquistas d<strong>es</strong>pite their numerical<br />

inferiority. Obregón was promoted<br />

to the rank of colonel for demonstrating<br />

his skills in the science of<br />

war. The victori<strong>es</strong> of the Maderista<br />

groups helped immensely in the<br />

defeat of Pascual Orozco.<br />

The campaign against<br />

Victoriano Huerta<br />

In 1913, Venustiano Carranza<br />

had disowned the government of<br />

General Victoriano Huerta and had<br />

initiated the organization of the<br />

Constitutionalist Army, of which he<br />

was the First Chief and whose purpose<br />

was to defend the principl<strong>es</strong><br />

of the Magna Carta.<br />

A decree was issued in the city<br />

of Monclova, Coahuila, which stipulated<br />

the organization of the<br />

Constitutionalist Army in seven<br />

Army Corps: corr<strong>es</strong>ponding to<br />

the Northw<strong>es</strong>t, Northeast, East,<br />

W<strong>es</strong>t, Center, South, and Southeast.<br />

However, only three fractions<br />

of this army went into effect, the<br />

Army Corps of the Northw<strong>es</strong>t and<br />

Northeast and the Northern Division,<br />

under the command of Francisco<br />

Villa.<br />

Throughout 1914, the Northw<strong>es</strong>t<br />

Army fought three <strong>es</strong>sential<br />

battl<strong>es</strong> in its march towards the<br />

south. Of which, the following<br />

stand out; the capture of Tepic,<br />

Nayarit, the Battle of La Venta-Orendain,<br />

and the capture of<br />

Colima.<br />

With th<strong>es</strong>e victori<strong>es</strong>, the revolutionary<br />

army managed to control<br />

the northw<strong>es</strong>t and w<strong>es</strong>t of the<br />

country. This let General Obregón<br />

advance towards Mexico City, and<br />

thanks to the victory of the Northern<br />

Division in Zacatecas, the passage<br />

was unstoppable.<br />

Thus, on July 15, 1914, Victoriano<br />

Huerta left the country’s pr<strong>es</strong>idency<br />

in the hands of Carvajal<br />

to hand it over to the triumphant<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>, with the signing of the<br />

Treati<strong>es</strong> of Teoloyucan, on August<br />

13, 1914.<br />

Alvaro Obregón’s troops entered<br />

the country’s capital on August<br />

15 and, on the 20th of the same<br />

month, Venustiano Carranza entered<br />

Mexico City, thus becoming<br />

Provisional Pr<strong>es</strong>ident of Mexico.<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Page 15<br />

Page 16<br />

The campaign against<br />

General Francisco Villa<br />

After disarming the Constitutionalist<br />

troops, Carranza appointed<br />

his cabinet. However, a<br />

long-standing rivalry, added to recent<br />

events, provoked the rupture<br />

between the First Chief and the<br />

General in Chief of the Northern<br />

Division, Francisco Villa, who until<br />

then had fought on the Constitutionalist<br />

side.<br />

Because of the disagreements<br />

between the Carrancistas and Villistas<br />

and the still revolted Zapatistas,<br />

a Convention was called to<br />

meet first in Mexico City, on October<br />

1st, and later in Aguascalient<strong>es</strong>,<br />

to r<strong>es</strong>olve the situation.<br />

Due to the irreconcilable positions<br />

of both Carranza and General<br />

Villa, the Aguascalient<strong>es</strong> Convention<br />

agreed to remove both from<br />

their posts and appoint General<br />

Eulalio Gutiérrez as Provisional<br />

Pr<strong>es</strong>ident who in turn was forced<br />

to appoint General Villa as Chief of<br />

the Conventionist Army.<br />

Faced with this ruse, Carranza<br />

refused to accept the decision<br />

of the Convention, giving rise to<br />

what some authors call the third<br />

stage of the <strong>Revolution</strong> or the<br />

“Factional Struggle” between Carranza<br />

and Villa, joined by the Liberation<br />

Army of the South, led by<br />

Emiliano Zapata.<br />

On December 3, 1914, General<br />

Villa entered Mexico City at the<br />

head of the conventionist troops.<br />

Evidently, Carranza did not accept<br />

this imposition, and the country<br />

was trapped in the middle of two<br />

governments and again plunged<br />

into war. On the 14th, both sid<strong>es</strong><br />

fought fiercely. However, Villa’s<br />

troops began to retreat, and his<br />

strategy was maintained with few<br />

variations. On the 15th, given the<br />

succ<strong>es</strong>sful advance, the Army of<br />

Operations changed from a defensive<br />

tactic to an offensive one, and<br />

it was a double cavalry envelopment<br />

that consummated the victory.<br />

Due to the decimation of his<br />

troops, General Francisco Villa understood<br />

that he could not continue<br />

fighting as a formal army and<br />

decided to disintegrate the Northern<br />

Division and keep on fighting<br />

with a guerrilla-type strategy.<br />

In this way, in a short time, the<br />

Army of Operations managed to<br />

pacify the north of the country<br />

and continued with the task of dismembering<br />

the r<strong>es</strong>istance that still<br />

supported General Villa.<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Page 17<br />

Minors: Social Actors in<br />

the <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

T<br />

he <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> was<br />

the first significant social<br />

movement of the 20th century.<br />

It meant a violent change<br />

in the country’s political, economic,<br />

and social institutions, in<br />

which men, women, and minors<br />

(boys and girls) took part.<br />

To create and organize an<br />

army that would re<strong>es</strong>tablish the<br />

constitutional order in the national<br />

territory, the most important<br />

thing required, “the soldier.”<br />

It was recruited from the civilian<br />

population affected, both by<br />

the revolutionary side and the<br />

federal government, since both<br />

contenders extracted the farmers<br />

from the villag<strong>es</strong> and turned<br />

them into soldiers.<br />

Sometim<strong>es</strong> th<strong>es</strong>e were followed<br />

by their wiv<strong>es</strong> and children.<br />

This common practice is<br />

how minors were involved in<br />

war activiti<strong>es</strong>, and many others<br />

were born in a camp or a<br />

military barracks. During the<br />

development of the <strong>Revolution</strong>,<br />

they reached the age or<br />

size that would allow them to<br />

wield a weapon and fight in the<br />

same unit where their father<br />

was (who saw for the safety of<br />

his offspring), thus entering the<br />

revolutionary or federal ranks.<br />

Page 18<br />

In contrast with this, many<br />

other minors chose to join the<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>ary movement in<br />

search of adventure voluntarily.<br />

therefore, whatever their way<br />

of entering the <strong>Revolution</strong>, they<br />

had a daily attitude towards the<br />

belligerent activiti<strong>es</strong> in common,<br />

since th<strong>es</strong>e also corr<strong>es</strong>ponded<br />

to the social reality faced in the<br />

country.<br />

Being a minor in Mexico at the<br />

beginning of the 20th century<br />

did not mean being alienated<br />

from the r<strong>es</strong>ponsibiliti<strong>es</strong> of the<br />

daily life of adults, so biological<br />

age was not taken into account<br />

in the face of nec<strong>es</strong>sity and customs.<br />

For example, a 12-year-old<br />

boy was seen with the capacity<br />

to take r<strong>es</strong>ponsibiliti<strong>es</strong> and participate<br />

in his society, the same<br />

as a girl of the same age, who<br />

could get married, assuming the<br />

implications of the social role of<br />

a wife.<br />

Based on the laws in force at<br />

the time, the beliefs and customs<br />

of the people of Mexico,<br />

minors were subject to the reality<br />

facing the country in the revolutionary<br />

era.<br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Page 20<br />

in Guadalajara, state of Jalisco.<br />

She joined the revolutionary<br />

movement on February 11,<br />

1916, as a nurse at 16.<br />

She fought under the orders of<br />

the Zapatista General Martiniano<br />

Oznaya, who fought against the<br />

Huertista forc<strong>es</strong>. Her servic<strong>es</strong><br />

consisted of caring for the sick<br />

and wounded and carrying out<br />

commissions to acquire medicin<strong>es</strong><br />

and suppli<strong>es</strong> nec<strong>es</strong>sary for<br />

the service of the Zapatista forc<strong>es</strong>.<br />

On October 22, 1919, she<br />

separated from the army after<br />

being granted an absolute leave<br />

of absence.<br />

Cas<strong>es</strong> of<br />

female minors<br />

The primary role of female minors<br />

was to assist in the tasks<br />

of daily life, except for those<br />

who excelled as nurs<strong>es</strong>, propagandists,<br />

and m<strong>es</strong>sengers, exampl<strong>es</strong><br />

of th<strong>es</strong>e cas<strong>es</strong> are the<br />

following:<br />

Magdalena Cueva y Cueva,<br />

originally from Santa Marta, Jal.<br />

born May 25, 1896, entered the<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> in March 1913, at<br />

the age of 17, as a propagandist<br />

for the <strong>Revolution</strong>ary Junta.<br />

His last commission was to<br />

take some official letters from<br />

the Junta to General Manuel M.<br />

Diéguez, urging him to advance<br />

to the Plaza de Guadalajara. On<br />

June 19, 1914, he finished his<br />

accredited participation with the<br />

satisfactory fulfillment of the<br />

commission mentioned above.<br />

María J<strong>es</strong>ús Castro Patrón,<br />

was born on January 18, 1900,<br />

Esther Calvo de Campos, born<br />

November 2, 1900, in Torreón,<br />

Coahuila, joined the <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

in March 1914 at the age of 14<br />

in the General Headquarters of<br />

the Lucio Blanco column, serving<br />

as an auxiliary nurse. She<br />

separated from the army on August<br />

25, 1914, to continue her<br />

studi<strong>es</strong> as a stenographer.<br />

Cas<strong>es</strong> of<br />

male minors<br />

Juan Delgado Herrera, born<br />

July 2, 1899, in Ixcateopan,<br />

state of Guerrero, entered the<br />

revolutionary movement on<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Page 21<br />

February 16, 1911, as a private<br />

soldier, in the revolutionary forc<strong>es</strong><br />

of the Liberating Army of the<br />

South commanded by Emiliano<br />

Zapata participating in 12 battl<strong>es</strong>.<br />

Ambrosio Castro Cerda, born<br />

December 8, 1899, in Rancho<br />

de San Bernardo, Guanajuato<br />

State, joined the revolutionary<br />

movement on January 5, 1914.<br />

At the age of 15, he entered as<br />

a Cavalry Lieutenant in the revolutionary<br />

forc<strong>es</strong> of the Division<br />

commanded by General J<strong>es</strong>us<br />

Carranza.<br />

to affect national security and<br />

maintain territorial control.<br />

One of the measur<strong>es</strong> applied<br />

by Carranza was the suppr<strong>es</strong>sion<br />

of the Army Corps. For this<br />

purpose, he relied on Article 129<br />

of the Political Constitution of<br />

1917.<br />

This reorganization caused a<br />

significant number of chiefs and<br />

officers to be surplus; another<br />

decision to solve the surplus<br />

was to decree the discharge of<br />

minors, which reached very high<br />

numbers.<br />

Felipe Beltrán Cruz, a native<br />

of Tehuacán, Pue. was born on<br />

April 23, 1898, joined the <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

on July 3, 1916, at the<br />

age of 18 in the Constitutionalist<br />

forc<strong>es</strong> in the Zaragoza Regiment<br />

of General Ern<strong>es</strong>to Santos Coy,<br />

with the rank of Cavalry Soldier<br />

and was promoted by merit<br />

in the campaign to 1st Cavalry<br />

Sergeant.<br />

Minors after the<br />

constitutionalist triumph<br />

With the consolidation of the<br />

Constitutionalist triumph, Venustiano<br />

Carranza carried out<br />

actions to reduce the army not<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> State tried to mitigate<br />

some of the most painful<br />

effects of the <strong>Revolution</strong> on children:<br />

parental abandonment or<br />

death. Laws were <strong>es</strong>tablished to<br />

improve minors’ situation and<br />

r<strong>es</strong>tore the social and family<br />

welfare of the population. If education<br />

and child care had been<br />

secondary during the war, th<strong>es</strong>e<br />

aspects became the prioriti<strong>es</strong> of<br />

the new State once it was over.<br />

One of the immediate consequenc<strong>es</strong><br />

of the <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

was the promulgation of the<br />

Political Constitution of 1917.<br />

Among its fundamental articl<strong>es</strong>,<br />

123 stood out because one of<br />

its claus<strong>es</strong> <strong>es</strong>tablished that the<br />

minimum age for admission to<br />

work was 12 years of age. It<br />

also <strong>es</strong>tablished that children<br />

under 16 could not work more<br />

than six hours in unhealthy<br />

or dangerous conditions or at<br />

night.<br />

Social elements such as compulsory<br />

schooling and a new<br />

mentality regarding the child’s<br />

place in society contributed to<br />

the gradual negative social connotation<br />

of child labor, which led<br />

to a decrease in the work of minors.<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Women’s participation...<br />

T<br />

o better understand the<br />

pr<strong>es</strong>ence of women in the<br />

revolutionary proc<strong>es</strong>s, it is<br />

nec<strong>es</strong>sary to start from the fact<br />

that it was not a fortuitous event.<br />

The history of women in Mexico<br />

has countl<strong>es</strong>s exampl<strong>es</strong> of those<br />

who supported various social and<br />

armed movements out of nec<strong>es</strong>sity<br />

or conviction. During the <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>, the peculiarity<br />

of <strong>Mexican</strong> women, regardl<strong>es</strong>s of<br />

their origin, led thousands of them<br />

to join this struggle from different<br />

fronts.<br />

Page 24<br />

fought for rights and opportuniti<strong>es</strong><br />

that many men still could not<br />

conceive. There were two typ<strong>es</strong> of<br />

incorporation to the revolutionary<br />

movement. One of them was support<br />

from outside the ranks, from<br />

women who distributed propaganda,<br />

distributed information and<br />

obtained suppli<strong>es</strong> for the cause.<br />

The other was by taking up arms<br />

together with the men; among the<br />

women, we can highlight are Ramona<br />

R. Flor<strong>es</strong> “La Tigr<strong>es</strong>a,” Clara<br />

de la Rocha11 and Carmen Vélez<br />

“La Generala.”<br />

Adela Velarde Pérez joined the revolution in “la División del<br />

Norte del Ejército Constitucionalista”, then joined “el Cuerpo del<br />

Ejército del Nor<strong>es</strong>te”<br />

Women who had supported anti-reelection<br />

and others who had<br />

not yet been politically active condemned<br />

the actions of Pr<strong>es</strong>ident<br />

Diaz and showed their support for<br />

Madero. Among th<strong>es</strong>e women was<br />

Isabel Vargas Urquidi, who sheltered<br />

the persecuted Maderistas<br />

in her house. As well as Dolor<strong>es</strong><br />

Romero de Revilla, who had begun<br />

her political activity in 1909 and<br />

after the outbreak of the revolution,<br />

participated in various battl<strong>es</strong>.<br />

Many of the anti-reelection and<br />

maderista women were middle<br />

class, high, and usually educated.<br />

Hence, they began to conform<br />

to a feminist ideology that bothered<br />

some of Madero’s sympathizers<br />

since th<strong>es</strong>e educated women<br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras<br />

Another form of action was to<br />

provide information, an extremely<br />

risky task that required women<br />

versed in the subject, as they<br />

had to disguise themselv<strong>es</strong> as<br />

merchants and enter towns in enemy<br />

hands. For this reason, this<br />

was not constant practice, and it<br />

occurred particularly within the<br />

Zapatista army.<br />

In addition to taking up arms,<br />

women acted in a manner equivalent<br />

to the health service, helping<br />

the wounded in periods of confrontation.<br />

It is nec<strong>es</strong>sary to emphasize<br />

that all th<strong>es</strong>e activiti<strong>es</strong> in<br />

which women participated were<br />

not a single task since most of the<br />

women revolutionari<strong>es</strong> simultaneously<br />

performed the servic<strong>es</strong> of<br />

feeding, nursing, surveillance, etc.

Page 25 Page 26<br />

The Tragic Decade<br />

The Adelitas<br />

The popular inventiven<strong>es</strong>s inside<br />

and outside the troops led<br />

to different nicknam<strong>es</strong> and labels<br />

for the women who accompanied<br />

the armi<strong>es</strong>. This was<br />

done according to their situation<br />

within the ranks.<br />

There was also the “galletas,”<br />

who had been widowed several<br />

tim<strong>es</strong> due to war conditions and<br />

had more than one or two partners.<br />

Other nicknam<strong>es</strong> for female<br />

revolutionari<strong>es</strong> were “chimiscoleras”,<br />

“soldadas”, “juanas”,<br />

“cucarachas”, “argüenderas”,<br />

“mitoteras”, “busconas” and<br />

“hurgamanderas”.<br />

There was the so-called “jefas,”<br />

“vivanderas,” or “comideras.”<br />

Th<strong>es</strong>e were a group of older<br />

women who had already passed<br />

their concubine stage and were They are equally labeled, without<br />

dedicated to caring for soldiers<br />

distinction of sid<strong>es</strong>, as “adel-<br />

who did not have a partner, itas.” This denomination became<br />

among whom would usually be famous thanks to the song of<br />

their children who already belonged<br />

the same name that the División<br />

to an army due to their del Norte spread between 1914<br />

age.<br />

Mictlantecuhtli, and 1915. Dios Mexica de la Muerte<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

K<br />

nown as the Tragic Decade,<br />

a military coup against Francisco<br />

I. Madero began on<br />

February 9, 1913, in Mexico City<br />

when he was pr<strong>es</strong>ident. It lasted<br />

ten days and managed to overthrow<br />

and assassinate Madero and<br />

freed the dissident generals, Bernardo<br />

Rey<strong>es</strong> and Félix Díaz, who<br />

were imprisoned.<br />

The leaders of the Decena Trágica<br />

were Manuel Mondragón and<br />

Victoriano Huerta, who betrayed<br />

Madero by signing the embassy<br />

pact with the opponents. Among<br />

the caus<strong>es</strong> that gave rise to this<br />

movement were: Madero’s failure<br />

after trying to execute the governmental<br />

reforms d<strong>es</strong>ired by the<br />

revolutionary groups, his relations<br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras<br />

with political entiti<strong>es</strong> that supported<br />

former Pr<strong>es</strong>ident Diaz to<br />

r<strong>es</strong>tore and improve the economy<br />

and inv<strong>es</strong>tments abroad.<br />

The non-conformity and injustic<strong>es</strong><br />

towards the <strong>Mexican</strong> working<br />

class, the revolutionary ideas of<br />

the society of that time, where the<br />

repeated strik<strong>es</strong> sowed a feeling of<br />

change, and the trade polici<strong>es</strong> that<br />

prevented the entrance of foreign<br />

capital and led many compani<strong>es</strong> to<br />

close their doors, were influential.<br />

Consequently, Victoriano Huerta<br />

took over as Pr<strong>es</strong>ident of Mexico,<br />

leading to the failure to apply<br />

democratic polici<strong>es</strong> to the Republic,<br />

not to mention the assassination<br />

of Madero and Pino Suarez.

The northamerican intervention:<br />

the fear and the need to impose<br />

T<br />

he <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> threatened<br />

to spread to North<br />

American areas where Aztec<br />

people lived. On April 21, 1914,<br />

the U.S. Navy occupied Veracruz,<br />

killing 126 <strong>Mexican</strong>s in the proc<strong>es</strong>s.<br />

The next day, April 22, private<br />

guards of mining compani<strong>es</strong><br />

massacred strikers in Ludlow, Colorado.<br />

The U.S. intervention in the <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> was due to several<br />

factors. For the Americans,<br />

the United Stat<strong>es</strong> was r<strong>es</strong>ponsible<br />

for extending its authority over<br />

“semi-barbaric peopl<strong>es</strong>” such as<br />

the <strong>Mexican</strong>s.<br />

It was a matter of safeguarding<br />

U.S. inv<strong>es</strong>tments in Mexico and<br />

at the same time extending and<br />

deepening its influence and domination<br />

over that country.<br />

But at the same time, there was<br />

an underlying perception that the<br />

<strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> implied a profound<br />

potential danger to the United<br />

Stat<strong>es</strong>.<br />

Villa’s Invasion of<br />

the United Stat<strong>es</strong><br />

On the one hand, there were<br />

obvious aspects. Pancho Villa<br />

attacked the border town of Columbus<br />

in March 1916. D<strong>es</strong>pite<br />

the punitive expedition and the<br />

increase of troops on the border,<br />

Villa later repeated his penetration<br />

into U.S. territory to the<br />

point of going nearly 500 kilometers<br />

into the United Stat<strong>es</strong>.<br />

But even more important<br />

were the <strong>Mexican</strong> immigrants<br />

in Texas, since between 1910<br />

and 1912, between sixty and<br />

one hundred thousand <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

workers crossed the border annually<br />

to work. Th<strong>es</strong>e workers,<br />

coming from the areas affected<br />

by the revolutionary movement,<br />

brought their experience and<br />

demands.<br />

In the United Stat<strong>es</strong>, there was<br />

a prominent <strong>Mexican</strong> community<br />

whose actions could have<br />

profound effects under the influence<br />

of the revolutionary movement.<br />

Page 28<br />

From the point of view of<br />

American employers, the <strong>Mexican</strong><br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> was no longer an<br />

event in a neighboring country<br />

but a potential source of sedition<br />

that could affect their inter<strong>es</strong>ts<br />

and the system’s stability.<br />

<strong>Mexican</strong> workers in the United<br />

Stat<strong>es</strong> at the time were a militant<br />

and radicalized community<br />

with an admirable tradition of<br />

militant activity with strong ti<strong>es</strong><br />

to the <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>. In<br />

Texas, <strong>Mexican</strong> socialists organized<br />

their own people.<br />

<strong>Mexican</strong> farmers and laborers<br />

organized in the Tenant Farmers<br />

Union of America and the Land<br />

League of America throughout<br />

the Southw<strong>es</strong>t and attempted<br />

to organize a general strike. In<br />

1915, the <strong>Mexican</strong> community<br />

in South Texas began an armed<br />

separatist insurrection, which<br />

proposed the reunification of the<br />

Southw<strong>es</strong>t with Mexico or the<br />

<strong>es</strong>tablishment of a sovereign<br />

<strong>Mexican</strong> state.<br />

U.S. involvement was varied<br />

and seemingly contradictory,<br />

first supportive and then repudiating<br />

the <strong>Mexican</strong> regim<strong>es</strong>.<br />

For both economic and political<br />

reasons, the U.S. government<br />

generally supported those who<br />

occupied the seats of power,<br />

whether they legitimately held<br />

that power or not.<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras

Consummation<br />

of the <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

B<br />

y the end of 1916, Carranza’s<br />

position had been consolidated<br />

in almost all the<br />

stat<strong>es</strong> of Mexico, except for Chihuahua<br />

and Morelos.<br />

The time had come to legitimize<br />

the <strong>Revolution</strong>, approve<br />

a new Constitution, and be<br />

elected pr<strong>es</strong>ident. Therefore,<br />

in November 1916, he invited<br />

the new <strong>Mexican</strong> political<br />

class, mostly reformers from<br />

the middle class, to a constitutional<br />

convention in Santiago de<br />

Querétaro, Mexico.<br />

Thus, the promulgation of the<br />

1917 Constitution was confirmed,<br />

which included articl<strong>es</strong><br />

on church-state separation,<br />

national sovereignty over the<br />

subsoil, property rights of community<br />

groups over the lands of<br />

The <strong>Mexican</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Edition</strong>, November <strong>2021</strong><br />

their communiti<strong>es</strong>, the right of<br />

workers to organize, and go on<br />

strike, and many other aspirations.<br />

<strong>Quién</strong> <strong>es</strong> quién sin fronteras<br />

Like most constitutions, it was<br />

a statement of what the delegat<strong>es</strong><br />

wanted for <strong>Mexican</strong>s,<br />

not what could be carried out<br />

immediately. For Obregón, the<br />

reforms were going too slowly<br />

under Carranza; he rose in rebellion,<br />

and shortly after that,<br />

the pr<strong>es</strong>ident was assassinated.<br />

Obregón himself was elected<br />

pr<strong>es</strong>ident in 1920, carried out<br />

an agrarian reform in Morelos<br />

and Yucatán, and worked to improve<br />

Mexico’s financial situation.<br />

He was re-elected in 1928,<br />

only to be assassinated by a<br />

supporter of the pro-Catholic<br />

opposition shortly before retaking<br />

office.

Francisco I. Madero