Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

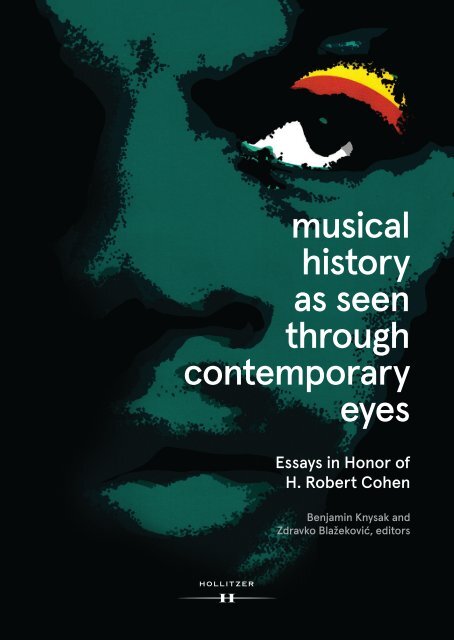

musical<br />

history<br />

as seen<br />

through<br />

contemporary<br />

eyes<br />

Essays in Honor of<br />

H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong><br />

Benjamin Knysak and<br />

Zdravko Blažeković, editors

Musical History<br />

As Seen Through<br />

Contemporary Eyes

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

MUSICAL HISTORY<br />

AS SEEN THROUGH<br />

CONTEMPORARY EYES<br />

Essays in Honor of<br />

H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong><br />

edited by<br />

Benjamin Knysak and Zdravko Blažeković<br />

3

4<br />

Introduction

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> at the International Musicological Society congress in Rome, 2012.<br />

5

Introduction<br />

Support for this volume was provided by the Barry S. Brook Center for Music Research and<br />

Documentation of the Graduate Center, City University of New York<br />

Benjamin Knysak and Zdravko Blažeković (eds.)<br />

Musical History as Seen through Contemporary Eyes. Essays in Honor of H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong><br />

Hollitzer Verlag, Vienna 2021<br />

Cover design: Fred Gates Design, New York.<br />

Image of Ornette Coleman interpreted from Jazz Magazine 1, no. 3 (Spring 1977). Used with permission.<br />

© Hollitzer Verlag, Vienna 2021<br />

www.hollitzer.at<br />

Layout: Nikola Stevanović<br />

Printed and bound in the EU<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this<br />

publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means,<br />

digital, electronic or mechanical, or by photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the<br />

Internet or a Web site without prior written permission of the publisher.<br />

Responsibility for the content and for questions of copyright lies with the author.<br />

ISBN 978-3-99012-973-9 (hbk)<br />

ISBN 978-3-99012-974-6 (pdf)<br />

6

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

CONTENTS<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond 13<br />

THE MUSICAL PRESS<br />

Malena Kuss<br />

A Ditty for a Friend: Honoring H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> through the Work of<br />

Zoila Lapique Becali (b. 1930), Doyenne of Cuba’s Musical Press 25<br />

Zoila Lapique Becali<br />

Nineteenth-Century Music in Cuban Periodicals (1822–1868) 29<br />

Marten Noorduin<br />

The International Tours of Charles Hallé<br />

as Viewed in the Contemporary Press 45<br />

Elvidio Surian<br />

Appunti sulla musica sacra in Italia nel Novecento 57<br />

Benjamin Knysak<br />

“That Derty Review”: John C. Freund from Oxford to New York 61<br />

Ruth Henderson<br />

Max Strakosch’s Rediscovered Memoir 83<br />

Max Strakosch<br />

Notes of Max Strakosch 85<br />

Richard Kitson<br />

Ursula Greville, Philip Heseltine and The Sackbut (London, 1920–1934) 109<br />

Antonio Baldassarre<br />

Serving “German music” and “the Great Empire of the Germans”:<br />

The German Periodical Musik im Kriege 125<br />

7

Introduction<br />

BERLIOZ, FRANCE AND VERDI<br />

Peter Bloom<br />

Berlioz and the Panthéon—Then and Now 183<br />

Catherine Massip<br />

Hector Berlioz (… et les autres) dans<br />

l’Illustration de Bade et d’Alsace (1858–1867) 201<br />

Joost van Gemert<br />

A Multifaceted Debate: French, German and Dutch Views<br />

on Gregorian Chant in Nineteenth-Century Periodicals 217<br />

Allan W. Atlas<br />

The Binfields and the Dulckens:<br />

The English Concertina in mid-Nineteenth-Century Paris (and Brussels) 237<br />

Ralph P. Locke<br />

André Messager’s Les p’tites Michu and the Marvels of French Light Opera:<br />

A Review and Appreciation 259<br />

John H. Roberts<br />

Recalled to Life: The Grands Opėras of Charles Gounod 281<br />

Jennifer A. Ward<br />

“Oui, j’existe”: Marie Bobillier and the French<br />

Musical Sources in Robert Eitner’s Quellen-Lexikon 301<br />

Peter Sühring<br />

Der Scherz des Falstaff war nicht sein letztes Wort. Verdis Sakralmusik 321<br />

MUSIC ICONOGRAPHY<br />

Zdravko Blažeković<br />

The Early Years of the Répertoire International d’Iconographie Musicale 345<br />

Florence Gétreau<br />

Three Founders of Music Iconography in France:<br />

Geneviève Thibault de Chambure, Albert Pomme de Mirimonde,<br />

and François Lesure 381<br />

8

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

Luísa Cymbron<br />

Bringing the S. Carlos Theater into the Home: Opera, Illustrated Journalism<br />

and Sound Transmission Technologies in Late Nineteenth-Century Lisbon 413<br />

Frits Zwart<br />

To the Cinema with Willem Mengelberg:<br />

A Meeting with Stokowski and Tchaikovsky 433<br />

Tatjana Marković<br />

“Oriental” memories: Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac’s ballad Lem Edim 445<br />

POPULAR MUSICS AND R-PROJECTS<br />

John M. Ehrenburg<br />

If You Want to Learn to Play Jazz, Pick Up That Magazine<br />

or<br />

A Critical (Re)Introduction to Pedagogical Content Published<br />

in the Jazz Press, 1914–1947 469<br />

Emile Wennekes<br />

Bob, Boris, and Boudewijn: H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong>’s international<br />

footsteps elucidated through three singer-songwriters 487<br />

Barbara Dobbs Mackenzie<br />

A Tale of Two R-Project Directors 501<br />

Jean-Michel Nectoux, Don Roberts<br />

Words of Thanks 513<br />

TABULA GRATULATORIA 517<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF H. ROBERT COHEN 521<br />

9

10<br />

Introduction

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

11

12<br />

Introduction

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

MUSICAL DOCUMENTATION OF A<br />

“FORGOTTEN CENTURY” AND BEYOND<br />

In 1968, to inaugurate the establishment of a new Ph.D. program at the City<br />

University of New York (CUNY), the chair of this foundling department,<br />

Barry S. Brook (1918–1997), invited fifteen distinguished scholars to give lectures<br />

on different aspects of the growing discipline of musicology. 1 Providing<br />

the first lecture in this series was none other than Gustave Reese (1899–1977),<br />

Professor of Music at nearby New York University, founding member of the<br />

American Musicological Society, and a distinguished figure in the field. In<br />

the course of his lecture, Reese provides an overview of musicology in the<br />

late 1960s: its foundations, status and growth in American academia; divisions<br />

of the discipline; prominent specializations; and lacunae. 2 Reflecting<br />

the postwar musicological focus on music of earlier eras, Reese describes the<br />

nineteenth century as a period requiring “an immense amount of work,” summarizing<br />

it as a musicologically–“forgotten century.” 3<br />

One of Reese’s students, H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong>, took up this charge over the<br />

following five decades. <strong>Cohen</strong>’s efforts brought to scholarly attention a trove<br />

of nineteenth-century musical iconography, staging manuals, Italian figurini,<br />

and above all, the vast musical press from the eighteenth through the twentieth<br />

centuries. In total, his contributions to the discipline as author, editor, and<br />

director comprises some 327 printed volumes, one journal, numerous articles,<br />

and four databases which contain nearly two million full text pages, more<br />

than a million annotated citations, and treat some six hundred music journals.<br />

Howard Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> was born in Baltimore, Maryland, and studied music<br />

in his youth, performing on clarinet and saxophone, absorbing music ranging<br />

from orchestral works to performances at local jazz clubs. <strong>Cohen</strong> attended New<br />

York University, obtaining a Bachelor of Arts (1963), Master of Arts (1967),<br />

and Ph.D. (1973). Interested in music in nineteenth-century France, specifically<br />

the writings and criticism of Hector Berlioz, he traveled to Paris on a Fulbright<br />

grant where he pursued much of the research for his Ph.D. dissertation,<br />

1 These essays were collected and published in 1972 by W.W. Norton and republished in 1975<br />

in a paperback edition. Perspectives in Musicology, ed. Barry S. Brook, Edward O.D. Downes,<br />

and Sherman Van Solkema (New York: W.W. Norton, 1972).<br />

2 Gustave Reese, “Perspectives and Lacunae in Musicological Research. Inaugural Lecture.”<br />

Ibid, 1–14.<br />

3 Ibid., 10.<br />

13

Introduction<br />

“Berlioz at the Opéra (1829–1849): A Study in Music Criticism.” 4 Concurrently,<br />

he served as a Maître-Assistant professor at the Université de Paris VIII from<br />

1968 to 1972. Owing to the French difficulty in pronouncing Howard (phonetically<br />

in French, awaʁ) he began using H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> professionally, to<br />

which we now know him.<br />

During this period in Paris, <strong>Cohen</strong> observed les évènements de 1968 firsthand,<br />

from both the street level and in the university, where he became perhaps<br />

the first person to teach the history of jazz at the Université de Paris and<br />

published his first article, on the music of Bob Dylan, who <strong>Cohen</strong> heard in<br />

New York’s Greenwich Village while he was a student. 5 In 1972, <strong>Cohen</strong> returned<br />

to North America when he was appointed to the faculty of Université<br />

Laval in Québec where he directed graduate studies and served as Director of<br />

the European Studies Program. It is from here that his next foray into archival<br />

sources occurred when he happened upon the music iconography published<br />

in the French journal L’Illustration. A weekly beginning in 1843, the journal<br />

lavishly depicted musical life in Paris and published more than three thousand<br />

images depicting musical life in the nineteenth century alone. <strong>Cohen</strong>’s resulting<br />

three-volume catalog and study of the musical iconography in L’Illustration<br />

was published under the auspices of the recently-established Répertoire International<br />

d’Iconographie Musicale (RIdIM) in 1982 and 1983, a project which<br />

received significant critical praise. 6<br />

In subsequent years, <strong>Cohen</strong> continued to uncover and compile documentary<br />

resources. Growing from his Berlioz research, he was instrumental in the<br />

foundation and initial publication of the complete musical criticism of Berlioz,<br />

published as La critique musicale in ten volumes between 1996 and 2020<br />

(Paris: Buchet-Chastel). <strong>Cohen</strong> served as co-editor of the first volume and<br />

directed the assembly of Berlioz’s original texts. He published volumes studying<br />

and cataloging mise-en-scène in France in the 1980s and the 1990s. 7 At the<br />

4 Howard Robert <strong>Cohen</strong>, “Berlioz at the Opéra (1829–1849): A Study in Music Criticism.”<br />

Ph.D. dissertation, New York Univeristy (1973).<br />

5 H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong>, “Bob Dylan: His Generation and his Protest.” Les langues modernes 66, 1<br />

(1972): 73–78.<br />

6 H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong>, Les Gravures musicales dans L’Illustration de 1843 à 1899. 3 vols. (New York:<br />

Pendragon Press, 1982–83).<br />

7 H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> and Marie-Odile Gigou. Cent ans de mise en scène lyrique en France (env.<br />

1830–1930) = One Hundred Years of Operatic Staging in France: Catalogue descriptif des livrets de<br />

mise en scène, des libretti annotés et des partitions annotées dans la Bibliothèque de l’Association de la<br />

régie théâtrale (Paris). La vie musicale en France au XIXe siècle 2 (New York: Pendragon Press,<br />

1986). H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> and Marie-Odile Gigou. The original staging manuscripts for twelve<br />

Parisian operatic premieres = Douze livrets de mise en scène lyrique datant des créations parisiennes.<br />

La vie musicale en France au XIXe siècle 3 (Stuyvesant, N.Y.: Pendragon Press, 1991).<br />

14

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

1982 International Musicological Society conference, a panel was convened<br />

on French archives and archival sources for the music historian; this collection<br />

of essays, compiled and introduced by <strong>Cohen</strong>, was published in 19th Century<br />

Music. 8 Following his appointment to the faculty of the University of British<br />

Columbia in Vancouver, he founded the Center for Nineteenth Century<br />

Music Studies to facilitate research in this growing domain.<br />

* * *<br />

<strong>Cohen</strong>’s magnum opus is RIPM, Le Répertoire International de la Presse Musicale.<br />

Established in 1980, RIPM’s genesis can be found in his experiences as<br />

a graduate student. As a member of a generation of scholars who sought to reimagine<br />

nineteenth-century musical studies through a richer, contextualized,<br />

granular, and international perspective—contra that which was handed down<br />

by the largely-German founding fathers of the discipline—a great amount<br />

of foundational work was required: to develop bibliographies, establish basic<br />

historical facts, gauge critical reception, record repertory, identify performers<br />

and performances, locate biographical information … in short, to document<br />

and understand the vast milieu of nineteenth-century musical life. For this,<br />

the musical press was vital—where else could one so completely immerse oneself<br />

in contemporary musical life, to view musical history through the eyes<br />

of those who lived it? Yet, here he sat in the reading room of the Bibliothèque<br />

National in Paris, taking a volume off the shelf, turning hundreds of pages,<br />

making notes, and returning it back to the shelf for the next researcher to<br />

come along, take the same volume off the shelf and turn the same hundreds of<br />

pages. He has often remarked about the seeming absurdity of this: In an era<br />

of networked computers and space travel, how could one still rely upon such<br />

ancient and inefficient methods?<br />

The foundation of RIPM came at a fortuitous time. A burgeoning scholarly<br />

interest in the nineteenth-century press, demonstrated through such projects<br />

as the Waterloo Directory of Victorian Periodicals, the Wellesley Index to Victorian<br />

Periodicals, and the Bibliographie des revues et journaux littéraires des XIX e et XX e<br />

siècles provided points-of-departure. At the same time, the value of computer<br />

technology and its application in the humanities had been validated through<br />

an increasing number of projects, most relatedly in Barry S. Brook’s Réper-<br />

H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong>, Dix livrets de mise en scène lyrique datant des créations parisiennes, 1824–1843 =<br />

The Original Staging Manuals for Ten Parisian Operatic Premières, 1824–1843. La vie musicale en<br />

France au XIXe siècle 6 (Stuyvesant, N.Y.: Pendragon Press, 1998).<br />

8 19th-Century Music 7, no. 2 (1983).<br />

15

Introduction<br />

toire International de la Littérature Musicale (RILM) which began producing<br />

indexes to current music literature via a IBM S360 mainframe computer<br />

in 1967. Although calls for retrospective indexing of music periodicals had<br />

existed since the 1930s, the scope of the challenge—thousands of journals,<br />

published in dozens of languages, totaling millions of pages—made such a<br />

project nearly impossible before the computer age.<br />

After a proposal to the board of the International Association of Music<br />

Libraries, Archives, and Documentation Centres (IAML) in 1980, RIPM was<br />

officially approved one year later; approval by the IMS followed in 1983. The<br />

foundational years of RIPM—ca. 1981 to 1987—were consumed by the innumerable<br />

tasks required to begin such a large-scale project: Indexing norms<br />

were debated and formalized through a Commission Mixte; selection of the<br />

journals for priority indexing was made; networks of collaborators and supporters<br />

were established; staff at the Center for Nineteenth Century Music<br />

Studies were hired and managed; a parallel center, the Centro internazionale<br />

di ricerca sui periodici musicali (CIRPM) in Parma and directed by Marcello<br />

Conati, was created; computer applications for data input and indexing were<br />

written; arrangements with a publisher, UMI of Ann Arbor, Michigan, were<br />

made; publisher’s advertising materials were created; initial data samples were<br />

input, edited, and revised; methods for printing and generating camera-ready<br />

copy were devised; publication of an annual journal, Periodica musica, on bibliographic<br />

and research problems concerning the musical press, was initiated;<br />

and perhaps most importantly, the funding for all of these initiatives was<br />

secured. After all, even with the best of intentions, hard-working colleagues,<br />

and expectant scholars, a project cannot be successful without funds to pay for<br />

everything from salaries to equipment to trash collection. In this, <strong>Cohen</strong> was<br />

incredibly successful: RIPM’s twenty-four consecutive years of funding from<br />

the National Endowment for the Humanities, five grants from the Andrew<br />

W. Mellon Foundation, many years of support from UNESCO’s International<br />

Council on Philosophy and Humanistic Studies, and numerous grants and<br />

subventions from European universities and musical societies demonstrated<br />

the scholarly importance of RIPM, yes, but also proved <strong>Cohen</strong>’s dogged determination<br />

that RIPM should succeed.<br />

Finally, in 1988—after moving the Center for Nineteenth Century Music<br />

Studies to the University of Maryland—the first RIPM publications appeared.<br />

Naturally, these treated two French journals: La Chronique musicale<br />

(Paris, 1873–1876) and L’Art musical (Paris, 1860–1894). Titles in German,<br />

English, and Italian followed quickly with a promised publication plan of<br />

ten volumes per year. In the subsequent reviews, scholars widely praised the<br />

16

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

project: “an essential stepping-stone into the riches of nineteenth-century<br />

periodical literature” (Music & Letters), “should be on the reference shelves of<br />

every major library” ( Journal of the American Musicological Society), “The excellence<br />

of this worthwhile project is beyond doubt” (Times Literary Supplement). 9<br />

Regarding the promised publication schedule and scope, Robert frequently<br />

recounts—with pride—that at the 1987 IMS meeting in Bologna and Parma,<br />

one distinguished scholar pronounced that Robert “was nuts” to attempt<br />

something so ambitious.<br />

In the 1990s, with the addition of Christoph-Helmut Mahling’s research<br />

center at the Johannes-Gutenberg Universität in Mainz, these production goals<br />

were continually met. This decade saw the creation of new RIPM groups in<br />

Scandinavia, Poland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Russia, and Portugal, with<br />

additional indexing carried out at the International Center in Maryland. By<br />

1998, RIPM had achieved its initial goal, namely, one hundred volumes in ten<br />

years, a rate of production noted by multiple NEH reviewers, one of whom<br />

described it as “a dream of productivity that is virtually unprecedented in the<br />

field of musical scholarship.” 10<br />

With the dawn of the new millennium, Robert laid the groundwork for a<br />

wholesale transformation of RIPM in the coming two decades. First, RIPM<br />

became incorporated as a federally-approved not-for-profit organization and<br />

RIPM’s offices were relocated to Baltimore, achieving financial and administrative<br />

independence. Concurrently, after one decade with the publisher<br />

UMI, Robert negotiated a new contract with the Baltimore-based publisher<br />

NISC, thereby beginning RIPM’s entry into online distribution. In 2000, the<br />

RIPM Retrospective Index to Music Periodicals Online first appeared on NISC’s<br />

Biblioline service. Additional online distributors would be added in the next<br />

decade, including OCLC’s FirstSearch, EBSCO’s EBSCOHost, and Ovid’s<br />

SilverPlatter. 11<br />

However, the usefulness of an index to source material is certainly dependent<br />

upon one’s access to the sources cited. Since scholars “rediscovered”<br />

the wealth of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century musical press, three issues<br />

prevented its wider study and application in scholarship, namely (i) which<br />

journals were important, both for general musical information and specialized<br />

studies; (ii) how and where can one quickly access a copy of the journals<br />

sought; and (iii) how does one locate content within thousands of pages, if no<br />

9 Music & Letters 71, no. 1 (February 1990). Journal of the American Musicological Society 43, no. 3<br />

(Fall 1990). Times Literary Supplement (31 March – 6 April 1989).<br />

10 “Reviews.” https://ripm.org/?page=Reviews (accessed 24 February 2021).<br />

11 For more on the challenges and complexities of the world of scholarly databases, see Barbara<br />

Dobbs Mackenzie’s essay herein, “A Tale of Two R-Project Directors”: 501-11..<br />

17

Introduction<br />

index is available. By the early 2000s, RIPM had done much to solve the first<br />

problem, through publication of Periodica musica and the increased scholarly<br />

attention given to the musical press, and the last problem, through its continual<br />

indexing efforts which by circa 2005 had resulted in some one hundred<br />

fifty volumes published and 450,000 annotated citations online. The second<br />

problem remained largely unresolved. Although RIPM had jointly sponsored<br />

a preservation microfilming project with UMI in the 1990s, which made available<br />

a number of rare journals, the increasingly-widespread availability of the<br />

World Wide Web meant that one could search and read historic texts from<br />

one’s home or office at the speed of a click. 12 With an initial foundation laid by<br />

the efforts of JSTOR in the late 1990s, Robert began a study of best practices<br />

for digitization. With the support of two grants from the National Endowment<br />

for the Humanities, the RIPM Online Archive of Music Periodicals debuted in<br />

2009. In order to meet the project’s need for original source copies, RIPM created<br />

a Partner and Participating Libraries program which has allowed RIPM to<br />

scan millions of pages from dozens of major libraries ranging from the Library<br />

of Congress to the Moscow Conservatory, and the Cenidim in Mexico City to<br />

the Eastman School of Music’s Sibley Music Library. 13 RIPM created an onsite<br />

scanning laboratory, scanning equipment for use offsite in libraries, developed<br />

a robust IT infrastructure, established hosting servers and all of the associated<br />

technological requirements, too numerous to list.<br />

Development of RIPM’s digitization efforts coincided with a consolidation<br />

amongst RIPM’s online distributors following the financial crisis of<br />

2008. As such, Robert advocated for the creation of RIPM’s own online<br />

delivery platform which came to be known as RIPMPlus. The creation of<br />

this platform—and the flexibility and control it offered to RIPM—laid the<br />

groundwork for RIPM’s future digital initiatives. First, through its scanning<br />

operations, massive collections were made available to RIPM including many<br />

journals which ran for tens to hundreds of thousands of pages. The necessity<br />

of a project which could provide access to large quantities of journals,<br />

in complete runs, scanned and full-text searchable, without having to wait<br />

for indexing, became clear. Thus the RIPM Preservation Series was born—<br />

initially titled the RIPM Full Text Supplement, later the eLibrary of Music<br />

Periodicals—a project which continues to grow, approaching one million<br />

pages and billions of searchable terms.<br />

12 Certainly this is a fulfillment of Barry S. Brook’s “Gin and Tonic Phantasy,” as illuminated<br />

by Zdravko Blažeković’s essay herein. See “The Early Years of the Répertoire International<br />

d’Iconographie Musicale,” 353.<br />

13 A complete, up-to-date list of Parter and Participating Libraries is available on RIPM’s website,<br />

ripm.org.<br />

18

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

Since his youth in Baltimore where his uncle took Robert to jazz clubs,<br />

in his adolescence when he played saxophone in a band, and through his university<br />

years in 1960s New York, Robert has always been a jazz aficionado.<br />

Almost since RIPM’s inception, the large and vital jazz press had remained on<br />

RIPM’s desiderata list. Finally, in 2016 RIPM signed an agreement with the<br />

Institute for Jazz Studies at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, the<br />

famed jazz archive. Jazz periodicals represented a departure for RIPM: Not<br />

only was the musical genre entirely different from RIPM’s other journals, but<br />

these journals also presented new challenges related to copyright and rights<br />

holders. Nevertheless, in 2019 RIPM Jazz Periodicals debuted, allowing full<br />

text access for the first time to 105 journals which documented and discussed<br />

jazz’s development from 1914 to 2000. To say the project has drawn great<br />

interest and enthusiasm would be an understatement; as one reviewer noted,<br />

RIPM Jazz Periodicals stands to “revolutionize this field by giving jazz researchers<br />

a huge vocabulary of common source material.” 14<br />

* * *<br />

This narrative is necessarily reductive, compressing some forty years of labor<br />

into a few mere paragraphs. It lends the impression that success was inevitable.<br />

However, the labor required to establish scholarly networks, apply for and<br />

preserve funding, maintain production quality and quantity, obtain projectsustaining<br />

grants and subscriptions, hire capable staff … such are the pitfalls<br />

which bedevil many a well-intentioned academic project. Yet, thanks to Robert,<br />

RIPM succeeded.<br />

H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> is the last of the founding directors of the R-projects.<br />

As he often recalls, he came of scholarly age during the postwar generation of<br />

musicology, studying with Gustave Reese and taking the A train in New York<br />

with Barry S. Brook, founder of two R-projects himself. 15 This was an age<br />

where source studies were vital and central to musicology. Afterall, how can<br />

we say anything definitively as historians if we do not have control over the<br />

sources? But with new technologies, and with determination, we could gain<br />

control and thereby deepen our knowledge of musical history and to correct<br />

the received historical record. A “forgotten century” could be rediscovered.<br />

14 Carlos Peña, “RIPM Jazz Periodicals.” Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association<br />

(March 2020): 486–90.<br />

15 <strong>Cohen</strong> recalled this during a memorial session to Brook at the 2015 IAML-IMS Congress<br />

in New York. As Robert has noted, he only barely missed Curt Sachs, a great figure of<br />

prewar musicology in Germany, who began teaching at NYU in 1937 after emigrating from<br />

Germany.<br />

19

Introduction<br />

Robert proudly states that he chose his own path in musicology. When advised<br />

to pursue a traditional career path, which would have involved a faculty<br />

appointment at a large, likely American university, he chose to teach in Paris,<br />

Universitè Laval in Quebec City, and the University of British Columbia in<br />

Vancouver. When advised to pursue topics en vogue in 1960s musicology, he<br />

chose to work on Berlioz, the French nineteenth century, iconography and<br />

unexplored documentation sources. When advised to not involve himself in a<br />

career-consuming project, he chose to develop RIPM, a project on the musical<br />

press, at that time a wild and uncontrolled realm. While all of this demonstrates<br />

a certain iconoclastic streak, the importance of primary sources for<br />

our understanding of musical history remained his central focus: the musical<br />

press, iconography, staging manuals, statuettes. Naturally, this is the focus of<br />

this volume: Musical History as Seen through Contemporary Eyes.<br />

* * *<br />

Reflective of Robert’s diverse interests, the contributions to this volume contain<br />

a number of themes, many of which overlap, and draw upon a range of<br />

source material.<br />

Naturally, the musical press plays a large role in this volume. Malena Kuss<br />

translates the distinguished Cuban musicologist and librarian Zoila Lapique<br />

Becali’s delightful and insightful study of nineteenth-century music in Cuban<br />

periodicals. Marten Nooduin offers an exploration of the reception history<br />

of the pianist cum conductor Charles Hallé via the mid-nineteenth century<br />

European press. Elvidio Surian identifies a lacuna in the study of Italian musical<br />

history in the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries, namely, sacred music<br />

journals. I uncover the unscrupulous and aggrandizing activities of the young<br />

editor and critic, John C. Freund, in the 1870s. Reflecting her copious work<br />

for RIPM on the nineteenth-century American musical press, Ruth Henderson<br />

transcribes and annotates the long-lost memoir of Max Strakosch, an important<br />

figure in nineteenth-century American musical life. Richard Kitson<br />

calls attention to a little-known figure in British music journalism, Ursula<br />

Greville, her merits as a writer and editor, and her struggles as a female in the<br />

male-dominated world of early twentieth century British music journalism.<br />

Antonio Baldassarre offers a significant study of the Nazi wartime journal<br />

Musik im Kriege and the German press culture from which it appeared, probing<br />

the relationship between music writing and the rise of repugnant politics.<br />

Berlioziana is naturally found here. Peter Bloom’s insightful and politically-probing<br />

essay on the historiography of Berlioz, drawn from two centenary<br />

20

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

celebrations of Berlioz’s birth, explores French attitudes toward the composer<br />

across more than a century. Catherine Massip explores Berlioz’s relationship<br />

to the town of Baden-Baden at the intersection of iconography and the<br />

nineteenth-century press. More broadly, music in France is explored in four<br />

papers: Joost van Gemert explores the transnational reaction to nineteenthcentury<br />

debates concerning the use of Gregorian chant in the French church.<br />

Allan Atlas uncovers two families in Paris and Brussels who performed upon,<br />

and promoted, the English concertina. Ralph Locke writes an appreciation of<br />

opérette via a recent recording of Andre Messager’s delightful Les p’tites Michu.<br />

John Roberts explores the compositional history of, and critical reaction to,<br />

the lesser-known Grands Opéras of Charles Gounod. Relating to both French<br />

musical bibliography and the R-projects, Jennifer Ward explores Marie Bobillier’s<br />

central importance to Robert Eitner in his Quellen-Lexikon catalog,<br />

the forerunner to the Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM).<br />

Bobillier, who wrote under the nom-de-plume Michel Brenet, demonstrated<br />

the problems faced by female music historians and bibliographers in the early<br />

twentieth century. Finally, reflecting Robert’s work on Giuseppe Verdi, Peter<br />

Sühring analyses Verdi’s sacred compositions, a lesser-explored area of Verdi’s<br />

oeuvre.<br />

Music iconography is explored in five papers, beginning with two on the<br />

scholarly history of the discipline. Zdravko Blažeković provides a history of the<br />

foundation and early years of the fellow R-project, the Répertoire International<br />

d’Iconographie Musicale (RIdIM). Florence Gétreau assesses the work of three<br />

founders of music iconography as a scholarly discipline in France. Luísa Cymbron<br />

provides us with a delightful exploration of visual depictions of sound<br />

transmission technologies in late-nineteenth century Lisbon. Frits Zwart explores<br />

the relationship between the conductors Willem Mengelberg and Leopold<br />

Stokowski via a photograph of Mengelberg leaving the cinema. Finally, Tatjana<br />

Marković analyses how sources—iconographical, textual, musical—define cultural<br />

memory through the publication of a single ballad.<br />

Jazz and popular music also make appearances. Reflecting Robert’s longstanding<br />

love of jazz, John Ehrenburg provides a reappraisal of pedagogical<br />

studies published in jazz periodicals, exploring the long-asked question of “how<br />

do you learn jazz?” Harkening back to Robert’s first published article, on Bob<br />

Dylan, Emile Wennekes muses on three cultural environments in which Robert<br />

is professionally and privately active: the United States, France, and the Netherlands,<br />

through three singer-songwriters within each national context.<br />

Finally, Barbara Dobbs Mackenzie offers us a glimpse into the “nanoniche”<br />

world of the R-project directors. As she astutely notes, directing an<br />

21

Introduction<br />

R-project requires one to draw upon a vast toolbox of skills, experience, and<br />

motivation; moreover it requires the ability to commit oneself to a project<br />

much bigger than an individual, traits demonstrated by Robert over the fortyyear<br />

span of RIPM.<br />

†<br />

We remember Katy Romanou (1939–2020), of the European University of<br />

Cyprus, who planned to contribute a paper on the vogue for philhellenic music<br />

in Paris during the 1820s, a decade which saw the premiere of Rossini’s Le<br />

siège de Corinthe (1826), Berlioz’s Scène héroïque (La révolution grecque) (1828) as<br />

well as vaudeville parodies, such as Le Dilettante, ou Le Siège de l’ Opéra (1826).<br />

As sung by Rossini’s chorus of Greek warriors, le destin trahit nos vœux. 16<br />

* * *<br />

This volume has been the product of so many labors. First, we offer sincere<br />

gratitude to all authors who submitted their valuable work and maintained<br />

patience with their overworked editors. A sincere thank you is owed to Elise<br />

Volkmann, former RIPM staff member, and current Ph.D. candidate at University<br />

of California, Berkeley, and many other members of the RIPM family,<br />

all of whose assistance proved invaluable. Michael Hüttler’s good cheer,<br />

Sigrun Müller's superb attention to detail, and the professionalism of all at<br />

Hollitzer Verlag made for a smooth production process. Finally, a very special<br />

thank you to those who wished not to be named but provided an extra set of<br />

eyes, advice, and help when called upon.<br />

Benjamin Knysak<br />

Baltimore, Maryland<br />

August 2021<br />

16 Gioacchino Rossini: Le siège de Corinthe. Libretto by Luigi Balocchi and Alexandre Soumet.<br />

Act I, introduction to scene 1.<br />

22

Musical Documentation of a “Forgotten Century” and Beyond<br />

THE MUSICAL PRESS<br />

23

24<br />

Introduction

A Ditty for a Friend: Honoring H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> through the Work of Zoila Lapique Becali<br />

A DITTY FOR A FRIEND:<br />

HONORING H. ROBERT COHEN THROUGH<br />

THE WORK OF ZOILA LAPIQUE BECALI (B. 1930),<br />

DOYENNE OF CUBA’S MUSICAL PRESS<br />

Malena Kuss<br />

University of North Texas (emeritus)<br />

I don’t remember when or where I met H. Robert, but it must have been in<br />

the 1980s, during the years I served as secretary of the International Association<br />

of Music Libraries’s Bibliography Commission and lectured frequently<br />

on matters bibliographical. Perhaps it was in Austin, in 1984, where I read a<br />

paper on “Music in Cuba: A survey of research resources” at a Music Library<br />

Association national meeting, or it could have been at the 1985 national meeting<br />

of the four societies in Vancouver, where I presented a paper on “Traditional<br />

elements in 19 th - and 20 th -century operas from Latin America and<br />

the Caribbean.” What I do know is that our first meeting was followed by a<br />

letter from H. Robert dated 16 August 1986, in which he asks me for Zoila<br />

Lapique Becali’s address to invite her to participate in a RIPM session at the<br />

forthcoming 1987 congress of the International Musicological Society (IMS)<br />

that was to take place in Bologna (Fig. 1). By then I had been advertising<br />

Zoila Lapique Becali’s extraordinary compendium, Música colonial cubana en<br />

las publicaciones periódicas, Tomo I (1812–1902), published in Havana by Editorial<br />

Letras Cubanas in 1979, which I had brought home from my first visit to Cuba<br />

in 1982. About the planned second volume of Música colonial cubana, Zoila<br />

Lapique Becali tells us the following in Cuba colonial: Música, compositores e<br />

intérpretes 1570–1902, the 2007 compendium that took its place: “The present<br />

book could have been the second volume of Música colonial cubana, published<br />

in 1979 by Editorial Letras Cubanas, but because of the many ideas explored<br />

during those intervening years, it took a life of its own.” 1<br />

I would like to think that I introduced H. Robert to this formidable figure<br />

in the field of print culture in Cuba. However, the invitation to Bologna did<br />

not materialize, because they met for the first time in Havana, on March 18,<br />

2014, at a session of all four Répertoires held during the first conference of the<br />

newly founded IMS Regional Association for Latin America and the Caribbe-<br />

1 Zoila Lapique Becali, Cuba colonial: Música, compositores e intérpretes 1570–1902 (La Habana:<br />

Publicaciones de la Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad—Ediciones Boloña, 2007), 9.<br />

25

Malena Kuss<br />

Fig. 1. Letter from H. Robert <strong>Cohen</strong> to Malena Kuss, 16 August 1986, concerning an invitation<br />

for Zoila Lapique Becali to the International Musicological Society Congress in Bologna.<br />

an that took place at Casa de las Américas March 17–21, 2014. A lovely photo<br />

of them (Fig. 2) engrossed in conversation documents the encounter of RIPM<br />

with the great music librarian who created her own version of writing history<br />

through the prism of the musical press.<br />

26