You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

B A C K S T O R Y<br />

06<br />

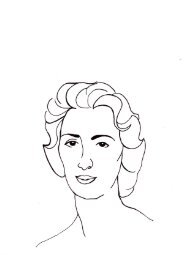

In the postwar years, with the rise of existential thought in<br />

Paris, Giacometti began making the tall, attenuated forms for<br />

which he is best known today. Although he often captured<br />

likenesses of specific individuals in busts (his brother Diego<br />

and his wife Annette were recurring subjects), he also<br />

produced sculptures of anonymous figures, as seen in his<br />

series of walking men and standing women. <strong>The</strong>ir elongated<br />

frames and roughly textured surfaces make them appear<br />

as stand-ins for humanity at large. Synthesizing figuration,<br />

Surrealism, and abstraction, they seem to reflect both on iconic<br />

images from antiquity and on the modern human condition.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se figures demonstrate what the existentialist philosopher<br />

Jean-Paul Sartre referred to as Giacometti’s “insistent<br />

search for the absolute.” In the catalogue preface for<br />

Giacometti’s 1948 exhibition at Pierre Matisse Gallery, Sartre<br />

wrote, “His ambiguous images disconcert, breaking as they do<br />

with the most cherished habits of our eyes. . . . do they come,<br />

we ask, from a concave mirror, from the fountain of youth, or<br />

from a camp of displaced persons?”<br />

More recently, in the <strong>2022</strong> exhibition catalogue Alberto<br />

Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate <strong>Figure</strong>, Catherine Grenier,<br />

director of Fondation Giacometti, stated, “He considered that<br />

the main role of art is to reflect reality, particularly through<br />

the image of the human body, but he did not hesitate pushing<br />

representation to its limits.” For the rest of his life, Giacometti<br />

continued testing those limits in his search for the absolute,<br />

creating and often destroying works in his efforts to distill the<br />

figure to its most essential elements.<br />

71 × 10 5/8 × 38 1/4”<br />

Man in Motion<br />

Giacometti’s Walking Man I (1960) derived from a commission for<br />

the plaza of the Chase Manhattan Bank in New York City. <strong>The</strong> artist<br />

conceived of a three-part installation, including bronze sculptures of<br />

a tall woman, a large head, and a walking man. However, he struggled<br />

with getting the proportions right. Unsatisfied with the results of<br />

his models, including this one, he withdrew from the project in 1961.<br />

Nevertheless, that same year Giacometti won the Carnegie Prize<br />

for this sculpture.