You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

THE<br />

MUSEUM<br />

O F<br />

FINE ARTS,<br />

HOUSTON<br />

MAGAZINE<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Figure</strong><br />

01

THE<br />

MUSEUM<br />

O F<br />

FINE ARTS,<br />

HOUSTON<br />

MAGAZINE<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Figure</strong><br />

Issue 23 / <strong>2022</strong><br />

02 Welcome<br />

04 Backstory<br />

08 Surfacing<br />

14 Object Lesson<br />

16 Portfolio<br />

26 Profile<br />

30 In the Mix<br />

38 Series<br />

02<br />

42 Up Close<br />

44 Five Minutes With<br />

46 Exhibition Funders<br />

47 Credits<br />

48 Coming Soon

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Figure</strong><br />

Depictions of the figure can be traced across millennia of human history,<br />

from the fertility talisman popularly known as the Venus of Willendorf,<br />

which has been dated back as far as 23,000 BCE, to Ron Mueck’s closely<br />

observed Woman with Shopping, created in 2014. This coming season,<br />

the Museum’s exhibition schedule offers a rich array of works addressing<br />

the figure throughout the ages, from the diminutive gold figurines of<br />

ancient American cultures seen in Golden Worlds: <strong>The</strong> Portable Universe<br />

of Indigenous Colombia, to the hauntingly attenuated personages of Alberto<br />

Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate <strong>Figure</strong>, to the deeply personal meditations<br />

on self and society explored in Philip Guston Now.<br />

01<br />

105 1/2 × 12 7/8 × 19 3/4”

G A R Y T I N T E R O W , D I R E C T O R<br />

T H E M A R G A R E T A L K E K W I L L I A M S C H A I R<br />

T H E M U S E U M O F F I N E A R T S , H O U S T O N<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Figure</strong><br />

W E L C O M E<br />

02<br />

Each approx.:<br />

74 5/8 × 45 5/8 × 7 3/8”<br />

It seems that every few decades a startling discovery is made that pushes the earliest<br />

evidence of art-making even further back in time. For years, the Venus of Hohle Fels, some<br />

35,000 years old, was regarded among the earliest surviving sculptural representations<br />

of the human figure; now, that distinction belongs to the Lion Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel,<br />

most likely made by a member of our species, Homo sapiens, about 40,000 years ago.<br />

No doubt other exciting finds will emerge, and advancing technology will provide more<br />

accurate dating of these fascinating objects.<br />

While the dates of the oldest artistic objects continue to be a matter of debate (some<br />

refined utensils are said to be more than 100,000 years old), so too the identities of the<br />

makers are hotly contested. If there is a consensus to be observed, it may be that one<br />

of the defining characteristics of modern humanity is the making of art. Early depictions<br />

feature animals, creatures that provided the essentials of life, food, and clothing, but they<br />

were inevitably paired with representations of humans, sometimes given animal anatomy<br />

in order to visualize supernatural beings.<br />

As we see in the rich compendium provided by this issue of h Magazine, figural representation<br />

has been a constant, perhaps the constant, obsession of artistic creation. <strong>The</strong><br />

pleasure that we enjoy and the thoughts that are launched when contemplating these<br />

objects are most certainly the raison d’être of art, which is a deeply rooted function, and<br />

a defining feature, of our humanity.<br />

Yours sincerely,

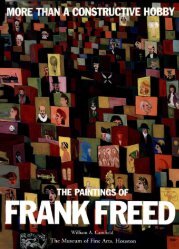

A <strong>Figure</strong> Revisited<br />

Primarily known for his paintings, Henri Matisse (1869–1954) broke with<br />

sculptural conventions with Back I–IV. Unusually focused on the back<br />

of a figure and created over two decades, from 1909 to about 1930, this<br />

sequence is best understood as one sculpture reconceived over time,<br />

tracing Matisse’s shift from naturalism to reductive abstraction.<br />

03

04

<strong>The</strong> exhibition Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate <strong>Figure</strong>, co-organized by the Fondation<br />

Giacometti in Paris and the Cleveland Museum of Art, will be presented in the Upper Brown Pavilion<br />

of the Caroline Wiess Law Building from November 13, <strong>2022</strong>, through February 12, 2023.<br />

Toward<br />

the Ultimate<br />

<strong>Figure</strong><br />

“<strong>Figure</strong>s were never for me a compact mass but like a transparent construction,”<br />

wrote the Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966) to his New York<br />

gallerist Pierre Matisse in 1947. <strong>The</strong> figure—and how to approach it—was<br />

a lifelong concern of the artist’s. Looking back on his career to that date,<br />

Giacometti explained the evolution of his artistic process to Matisse. He had<br />

produced his first bust in 1914 and had continued to work from models and<br />

draw from nature while studying at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière 05<br />

in Paris.<br />

After graduation, he began producing Cubist-inflected works. Rather<br />

than using live models, Giacometti shifted to working from memory and<br />

23 3/4 × 19 1/8”<br />

from his imagination. <strong>The</strong> symbolic qualities of the sculptures that he made<br />

during that time led him to be associated with the Surrealists from 1930 to<br />

1935. He ultimately broke with the group when he decided to return to using<br />

live models. However, Giacometti remained unsatisfied with the results, and<br />

by 1940 he once again determined to work from memory. He wrote, “<strong>The</strong><br />

sculptures became smaller and smaller . . . often they became so tiny that<br />

with one touch of my knife they disappeared into dust. But head and figures<br />

seemed to me to have a bit of truth only when small. All this changed a little<br />

in 1945 through drawing. This led me to want to make larger figures, but then<br />

65 × 6 1/2 × 13 1/2”<br />

to my surprise, they achieved a likeness only when tall and slender.”<br />

B A C K S T O R Y<br />

Taking a Stand<br />

<strong>The</strong> tall standing women that frequently recur in Giacometti’s oeuvre<br />

bring to mind ancient Egyptian pharaonic statues. Femme debout<br />

(Standing Woman; Tall <strong>Figure</strong>) (1948–49) is from Giacometti’s early foray<br />

into the form. He had initially created erect female figures at a small<br />

scale, but they began to grow in size in the immediate postwar period.<br />

This example stands more than five feet tall. Although life-size in height,<br />

the woman appears otherworldly due to her exceedingly slender build.

B A C K S T O R Y<br />

06<br />

In the postwar years, with the rise of existential thought in<br />

Paris, Giacometti began making the tall, attenuated forms for<br />

which he is best known today. Although he often captured<br />

likenesses of specific individuals in busts (his brother Diego<br />

and his wife Annette were recurring subjects), he also<br />

produced sculptures of anonymous figures, as seen in his<br />

series of walking men and standing women. <strong>The</strong>ir elongated<br />

frames and roughly textured surfaces make them appear<br />

as stand-ins for humanity at large. Synthesizing figuration,<br />

Surrealism, and abstraction, they seem to reflect both on iconic<br />

images from antiquity and on the modern human condition.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se figures demonstrate what the existentialist philosopher<br />

Jean-Paul Sartre referred to as Giacometti’s “insistent<br />

search for the absolute.” In the catalogue preface for<br />

Giacometti’s 1948 exhibition at Pierre Matisse Gallery, Sartre<br />

wrote, “His ambiguous images disconcert, breaking as they do<br />

with the most cherished habits of our eyes. . . . do they come,<br />

we ask, from a concave mirror, from the fountain of youth, or<br />

from a camp of displaced persons?”<br />

More recently, in the <strong>2022</strong> exhibition catalogue Alberto<br />

Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate <strong>Figure</strong>, Catherine Grenier,<br />

director of Fondation Giacometti, stated, “He considered that<br />

the main role of art is to reflect reality, particularly through<br />

the image of the human body, but he did not hesitate pushing<br />

representation to its limits.” For the rest of his life, Giacometti<br />

continued testing those limits in his search for the absolute,<br />

creating and often destroying works in his efforts to distill the<br />

figure to its most essential elements.<br />

71 × 10 5/8 × 38 1/4”<br />

Man in Motion<br />

Giacometti’s Walking Man I (1960) derived from a commission for<br />

the plaza of the Chase Manhattan Bank in New York City. <strong>The</strong> artist<br />

conceived of a three-part installation, including bronze sculptures of<br />

a tall woman, a large head, and a walking man. However, he struggled<br />

with getting the proportions right. Unsatisfied with the results of<br />

his models, including this one, he withdrew from the project in 1961.<br />

Nevertheless, that same year Giacometti won the Carnegie Prize<br />

for this sculpture.

A Head for <strong>Figure</strong>s<br />

Giacometti produced portrait busts of a few family members and<br />

friends throughout his career. His final male model was Eli Lotar, a<br />

Romanian filmmaker and photographer whom he had known since<br />

the 1930s, when they both associated with the Surrealists group.<br />

Lotar had since fallen on hard times, but Giacometti elevated him in<br />

a series of three busts, including this one, Bust of a Man (Lotar II),<br />

made in the final years of the artist’s life.<br />

07<br />

22 3/4 × 15 3/8 × 9 7/8”

<strong>The</strong> works shown here are among those featured in Golden Worlds: <strong>The</strong> Portable Universe of<br />

Indigenous Colombia, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts,<br />

Houston, and the Museo del Oro of Banco de la República, Bogota, on view November 6, <strong>2022</strong>, through<br />

April 16, 2023, in the Art of the Indigenous Americas Galleries of the Caroline Wiess Law Building.<br />

Figuring and<br />

Adorning the Body<br />

in Ancient Colombia<br />

BY REX KOONTZ<br />

CONSULTING CURATOR OF ANCIENT AMERICAN ART<br />

<strong>The</strong> Indigenous people of Colombia produced some of the<br />

most finely crafted, deeply meaningful gold art objects in<br />

the Americas before the coming of the Spanish. Much of this<br />

exquisite metalwork represented or was meant to be worn<br />

on the body—or, at times, both. While seemingly straightforward,<br />

the relationship between art and the human figure is<br />

complicated by Indigenous ideas about the body, gold, and<br />

representation. In Indigenous traditions, gold is believed to<br />

transform its wearer. This power of transformation, rather than<br />

the exchange value of gold as money, was the concept that<br />

drove Indigenous creations in gold.<br />

To understand the European relationship to the Indigenous<br />

tradition of goldwork, many may recount the story of El Dorado,<br />

the fabled city of gold. <strong>The</strong> idea of a golden city galvanized<br />

many European explorers of the 16th century, among them<br />

Sir Walter Raleigh and a number of Spanish conquistadors.<br />

For the Indigenous South Americans of this time, however,<br />

El Dorado referred not to a city but to a man—one who was<br />

sanctified through a covering of gold dust and then bathed in<br />

the waters of a sacred lake. <strong>The</strong>se Native people believed that<br />

the beauty and splendor of goldwork was intimately tied to its<br />

role in sanctifying the human body. Through this ceremony<br />

and the wearing of the gold, the Indigenous South Americans<br />

believed a man was transformed into a powerful ruler.<br />

<strong>The</strong> works shown here, drawn from the Glassell Collection<br />

at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, demonstrate the significance<br />

and transformative power of gold in relation to the human<br />

figure in Indigenous culture before the arrival of Europeans.<br />

This pectoral (opposite), or chest ornament, is a superb<br />

example of the Calima style, one of the most complex and<br />

celebrated of ancient Colombian metalwork. This type of<br />

pectoral was made throughout the southwestern part of the<br />

country, from about 100 BC to AD 800. Scholars agree that<br />

these pectorals, when taken as a group, are some of the largest<br />

and most impressive gold objects made by ancient Colombian<br />

artists. <strong>The</strong> combination of a central raised relief and the more<br />

delicate linear decoration on the outside border is typical of<br />

this object type, but the example seen here is particularly<br />

well realized.<br />

A human face forms the center of the composition. Creating<br />

this face was a two-step process: the face was first sculpted in<br />

a hard material, probably a hardwood or stone; then, a flat<br />

sheet of gold was pressed onto the sculpture, creating a raised<br />

impression of the face on the sheet of metal.<br />

<strong>The</strong> raised face is adorned with nose and ear ornaments,<br />

imitating in miniature the gold ornaments worn by important<br />

Indigenous leaders. <strong>The</strong> nose ornament was fashioned from a<br />

single gold sheet in an inverted I-shape, with lightly embossed<br />

decoration. <strong>The</strong> ear ornaments were not adorned with such<br />

designs, however, allowing the viewer to focus on their perfect<br />

geometry.<br />

<strong>The</strong> central face is a highly conventionalized figure that is<br />

repeated throughout Calima art. Scholars have suggested that<br />

the figure could depict a god or an ancestor. While the central<br />

face follows the traditional model seen throughout Calima<br />

art, the geometric designs on the outer border are unique to<br />

S U R F A C I N G<br />

09<br />

8 3/4 × 11 × 1 1/8”

S U R F A C I N G<br />

10<br />

4 1/8 × 2 × 1/2”<br />

this piece. In this instance, an artist embossed a series of<br />

curvilinear designs filled with hatched parallel lines. <strong>The</strong> pattern<br />

flows gracefully around the outer edge and frames the standardized<br />

central motif of the face.<br />

One can envision this pectoral on the chest of an Indigenous<br />

Colombian leader engaged in a key speech or dance some<br />

1,500 years ago. <strong>The</strong> leader’s head would have been surrounded<br />

in gold, with the pectoral below, both ears decked in large gold<br />

earspools, a nose ornament in the center of the face, and a<br />

golden crown on the forehead. <strong>The</strong> pectoral’s central face would<br />

have echoed, on a smaller scale but in a brilliant metal, the shape<br />

and adornment of the leader’s head just above. In this way, the<br />

Indigenous leader may have attained some sort of identity, or<br />

even union, with the being represented by the standardized<br />

face in the center of this pectoral.<br />

Gold was believed to contain the primordial energy of the sun,<br />

and therefore a leader who wore gold was thought to capture<br />

and channel the sun’s energy. This deeply Indigenous way of<br />

thinking, which sees value not in the material but in its relation to<br />

nature, also best explains the love of Indigenous Colombians for<br />

tumbaga (gold/copper alloys). In such alloys, the yellow color of<br />

gold, associated with the sun and viewed as male, is balanced<br />

by the reddish hue of copper, associated with female energies.<br />

This balance between male and female principles is highly<br />

valued in Indigenous thought. For this reason, much of the<br />

finest ancient Colombian work is not in gold but in gold/<br />

copper alloys that appear slightly reddish gold.<br />

Unlike the pectoral, which was clearly made to be worn, the<br />

function of this Seated Shaman <strong>Figure</strong> (at left) may not be as<br />

readily apparent. It was cast as a single piece, without the later<br />

addition of wire filigree. <strong>The</strong> highly conventionalized geometry<br />

of the form runs counter to the more supple naturalism seen in<br />

many ancient Colombian works over the previous millennium.<br />

Seated figures such as this one represent the thoughtful<br />

leader who, through ritual and considered action, becomes<br />

the center of the cosmos, balancing forces for the good of the<br />

people. <strong>The</strong> objects are called tunjos, although this name likely<br />

was only given to these pieces in the 19th century. <strong>The</strong>se types<br />

of figures are found in the region around Bogotá, the capital<br />

of Colombia, and were made by the Muiscas, the Indigenous<br />

peoples who inhabited that region when the Spanish arrived.<br />

When the Spanish first saw these figures in the 16th century,<br />

they called them santillos (little saints), associating them with<br />

Catholic saint figures—possibly hinting at their Indigenous<br />

meaning as small deity images. Like saints, these objects are<br />

intercessors with key sacred forces. Yet, these statuettes were

not meant to be seen by human eyes—only the gods were<br />

meant to witness them. <strong>The</strong>y were often found in groups as<br />

part of buried offerings near sacred places such as lakes,<br />

streams, and caves.<br />

<strong>The</strong> seated figure was constructed using the lost-wax casting<br />

method, which consists of laying down a fine sheet of wax for<br />

the body, then adding even finer strands of wax for the linear<br />

elements around the face and arms. <strong>The</strong> artist would then<br />

construct a mold of some more fire-resistant material and heat<br />

it so that the wax would drain out of the mold, to be replaced by<br />

the molten metal that retains the form of the wax. This technique<br />

produced the distinctly schematic body. Although these linear<br />

elements appear to be filigree (wire added later), they were<br />

actually cast using thin strands of wax. <strong>The</strong> human body is<br />

here a geometric figure formed by the artist out of a wax sheet,<br />

to which the linear elements defining appendages and facial<br />

features were added, also as wax elements. <strong>The</strong>re is little<br />

interest in the three-dimensional human body, as seen in the<br />

pectoral on page 8; instead, it is as if the wax serves as a sheet<br />

on which to write a message to the gods through the controlled<br />

geometric forms and linear patterns of this figure, which are<br />

similar to any number of other tunjos from this region and period.<br />

<strong>The</strong> seated figure is an example of a key theme in Indigenous<br />

Colombian goldwork: the presentation of authority. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

were two great postures of authority and power in these<br />

ancient Indigenous societies: one was the seated figure on a<br />

chair or bench, as in the Muisca figure on page 10, and the<br />

other is a figure seated on the floor, with hands around<br />

knees (at right). For both, the posture, rather than the elements<br />

of the human body, is what mattered to the artist; often the<br />

rest of the body is indicated with the barest of elements. In this<br />

example, the artist focused on melding the human form and<br />

the basket. <strong>The</strong> baskets that served as models were woven<br />

with plant fibers. <strong>The</strong> associated Indigenous metaphor relates<br />

the weaving of baskets with plant fibers to the human being<br />

who is woven with thought—the human is transformed into a<br />

receptacle of knowledge. <strong>The</strong> basket-body indicates that the<br />

human is ready to receive and gather the world’s wisdom.<br />

Like the Muisca Seated Shaman <strong>Figure</strong>, the human body<br />

depicted on page 12 is registered mainly in two dimensions—<br />

as no more than a gold sheet. In this Malagana (southwest<br />

Colombia) figure, the artist stresses the outer contours, leaving<br />

the interior of the body largely without detail. <strong>The</strong> overall effect<br />

is of a paper-thin cutout. <strong>The</strong> amount of skill necessary to<br />

hammer the gold into such a fine sheet is one of the central<br />

accomplishments of the artist. After the sheet was hammered<br />

flat, it was then a matter of cutting it with a firm hand to<br />

create the conventionalized frontal figure. A few lines<br />

were embossed to indicate hands and feet, but the<br />

visual interest is in the body’s contour. <strong>The</strong> only exception<br />

is the area of the face, where the artist has gone to<br />

greater lengths in indicating the eyes, nose, ears, and mouth<br />

and teeth.<br />

<strong>The</strong> function of this thin golden man remains obscure.<br />

<strong>The</strong> piece may have been placed in a burial alongside or on<br />

the deceased, as most gold objects were in this region.<br />

Unlike the majority of other Indigenous Colombian gold items,<br />

these thin men and other Malagana grave goods have no wear<br />

patterns that indicate they were used in life; rather, they seem<br />

to have been made specifically for burial. How these objects<br />

served the dead in the afterlife remains a mystery and is<br />

a reminder that there is still much to discover about these<br />

ancient peoples and their art.<br />

<strong>The</strong> diadem on page 13 would have been worn on the forehead<br />

of a leader or other key figure as part of a headdress. <strong>The</strong><br />

combination of the three-dimensional face and surrounding<br />

embossed linear decoration recalls the Calima pectoral, and<br />

indeed this piece is in the same style. Once again, the standardized<br />

face, already seen in the pectoral, appears in the<br />

center of the composition. <strong>The</strong> background figure, formed by<br />

the curvilinear contour lines, is a conventionalized bird flying<br />

downward. <strong>The</strong> emphasis on the descending bird’s tail recalls<br />

the importance and value of brightly colored tail feathers in<br />

11<br />

Approx.<br />

1 7/8 × 1 7/8” diam.

12<br />

15 1/2 × 8 1/2”

elite costume in Indigenous Colombia and throughout the<br />

Americas. <strong>The</strong> diadem connects the resplendent, solar nature<br />

of gold with the equally resplendent—and equally valued—<br />

iridescent feathers, which were also associated with the sky.<br />

<strong>The</strong> gold and feathers worn by the ruler were seen to physically<br />

transform the human ruler into a flying being. Wearing golden<br />

jewelry and feathers allowed the rulers to ascend to the sky<br />

realm and interact with celestial powers. Often this interaction<br />

was to maintain the balance and mutual respect between<br />

humans and nature necessary for life to thrive.<br />

Unlike much of the art that derives from Europe, Indigenous<br />

Colombian art traditions do not focus on the beautiful propor-<br />

tions or ideal facial features of the human figure. Indigenous<br />

jewelry was intended not to represent or decorate the human<br />

body but to transform it. This transformation inserted the<br />

human more intimately into nature, as when the sun’s energy<br />

was captured by an artist working in gold so that an Indigenous<br />

ruler could become one with the sky animals (resplendent<br />

birds) and with the power of the sun itself. <strong>The</strong> objects seen<br />

here—and several others in the Glassell Collection—<br />

celebrate the brilliance of fine goldwork while situating the<br />

power of gold firmly in larger Indigenous ideas of humans and<br />

their relation to nature.<br />

S U R F A C I N G<br />

13<br />

10 1/4 × 9 1/8 × 3/4”

Model into Myth<br />

BY JAMES CLIFTON<br />

DIRECTOR, SARAH CAMPBELL BLAFFER FOUNDATION,<br />

AND CURATOR OF RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PAINTING<br />

<strong>The</strong> Roman poet Ovid and other ancient writers told the story<br />

of Marsyas, a satyr who was skinned alive by the god Apollo.<br />

Having learned to play a wind instrument discarded by the<br />

goddess Minerva, Marsyas foolishly challenged Apollo to a<br />

musical contest and lost both the contest and his life. <strong>The</strong><br />

violent subject was a favorite among Renaissance artists.<br />

Dirck van Baburen (1595–1624), one of the most prominent<br />

painters in the Dutch city of Utrecht, depicted the subject at<br />

nearly life-size in the early 1620s, either toward the end of his<br />

long sojourn in Rome or soon after he returned to Utrecht.<br />

In Van Baburen’s painting, Marsyas—human in form aside<br />

from a single visible horn—lies supine on a stone block. He<br />

screams as Apollo, his golden head wreathed with laurel of<br />

Parnassus and his mantle “dipped in Tyrian dye,” as described<br />

by Ovid, slices Marsyas’s shin with something akin to a scalpel<br />

in his right hand, pulling the skin away with his left. In the background<br />

at right, three figures—two visibly horned like Marsyas<br />

and wearing ivy crowns—wail in dismay.<br />

Van Baburen draws a clear distinction between the two main<br />

figures. Apollo, seen in profile, virtually expressionless, stably<br />

positioned, and tightly composed within a closed silhouette,<br />

recalls classical relief sculpture and its Renaissance derivations.<br />

Marsyas, conversely, lies precariously upside-down,<br />

arms and legs akimbo, his face contorted. Though the story<br />

does not call for Marsyas to be flayed upside-down, several<br />

artists used the motif, which, as in other contexts, expresses<br />

the utter helplessness of the victim. Many interpretations<br />

of the myth and its representations depend on the contrast<br />

between Apollo and Marsyas—for instance, between beauty<br />

and ugliness, order and disorder, and wisdom and foolishness.<br />

Van Baburen uses the subject as a demonstration of the<br />

human anatomy and his ability to represent it. With a strong<br />

play of light and shadow, typical of the Caravaggesque style<br />

of the early 17th century, he sculptures the figures’ powerful<br />

physiques, particularly their muscular shoulders. A further<br />

characteristic of this style is a close observation of reality.<br />

Marsyas, single horn notwithstanding, looks like a model in<br />

the studio: a low posing platform has been transformed into a<br />

block that has no function in the narrative, and a rope probably<br />

used to suspend the model’s leg is here tied to a tree. Van<br />

Baburen proclaims his imitative skill, even if it compromises<br />

the narrative conventions of the story.<br />

<strong>The</strong> artist’s artifice in this carefully composed and executed<br />

painting turns the viewer’s attention to his skill and the interpretative<br />

possibilities of the subject. Aristotle recognized the<br />

pleasure to be had in looking at representations of things that<br />

might be disagreeable in actuality, and a contemporary of Van<br />

Baburen’s famously wrote about a painting of <strong>The</strong> Massacre of<br />

the Innocents “that often horror goes with delight.” In drawing<br />

attention to his artifice in this painting, Van Baburen elicits<br />

responses that may equivocate between visceral horror and<br />

critical appraisal.<br />

O B J E C T L E S S O N<br />

15<br />

75 5/8 × 63”<br />

In accordance with ancient and<br />

Renaissance philosophy, Apollo’s<br />

calm demeanor as he goes about<br />

his grisly task is in contrast to<br />

Marsyas’s passionate howl, just<br />

as the rational is to the irrational,<br />

and the human is to the bestial.<br />

<strong>The</strong> V-shaped tan below Marsyas’s<br />

throat, which follows the line of a<br />

shirt, indicates that Van Baburen<br />

painted the model as he must have<br />

appeared in his studio, rather than<br />

as a woodland creature accustomed<br />

to frolicking naked in the sunshine,<br />

as called for by the story.<br />

<strong>The</strong> three figures reacting in horror<br />

stand in for those Ovid said wept for<br />

Marsyas: peasants, sylvan deities,<br />

fauns, satyrs, and even the gods<br />

on Olympus.<br />

At the lower left, Apollo’s five-string<br />

lira da braccio lies atop Marsyas’s<br />

syrinx (panpipe), suggesting the<br />

god’s victory in their musical contest.

A C R O S S T H E C O L L E C T I O N S<br />

Go <strong>Figure</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Greek philosopher Aristotle believed “the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance<br />

of things, but their inward significance.” For millennia, artists have aimed not only to capture the figure but<br />

to infuse its representation with deeper meaning and purpose—whether to embody lived experience, to<br />

uphold tradition, or to examine its magical quality. <strong>The</strong> works shown here—all drawn from the Museum’s<br />

collection—comprise a cross-cultural snapshot of artists’ ever-evolving approach to and stylistic<br />

treatment of the figure.<br />

P O R T F O L I O<br />

16<br />

20 × 15 1/4 × 17 3/4”<br />

460–450 BC<br />

This monumental krater, an ancient<br />

Greek vessel for diluting wine, depicts<br />

several figures in composite engaged<br />

in a dramatic battle scene. A rider on<br />

a rearing mount fends off two soldiers,<br />

called hoplites, who peer over their<br />

decorated shields. One of the foot<br />

soldiers, wearing a Thracian helmet<br />

and a star-studded tunic, attempts a<br />

strike with his spear. Kraters were an<br />

important part of symposia, all-male<br />

banquets that featured wine, food,<br />

games, and entertainment. Such<br />

combat scenes were inspired by<br />

<strong>The</strong> Iliad, the poet Homer’s great<br />

war epic from the 7th century BC.

Modeled c. 1910<br />

<strong>The</strong> celebrated French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) is<br />

known for creating extraordinarily expressive figures and brilliantly<br />

exploiting materials and surfaces while conveying the physical,<br />

emotional, and even psychological aspects of his subjects.<br />

Throughout his career, Rodin often reused and reconceived certain<br />

figures for other contexts, including this half-length nude woman,<br />

which derives from his monumental Gates of Hell. Based on Dante’s<br />

Inferno, Rodin’s Gates of Hell, which comprises more than 200<br />

figures, occupied the sculptor for almost 40 years.<br />

17<br />

31 × 23 × 15”

18<br />

7 × 4 1/2 × 1 3/4”<br />

4 1/2 × 5 × 1 3/8”<br />

1500–500 BC<br />

This Japanese dogu, or clay figurine, depicts a<br />

heavily decorated person. <strong>The</strong> body shape is typical<br />

of the Final Jomon period (c. 1000–300 BC), but<br />

the headdress is markedly different—it consists of a<br />

circular headpiece topped by rectangular protrusions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> purpose of dogu remains a mystery: nearly all<br />

surviving examples are broken at the arms, legs,<br />

or waist, leading scholars to believe they were<br />

deliberately fragmented, possibly to heal the sick by<br />

releasing bad spirits. <strong>The</strong>y also speculate that these<br />

figures are wearing masks—possibly representing the<br />

transformation of the human into the superhuman.<br />

11th century<br />

Figural imagery is widely appreciated in the secular sphere of<br />

Islamic art. This handle or doorknocker fashioned in the form<br />

of a man was most likely placed in a secular setting like a private<br />

home. On the man’s clothes, gold and silver inlay create delicate<br />

knot-scroll motifs characterized by endless loops and dizzying<br />

geometric patterns.

Late 19th–early 20th century<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kota peoples used mbulu ngulu, reliquary guardian figures<br />

such as this one, to protect and mark the bones, especially the<br />

skull, of revered ancestors. <strong>The</strong> bones were placed with other<br />

relics of the deceased in a bark box or basket, with the figure<br />

atop. <strong>The</strong> elegantly designed visage features protruding circular<br />

eyes and a triangular nose, flanked by thin rays of metal. Such<br />

figures are iconic in African art, with the Kota examples being<br />

unique with the combination of wood and hammered metal.<br />

P O R T F O L I O<br />

19<br />

24 × 10 1/8 × 2 1/2”

Second half of the 13th century<br />

<strong>The</strong> crowned figure in this Iranian ewer<br />

holds a double-spouted water-skin from<br />

which the vessel’s contents would have been<br />

poured. <strong>The</strong> figurine’s dress is decorated<br />

with the renowned and enduring triple-dot<br />

motif. Together with the crown, these details<br />

indicate that this represents a royal figure.<br />

P O R T F O L I O<br />

20<br />

10 1/4 × 5 1/4 × 4 5/8”

21<br />

11 × 4 1/2 × 4 1/2”<br />

c. 1849–52<br />

This jaunty figure sports a long cloak that cleverly adapted the human form to the requisite<br />

bottle shape, while the top hat accommodated the cork. Production of Rockingham pottery,<br />

with its characteristic brown glaze, began in the United States in the 1830s and 1840s. Daniel<br />

Greatbach, whose grandfather had worked as a modeler for Josiah Wedgwood, worked first<br />

in New Jersey before moving to Bennington, Vermont. Among the objects he created there<br />

was this bottle modeled as a man. <strong>The</strong> form continued an English tradition of figural bottles<br />

for gin that local bars distributed to their clients.

22<br />

Sheet: 18 × 14”<br />

1911<br />

A protégé of Gustav Klimt, the Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele (1890–1918)<br />

was known for his graphic style and embrace of figural distortion. His erotic and<br />

deeply psychological portraits possess an idiosyncratic line and a selective use of<br />

color. In this watercolor, Girl in Red Robe and Black Stockings, Schiele portrays a<br />

provocatively dressed woman in an accentuated, twisting pose, isolated on a sheet<br />

of paper. Through the artist’s detached approach, she appears as an object for<br />

formal analysis. Yet Schiele’s artistic process was an intimate experience—to create<br />

his loose, fluid figurative sketches, the artist used a continuous drawing technique<br />

that required constant eye contact with his model.

P O R T F O L I O<br />

23<br />

14 1/4 × 15 × 13 3/4”<br />

1975<br />

<strong>The</strong> American ceramic artist Viola Frey (1933–2004) used colors and overglazes<br />

to give her dynamic figures an “alertness and vividness and to unfreeze them.” Her<br />

sculpture Esther Williams and Deborah Kerr at Pool is alive with painterly color,<br />

emotion, dappled light, and naturalism. Its subject matter can be traced to Frey’s<br />

childhood memories, but despite her admiration for these stars of Hollywood’s<br />

golden age, Frey renders them as real people, rather than as glamorous film icons.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir languid and abstracted limbs and simplistic faces deliberately project traces<br />

of the artist’s hand.

2014<br />

Ron Mueck (born 1958) draws upon memories,<br />

reveries, and everyday experience as he<br />

approaches his subjects with extraordinary<br />

empathy. Typically spending more than a<br />

year conceiving and making each figure,<br />

Mueck captures every physical detail with<br />

an astonishing degree of verisimilitude.<br />

This naturalism, however, is undercut by<br />

his calculated play with scale. Woman with<br />

Shopping, which stands only 44 inches high,<br />

was inspired by a woman and child Mueck<br />

spotted on a London street; he meticulously<br />

translated this fleeting encounter into a<br />

compassionate testament to new motherhood,<br />

and the loving care it demands.<br />

P O R T F O L I O<br />

24<br />

44 1/2 × 18 1/8 × 11 7/8”

25<br />

96 × 83 3/4 × 1/4”<br />

1995<br />

Jack Whitten (1939–2018) was among the vanguard of New York artists whose innovative<br />

approach to painting in the 1970s and 1980s emphasized the physicality of their canvases and<br />

materials. Whitten’s work stands out among his contemporaries, however, as he reconciled<br />

his formal explorations with nuanced meditations on history, science, and the nature of<br />

Black identity. Natural Selection features his autographic mosaic technique, with handmade<br />

blocks of acrylic paint creating a shimmering grid. At the same time, the shadowy figure gives<br />

the composition an emotive anchor, further buttressed by the title, which refers to Charles<br />

Darwin’s description of the struggle for existence.

Philip Guston Now, a retrospective featuring more than 110 paintings and drawings, will be on view from<br />

October 23, <strong>2022</strong>, through January 16, 2023, in the Brown Foundation, Inc., Galleries of the Audrey Jones Beck Building.<br />

Philip Guston:<br />

Living in a<br />

World Museum<br />

BY ALISON DE LIMA GREENE<br />

THE ISABEL BROWN WILSON CURATOR, MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART<br />

Over a career that spanned five decades, Philip Guston<br />

consistently explored different modes of representation, at<br />

times emulating the high polish of Renaissance art, at times<br />

subsuming his subjects in a dense web of brushstrokes, and<br />

at times describing the world around him with the anarchic<br />

spirit of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comics. Coming of age<br />

in Los Angeles, Guston (1913–1980) eschewed traditional<br />

fine-arts training, and by the early 1930s his political stance<br />

had been honed by news of the Scottsboro trials, brutal<br />

encounters with the Los Angeles Police Department’s<br />

notorious Red Squad, and Klan rallies. His first ambitious<br />

paintings—including a monumental mural created with<br />

Reuben Kadish in Morelia during the winter of 1934—<br />

drew on these experiences to confront racism and religious<br />

intolerance.<br />

Throughout the 1930s Guston was also honing his own<br />

identity. His parents were among the wave of Jewish emigrants<br />

who fled the pogroms that swept Central Europe at the turn<br />

of the 20th century, landing first in Montreal before making<br />

their way to Southern California in 1922. <strong>The</strong> family was<br />

broken apart by the suicide of Guston’s father, Leib Goldstein,<br />

the following year and by the accidental death of Guston’s<br />

brother Nat a decade later. In 1936 the aspiring artist cast off<br />

his birth name, changing Phillip Goldstein to Philip Guston, and<br />

left for New York, where he began a new life with the painter<br />

and poet Musa McKim.<br />

New York introduced Guston to a vital community of artists.<br />

Jackson Pollock, a friend from high school, first made him<br />

welcome, and Guston found employment through the Federal<br />

Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. He undertook<br />

a number of public commissions, including Work and Play<br />

for the Queensbridge Houses Community Center (1939–41);<br />

his painting Gladiators (1940, opposite) reprised a segment<br />

from that mural. Compressing the composition to its most<br />

essential features, Guston adroitly balanced his love of such<br />

paintings as Paolo Uccello’s Battle of San Romano (c. 1435–<br />

60) with his assimilation of Stuart Davis’s suave Modernism.<br />

<strong>The</strong> painting can also be understood as a metaphor for the<br />

larger conflict that was rapidly consuming Europe: four boys<br />

are locked in a tight Mobius strip of grasping hands, thrusts,<br />

and blows—their faces concealed, their weapons scavenged<br />

from the streets.<br />

Guston spent much of the 1940s teaching in Midwestern<br />

universities. Haunted by news of the Holocaust, he grappled<br />

with how to resolve his commitment to meaningful subject<br />

matter while also responding to new currents in American<br />

painting. After a 1948–49 sabbatical at the American<br />

Academy in Rome, he returned to New York and shifted<br />

into abstraction, explaining, “I wanted to come to a canvas<br />

and see what would happen if I put on paint.” However, the<br />

nonobjective, painterly compositions that placed him at the<br />

center of the Abstract Expressionist vanguard in the early<br />

1950s gave way to paintings imbued with hints of more<br />

concrete subject matter. For example, Painter (1959, see<br />

page 28) is characterized by the lush palette and gestural<br />

layering typical of his abstractions. At the center of the composition,<br />

a triangular scaffold suggests the outline of an easel,<br />

or even a Klansman’s silhouette harking back to Guston’s<br />

first paintings, while the red form at center top echoes the<br />

hood of one of his 1940s gladiators.<br />

P R O F I L E<br />

27<br />

24 1/2 × 28 1/8”

28<br />

65 × 69”<br />

In a 1966 conversation with the art critic Harold Rosenberg,<br />

Guston discussed the dilemmas posed by representation: “To<br />

preconceive an image . . . and then go ahead and paint it is an<br />

impossibility for me.” He continued: “<strong>The</strong> trouble with recognizable<br />

art is that it excludes too much. I want my work to include<br />

more. And ‘more’ also comprises one’s doubts about the<br />

object, plus the problem, the dilemma, of recognizing it.”<br />

Guston found his way forward in 1967 and 1968 through<br />

drawings and small paintings that reconciled his distrust<br />

of preconceived imagery with his desire “to include more.”<br />

In 1969 he produced one of the most decisively shocking<br />

statements of his career, <strong>The</strong> Studio, presenting the painter as<br />

a hooded Klansman framed by a dramatic red curtain as he<br />

completes a self-portrait.<br />

Both the meaning and intent of <strong>The</strong> Studio, as well as<br />

Guston’s other paintings showing Klansmen as mobsters<br />

trolling the city or as shadowy figures populating schoolroom<br />

blackboards, have been hotly debated in recent years. Guston<br />

himself declared that the work came about in response<br />

to the Vietnam War and the fraught political climate of the<br />

late 1960s. However, when these works were first shown at<br />

Marlborough Gallery in 1970, remarkably little discussion was<br />

devoted to the implications of this charged imagery—instead,<br />

most critics responded to the manner of Guston’s painting,<br />

seeing in his work a cartoonish betrayal of the ideals associated<br />

with Abstract Expressionism. What contemporary viewers<br />

failed to see was that <strong>The</strong> Studio was both a parable about<br />

the impossibility of painting and a rare self-portrait, probing the<br />

moral stance of the artist in a time of crisis.

P R O F I L E<br />

29<br />

69 × 78 1/2”<br />

Guston had created relatively few self-portraits up to this<br />

stage in his career. He soon cast aside his hooded<br />

personages, instead centering himself, his wife, and his<br />

immediate surroundings in paintings that confronted mortality<br />

and memory. “I found when I was doing these pictures that<br />

I had made a circle,” he stated in 1974. “All my older interests<br />

in painting, the children fighting with garbage cans . . . came<br />

flooding back on me.” Legend (1977, above) encapsulates this<br />

flood of memories as Guston conjures up an uneasy dreamscape.<br />

Weapons seen in his first paintings and in Gladiators<br />

reappear. A flying brick and Officer Pupp’s gloved fist refers<br />

to the Krazy Kat comics of Guston’s youth and to America’s<br />

troubled history of police brutality. A can spewing beer and<br />

the cigarettes and liquor bottle that litter the floor attest<br />

to the bad habits that had undone Guston’s health. A horse<br />

cantering off in the background and an open book allude<br />

to Isaac Babel’s 1926 Red Calvary, a wartime memoir and<br />

testament to anti-Semitism that had moved Guston<br />

profoundly. This cascade of associations has no fixed meaning,<br />

rather it should be understood as the deeply humanistic<br />

moral stance that threaded through Guston’s life and<br />

animated his paintings across many stylistic changes.<br />

In 1966 Guston commented, “I should like to paint like a<br />

man who has never seen a painting, but this man, myself,<br />

lives in a world museum,” a statement that he repeated toward<br />

the end of his life. For Guston the “world museum” ultimately<br />

encompassed more than the world of art. Living vividly in the<br />

present, responding to the most urgent concerns of his generation,<br />

Guston gazed unblinkingly at difficult truths, wrestling<br />

with tragedy and doubt with self-knowledge and compassion.

Sea<br />

Change<br />

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th century, economic<br />

prosperity in the United States allowed for more free time<br />

for the working classes. Leisure was seen as a benefit to the<br />

education, health, and productivity of society, and the beach<br />

was a place where the visual clues of class distinction were<br />

minimized. It was also a place that attracted artists in search of<br />

subjects and new ways to depict them.<br />

Edward Henry Potthast (1857–1927) was one of those artists.<br />

Although originally from Ohio, he had studied art in Europe,<br />

where he absorbed the style of the Impressionists. Between<br />

1889 and 1891, Potthast exhibited works at the Paris Salon, but<br />

ultimately returned to Cincinnati. Five years later, he moved<br />

to New York City, where he found work as an illustrator for<br />

Harper’s and other magazines. Finding success later in life,<br />

Potthast spent his last decades dedicated solely to painting,<br />

and became known for his sun-dappled depictions of outdoor<br />

activities. It was during this time that he discovered one of his<br />

most popular subjects: the beach. In many ways, he combined<br />

the loose brushwork of the American Impressionists with the<br />

bold colors and interest in the crowd, regardless of class, of<br />

the Ashcan School painters. Like those artists, Potthast<br />

focused less on the specifics of his subjects and instead<br />

celebrated the relaxed, happy mood of Americans at leisure.<br />

His Swimming in the Surf (c. 1910) presents a moment from a<br />

perfect day at the beach.<br />

I N T H E M I X<br />

31<br />

20 1/4 × 24”

I N T H E M I X<br />

32<br />

Sheet:<br />

11 × 15 1/4”<br />

Like Potthast, the American artist Maurice Prendergast<br />

(1858–1924) was also drawn to scenes of leisure at the shoreline.<br />

Although born in Newfoundland, he moved with his family<br />

to Boston and later studied in Paris from 1891 to 1895. While<br />

there, he assimilated many Post-Impressionist techniques and<br />

developed his own decorative style using patches of color.<br />

After returning to Boston, he produced a series of enchanting<br />

watercolors along the seashore. Prendergast returned often to<br />

drawing the picturesque town of Marblehead and its surroundings,<br />

observing people on holiday. This watercolor, Marblehead<br />

Rocks, Massachusetts (c. 1905–8), depicts a procession of<br />

figures strolling along the rocky shore while boats sail in the<br />

distance. It was displayed in the first exhibition of <strong>The</strong> Eight—a<br />

group that championed a progressive approach to art—in<br />

1908 and in the prestigious Armory Show in New York in 1913.<br />

Though these two works by Potthast and Prendergast<br />

portray similar scenes, they differ in their stylistic approach.<br />

Whereas Potthast’s loosely brushed figures are a bit more<br />

defined, those by Prendergast appear as a mosaic of bright<br />

pools of color. Together, they demonstrate how American<br />

artists applied what they had learned from their European<br />

counterparts to create their own individualized styles. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

two works are recent gifts to the Museum from the collection<br />

of Nancy Hart Glanville Jewell, a preeminent collector of<br />

American art and a longtime supporter of the Museum. <strong>The</strong><br />

addition of the Glanville Collection uniquely expands the<br />

Museum’s permanent collection of American art.

34<br />

Perfect Form<br />

Buddhist sculptors imagined Buddha’s<br />

perfected body as an amalgamation<br />

of the loveliest and most powerful forms<br />

from nature.

Works from the Xuzhou Collection, never before presented in a public museum, are currently on long-term loan<br />

to the Museum and displayed in the Arts of Asia Galleries in the Caroline Wiess Law Building.<br />

Embodying<br />

Buddhist Ideas<br />

BY HAO SHENG<br />

CONSULTING CURATOR OF ASIAN ART<br />

“ It was Buddhism, rather than the western canon,<br />

which gave me the idea of the abstract body. It<br />

gave me the idea that you can make sculpture<br />

about being rather than doing; that you can make<br />

sculpture that becomes a reflexive instrument<br />

rather than existing as a freeze-form in a narrative.”<br />

—Antony Gormley (British sculptor, born 1950)<br />

I N T H E M I X<br />

35<br />

All Ears<br />

<strong>The</strong> only traces of the Buddha’s<br />

early life of princely luxury are<br />

the long earlobes that were once<br />

weighted down by fine jewelry.<br />

Buddhism holds its own teaching as a means, not an end. In an<br />

often-evoked metaphor, a raft ferries seekers over the river of<br />

ignorance. <strong>The</strong> idea that Buddhist art serves as this vehicle for<br />

enlightenment has been instrumental in the creation of sculptures<br />

such as these in the Xuzhou Collection. For an informed<br />

reader of Buddhist images, the seemingly simple, formulaic<br />

Buddha figures manifest layers of ideas. <strong>The</strong>y signal divine<br />

Buddhahood, recount his earthly biography, demonstrate the<br />

practice of the Middle Path, and embody supreme wisdom.<br />

A Buddha figure bears marks of a “Great Being.” <strong>The</strong> ushnisha,<br />

a prominent bump above his head, is a symbol of expanded<br />

wisdom attained at enlightenment. <strong>The</strong> dot on his forehead<br />

between the eyes, called urna, reveals penetrating visions<br />

beyond our mundane world. <strong>The</strong> figures are often burnished<br />

in gold to capture radiant skin that is said to shine light from<br />

each pore. Encouraged by sacred texts, sculptors imagined the<br />

Buddha’s physical perfection by bringing together the loveliest<br />

and most powerful forms in nature. His broad shoulders and<br />

tapered waist are likened to a lion’s torso, his supple arms to<br />

elephant trunks, his half-closed eyelids to the curvy petals of<br />

a lotus flower, and the folds of his robe to calm ripples over a<br />

deep pool (see opposite page).<br />

Height: 15 3/4”<br />

Height: 18 1/8”

I N T H E M I X<br />

36<br />

Height: 34 7/8”<br />

Down to Earth<br />

In a battle against fear and desire, the triumphant<br />

Buddha touched the ground and invited Earth to<br />

witness his enlightenment.

If marks of perfection confirm Buddhahood, earthly traits on<br />

the same figure recount his life’s journey for enlightenment. He<br />

was born Siddhartha Gautama in 6th century BC, regent to a<br />

north Indian kingdom at the foothills of the Himalayans. <strong>The</strong><br />

prince enjoyed a life of luxury at the palace, was married, and<br />

wore fine garments and gold jewelry. A Buddha figure always<br />

acknowledges this early life with extended ear lobes, which<br />

were once weighted to the shoulders under heavy earrings (see<br />

page 35).<br />

Such extreme care was taken to shield him from life’s sufferings<br />

that the prince did not encounter sickness, old age,<br />

and death until he was 29 years old. Those “Four Encounters,”<br />

the fourth being a wandering ascetic, launched his quest for<br />

enlightenment, in search of an end to the human predicament<br />

of suffering. Having left the palace in the cover of night,<br />

he removed his jewels and cut off his hair in a symbolic act of<br />

renouncing earthly possessions and familial ties. <strong>The</strong> remaining<br />

tufts on his shorn head curled neatly in the characteristic<br />

“snail shells” pattern (see page 34). In place of courtly attire,<br />

Siddhartha wore two rectangular cloths wrapped around his<br />

body, typically with one shoulder bare. Buddhist nuns and<br />

monks to this day, as they set intentions to imitate the Buddha,<br />

undergo ritual head shaving, don versions of Buddha’s simple<br />

garment, and renounce personal wealth.<br />

Siddhartha lived the life of a wandering ascetic for six years.<br />

Having exhausted the practice of extreme austerity, he arrived<br />

at the Middle Path, rejecting both sensual indulgences and<br />

debilitating self-denial. He revived his emaciated body with a<br />

bowl of rice pudding, and then sat down to meditate under<br />

a sacred tree in Bodh Gaya. <strong>The</strong>re, he reached a profound<br />

insight: the sufferings of life are caused by egocentric desires,<br />

and the path to salvation consists of shedding those delusions.<br />

By awakening to the true nature of reality, he attained liberation<br />

from the endless cycle of rebirth. He became the “Awakened<br />

One,” the Buddha.<br />

Some of the most dynamic Buddhist sculptures ever created<br />

depict this moment (as seen at left). Under the boughs of the<br />

Bodhi tree, the Buddha sits cross-legged in deep concentration.<br />

He is surrounded by trouble. <strong>The</strong> demon Mara, standing<br />

with a long bow, first threatens the Buddha with fear, his<br />

grotesque soldiers hurling weapons; then Mara tempts him<br />

with desire, as personified by his alluring daughters. Remaining<br />

immovable, the Buddha extends his right hand to touch the<br />

ground, asking Earth to witness his awakening.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 6th-century Indian sculptor dramatized the moment<br />

with visual contrasts. <strong>The</strong> Buddha is composed of pure<br />

shapes. <strong>The</strong> Diamond Seat (a rectangle) supports the seated<br />

Buddha (a triangle), topped with a halo (a perfect circle). In<br />

contrast, Mara and his cohorts are a mangled mass, all curves<br />

and twisted lumps. <strong>The</strong> smooth and unadorned Buddha, as<br />

if swelling from a breath within, appears luminous against<br />

the pitted and shadowed frame of figures.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Buddha is the center of the narrative, yet he exists<br />

beyond the fray, being at once of the moment and timeless.<br />

In fact, when extracted from the scene of the battle,<br />

the Earth-Touching Buddha (below) is one of the most<br />

repeated icons in Buddhism. His immobile pose and blissful<br />

introspection model a state of being: by mastering the mind,<br />

one may defeat the inner demons of fear and desire. <strong>The</strong><br />

Buddha figure thus embodies his teaching.<br />

<strong>The</strong> sculptures from the Xuzhou Collection (pronounced<br />

“shoe-joe”) present extraordinary range and unparalleled<br />

quality. <strong>The</strong> collector, himself a student of Buddhism, named<br />

the collection in Chinese, meaning “Empty Boat”—a reminder<br />

that the sculptures themselves manifest Buddhist teaching.<br />

Looking beyond the apparent material splendor, viewers are<br />

alerted to the sculptures’ potential to teach and to transform.<br />

37<br />

Height: 20 1/2”<br />

Icon of Enlightenment<br />

Abstracted from the scene of the battle, the Earth-Touching Buddha<br />

remains one of the most iconic images in Buddhism, offering reassurance<br />

in the human struggle against fear and desire.

S E R I E S<br />

A Fiery<br />

<strong>Figure</strong><br />

BY LISA VOLPE<br />

ASSOCIATE CURATOR, PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

When Stokely Carmichael took the stage at the March<br />

Against Fear in Greenwood, Mississippi, on June 16, 1966, the<br />

crowd greeted him with a massive roar. Only weeks before,<br />

Carmichael was elected chairman of the Student Nonviolent<br />

Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to help transition the organization<br />

into a new phase of activism: to create and leverage<br />

the political power of a Black voter base and, in doing so, foster<br />

a greater sense of self-determination and pride. With the<br />

energy of his audience reverberating below, Carmichael<br />

launched the first-ever call for Black Power: “<strong>The</strong> only way<br />

we gonna stop them white men from whuppin’ us is to take<br />

over. We’ve been saying freedom for six years and we ain’t got<br />

nothin’. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!”<br />

As the cry of Black Power echoed through the Mississippi<br />

night, and soon around the world, the phrase—and its<br />

messenger—became a lightning rod of controversy. News<br />

organizations began dissecting and defining the term for<br />

their readership, doing so with various levels of prejudice<br />

38

<strong>The</strong> works shown here are among those featured in Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power,<br />

on view October 16, <strong>2022</strong>, through January 16, 2023, in the Millennium Gallery of the Audrey Jones Beck Building.<br />

and fear. With no ready images of this foreign ideology, media<br />

outlets quickly latched onto photos of Carmichael to represent<br />

Black Power, casting him as a figure of racial violence and<br />

distorting his character and SNCC’s message. Yet, looking<br />

back on this period, Carmichael’s autobiography lists one<br />

published work that was a fair and “sensitive portrait”—<br />

the photographer Gordon Parks’s “Whip of Black Power,” a text<br />

and photo-essay published in Life magazine on May 19, 1967.<br />

Gordon Parks (1912–2006) was one of the 20th century’s<br />

preeminent photographers. He created groundbreaking work<br />

for the Farm Security Administration and magazines such as<br />

Vogue and Life, where he was the first Black staff photographer.<br />

Beyond his work in photography, Parks was a respected film<br />

director, composer, memoirist, novelist, and poet who left<br />

behind an exceptional body of work. In this photo-essay, Parks<br />

details his firsthand experience traveling with Carmichael off<br />

and on from fall 1966 to spring 1967, capturing the activist in<br />

meetings, at lectures, and giving speeches, as well as at more<br />

personal life events, such as his sister’s wedding. <strong>The</strong> artist’s<br />

smart and eye-catching images relay his perspective by drawing<br />

on visual tropes and harnessing connotation, presenting<br />

Carmichael as a changeable and complex figure, his character<br />

drawn as one of nuance and multidimensionality. Taken as a<br />

whole, “Whip of Black Power” represents Parks’s visual translation<br />

of Black Power and its root of self-love.<br />

<strong>The</strong> tide of mass-media imagery was irrevocably turning<br />

by the time Carmichael was elected chairman of the SNCC in<br />

May 1966. Images of passive protests were replaced by Black<br />

participants engaged in an active resistance against oppression.<br />

This change shattered the familiar dynamic. “With the<br />

change of lead visuals came a change of national sentiment.<br />

And with the pronouncement of black power, general sympathy<br />

gave way to a barrage of baffled questions belying white<br />

fear,” author Leigh Raiford summarized. Indeed, the reports<br />

and images that emerged following Carmichael’s speech at<br />

the March Against Fear painted a distinctly ominous message.<br />

In one such photo taken by Bob Fitch, Carmichael appears<br />

as a haunting figure, unnaturally lit against the dark night and<br />

gesturing aggressively at the crowd (see opposite page).<br />

<strong>The</strong> image caption is equally telling, emphasizing anger and<br />

danger: “At a night rally in Broad Street Park, a furious Stokely<br />

Carmichael delivers his famous ‘Black Power’ speech.”<br />

As a denigrated sign of Black radicalism, Carmichael’s<br />

portrait became a one-dimensional, myopic symbol of racialized<br />

fear. Parks’s writing and photographs, however, stand in<br />

direct opposition to that prejudiced point of view. Drawing on<br />

photographic compositions or broad visual motifs familiar<br />

to Life’s readers, Parks forced a recognition of Carmichael’s<br />

full humanity within the pages of the magazine. In doing so, he<br />

created a new, positive image of Carmichael’s character and<br />

Black Power.<br />

Parks’s first image commands the page (see above). It<br />

shows Carmichael speaking into a microphone, his right hand<br />

slashing the air, his left curled into a fist. His conservative suit<br />

is fitted, though he has loosened his tie and unbuttoned the<br />

top button of his white dress shirt. He appears both serious<br />

and charismatic, articulate and agile. <strong>The</strong> crowd Carmichael<br />

addresses in Watts, California, is barely visible; instead, the<br />

cropped image focuses the eye on this mesmerizing and<br />

monumental man. Parks’s text emphasizes the energy of the<br />

moment, describing the amped-up crowd, bodyguards, and<br />

Carmichael, the magnetic force at the center of it all. “This<br />

crowd was made for Stokely Carmichael,” Parks wrote. <strong>The</strong><br />

39<br />

20 × 24”

40<br />

20 × 16”<br />

photograph too celebrates Carmichael’s Black leadership<br />

by drawing visual comparisons to Malcolm X. In 1963 Parks<br />

had photographed the venerated Black leader, dressed in a<br />

conservative dark suit and white shirt, from a low vantage point<br />

as his hand slashed through the air. Here, three years later,<br />

Parks photographed Carmichael in the same way, making an<br />

unmistakable connection between the two figures through the<br />

visual repetition of gesture, camera angle, and details.<br />

In the final photograph of Parks’s profile (at left), a portrait of<br />

Malcolm X appears on the wall above Carmichael’s desk,<br />

among other photos and flyers. Contact sheets reveal that<br />

Parks framed and reframed this scene seven times. Despite<br />

moving closer to Carmichael in subsequent frames, Parks<br />

carefully included the portrait in each one. He clearly<br />

aimed to make the connection between Carmichael and<br />

Malcolm X, casting the young SNCC chair as the recipient<br />

of the elder leader’s legacy. <strong>The</strong> complex image also guides<br />

readers to a more holistic and well-defined sense of<br />

Carmichael’s motivations and emphasizes his fidelity to the<br />

cause: the view of the slumped leader with the symbols of his<br />

Black Power above him recalls scenes of religious pilgrims at<br />

an altar, deep in thought and prayer.<br />

In another image published in the Life profile, Carmichael<br />

poses on a rock-covered road in Lowndes County, Georgia.<br />

Parks’s contact sheets reveal that this was an image he was<br />

intent on creating, capturing Carmichael in various positions<br />

along the road at all times of the day (see opposite page).<br />

However, the largest number of frames feature Carmichael<br />

walking at daybreak. <strong>The</strong>se unpublished images bear a striking<br />

resemblance to the opening photograph of the famous Life<br />

essay “Country Doctor,” from September 20, 1948, by the<br />

photojournalist W. Eugene Smith. Smith’s essay depicts<br />

the modest and tireless Dr. Ernest Ceriani laboring for his<br />

patients in rural Colorado. In that first image, the doctor<br />

traverses the countryside, determined to help his patients.<br />

Parks later claimed “Country Doctor” as one of his favorite<br />

Life essays. His contact sheets of Carmichael’s stroll reveal<br />

that the artist was intentionally referencing Smith’s classic<br />

image, echoing its temperamental skies, rural setting, and lone<br />

figure. By doing so, Parks framed the activist as a selfless local<br />

hero, working for the benefit of others.

S E R I E S<br />

While Parks coded Carmichael’s character through visual<br />

tropes, his first draft of text for the profile also utilized written<br />

analogy. He began:<br />

Stokely Carmichael stood at center stage. Beneath<br />

an angry sky, with the majestic United Nations building<br />

towering behind him; with hundreds of thousands of<br />

peace marchers standing ankle-to-ankle in the wide<br />

plaza cheering him on, he decided to go for broke.<br />

“Vietnam: Hell no! We won’t go!” . . . <strong>The</strong>n a more familiar<br />

cry, hostile, unrelenting and razor-sharp, knifed through<br />

the chant. “Black Power! Black Power! We want Black<br />

Power!” A master stroke. He had two of his slogans<br />

going at once. He was on fire, spitting his heat into<br />

the crowd.<br />

Parks would consistently refer to Carmichael utilizing various<br />

fiery metaphors in his later texts, recalling him “breathing<br />

fire” in his speeches, as part of a generation of “fiery young<br />

insurgents,” and, despite his later resignation as SNCC’s chairman,<br />

as a catalyst for change, predicting, “across the nation<br />

the fires would burn on.”<br />

Gordon Parks understood that visibility mattered. For “Whip<br />

of Black Power,” Parks depicts Carmichael in a holistic and<br />

humanizing manner. A fiery, passionate, and dutiful figure filled<br />

with love for his community, Carmichael is the picture of new<br />

Black leadership and a corpus for Black reflection. <strong>The</strong> creation<br />

of these images of fellowship and self-determination—Parks’s<br />

weapons waged in the battle against erasure and caricature—<br />

was the embodiment of Black Power and an act of fiery love.<br />

This text has been excerpted and adapted from the exhibition<br />

catalogue Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black<br />

Power, published by Steidl in association with the Gordon Parks<br />

Foundation and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.<br />

41<br />

20 × 24”

Self-Reflection<br />

U P C L O S E<br />

42<br />

107 × 178 × 394”<br />

Referred to as an “architect of uncertainty,” the Argentinean artist Leandro Erlich (born<br />

1973) constructs visual paradoxes and optical illusions that force viewers to question<br />

their perceptions and understanding of reality, and to see new possibilities in their<br />

surroundings.<br />

“By design, there is no complete work without the audience,” Erlich says. “<strong>The</strong> audience<br />

temporarily becomes an element of the work itself. <strong>The</strong>ir individual participation<br />

and experience is a level of involvement that makes them essential to the process. And<br />

of course, the ultimate meaning they create and assign is also imperative.”<br />

In Le cabinet du psy (2005), Erlich immerses viewers in an environment composed<br />

of two rooms separated by glass. One of the rooms, which is inaccessible to visitors, is<br />

a painstakingly detailed re-creation of a psychoanalyst’s office, which includes, among<br />

other details, a couch or chaise upon which the potential patient can recline, tapestries,<br />

antique psychology and psychiatry books, assorted knickknacks and sculptural decorations,<br />

and a university diploma.<br />

Viewers are invited to enter the second room, which is essentially a black box with<br />

rudimentary “seats” made up of smaller black boxes arranged to mimic the configuration<br />

of furniture in the adjacent room. A piece of glass separates the two spaces.<br />

Through the reflective qualities of the glass, visitors see their own images projected into<br />

the psychoanalyst’s office, yet they cannot physically enter this area. This produces a<br />

phantasmic, bifurcated reality in which participants experience the sensation of being<br />

in two places at the same time, or at least of feeling their bodies in one space while<br />

seeing them projected in another.<br />

<strong>The</strong> viewer is invited to recline, sit, or stand in the position of the “doctor,” the “patient,”<br />

or even the uninvited visitor, a voyeur who would not normally be included in the<br />

intimate sessions that take place in such spaces. <strong>The</strong> context of the psychoanalyst’s<br />

office seems particularly appropriate for a work that hinges on viewers psychologically<br />

getting outside of their physical selves, even for a moment. Given the focus of psychoanalysis<br />

on exploring the relationship between the conscious and the unconscious, the<br />

disembodied experience encouraged by Le cabinet du psy is an ideal condition for<br />

exploring elements of the unconscious.

Leandro Erlich: Seeing Is Not Believing will be on view through September 5, <strong>2022</strong>, in Cullinan Hall and the<br />

North Foyer of the Caroline Wiess Law Building. In addition to Le cabinet du psy (2005), the exhibition will also include<br />

Erlich’s Bâtiment (2004), in which a mirror reflects viewers onto the facade of a four-story building.<br />

43<br />

A. <strong>The</strong> psychoanalyst’s couch has long been<br />

a signifier of the psychiatrist’s office and<br />

has its roots in Sigmund Freud’s practice,<br />

in which he would ask patients to lie<br />

down in order to create a feeling of ease<br />

or relaxation, encouraging them to be<br />

less guarded and more open.<br />

B. <strong>The</strong> worn books on the shelves are<br />

related to the topics of psychology<br />

and psychoanalysis, and their authors<br />

include giants in the field like Sigmund<br />

Freud and Jacques Lacan.<br />

C. A university diploma on the wall<br />

certifies that the viewer (or patient)<br />

has entered the office of a welleducated<br />

and well-credentialed<br />

psychoanalyst.

Q&A<br />

with<br />

F I V E M I N U T E S W I T H<br />

Leandro<br />

Erlich<br />

44<br />

<strong>The</strong> exhibition Leandro Erlich: Seeing Is<br />

Not Believing ( June 29–September 5, <strong>2022</strong>)<br />

is a homecoming of sorts for the Argentinean<br />

artist Leandro Erlich. During his early<br />

career, he was a Core Fellow (1997–99) at<br />

the Museum’s Glassell School of Art, and he<br />

subsequently went on to earn international<br />

acclaim for riveting and thought-provoking<br />

installations that challenge viewers to<br />

question what they think they see and know<br />

about themselves and the world around<br />

them. In this interview, Erlich reflects on<br />

the issues and ideas that drive him to create<br />

extraordinary works where the viewer<br />

participates as a “co-creator.”

Le cabinet du psy (2005) immerses the viewer in a<br />

psychoanalyst’s office. Can you talk about your interest<br />

in psychoanalysis, how it developed, and how it informs<br />

your work?<br />

As someone who grew up in Buenos Aires, which has one of<br />

the highest concentrations of psychoanalysts in the world,<br />

it’s unavoidable. Our daily discourse is full of the language of<br />

psychoanalysis, as are people’s daily lives. French structuralists<br />

have also been very important for Argentine intellectuals, so we<br />

are always on the divan in one way or another. My work is often<br />

associated with the Freudian concept of the uncanny, which<br />

is certainly present in this piece, where we are “neither here<br />

nor there,” where the ordinary has become suddenly and<br />

mysteriously strange.<br />

Does a variation of voyeurism—or a kind of autovoyeurism,<br />

if you will—play a role in Le cabinet du psy?<br />

At first glance, viewers seem to be offered an opportunity<br />

to peek in on a private space, one where theoretically<br />

the unconscious will also be on “display” through the<br />

process of psychoanalysis, which could add another level<br />