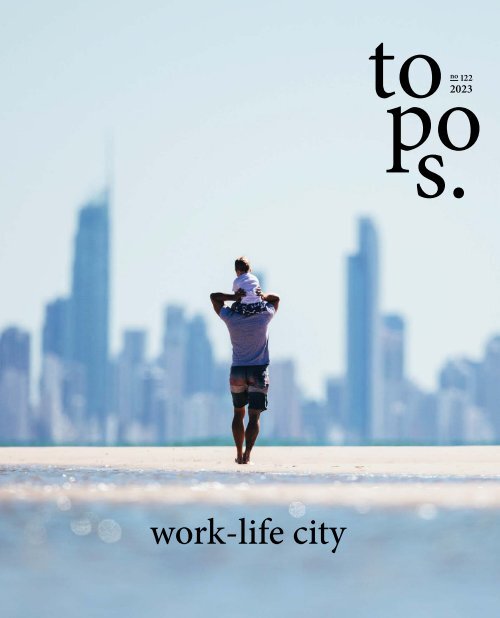

topos 122

work - life - city

work - life - city

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

no <strong>122</strong><br />

2023<br />

to po s.<br />

work-life city

COVER<br />

PHOTO: City of Gold Coast<br />

Less work, but more time for family, friends<br />

and leisure. These days, many people look for a<br />

good balance between work and life. Or in<br />

other words: a better quality of life all around.<br />

In this <strong>topos</strong> we discuss how metropolitan<br />

areas can support the work-life balance of<br />

their residents – and why this is also a key<br />

responsibility of the metropolis.<br />

Mindfulness, meditation, social detox – finding<br />

a balance in everyday life, between work, family,<br />

friends, sports and smartphone, seems to have<br />

become the most important asset for many – especially<br />

younger – people. Several studies confirm<br />

that a supposedly "good" work-life balance<br />

is now actually particularly important for many<br />

people – for example, more important than their<br />

salary. The new target of self-optimization, malicious<br />

tongues might think.<br />

Less work, but more time for family, friends and<br />

leisure. Or in other words: a better quality of life<br />

all around. Most people probably wouldn't say<br />

'no' to that. If that's possible. Because ultimately,<br />

it is a luxury, the balance between life and work.<br />

Who can afford to work a four-day week, but<br />

only get paid for four days? Very few. Work-life<br />

balance is reserved for an elite group. To which I<br />

must count myself. And you, presumably, too.<br />

Even if only about ten to 20 percent of the<br />

world's population can afford to work actively<br />

on their work-life balance, it is already visible everywhere<br />

in our cities. You tell me: Have there<br />

ever been more yoga studios? Life coaches? Feel<br />

good managers? I would say 'no.'<br />

Nonetheless, cities or urban structures can also<br />

help support the daily balance of all city dwellers,<br />

support their quality of life. Regardless of their<br />

income or wealth. This is precisely what must be<br />

the goal of public welfare-oriented urban planning.<br />

And it is also necessary: According to a<br />

Swedish study of 4.4 million people, residents of<br />

densely populated areas – in contrast to people in<br />

rural areas – have a 68 to 77 percent higher risk of<br />

developing a psychosomatic illness and a 12 to 20<br />

percent higher risk of depression. The research<br />

field of neurourban studies is still quite young<br />

and small, but we already know: cities make people<br />

sick. Physically and mentally.<br />

So how can metropolitan areas support the<br />

work-life balance of their residents (and by that I<br />

mean everyone)? We discuss no less than that in<br />

this <strong>topos</strong> issue. Based on our research, we have<br />

defined seven topics that are crucial for a better<br />

quality of life in a city: one's income (dollar bill<br />

y'all), the available recreational facilities (yes,<br />

there are some things money can't buy), whether<br />

a city is family-friendly (or rather what that actually<br />

means), whether it offers social security (and<br />

why everyone suffers from FOMO), how to get<br />

around (bye bye traffic jams), how to live (hi<br />

one-bedroom apartment) and finally what the<br />

opportunities for work are now after the pandemic<br />

(did you know that Australia is known to<br />

be the best place for digital nomads?). Our objective<br />

is to analyze what is important in our cities,<br />

but above all what is possible.<br />

Of course, when it comes to work-life balance,<br />

each of us needs something different. Even if cities<br />

have long since started the race for the highest<br />

quality of life or work-life balance. With such a<br />

personal topic, there can be no general easy solutions.<br />

But to get an understanding of how diverse<br />

these life realities can be, we introduce you to<br />

three extraordinary people and their perspectives<br />

on living and working in a city. Enjoy reading.<br />

TOPOS E-PAPER: AVAIL-<br />

ABLE FOR YOUR DESKTOP<br />

For more information visit:<br />

www.<strong>topos</strong>magazine.com/epaper<br />

THERESA RAMISCH<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

t.ramisch@georg-media.de<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 005

CONTENTS<br />

OPINION<br />

Page 9<br />

THE BIG PICTURE<br />

Page 10<br />

CURATED PRODUCTS<br />

Page 102<br />

REFERENCE<br />

Page 106<br />

METROPOLIS EXPLAINED<br />

Page 12<br />

URBAN PIONEERS<br />

Page 14<br />

THE SOLUTION BUILDERS<br />

Page 76<br />

Photos: Mary Grace Long Photography, Rob Potter via Unsplash<br />

AND THE WINNER IS… OSLO<br />

The top work-life cities in the world<br />

Page 22<br />

INCOME AND HEALTH<br />

The impact of income on life expectancy<br />

Page 24<br />

LOOKING FOR YOUR HAPPY PLACE?<br />

The world's happiest countries<br />

Page 28<br />

URBAN GAMES<br />

How Paris prepares for Olympia<br />

Page 36<br />

THE OPEN-HEARTED<br />

A portrait of child counsellor Shanti Hetz<br />

Page 38<br />

BABY STEPS<br />

Improving major aspects of children’s lives<br />

Page 44<br />

A CHILD-FRIENDLY CITY<br />

What would it look like?<br />

Page 46<br />

THE PRIVILEGE OF MISSING OUT<br />

FOMO has become a serious urban issue<br />

Page 52<br />

THE PAID ACTIVIST<br />

A portrait of climate expert Andrea Zafra<br />

Page 60<br />

RACE AND PLACE<br />

The California Healthy Places Index<br />

Page 66<br />

COMMUTING AND MENTAL HEALTH<br />

It's the way we travel we should consider<br />

Page 68<br />

LONG LIVE THE BIKE<br />

Cycling is not only hip and<br />

good for the climate<br />

Page 74<br />

SAFER CITIES<br />

What makes a city safe?<br />

Page 82<br />

DARING UTOPIA<br />

What we need to do now – a commentary.<br />

Page 84<br />

SKY HIGH STANDARDS<br />

San Francisco’s Harvey Milk Terminal 1<br />

Page 88<br />

WORKING FROM HOME<br />

How it changed us forever<br />

Page 90<br />

NO HOME BUT THE BEST HOME<br />

The best countries for a digital nomad life<br />

Page 98<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Page 100<br />

CITY GAME CHANGERS<br />

Page 112<br />

IMPRINT<br />

Page 113<br />

EDGE CITY<br />

Page 114<br />

THE BENEFITS OF SPORTS AND<br />

OUTDOOR SPACES IN THE CITY<br />

Page 30<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 007

THE BIG PICTURE<br />

Swim City<br />

Forget the Hamptons, Bondi Beach, the Florida Keys, etc. Summer is best spent where? In Switzerland.<br />

Strangely enough. Here, an urban trend has manifested itself in recent years: river swimming. While Berlin,<br />

London and Paris were still struggling with the implementation of their river pools, people in Basel, Bern,<br />

Geneva or, as pictured, the city of Zurich, were already jumping into the city river at all times of the day -<br />

without paying any entrance fees, of course. According to the organizers of the exhibition "Swim City" at the<br />

S AM Swiss Architecture Museum, river swimming is possible primarily because of Switzerland's pragmatic<br />

legal approach to risk. The difference: In contrast to many other countries, swimming in moving water is<br />

legally permitted in this country. At the same time, however, no one in Switzerland denies that swimming in<br />

flowing water is risky. Information about the requirements and dangers is provided in many places. The<br />

population is trusted to realistically assess risks and their own swimming abilities. Switzerland is thus living<br />

a culture of democratized risk, creating new public space free of consumption – and pure quality of life.<br />

TEXT: THERESA RAMISCH<br />

010 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

The Big<br />

Picture<br />

Photo: Lucía de Mosteyrín<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 011

METROPOLIS EXPLAINED: STEVEN KRETZMANN<br />

Capetown<br />

The mountain, with its sheer cliffs rising<br />

above the white sand and turquoise water of<br />

Cape Town’s beaches, makes the city unique<br />

in providing a 25,000 hectare national park in<br />

its midst. Within minutes, you can travel from<br />

a cosmopolitan city centre of art galleries,<br />

bars, theatres, renowned restaurants, and<br />

buzzing coffee shops, to step onto a trail leading<br />

into a wilderness housing the most diverse<br />

floral kingdom on the planet outside of the<br />

tropics. Being only about 350 years old, Cape<br />

Town lacks the grand architecture of European<br />

and Asian cities, but it is where the graceful<br />

Cape Dutch architecture was born, and the<br />

city retains many of its Georgian and Victorian<br />

buildings, particularly along Long Street,<br />

its nightlife strip. Contemporary architectural<br />

styles are also evident, particularly at private<br />

homes along the Atlantic seaboard, which is<br />

some of the most expensive real estate on the<br />

continent. It is a cosmopolitan city with a cutting<br />

edge cultural scene as evidenced in the<br />

Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art<br />

designed by the acclaimed Thomas Heatherwick,<br />

the Baxter Theatre with its international<br />

touring shows, outdoor concerts by in the<br />

famed Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens, and<br />

vibrant nightlife. It is also a city of extreme<br />

contrasts and contestation. It has villas worth<br />

more than 11 million Euros while hundreds<br />

of thousands of residents live in corrugated<br />

iron shacks with inadequate access to water<br />

and sanitation: the injustices of the past continually<br />

rub against the progress of the present.<br />

The first thing the Dutch did when they<br />

set up a refreshment station at Table Bay was<br />

build a castle – still standing and in use by the<br />

national defence force today – and violently<br />

dispossess the native Khoi herders of their<br />

traditional grazing lands. This was the genesis<br />

of the colonisation of southern Africa later<br />

perfected by the British. The Khoi, along with<br />

the slaves imported from Africa, Madagascar,<br />

Malaysia, and Indonesia, were pushed to the<br />

margins of society. This marginalisation of<br />

people of colour was further entrenched<br />

under apartheid, which rebuilt the city along<br />

racial lines. The apartheid spatial planning<br />

That Cape Town is one of<br />

the most beautiful cities<br />

in the world is not contested.<br />

With Table Mountain<br />

as a backdrop and<br />

encircled by the mountain’s<br />

flanks, the city<br />

bowl, in the middle of<br />

which are the sprawling<br />

public gardens originally<br />

established by the Dutch<br />

East India Company to<br />

supply fresh produce to<br />

their ships on the way to<br />

the East Indies, looks out<br />

across the harbour,<br />

northwards toward the<br />

rest of Africa.<br />

STEVE KRETZMANN has worked as a journalist for 23<br />

years, having founded the news agency West Cape<br />

News in 2006, mentoring young adults to provide previously<br />

overlooked stories of Cape Town and surrounds<br />

to the South African, and international press.<br />

The growth of free online news led to West Cape News<br />

having to close offices in 2013, with Steve continuing<br />

as a freelancer, covering social justice, the environment,<br />

and, through his site The Critter, the arts. He is<br />

also editor of monthly community newspaper Mother<br />

City News. After growing up in Johannesburg, he first<br />

moved to Cape Town in 1992, later studying at Rhodes<br />

University in Makhanda.<br />

still dogs the city even as global corporations<br />

oversee a new colonisation: Amazon is controversially<br />

building its new African headquarters<br />

on the site of original colonial dispossession<br />

along the Liesbeek River bank, a<br />

development supported by city authorities<br />

but mired in litigation brought by the descendent<br />

of the Khoi who lived at the foot of the<br />

mountain before the Dutch East India Company<br />

– the original global corporation –<br />

arrived. Economic segregation has replaced<br />

racial segregation. The working class, who are<br />

predominantly people of colour, still live far<br />

from the opportunities of the city centre, in<br />

crowded townships on the sandy wastelands<br />

that form the isthmus between Table Mountain<br />

and the rest of the continent. The city<br />

bowl and wooded mountain slopes remain<br />

reserved for the rich, who remain predominantly<br />

white and increasingly international.<br />

Thus for the privileged, Cape Town is an idyllic<br />

city with all the convenience of fast internet<br />

and world class infrastructure, with culture<br />

and work opportunities on the doorstep<br />

and untrammelled wilderness in the backyard.<br />

But with an official unemployment rate<br />

at 29,5 percent and an average annual household<br />

income of about 3,000 Euros, this is not<br />

the experience of the majority. It is thus not<br />

surprising that a getkisi survey of 100 cities<br />

with the best work-life balance for 2022<br />

placed Cape Town last. Most residents have<br />

to rise at dawn and spend an hour or more on<br />

dysfunctional and unsafe public transport to<br />

get to work or school, returning only after<br />

dark, with visits to the beach or the mountain<br />

confined to a handful of special days during<br />

the year. Yet, Cape Town is the most functional<br />

and financially healthy city in South Africa,<br />

predicted to double in population to about<br />

10 million within a generation. With a politically<br />

stable administration, policy geared to<br />

providing affordable housing close to work<br />

opportunities and fixing the failing public<br />

transport system, Cape Town is starting to<br />

dismantle its divisive planning history and<br />

hopefully becoming a city that can be<br />

enjoyed by all who live in it.<br />

012 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

Metropolis<br />

explained<br />

Map: openstreetmap.org<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 013

URBAN PIONEERS: MAGDALENA STEINHAUSER<br />

Parkour Generations<br />

Leaping down entire flights of stairs, climbing<br />

walls, vaulting over balustrades – what seems<br />

daunting or just plain dangerous to most of us<br />

is exactly what those practicing parkour love<br />

doing. This strictly non-competitive sport has<br />

the aim of moving efficiently across any terrain<br />

and surrounding using only your own body.<br />

Those practicing the sport, which was originally<br />

termed “Art du Deplacement”, seek to become<br />

physically, mentally, and ethically strong. It is a<br />

sport that does not simply train the body. “Traceurs”<br />

aim to be able to rely on themselves, be<br />

adaptable, protect the environment, be disciplined,<br />

value friendships and community, and<br />

be of service to others.<br />

“Public spaces are there to be used, embraced,<br />

explored – both for kids and adults, and nothing<br />

does that better than parkour.” That is the<br />

motivation for Parkour Generations – one of<br />

the pioneer organizations in the sport. The<br />

internationally active professional parkour<br />

organization with headquarters in London, UK<br />

was founded in 2005. Over fifteen years later<br />

they have received several awards for their work<br />

and have established gyms in multiple cities<br />

across the UK as well as the U.S., South Korea,<br />

and Brazil. They have become the first and largest<br />

parkour teaching and certification framework<br />

in the world.<br />

“Urban living has typically reduced most modern<br />

people's movement throughout their day<br />

and has certainly reduced the variety of movement,<br />

and that's a huge problem and one that is<br />

heavily responsible for the many common<br />

health issues we see in our populations.” To<br />

tackle this issue for people from all walks of life,<br />

they create spaces where children, teens, adults,<br />

people with disabilities, and the elderly can all<br />

find their peers. They are convinced that “the<br />

human body is the perfect adaptive movement<br />

organism, literally evolved for practical movement<br />

over almost any terrain. It wants to move,<br />

and the more it does so the fitter, stronger and<br />

healthier it will be, and the longer it will last.“<br />

There could hardly be a more straightforward<br />

way to engage with your urban environment, to<br />

get to know the very materials utilized in building<br />

a city, and to get to evolve alongside it. Parkour<br />

is about learning to be as resilient as your<br />

environment. It encourages a shift in how you<br />

view your surroundings and to find playful<br />

solutions to any obstacle.<br />

Outsiders might be somewhat skeptical of a<br />

sport that initially seems mainly to be encouraging<br />

people to smash their bodies into concrete<br />

walls. But in parkour, the “traceur’s” safety<br />

is always at the forefront. Instead of trying to<br />

ace the craziest tricks, the aim is self-mastery<br />

and self-knowledge. It demands full focus and<br />

forces you to concentrate entirely on yourself.<br />

This teaches those practicing the sport to know<br />

their limits, to respect them, and to playfully<br />

work on expanding them.<br />

Just like the sport itself, Parkour Generations<br />

want to have a positive impact on urban communities.<br />

Through multiple outreach programs<br />

and initiatives for women and people of different<br />

backgrounds and abilities, they “help people<br />

reclaim their movement and learn to apply<br />

their physicality within their urban environment<br />

– not just taking the train to get to a gym<br />

but using the city as your gym!” They run cleanup<br />

events, offer training for the military and<br />

police, and give presentations to international<br />

governing bodies.<br />

Seeking to create more urban spaces that<br />

encourage a playful engagement with our surroundings,<br />

they frequently collaborate with<br />

landscape architects and urban planners.<br />

We can probably all agree with them that the<br />

urban world needs more spaces designed to<br />

encourage, support, and integrate healthy<br />

movement into our lives. What if we reimagined<br />

the design of public spaces altogether by<br />

shaping them in a way that encourages free<br />

play and movement?<br />

MAGDALENA STEINHAUSER studied English Literature<br />

and Literary Translation in Norwich, UK and<br />

trained as an editor before becoming part of Georg<br />

Media in March 2022.<br />

014 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

Urban<br />

Pioneers<br />

Photo: Parkour Generations / Pawel Gawronski<br />

"Our cities are here to stay, and urban populations will continue to grow; the<br />

future lies in us adapting to these places to make them work for us rather<br />

than against us – and that means reclaiming our spaces for movement."<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 015

Work-life balance is the idea of balancing<br />

the demands and responsibilities of an individual's<br />

job with the time and energy required<br />

for their personal and family life. It encompasses<br />

the time, energy, and effort that a person<br />

dedicates to their job and their personal<br />

life, including relationships, hobbies, and other<br />

interests. In practice, work-life balance<br />

means finding the right balance between time<br />

spent on work-related tasks and time spent on<br />

personal pursuits. Being a personal and subjective<br />

concept, however, different aspects of<br />

work-life balance that work for one person<br />

may not work for another. Factors that can impact<br />

work-life balance include job demands,<br />

hours of work, commuting time, and family<br />

responsibilities. Achieving work-life balance<br />

requires effort and often requires making<br />

changes to one's work habits and schedule.<br />

This can include finding ways to delegate or<br />

outsource work, setting clear boundaries<br />

between work and personal life, and finding<br />

flexible work arrangements. A challenge, especially<br />

in today's fast-paced, always-connected<br />

work environment. Failing to find the right<br />

balance may result in burnout, stress, and<br />

decreased job satisfaction.<br />

Burnout in particular is on the rise internationally.<br />

The "State of the Global Workplace<br />

Report", a survey conducted annually by the<br />

market research institute Gallup, shows that 38<br />

percent of respondents from over 100 countries<br />

experienced stress at work in 2019. In 2020,<br />

that number rose to 43 percent – in part<br />

because of the Covid 19 pandemic. Another<br />

survey conducted by the employment website<br />

Indeed shows that at 52 percent, more than half<br />

of the 1,500 U.S. workers surveyed across a<br />

range of ages, experience levels and trades experienced<br />

burnout in 2021.<br />

A number of factors play a role in ensuring<br />

a healthy work-life balance and thus preventing<br />

burnout. There are work-based factors, such as<br />

the number of vacation days an employee is<br />

legally entitled to in a country. In Finland, for<br />

example, employees are legally entitled to 25<br />

vacation days. In the USA, the average is just<br />

about 10 days. Even more interesting, however,<br />

is the number of days actually taken by<br />

employees. According to the "Work-Life Balance<br />

Index" from access control solution provider<br />

Kisi, employees in the Finnish capital<br />

Helsinki took a full 30 of the 25 vacation days<br />

to which they are legally entitled in 2022. The<br />

higher figure is partly due to the fact that individual<br />

contractual arrangements can also allow<br />

for more vacation days than the legal minimum.<br />

In Las Vegas, employees take an average<br />

of only 8.4 out of 10 vacation days. The reason<br />

for this is, among other things, the fear of being<br />

seen as indolent by taking the full amount of<br />

vacation. It becomes clear that, in addition to<br />

the legislation, the work culture in a country<br />

also plays a role when it comes to exhausting<br />

the legal requirements and thus achieving a<br />

balance between work and life. Other factors<br />

relate to society and institutions. These include<br />

the availability of high-quality medical care for<br />

physical illnesses and low-threshold access to<br />

mental health care services.<br />

While ensuring a healthy work-life balance initially<br />

seems to be a matter for the individual<br />

and is mainly owed to the working circumstances<br />

in a country, the city itself can also<br />

contribute to ensuring that residents can sufficiently<br />

recover from their efforts at work. One<br />

obvious factor in this regard is the recreational<br />

opportunities available in a city. High-quality<br />

parks, for example, ensure that citizens can<br />

pursue leisure activities that are close to<br />

nature.<br />

At the same time, recreational facilities in a<br />

city should be quick and easy to reach, since<br />

practical experience shows that the frequency of<br />

visits decreases drastically with increasing travel<br />

time. We must also not forget the effects of travel<br />

times in general. The length of the daily commute<br />

within the city has an undeniable influence<br />

on the balance between work and private<br />

life. People who have to spend less time on the<br />

road have more options for leisure activities and<br />

at the same time more time to pursue their private<br />

lives. A keypoint to this is a well-functioning,<br />

affordable public transport system with<br />

high frequencies and good punctuality, as it<br />

shortens commute times and thus allows for a<br />

higher degree of leisure time.<br />

But as you will read from page 68, it is not<br />

only important that urban transportation systems<br />

get as many people from A to B as quickly<br />

and cheaply as possible, but also how pleasant<br />

the transit is. Outdated and uncomfortable subways,<br />

where people are crammed in like a cattle<br />

truck, are unlikely to reduce stress levels among<br />

travelers. Ultimately, the duration and quality<br />

020 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

work-life city<br />

of commuting in a city not only has effects on<br />

the health of the individual, but also consequences<br />

for society.<br />

Another keypoint to a good work-life balance,<br />

however, is affordable housing. By offering<br />

affordable housing near citizens' everyday stops,<br />

especially of course the workplace, cities can<br />

reduce the time and money spent commuting,<br />

giving individuals not only more time but also<br />

more resources to focus on their personal lives.<br />

But how affordable housing is, is also an inseparable<br />

consequence of income levels. Of course,<br />

the more money you have, the cheaper housing<br />

will seem to you. The differences here do not<br />

only exist between national borders. Even within<br />

the same country, socio-economic differences<br />

can be drastic. Read more about this specific<br />

topic from page <strong>122</strong>.<br />

One particularly effective method that cities<br />

can use to kill several birds with one stone in<br />

order to promote a good work-life balance<br />

amongst other things is to promote bicycle traffic.<br />

Not only does it relieve road congestion as<br />

more residents bike to work, shopping, or to<br />

visit acquaintances. It also has positive effects<br />

on residents' health, encourages a healthier lifestyle<br />

in general and reduces stress levels. An interesting<br />

article on this topic and on which cities<br />

are exemplary in promoting the health of<br />

their residents through sports activities can be<br />

found from page 30.<br />

Offering good childcare can also help a city<br />

offer a good work-life balance. By offering highquality,<br />

affordable child care options, cities can<br />

help working parents better balance the<br />

demands of work and family while at the same<br />

time reducing gender inequality. It is not only<br />

from the children's point of view that it is beneficial<br />

for a city to be child-friendly and to provide<br />

an environment where children have<br />

"everyday freedoms". Playgrounds, as found in<br />

many cities today, tend to be "play ghettos" that<br />

children often cannot get to without their parents'<br />

help because of the dangers of intervening<br />

traffic. The problem here is that urban planning<br />

is centered around cars, housebuilding and the<br />

economy – not the environment, health and<br />

quality of life. Starting on page 46, you'll find<br />

good examples of cities committed to being<br />

child-friendly.<br />

Whether it is Oslo, Bern, Copenhagen or<br />

Sydney, a city with a good work-life balance is<br />

always the result of a combination of many factors.<br />

Cultural and social issues play a role, as do<br />

legal and building requirements. The cities with<br />

the best work-life balance in the world consistently<br />

get a lot right in these areas. However, the<br />

cities that occupy the top positions in any ranking<br />

that you will find have one characteristic in<br />

common that cannot quite be measured in figures:<br />

they are particularly beautiful and all of<br />

them are popular destinations among tourists.<br />

In this issue of <strong>topos</strong>, you will not only find<br />

interesting concepts and surprising facts about<br />

work-life balance. We will also introduce you<br />

to inspirational people and their approach to a<br />

healthy balance of work and life. In any case,<br />

after reading this issue you will see the worklife<br />

balance in your city with different eyes.<br />

Enjoy reading!<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 021

Income<br />

and<br />

Health<br />

JULIA TREICHEL<br />

024 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

work-life city<br />

Poverty makes people sick. As striking as this statement sounds, it is just as real<br />

for many people around the world. Although access to the best possible healthcare<br />

is enshrined in the human rights of the United Nations, there is still a high<br />

degree of inequality in healthcare internationally. And the differences are not just<br />

along geopolitical lines. Conditions within a country also diverge widely due to<br />

socioeconomic differences. What responsibility does the metropolis have in this?<br />

People at risk of poverty have a significantly lower life expectancy. This<br />

was announced by those responsible for the 24th Public Health Congress<br />

at the Technical University of Berlin (Germany) in 2019. Studies by the<br />

Robert Koch Institute, the federal government agency and research institute<br />

responsible for disease control and prevention in Germany, support<br />

this statement with clear figures. In this context, people are considered<br />

poor if they have less than 60 percent of the median income at their disposal.<br />

This is because poverty is not measured globally but is based on<br />

the standard of living in the respective country. Someone who falls below<br />

the poverty line in one country could still be considered rich in another.<br />

Since the cost of living varies from country to country, regional analysis<br />

has become established. For this purpose, the median income is determined.<br />

It is measured from the middle of the total income of a country.<br />

Poverty affects those who earn less than 60 percent of this.<br />

The effects for those at risk of poverty are devastating. According to<br />

the Robert Koch Institute, the average life expectancy for men at risk of<br />

poverty is reduced by 8.6 years in contrast to those with higher incomes.<br />

For women, the difference is still 4.4 years. It is a startling statistic that is<br />

even more shocking because it shows a trend. According to researchers,<br />

the gap has widened over the last 25 years. The medical conditions that<br />

affect low-income people are diverse. For example, they are two to three<br />

times more likely to develop diabetes or cancer. Likewise, the likelihood of<br />

a heart attack or stroke increases. But it is not only the physically measurable<br />

consequences that are significant.<br />

A sad prime example<br />

It is also precisely the effects that are not directly visible that burden<br />

many people affected by poverty. An international team from the Massachusetts<br />

Institute of Technology published a report on this in 2020. Data<br />

from Japan, Switzerland and Brazil was taken into account. It shows<br />

that people living in poverty are more likely to be affected by mental illness<br />

than the average population. In their research, the scientists found a<br />

one-and-a-half to three times greater incidence of anxiety disorders and<br />

depression among low-income groups. They also reported higher rates<br />

of schizophrenia and suicide in this wage group.<br />

For a long time, Glasgow was sadly a prime example of this observation.<br />

According to 2010 statistics, residents* had a 30 percent higher risk<br />

of dying before the age of 65. Many of them at the hand of suicide or<br />

drugs. The long unexplained phenomenon became known as the<br />

Glasgow Effect. David Walsh of the Glasgow Centre for Population<br />

Health and his team published a report in 2016 with hypotheses to<br />

explain the mortality rate. The main point they highlighted was the high<br />

level of poverty in the city. But they didn't stop there. They further noted<br />

that urban developments since the 1950s had made Glasgow's population<br />

more vulnerable to the effects of deindustrialization and poverty.<br />

And, as a result, more sensitive to adverse health effects. This was because,<br />

to deal with overcrowding, local authorities had decided in the<br />

postwar period to house people in high-rise buildings on the outskirts of<br />

the city center. Others were relocated to new towns in the surrounding<br />

area. These radical measures rapidly changed the composition of the<br />

population. Although people had more space within their new apartments,<br />

the once familiar social fabric was thrown out of kilter. Formerly<br />

familiar neighborhoods broke apart. The changed housing situation created<br />

a spatial, but not a social density with the new neighbors. This anonymity<br />

led to mistrust, insecurity and social stress. Furthermore, the residents<br />

felt less responsible for their surroundings. The housing projects<br />

visibly deteriorated and were largely demolished in 2016.<br />

The impact of a socially cluttered environment<br />

It is only a fragment of Glasgow's multifaceted urban history, but it<br />

shows the influence of the built environment on mental health. Similarly,<br />

in 1973, psychologist Andrew Baum conducted a much-cited study of<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 025

Urban living is often associated with increases in mental health problems and<br />

with challenges to physical health. On the other hand, cities offer great opportunities<br />

to exercise, to socialise, and some even to enjoy nature. How do urban<br />

sport and outdoor offers influence work-life balance? And which cities are exemplary<br />

in boosting the mental and physical health of their residents? Can urban<br />

planning have any effect at all on the health of citizens?<br />

According to the Centre for Urban Design and<br />

Mental Health, living in a city is associated<br />

with increases in mental health problems: 39<br />

percent more mood disorders, 21 percent more<br />

anxiety disorders, a heightened risk of schizophrenia,<br />

and an increase in the rate of cocaine<br />

and heroin addiction are some of the challenges<br />

of urban living.<br />

At the same time, the World Health Organization<br />

has declared a public health emergency<br />

in cities because more than 90 percent of urban<br />

residents live in areas where air pollution<br />

exceeds the agency’s guidelines. Respiratory diseases,<br />

an increase in obesity, and a decrease in<br />

brain capacities are some of the consequences<br />

of air pollution as per the WHO.<br />

Thankfully, there are also some positive<br />

aspects of living in cities regarding our physical<br />

and mental health. The Centre for Urban Design<br />

and Mental Health has found that city life<br />

decreases suicide risk and Alzheimer’s disease<br />

occurrence by almost half. Compared to rural<br />

living, dementia and abuse of drugs tend to be<br />

lower in cities as well, according to their research.<br />

At the same time, cities that have abundant green<br />

spaces, outdoor gym equipment, a varied topography,<br />

and other wellbeing and sports factors, as<br />

well as measures for cleaner air, are among the<br />

most attractive to live in, as the Economist’s global<br />

liveability index shows every year.<br />

How can urban design help improve health?<br />

Cities can significantly affect both the physical<br />

and mental health of its residents either negatively<br />

or positively. Therefore, the challenge lies<br />

in designing cities that support healthy citizens.<br />

This is not an easy task and there are confounding<br />

factors, as the Centre for Urban Design and<br />

Mental Health points out: In addition to urban<br />

environmental factors that impact on mental<br />

health, there are pre-existing risk factors, socioeconomic<br />

factors, and a reporting bias. In addi-<br />

032 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

work-life city<br />

tion, it is not easy to measure the effects that an<br />

urban environment has on health. Sedentary lifestyles,<br />

fast food, and a lack of movement are other<br />

factors that impact our health both in cities<br />

and everywhere else. Self-reported wellbeing and<br />

happiness of urban residents show that there are<br />

certain urban design features that can improve in<br />

particular mental health. Leyden et al. are among<br />

the researchers who have found that the following<br />

aspects of urban design are key:<br />

Access to nature<br />

Access to natural outdoor settings in a neighbourhood<br />

and in daily routines has been shown<br />

to improve general mental wellbeing, to reduce<br />

depression and stress, to improve social and cognitive<br />

functioning, and to improve moods. This<br />

is due to the promotion of exercise, but also due<br />

to the possibility of building social networks in<br />

nature, to the distance it creates away from<br />

everyday demands, and to the biological interest<br />

of humans to be in contact with other species.<br />

The centre for Urban Design and Mental<br />

Health lists some urban design action points to<br />

better meet this requirement for health in cities.<br />

These include the creation of walkable green<br />

space, which according to the Centre’s researchers<br />

has the most impact on mental health. Similarly,<br />

the overall greenness of neighbourhoods<br />

and access to consistent and regular exposure to<br />

urban nature are very important. Urban planners<br />

can integrate features such as street trees<br />

and flowers, views of nature, gardens for lunch,<br />

and walkable spaces into everyday lives. Importantly,<br />

urban outdoor spaces need to be wellmanaged<br />

to have a positive impact on mental<br />

health, as recommended by the WHO. In addition,<br />

other factors outside of urban design are<br />

needed to support mental health, from accessible<br />

therapy to social relationships and healthy<br />

lifestyles. Example: According to the European<br />

Environment Agency, trees cover about 30 percent<br />

of land in 38 European capitals. This number<br />

is much higher in Oslo, which has a share of<br />

72 percent allocated to green space. Almost all<br />

the city’s residents, 95 percent, live within 300<br />

metres of a park or an open green space.<br />

Space for sports<br />

Active spaces are another important element of<br />

cities that promote health, the Centre for Urban<br />

Design and Mental Health has found out. The<br />

experts state that positive, regular exercise<br />

improves the mood, the wellbeing, mental health<br />

outcomes, as well as the physical health of urban<br />

residents. Regular exercise can be as effective as<br />

antidepressants when it comes to treating mild to<br />

moderate depression, according to the WHO.<br />

Sport can also improve self-esteem, wellbeing,<br />

anxiety, stress, ADHD symptoms, dementia<br />

symptoms, and even schizophrenia. In addition,<br />

exercise helps to counteract weight gain and<br />

reduce the risk for diabetes and obesity. Other<br />

benefits of urban spaces for exercise, according to<br />

the Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health,<br />

are the promotion of stress-resilience and the<br />

opportunities for positive social interactions.<br />

While the positive therapeutic effects of exercise<br />

on depression and anxiety disorders are well<br />

documented, evidence of a preventive effect is<br />

difficult, as there are many factors that interact.<br />

The question of cause and effect for that particular<br />

relationship has not been settled.<br />

Planning for exercise opportunities in cities<br />

can include active modes of transport, such as<br />

bike shares, protected bike lanes, safe walkability,<br />

and convenient connections to different<br />

parts of the city. Good public transport will<br />

encourage walking between train or bus stops<br />

and destinations, while well-designed stairs can<br />

be more attractive than elevators or escalators.<br />

Walking loops in parks, outdoor gyms, and<br />

mixed land use with residential activities near<br />

public facilities will also encourage walking and<br />

exercise. Ideally, according to WHO Europe, cities<br />

also provide accessible spaces for exercise<br />

such as football pitches, tennis courts, or running<br />

routes. Importantly, urban design alone<br />

will not be enough to motivate people to move<br />

more. Intrinsic motivation is key here, and this,<br />

according to a sports psychologist from the<br />

Sports University in Cologne, depends on<br />

whether a sport is fun for the person doing it.<br />

Example: Outdoor group sports are popular<br />

in many big cities. They take place on the beach,<br />

in a park, or in public spaces. Yoga and Zumba<br />

classes, for example, can foster social relationships,<br />

improve physical health, and counteract<br />

mental health risks. Importantly, these classes<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 033

What Would<br />

the Ultimate<br />

Child-Friendly<br />

City Look Like?<br />

LAURA LAKER<br />

046 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

work-life city<br />

Photo: Fineas Anton via Unsplash<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 047

The reality for many urban children is too much time spent indoors playing on<br />

smartphones – but a few cities are fighting the tide with innovative ways to<br />

keep kids healthy, sociable – and outdoors.<br />

Imagine you are 10 years old. You live in a medium-sized city and want<br />

to visit your best friend, a five-minute walk away, so you can go to the<br />

park, another 10 minutes’ walk. The problem is, there’s a big, dangerous<br />

road between you and your friend, and another between them and the<br />

park. You ask your parents if you can walk, they say no, and they are too<br />

busy to take you there themselves. Perhaps you SnapChat your friend<br />

instead, perhaps you play a video game on the sofa. You’ve lost out on<br />

exercise and time outside, interacting with your neighbourhood and, of<br />

course, play time with your friend. This is the reality for many kids today<br />

– but it doesn’t have to be this way. Tim Gill, the author of No Fear:<br />

Growing Up in a Risk Averse Society, says a child-friendly city is one that<br />

allows “everyday freedoms”, so a child can spread their wings as they<br />

grow. “It’s not enough to just talk about playgrounds and nice, pretty<br />

public spaces,” says Gill. That, he says, creates “play ghettoes – places they<br />

have to be taken to by adults”. Society’s mistake, argues Gill, is that our<br />

planning systems are geared around cars, housebuilding and the economy<br />

– rather than the environment, health and quality of life. “You won’t<br />

find any urban planners who disagree with that,” says Gill. “It’s because<br />

our decision-makers are short-termist politicians who don’t need to look<br />

beyond the next two or three years.” A recent report from Arup identifies<br />

five challenges for urban children: traffic and pollution; high-rise living<br />

and urban sprawl; crime, social fears and risk aversion; isolation and<br />

intolerance; and inadequate and unequal access to the city. But in urban<br />

neighbourhoods around the world, child-friendly design is gaining<br />

momentum: from community-led projects, using paint and planters to<br />

tackle dangerous routes to schools and playgrounds, to citywide policy<br />

reimagining housing policies and neighbourhoods for children.<br />

Tirana: trust the silent majority<br />

“Don’t underestimate the power of children,” says Tirana’s young mayor,<br />

Erion Veliaj. After a survey showed the city’s parents spend more on their<br />

cars than their children, Veliaj has used this statistic as moral leverage to<br />

refocus priorities. In a city short on funds, businesses have sponsored the<br />

transformation of kindergartens and nurseries from run-down “prison<br />

cells” into beautiful spaces, with 10 new ones on the way via public-private<br />

partnerships. Repeated traffic closures on the huge Skanderbeg<br />

Square for play convinced residents to accept it as a permanent car-free<br />

space. Every three months the pedestrian zone expands by one more<br />

street, until the city centre eventually goes completely car-free. PM10 pollutants<br />

have already dropped by 15%. Change isn’t always easy in a city<br />

where the car is a potent status symbol. The construction of a large playground<br />

at Tirana’s artificial lake attracted protests, some of them violent.<br />

“A vocal minority who are well-connected, with vested interests, will<br />

make a lot of noise,” says Veliaj. “You have to trust that the silent majority<br />

will turn up when it opens.” And they did. In his first year Veliaj took<br />

40,000 sq m of land from illegal developments, making way for 31 new<br />

playgrounds. Change isn’t always easy in a city where the car is a potent<br />

status symbol. The construction of a large playground at Tirana’s artificial<br />

lake attracted protests, some of them violent. “A vocal minority who are<br />

well-connected, with vested interests, will make a lot of noise,” says Veliaj.<br />

048 <strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong>

work-life city<br />

“You have to trust that the silent majority will turn up when it opens.” And<br />

they did. In his first year Veliaj took 40,000 sq m of land from illegal developments,<br />

making way for 31 new playgrounds. A city forest ring is populated<br />

by kids’ “birthday trees”, which families plant at given locations.<br />

“When other countries are talking about walls, we are building a wall of<br />

trees, to oxygenate the city,” Veliaj says. About 60% of trees are provided by<br />

citizens and businesses, which plant two per company car. A further city<br />

ring for walking, cycling and public transport is on its way. Tirana also<br />

boasts a “city council for kids”, where young representatives meet the mayor,<br />

debate and take their findings back to school. The great thing about<br />

kids, Veliaj says, is they have no hidden agenda – and they are the best<br />

advocates to persuade their parents to recycle, walk and bike to school.<br />

Rotterdam: wild spaces for kids<br />

Voted the least attractive city to grow up in in 2006, Rotterdam has since<br />

spent 15m (£13.2m) on improvements to public spaces, housing and safe<br />

traffic routes in lower income neighbourhoods in an effort to build a<br />

child-friendly city. An open space in a city park forest has been converted<br />

into a nature playground – Natuurspeeltuin de Speeldernis – giving children<br />

the opportunity for unstructured play. Kids can enjoy the biodiversity<br />

of “wild” space, build dens, fires and rafts, and camp out. It now<br />

draws 35,000 visitors a year. Some school playgrounds have been turned<br />

into community squares – featuring high-quality playable spaces with<br />

anything from community gardening to sporting facilities, allowing kids<br />

to experience life within the wider community. Historically a city with<br />

high levels of social housing, Rotterdam has embarked on an unashamed<br />

programme of state-sponsored gentrification. The city’s Promising Places<br />

scheme builds on earlier work in a bid to retain wealthier, highly educated<br />

young families. Hundreds of new, detached family homes are being<br />

built in districts around the city centre – with plenty of green space, play<br />

areas and a target of two excellent-rated schools per district. Previously<br />

rented properties are being sold off in promising areas, and families given<br />

support for home improvements. A community Droomstraat (dream<br />

streets) programme, allows residents to bid for and design street improvements,<br />

swapping traffic and car parking for things such as vegetable<br />

patches or public seating. The improvements seem to be working: the city<br />

reports that people are now staying in Rotterdam with their families, and<br />

developers are keen to build new homes.<br />

Bogotá: mapping danger spots<br />

The former mayor of Bogotá, Enrique Peñalosa, once said: “Children are<br />

a kind of indicator species. If we can build a successful city for children,<br />

we will have a successful city for everyone.” Work to make the city’s public<br />

spaces more equitable started two decades ago with Peñalosa’s ambitious<br />

bus rapid transit scheme, bike lanes, and the introduction of 1,200<br />

parks and play spaces. In one of the city’s poorest districts, Ciudad Bolívar,<br />

community members have been working with Urban 95, a Bernard van<br />

Leer Foundation initiative to improve public space for people under<br />

95cm tall. In a district with high crime rates and little green space, a community<br />

walk-around identified danger spots and how residents would<br />

<strong>topos</strong> <strong>122</strong> 049