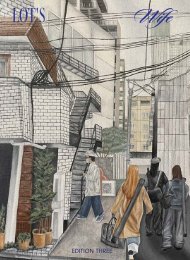

Lot's Wife Edition 8 2013

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SUBHEADING<br />

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT AND<br />

AFRICAN STATES:<br />

A Troubled Relationship<br />

Tamara Preuss<br />

The birth of the International Criminal Court (ICC) was hailed around<br />

the world as a victory for international justice. It was hoped that its<br />

creation would spell the end of impunity for individuals guilty of the<br />

worst crimes known to the international community.<br />

The ICC was created by an international treaty known as the<br />

Rome Statute in 1998. The Court is historically unique as it is the first<br />

permanent international criminal court. The court exercises jurisdiction<br />

over three crimes; namely, war crimes, crimes against humanity and<br />

genocide. Currently, 122 states are party to the Rome Statute with the<br />

notable exceptions of the United States, China, Russia and Israel.<br />

In spite of the admirable aspirations that lead to the foundation<br />

of the Court it has been plagued with problems concerning state<br />

cooperation, funding and legitimacy. The Court’s relationship with the<br />

African Union (AU) and the 34 African states that are party to the<br />

Rome Statute has been particularly problematic.<br />

At an extraordinary summit of the AU, which took place on<br />

the 11-12th of October, AU states considered the future direction of<br />

their relationship with the ICC. The state parties declared that no<br />

sitting government officials should be brought before the ICC, a direct<br />

contradiction to the Rome Statute. They also requested that the ICC<br />

defer the case against the Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta.<br />

The long-term success of the Court depends on whether it can<br />

resolve its issues with the AU and African states and regain legitimacy as<br />

an arbiter of international justice.<br />

One charge that has been consistently leveled at the Court is that<br />

it is unfairly biased against Africans. All of the cases currently before<br />

the Court involve individuals of an African nationality. The AU argues<br />

that the ICC targets Africans and ignores atrocities committed in other<br />

regions.<br />

The AU’s argument ignores the fact that the Court may only<br />

consider a case where the national court of the accused is unable or<br />

unwilling to do so. This implies a situation in which a state’s judicial<br />

system has either collapsed or sided with the accused. Arguably, this<br />

occurs disproportionately in African states hence the overrepresentation<br />

of African individuals at the Court. Indeed, four of the eight situations<br />

currently being considered by the Court were referred by the state itself.<br />

Nevertheless, the ICC should take the AU’s concerns seriously.<br />

The declaration that no sitting head of state should appear before the<br />

ICC severely limits its capacity to deliver justice.<br />

In particular, two cases have incited disagreement between the AU<br />

and the ICC. These are the indictments of Sudanese President Omar<br />

al-Bashir and the Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta.<br />

Al-Bashir was indicted in 2009 for his alleged role in atrocities<br />

committed in Darfur following a referral of the situation to the ICC by<br />

the United Nations Security Council. AU member states agreed to not<br />

enforce al-Bashir’s arrest warrant if he were to visit their country and<br />

they unsuccessfully petitioned the Court to defer the case. They argued<br />

that the need to resolve the conflict in Darfur should take precedence<br />

over justice.<br />

The concerns of the AU bring to the fore the issue that sometimes<br />

peace and justice are irreconcilable. From the AU’s perspective, the<br />

indictment provides an incentive for al-Bashir to cling to power, as<br />

amnesty is no longer a possibility. Should the international community<br />

place more importance on the punishment of a few individuals than a<br />

peace agreement that could resolve a long and bitter civil conflict? The<br />

ICC has firmly decided in favour of this proposition; however perhaps<br />

they should reconsider their position. In some situations, the ICC should<br />

allow a society embroiled in civil conflict the chance to establish peace<br />

before indicting those responsible for international crimes.<br />

The ICC indicted the current President of Kenya, Uhuru<br />

Kenyatta, in 2011 for his alleged role in the violence that followed the<br />

2007 Kenyan presidential election. In response, the Kenyan National<br />

Assembly passed a motion to withdraw Kenya from the Rome Statute<br />

and petitioned the United Nations Security Council to defer the<br />

case. Kenyatta has thus far cooperated with proceedings but there is<br />

speculation that he will not appear at The Hague when his trial starts on<br />

12 November <strong>2013</strong>. The fact that Kenyatta was democratically elected<br />

whilst facing trial by the ICC shows that a majority of Kenyans do not<br />

support the trial.<br />

The ICC must improve its relationship with Africa if it is to retain<br />

legitimacy as an international arbiter of justice. Just how this may be<br />

achieved is difficult to determine. The ICC’s past attempts to establish<br />

an African liaison office have been rejected by the AU but they must<br />

persist. The Court must actively engage with African governments<br />

to build relationships based on trust and understanding. In addition,<br />

the Court must recognise that in some situations peace must is more<br />

important than justice.<br />

LOT’S WIFE EDITION 8 • <strong>2013</strong><br />

21