Differential subject marking in Polish: The case of Genitive vs ...

Differential subject marking in Polish: The case of Genitive vs ...

Differential subject marking in Polish: The case of Genitive vs ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

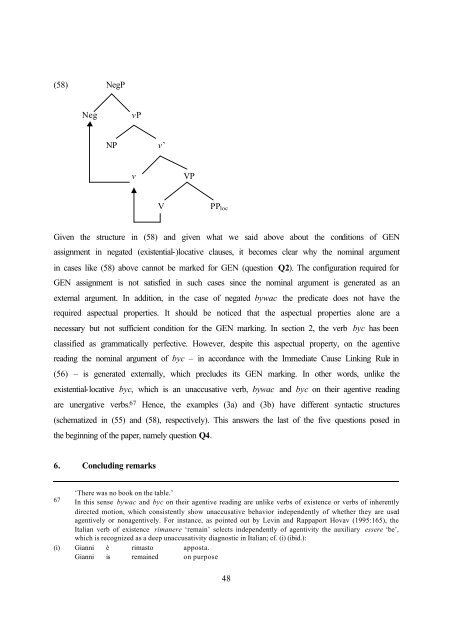

(58) NegP<br />

Neg vP<br />

NP v’<br />

v VP<br />

V PPloc<br />

Given the structure <strong>in</strong> (58) and given what we said above about the conditions <strong>of</strong> GEN<br />

assignment <strong>in</strong> negated (existential-)locative clauses, it becomes clear why the nom<strong>in</strong>al argument<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>case</strong>s like (58) above cannot be marked for GEN (question Q2). <strong>The</strong> configuration required for<br />

GEN assignment is not satisfied <strong>in</strong> such <strong>case</strong>s s<strong>in</strong>ce the nom<strong>in</strong>al argument is generated as an<br />

external argument. In addition, <strong>in</strong> the <strong>case</strong> <strong>of</strong> negated bywac the predicate does not have the<br />

required aspectual properties. It should be noticed that the aspectual properties alone are a<br />

necessary but not sufficient condition for the GEN <strong>mark<strong>in</strong>g</strong>. In section 2, the verb byc has been<br />

classified as grammatically perfective. However, despite this aspectual property, on the agentive<br />

read<strong>in</strong>g the nom<strong>in</strong>al argument <strong>of</strong> byc – <strong>in</strong> accordance with the Immediate Cause L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Rule <strong>in</strong><br />

(56) – is generated externally, which precludes its GEN <strong>mark<strong>in</strong>g</strong>. In other words, unlike the<br />

existential-locative byc, which is an unaccusative verb, bywac and byc on their agentive read<strong>in</strong>g<br />

are unergative verbs. 67 Hence, the examples (3a) and (3b) have different syntactic structures<br />

(schematized <strong>in</strong> (55) and (58), respectively). This answers the last <strong>of</strong> the five questions posed <strong>in</strong><br />

the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the paper, namely question Q4.<br />

6. Conclud<strong>in</strong>g remarks<br />

‘<strong>The</strong>re was no book on the table.’<br />

67 In this sense bywac and byc on their agentive read<strong>in</strong>g are unlike verbs <strong>of</strong> existence or verbs <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>herently<br />

directed motion, which consistently show unaccusative behavior <strong>in</strong>dependently <strong>of</strong> whether they are used<br />

agentively or nonagentively. For <strong>in</strong>stance, as po<strong>in</strong>ted out by Lev<strong>in</strong> and Rappaport Hovav (1995:165), the<br />

Italian verb <strong>of</strong> existence rimanere ‘rema<strong>in</strong>’ selects <strong>in</strong>dependently <strong>of</strong> agentivity the auxiliary essere ‘be’,<br />

which is recognized as a deep unaccusativity diagnostic <strong>in</strong> Italian; cf. (i) (ibid.):<br />

(i) Gianni è rimasto apposta.<br />

Gianni is rema<strong>in</strong>ed on purpose<br />

48