Chapter 5 Feeding Ecology of the Australian Raven on Rottnest Island

Chapter 5 Feeding Ecology of the Australian Raven on Rottnest Island

Chapter 5 Feeding Ecology of the Australian Raven on Rottnest Island

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

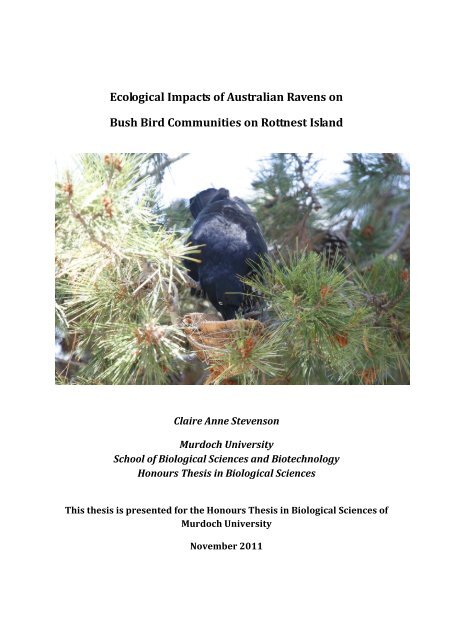

Ecological Impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong><br />

Bush Bird Communities <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong><br />

Claire Anne Stevens<strong>on</strong><br />

Murdoch University<br />

School <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biological Sciences and Biotechnology<br />

H<strong>on</strong>ours Thesis in Biological Sciences<br />

This <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis is presented for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> H<strong>on</strong>ours Thesis in Biological Sciences <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Murdoch University<br />

November 2011

COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGEMENT<br />

I acknowledge that a copy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis will be held at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Murdoch University Library.<br />

I understand that, under <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> provisi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> s51.2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Copyright Act 1968, all or part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis may be copied without infringement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> copyright where such a reproducti<strong>on</strong> is for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

purposes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> study and research.<br />

This statement does not signal any transfer <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> copyright away from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> author.<br />

Signed: …………………………………………………………...<br />

Full Name <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Degree: …………………………………………………………………...<br />

Thesis Title: Ecological Impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> Bush Bird Communities <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong><br />

Author: Claire Anne Stevens<strong>on</strong><br />

Year: 2011

Abstract<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> Corvus cor<strong>on</strong>oides is a predator <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> eggs and nestlings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, Western Australia. Nest predati<strong>on</strong> is a threatening process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> island<br />

birds, and when combined with o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r threatening processes, such as habitat fragmentati<strong>on</strong><br />

and degradati<strong>on</strong>, sustained nest predati<strong>on</strong> can cause declines in bush bird communities. The<br />

terrestrial habitats <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> have been historically fragmented through land<br />

clearing, so c<strong>on</strong>cern was raised by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority regarding <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> bush bird communities. The aims <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study were to describe <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, in particular <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> feeding ecology, and to<br />

evaluate how important bush birds are in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> diet <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

To determine <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nest predati<strong>on</strong> by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g>, an artificial nest<br />

experiment was c<strong>on</strong>ducted over four m<strong>on</strong>ths from August to November, over six study sites.<br />

The diet <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> was analysed by laboratory examinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> raven stomach<br />

samples. In additi<strong>on</strong>, observati<strong>on</strong>al data collected at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study sites during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study period<br />

was used to quantify <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> behaviour, abundance and distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ravens, and compared to<br />

bush bird distributi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>.<br />

During this study, ravens predated 20% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> artificial nests, indicating a high capacity for<br />

potential populati<strong>on</strong> impacts. Nest predati<strong>on</strong> was c<strong>on</strong>firmed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> presence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

stomach c<strong>on</strong>tents <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ravens from <strong>Rottnest</strong>, but plant material and invertebrates were found<br />

to be more important in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> diet. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> prefers <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> disturbed and urban<br />

habitat areas <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> for feeding, roosting and breeding. Bush birds avoid <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se<br />

areas, and prefer remnant and revegetated areas.<br />

The results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study have identified <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> as a potential predator <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

nesting bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>. However, restorati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> island vegetati<strong>on</strong> may be<br />

having a positive effect <strong>on</strong> bush bird communities that outweighs losses <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> eggs and<br />

nestlings to ravens. In view <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se results, c<strong>on</strong>tinued management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> raven<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> is recommended as a precauti<strong>on</strong>ary approach so that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nest<br />

predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> bush birds are limited. Meanwhile, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> dynamics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> selected bush<br />

i

irds can be assessed to c<strong>on</strong>firm that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y are recovering in resp<strong>on</strong>se to habitat restorati<strong>on</strong><br />

programs.<br />

ii

C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

Acknowledgements vii<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> 1<br />

1.1 What are bush birds? 2<br />

1.2 Why is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> a pest? 3<br />

1.3 Research questi<strong>on</strong>s 4<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 Terrestrial Avifauna <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 7<br />

2.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> and Aims 7<br />

2.1.1 Geography and geology 7<br />

2.1.2 History 8<br />

2.1.3 Vegetati<strong>on</strong> 9<br />

2.2 Methods 15<br />

2.2.1 Literature review 15<br />

2.2.2 Study area and observati<strong>on</strong>s 15<br />

2.3 Results 17<br />

2.3.1 History <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> Avifauna 17<br />

Decreases 17<br />

Increases 22<br />

2.3.2 Species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cern 23<br />

2.3.3 Distributi<strong>on</strong> and abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds 23<br />

2.4 Discussi<strong>on</strong> 26<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 Biology and <str<strong>on</strong>g>Ecology</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 29<br />

3.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> and Aims 29<br />

3.1.1 Tax<strong>on</strong>omy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> corvids 29<br />

3.1.2 Life history <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> 30<br />

3.1.3 The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> as a pest 31<br />

3.1.4 History <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ravens <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 32<br />

3.2 Methods 33<br />

3.2.1 Field observati<strong>on</strong> 33<br />

3.2.2. Laboratory analysis 34<br />

3.3. Results 37<br />

3.3.1 Distributi<strong>on</strong> and abundance 37<br />

3.3.2 Behaviour and activity 40<br />

3.3.3 Breeding 41<br />

iii

3.3.4 Demographics 43<br />

Sex, age and breeding c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> 44<br />

Morphology 44<br />

Weights 44<br />

3.3.5 Parasitology 45<br />

3.4 Discussi<strong>on</strong> 45<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 4 Nest Predati<strong>on</strong> by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 49<br />

4.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> and Aims 49<br />

4.1.1 Nest predati<strong>on</strong> by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> 49<br />

4.1.2 Predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 50<br />

4.1.3 Hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ses tested 51<br />

4.2 Methods 52<br />

4.2.1 Artificial nest experiments: uses and criticisms 52<br />

4.2.2 Artificial nest c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> 53<br />

4.2.3 Artificial egg c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> 55<br />

4.2.4 Bait eggs 56<br />

4.2.5 Site selecti<strong>on</strong> 56<br />

4.2.6 M<strong>on</strong>itoring <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> artificial nests 57<br />

4.2.7 Statistical analysis 58<br />

4.2.8 C<strong>on</strong>trol – naturally occurring nests 59<br />

4.3 Results 59<br />

4.3.1 Identificati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predators 59<br />

4.3.2 Predati<strong>on</strong> intensity 60<br />

4.3.3 Test <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> specific hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ses 62<br />

Hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis 1(i) Predati<strong>on</strong> versus site 62<br />

Hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis 1(ii) Predati<strong>on</strong> versus distance from settlement<br />

62<br />

Hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis 1(iii) Predati<strong>on</strong> versus abundance 63<br />

Hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis 2 Predati<strong>on</strong> versus nest exposure 64<br />

Hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>sis 3 Predati<strong>on</strong> versus nest type 64<br />

4.3.4 Active natural nests 64<br />

4.4 Discussi<strong>on</strong> 64<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Feeding</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 69<br />

5.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> and Aims 69<br />

5.1.1 Diet <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> 69<br />

5.2 Methods 70<br />

5.2.1 Field observati<strong>on</strong>s 70<br />

iv

5.2.2 Laboratory examinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> stomach c<strong>on</strong>tents 70<br />

5.3 Results 72<br />

5.3.1 Foraging behavior and food source 72<br />

5.3.2 Food types and importance 76<br />

5.4 Discussi<strong>on</strong> 78<br />

6 General Discussi<strong>on</strong> 80<br />

6.1 Outcomes for this study 81<br />

6.1.1 Questi<strong>on</strong> 1 81<br />

6.1.2 Questi<strong>on</strong> 2 81<br />

6.1.3 Questi<strong>on</strong> 3 82<br />

6.1.4 Questi<strong>on</strong> 4 82<br />

6.2 Questi<strong>on</strong> 5 83<br />

6.3 Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for future research 84<br />

6.4 Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for raven management 86<br />

6.5 C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> 88<br />

Appendices<br />

Appendix I Characteristics and placement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> artificial nests and<br />

predati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong> by nest number 91<br />

Appendix II Summary: Nest predati<strong>on</strong> by trip 98<br />

Appendix III Summary: Nest predati<strong>on</strong> by site 99<br />

Appendix IV Summary: Nest predati<strong>on</strong> by nest type 100<br />

Appendix V Summary: Nest predati<strong>on</strong> by exposure 101<br />

References 102<br />

v

List <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Figures<br />

Figure 2.1 <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> in relati<strong>on</strong> to adjacent Swan Coastal Plain showing<br />

key landmarks 6<br />

Figure 2.2a Inset A: Thomps<strong>on</strong> Bay settlement with major roads and landmarks 6<br />

Figure 2.2b <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> with topographical features and infrastructure,<br />

including study site locati<strong>on</strong>s 7<br />

Figure 2.3 Major vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> as <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2010 12<br />

Figure 2.4 Distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> six bush bird species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cern<br />

compared to two invasive species 23<br />

Figure 2.5 Combined m<strong>on</strong>thly frequency and distributi<strong>on</strong> by site <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds 24<br />

Figure 3.1 Age characteristics <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> from <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 34<br />

Figure 3.2 Distributi<strong>on</strong> and total frequency <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 35<br />

Figure 3.3 Mean +/- standard deviati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> frequency <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> raven sightings per<br />

m<strong>on</strong>th by site 37<br />

Figure 3.4 Average daily number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ravens proporti<strong>on</strong>ed by site 39<br />

Figure 4.1 Artificial nest designs 50<br />

Figure 4.2 Imprints made by <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> clay egg and bait egg 54<br />

Figure 4.3 Predati<strong>on</strong> compared to abundance by m<strong>on</strong>th 57<br />

Figure 4.4 Linear regressi<strong>on</strong> test relating predati<strong>on</strong> intensity to distance<br />

from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> settlement 59<br />

Figure 5.1 Sources <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> food in foraging <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 66<br />

Figure 5.2 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> foraging behaviours 68<br />

List <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tables<br />

Table 2.1 Field site locati<strong>on</strong>s and habitat descripti<strong>on</strong> 14<br />

Table 2.2 Literature review: terrestrial avifauna <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> 17<br />

Table 3.1 Morphological characteristics 32<br />

Table 3.2 Demographics and morphological measurements 41<br />

Table 4.1 Status <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nests predated by predator 56<br />

Table 4.2 Average daily rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong> by site for each m<strong>on</strong>th 57<br />

Table 5.1 Index <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> relative importance 70<br />

vi

Acknowledgements<br />

My sincerest thanks to my supervisor A/Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Mike Calver who took a chance to take me <strong>on</strong> as a<br />

student, and has steered me through <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last two years, keeping me focused and my ideas <strong>on</strong> track. I<br />

would also like to extend heartfelt thanks to Dr. Ric How, who without his encouragement and<br />

guidance this would not have been possible.<br />

I would like to thank <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority for funding <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> project, travel and<br />

accommodati<strong>on</strong> support, and provisi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> research permits for field work. In particular I would like<br />

to thank Helen Shortland-J<strong>on</strong>es and R<strong>on</strong> Preimus for assisting me while in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> field, helping with my<br />

enquiries and supplying me with fresh raven carcasses. I hope this document helps you manage<br />

those pesky ravens! Thanks to David Roberts<strong>on</strong> for providing shapefiles and licences to use <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> GIS<br />

data. Birds Australia Western Australia (BAWA) generously provided <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> data from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir <strong>Rottnest</strong><br />

<strong>Island</strong> bird surveys. I would especially like to thank Sue Ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r for her support and helping me with<br />

any enquiries I had regarding <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> BAWA project.<br />

This project was supported in kind by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Western <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> Museum. I would like to thank R<strong>on</strong><br />

Johnst<strong>on</strong>e for helping me with background data, references and his insights. Also, a big thanks to my<br />

team mates Brad, Paul, Linette, Bec, Tom and Salvador, and all <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r staff who had to endure<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sight and smell <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> raven carcasses. Many o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r people gave <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir support and assistance and I<br />

thank you all. In particular, Graeme Fult<strong>on</strong> for kindly <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fering his time to share his experiences and<br />

knowledge <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> artificial nest experiments; Dr Alan Lymbery <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Murdoch University for parasite<br />

identificati<strong>on</strong>s; Dr. Rob Davis, A/Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Darryl J<strong>on</strong>es and Dr. Leo Joseph for helping source references.<br />

Finally, I would like to thank my ever patient family and awesome friends. Thanks to Emma, my Mum<br />

and Dad for driving me and my gear to and from ferry terminals, and looking after my pets. Massive<br />

thanks to Mat Darch for keeping me sane and all <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> hugs, without you it would have been so much<br />

harder. Thanks to Gizmo and Widget for sleeping <strong>on</strong> my references and keeping me company late at<br />

night. Sorry kitties. It’s time to put <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> books away.<br />

vii

viii

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1<br />

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

The 2011 Acti<strong>on</strong> Plan for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> Birds (Garnett, Szabo and Dust<strong>on</strong> 2011 ) lists 11.8% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds as threatened, with an additi<strong>on</strong>al 2.2% listed as extinct. Fifty-eight percent<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> threatened or extinct bird taxa in Australia are found <strong>on</strong> islands (Burbidge 2010).<br />

<strong>Island</strong> birds are threatened by habitat destructi<strong>on</strong> and modificati<strong>on</strong>, exploitati<strong>on</strong> by humans<br />

(hunting), fire, introduced species and direct predati<strong>on</strong> from vertebrate animals (Hopkins<br />

and Harvey 1989; Whittaker and Fernandez-Palacois 2007; Garnett et al. 2011). In additi<strong>on</strong>,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds are facing widespread decline (Barrett, Ford and Recher 1994; Recher<br />

1999). The major threatening processes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds are habitat fragmentati<strong>on</strong> resulting<br />

from human management processes and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> associated c<strong>on</strong>sequences such as fire, change<br />

in species assemblage, increased edge effects, increased competiti<strong>on</strong> and increased<br />

predati<strong>on</strong> (Mac Nally and Bennett 1997). The coastal islands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Western Australia can<br />

provide sanctuary for plants and animals, including bush birds, from some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> events that<br />

threaten populati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mainland (Burbidge 1989), but <strong>on</strong>ly if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> islands <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>mselves<br />

are protected from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se processes.<br />

<strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> has had a l<strong>on</strong>g history <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> land clearing for agricultural and urban<br />

development resulting in substantial habitat loss and fragmentati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> remaining<br />

habitat. Subsequently, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> avifauna <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island has changed dramatically with two bush<br />

bird species becoming locally extinct and several o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rs declining. Several o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species<br />

have invaded and col<strong>on</strong>ized as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat has become suitable. One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> most successful<br />

col<strong>on</strong>izers has been <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> Corvus cor<strong>on</strong>oides. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> is listed<br />

by Barrett, Ford and Recher (1994) as a species that is ‘tolerant <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fragmentati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

disturbance’. The proliferati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> raven from human induced causes may negatively<br />

impact <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r bush bird species (see Recher 1999). Bird species groups that<br />

have declined regi<strong>on</strong>ally since European settlement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australia, and that have also declined<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, include whistlers (Pachycephalidae), thornbills, geryg<strong>on</strong>es<br />

1

(Acanthizidae), robins (Petroicidae) and small h<strong>on</strong>eyeaters (Meliphagidae)(Catterall et al.<br />

1998).<br />

Nest predati<strong>on</strong> is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> greatest cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nesting mortality in birds (Skutch 1966; Ricklefs<br />

1969, Ford et al. 2001). Nest predati<strong>on</strong> increases in fragmented habitats (Andren 1992;<br />

Piper and Catterall 2004), as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat becomes more exposed and as predators move in<br />

from neighboring areas. Bird populati<strong>on</strong>s in fragmented habitats that are subjected to<br />

extensive nest predati<strong>on</strong> are unlikely to be self-sustaining (Schmidt and Whelan 1999).<br />

Avian predators have been identified as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> most important nest predators <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds<br />

(Fult<strong>on</strong> and Ford 2001; Piper, Catterall and Olsen 2002; Zanette 2002). The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

has been identified as a predator <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r bush bird nests (Major et al. 1994; Major et al.<br />

1999; Fult<strong>on</strong> 2006), but I am unaware <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any detailed study c<strong>on</strong>ducted into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

nest predati<strong>on</strong> by this species.<br />

1.1 What are bush birds?<br />

The term bush bird, or woodland bird, arouses an image <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a small, delicate, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten n<strong>on</strong>-<br />

descript passerine (s<strong>on</strong>g bird), but <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> category can be applied to all birds that occur in n<strong>on</strong>-<br />

aquatic habitats such as woodlands, scrublands, grasslands, forests and heath. “Bush bird”<br />

also includes larger passerines such as bowerbirds, magpies and corvids; as well as<br />

terrestrial n<strong>on</strong>-passerines for example quails, parrots, raptors, cuckoos and owls. For <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

c<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study I refer to a bush bird to include those species that prefer, for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> most<br />

part, terrestrial habitats including vegetati<strong>on</strong> fringing water bodies and coastal dunes and<br />

heath. I do not include shorebirds (waders), ducks, gulls, rails, her<strong>on</strong>s and egrets as bush<br />

birds despite that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds may also use terrestrial habitats for foraging,<br />

nesting or roosting. I have selected six passerine bush birds resident <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> as a<br />

focus for this study: White-browed Scrubwren Sericornis fr<strong>on</strong>talis; Western Geryg<strong>on</strong>e<br />

Geryg<strong>on</strong>e fusca, Singing H<strong>on</strong>eyeater Lichenostomus virescens, White-fr<strong>on</strong>ted Chat<br />

Epithianura albifr<strong>on</strong>s; Red-caped Robin Petroica goodenovii , and Golden Whistler<br />

Pachycephala pectoralis. These species have been identified as those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>cern (Saunders and de Rebeira 2009) <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>.<br />

2

1.2 Why is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> a pest?<br />

Invasive animals are those that have increased in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir distributi<strong>on</strong> and abundance as a<br />

result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘human activities’ (Olsen, Silcocks and West<strong>on</strong> 2006). When <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> species has<br />

increased so significantly that it causes harm to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> envir<strong>on</strong>ment, o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species, agriculture<br />

or infrastructure, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> species is c<strong>on</strong>sidered a pest. In Australia, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> terms “invasive” and<br />

“pest” are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten associated with introduced mammalian predators such as cats, foxes and<br />

rabbits. Native animals can also be c<strong>on</strong>sidered pests when <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘… changing land use has<br />

resulted in overabundant populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> some species or <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> gregarious<br />

species in a particular area’ (Hart and Bomford 2006). In southwestern Australia, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> has expanded its range and now occurs <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, where it has<br />

become both overabundant and c<strong>on</strong>centrated.<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> was identified as pest bird under <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority Pest<br />

Management Plan (2008) because it is a ‘nuisance to visitors and island residents’, in<br />

particular around <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> settlement area where it competes for human food scraps with Silver<br />

Gulls Larus novaehollandiae and peafowl. In additi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re is c<strong>on</strong>cern that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> may be predating <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nests <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>. The Pest<br />

Management Plan identified <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> need for research into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> diet <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g>, in<br />

particular through <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> stomach c<strong>on</strong>tents.<br />

The l<strong>on</strong>g-term goal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pest Management Plan is: ‘To have a sustainable populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

ravens <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> that feed <strong>on</strong> natural food resources instead <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> human waste’.<br />

<strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority has initiated raven management by including processes to reduce<br />

access by ravens to human food scraps in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Waste Management Plan; by c<strong>on</strong>tinuing<br />

educati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> public and residents to deter interacti<strong>on</strong> with ravens; and by targeted<br />

reducti<strong>on</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> raven populati<strong>on</strong> through culling. The outcomes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this study will be used<br />

to decide <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> future c<strong>on</strong>trol methods and management initiatives <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>.<br />

3

1.3 Research Questi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

The overall aim for this study is to describe <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong><br />

<strong>Island</strong>. In particular, I will assess whe<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> is a predator <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nesting bush<br />

birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, and how this impacts <strong>on</strong> bush bird communities.<br />

Specific questi<strong>on</strong>s are:<br />

1) What is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>?<br />

2) What is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> abundance and distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>?<br />

3) Does <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> predate <strong>on</strong> bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>?<br />

4) What is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> feeding ecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>?<br />

5) How does predati<strong>on</strong> by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> impact <strong>on</strong> bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong><br />

<strong>Island</strong>?<br />

I use observati<strong>on</strong>al and experimental methods to investigate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se questi<strong>on</strong>s. The research<br />

is presented here with each questi<strong>on</strong> answered in an independent chapter. The findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

each chapter are linked in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> final Discussi<strong>on</strong> (<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 6) where I will answer Questi<strong>on</strong> 5.<br />

The chapters are described below:<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 Reviews <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> history <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> and describes <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> changes to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

avifauna through a literature review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> published surveys <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong><br />

avifauna over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last 100 years;<br />

Examines <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> current distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> using<br />

observati<strong>on</strong>al data collected during this study and external data sources.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3 Introduces <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> biology and ecology, in particular <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> distributi<strong>on</strong> and<br />

abundance, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> using<br />

observati<strong>on</strong>al data collected during this project.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 4 Investigates nest predati<strong>on</strong> by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> using an artificial nest<br />

experiment.<br />

4

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 Investigates <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> feeding ecology and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> diet <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Raven</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> through observati<strong>on</strong>al data recorded during this study;<br />

Quantifies <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> stomach samples from raven specimens collected<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>.<br />

5

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Chapter</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2<br />

Terrestrial Avifauna <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong><br />

2.1 Introducti<strong>on</strong> and Aims<br />

Since its occupati<strong>on</strong> by European settlers almost 200 years ago, <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> has been<br />

coveted for its natural beauty and idealised lifestyle. As a result, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> natural and<br />

anthropogenic histories are well documented. Many residents <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Perth are sentimental<br />

about <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> envir<strong>on</strong>ment and its recreati<strong>on</strong> opportunities. However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island has<br />

not always been a place for locals and tourists looking to relax. <strong>Rottnest</strong> was formerly used<br />

as a pastoral lease, penal outpost and later a military base, which al<strong>on</strong>g with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> more<br />

recent development <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> facilities for tourists, has c<strong>on</strong>siderably changed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> compositi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> flora and fauna species. It no l<strong>on</strong>ger resembles what would have been experienced by<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first settlers in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1830s.<br />

In this chapter I summarize <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> history <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> and examine how <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> changes to<br />

vegetati<strong>on</strong> and landscape use have influenced <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> distributi<strong>on</strong> and abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds.<br />

The changes in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> status <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> is examined through a review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> literature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> previous bird studies and historical records, and is compared to recent<br />

surveys and observati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

2.1.1 Geography & geology<br />

<strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> is located 17km northwest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fshore from Fremantle, Western Australia<br />

(Figure 2.1). The island has a temperate climate, with temperatures slightly lower than<br />

those recorded <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> adjacent mainland, and an average annual rainfall <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 563mm (Bureau<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Metrology 2011). It is part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a chain <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Quaternary limest<strong>on</strong>e islands and reefs al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

c<strong>on</strong>tinental shelf opposite Perth, which also includes those in Cockburn Sound (Garden,<br />

Carnac and Penguin <strong>Island</strong>s) (Playford 1988) to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> south, which were separated from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

mainland approximately 7000 years ago (Glenister, Hassell and Kneeb<strong>on</strong>e 1959). <strong>Rottnest</strong> is<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> largest (1900 ha) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se island and measures 10.5km from east to west. It is<br />

predominantly open heath and dunes with 10% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> area occupied by large salt lakes<br />

separating <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern and western parts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island (Playford 1983).<br />

7

2.1.2 History<br />

Archaeological evidence suggests Aboriginal <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g>s occupied <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> during<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Eocene, but occupati<strong>on</strong> ceased so<strong>on</strong> after <strong>Rottnest</strong> was separated from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

mainland during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> late Pleistocene (Playford 1988; Dortch 1991; Hesp, Murray-<br />

Wallace and Dortch 1999). The local No<strong>on</strong>gar name for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island is Wadjemup meaning<br />

‘place across <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> water’ (Somerville 1976) and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y maintain a spiritual c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island for ancient and recent events. The first Europeans to document <strong>Rottnest</strong><br />

<strong>Island</strong> was <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Dutch explorer Volkersen in 1658, and later followed by Vlaming in 1696-<br />

7 (Somerville 1976). It was not until settlement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Swan River Col<strong>on</strong>y in 1829 that<br />

Europeans also settled <strong>Rottnest</strong>. In 1831, privileged early pi<strong>on</strong>eers were given<br />

allotments <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> land where agriculture was trialed, but <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se failed early <strong>on</strong>. From 1838 to<br />

1904 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island was used as a penal settlement for aboriginal pris<strong>on</strong>ers (Wats<strong>on</strong>, 1998).<br />

The island was developed for tourism in 1907 (Joske, Jeffery and H<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fman 1995) and this<br />

has c<strong>on</strong>tinued to be <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> main use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island, with a short period as a military base<br />

during World War II. The establishment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> recreati<strong>on</strong>al facilities included c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

roads, buildings, amenities, and a golf course northwest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> settlement. Increased<br />

visitati<strong>on</strong> put pressure <strong>on</strong> fisheries and potable water supplies, but strict visitor permits<br />

limited most people to day visits.<br />

The establishment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a military base during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1930s and 1940s fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r changed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

landscape with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> additi<strong>on</strong>al roads, a bituminised water catchment area at<br />

Mt Herschel, supplementary fresh water wells, extensi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> airstrip, fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r clearing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> land for trenches and an increase in fires (Somerville 1976; Playford 1988). Recreati<strong>on</strong><br />

recommenced after <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> World War II with two major infrastructure projects having negative<br />

ecological impacts <strong>on</strong> interior wetlands. Road building during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1970s utilised marl<br />

extracted from five <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> eight swamps, turning <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m from fresh or brackish water to<br />

permanently saline lakes (Playford 1988; Saunders and de Rebeira 2009). Following this a<br />

road was c<strong>on</strong>structed al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn shoreline <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Lake Herschel, removing significant<br />

foraging habitat for wading birds (Saunders and de Rebeira 2009).<br />

Recent management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> islands terrestrial and marine habitats and fauna has been more<br />

favourable to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> biota. The <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority Act 1987 includes<br />

8

in its functi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> protecti<strong>on</strong>, maintenance and repair <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> natural envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

island. In 2009/10 over 356,000 people visited <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, with 65% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> visitors<br />

departing <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same day. The island infrastructure has changed significantly in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last<br />

twenty-five years to support day-visitati<strong>on</strong> with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> provisi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> multiple cafes, restaurants<br />

and take-away outlets, while <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> overnight accommodati<strong>on</strong> has remained<br />

unchanged. Over <strong>on</strong>e t<strong>on</strong>ne <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> waste is produced by visitors annually, and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y require 164<br />

kilolitres <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> potable water and over 500 milli<strong>on</strong> kilowatts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> power (<strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority<br />

2010). To <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fset <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential negative impacts this may have <strong>on</strong> island resources,<br />

sustainability and waste management plans have included <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> installati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a wind turbine<br />

and desalinati<strong>on</strong> plant, as well as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> removal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> waste to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mainland, replacing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>site<br />

infill. Aquatic and terrestrial habitats are protected by signage, fencing or restricted usage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

important ecological areas, and through visitor management and educati<strong>on</strong>. This change<br />

towards preservati<strong>on</strong> for enjoyment instead <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> exploitati<strong>on</strong>, reflects <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> change in attitude<br />

by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> public, and subsequently governments, whereby natural habitats are valued for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir<br />

aes<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>tic and ec<strong>on</strong>omic value, that has been clearly evidenced over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last forty years<br />

(McCormick 1989).<br />

2.1.3 Vegetati<strong>on</strong><br />

Despite <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> close proximity and relatively recent separati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> adjacent<br />

mainland, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetati<strong>on</strong> is markedly different. The differences in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> flora have been<br />

influenced by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> geology, wind exposure and soil structure (McArthur 1957; Storr 1962).<br />

Similar species compositi<strong>on</strong>s exist <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mainland where <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> envir<strong>on</strong>ment is similar. For<br />

example, Callitris preisii remnants occur near Henders<strong>on</strong> and Acacia rostellifera scrub is<br />

found between Trigg and Scarborough. In comparis<strong>on</strong>, <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> flora is lacking in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

dominant tall eucalypt and banksia species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Swan Coastal Plain, although fossil pollen<br />

records shows <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se were <strong>on</strong>ce<br />

9

Figure 2.1: <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> in relati<strong>on</strong> to adjacent Swan Coastal Plain showing key landmarks. GIS<br />

Imaging source used under WALIS Licence for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-commercial use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> land informati<strong>on</strong><br />

10<br />

Figure 2.2a: Inset A Thomps<strong>on</strong> Bay settlement with major roads and landmarks: 1) Bakery;<br />

2) General Store; 3) Dome Café; 4) Hotel <strong>Rottnest</strong>; 5) Aristos Café; 6) Carolyn Thomps<strong>on</strong><br />

campground; 7) Heritage Comm<strong>on</strong>; 8) tennis courts; 9) desalinati<strong>on</strong> plant; 10) bike hire;

provided by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> WA, courtesy WA Museum. 2011. 11) Lancier Street cottages; 12) Fun park<br />

11

Figure 2.2b: <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> with topographical features and infrastructure, and study sites locati<strong>on</strong>s: 1) Bathurst Point, 2) tuart grove near The Basin; 3) Peacock Flats near rubbish tip site, 4)<br />

tuart grove near Garden Lake, 5) Bickley Swamp, 6) revegetati<strong>on</strong> Parker Point Road, S) central Settlement. The urban areas are shaded grey. Figure 2.2a & 2.2b GIS Imaging source used under<br />

WALIS Licence for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-commercial use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> land informati<strong>on</strong> provided by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> WA, courtesy <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority 2011<br />

12

present (Storr, Green and Churchill 1959). Of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se species, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tuart Eucalyptus<br />

gomphocephala has been introduced deliberately, being trialed successfully as a timber<br />

crop and stands are still evident near <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cemetery and Pinky Beach. The vegetati<strong>on</strong><br />

inventory lists 246 plants (vascular flora) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which 42% are exotic species, and are obvious<br />

around <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> urban areas (Rippey, Hislop and Dodd 2003). Moreten Bay fig Ficus macrophylla<br />

and Norfolk <strong>Island</strong> pine Araucaria heterophylla, as well as marlock Eucalyptus platypus, E.<br />

utilis and Casuarina glauca, have been deliberately established for aes<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>tic purposes, with<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> two former species visually dominating <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> settlement. West <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> settlement, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

island vegetati<strong>on</strong> has been shaped drastically over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last two centuries by three major<br />

processes: <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> clearing <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> land by European settlers, changes in fire regimes and changes in<br />

Quokka Set<strong>on</strong>ix brachyurus abundance. These processes appear to have subsequently<br />

modified <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> distributi<strong>on</strong> and abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush bird species <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>.<br />

Early European visitors described <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island vegetati<strong>on</strong> as a dense forest <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cypress Callitris<br />

preissii interspersed with Melaleuca lanceolata and Pittosporum phylliraeoides, with Acacia<br />

rostellifera ‘relatively uncomm<strong>on</strong>’ (Sedd<strong>on</strong> 1983). Following settlement <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern<br />

vegetati<strong>on</strong> was rapidly cleared for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> development <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> agriculture and establishment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

dwellings. The western woodlands were cleared for firewood collecti<strong>on</strong>, with impacts<br />

intensified by grazing stock and an increase in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> frequency <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fires. Evidence from charcoal<br />

deposits found in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sediments <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Barker Swamp (Backhouse 1993) suggest that prior to<br />

European settlement, major fires occurred <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>ce every two centuries<br />

(Rippey and Hobbs 2003) most likely caused by lightning strike. Following settlement, fire<br />

frequency escalated to a weekly event with fire being used as a tool by Aboriginal pris<strong>on</strong>ers<br />

to flush Quokka from vegetati<strong>on</strong> during weekend hunts that occurred until <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> late 1800s<br />

(Somerville 1976). The last major fire in 1955 burnt two-thirds (1800 acres) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island<br />

(Storr 1963; Pen and Green 1983), with a smaller fire in 1997 burning ninety hectares <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

heath between <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> centre and nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn coastline (Rippey and Hobbs 2003). The vegetati<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> has not had sufficient time to adapt to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rapid increase in fire events. Two<br />

species in particular, Callitris preissii and Melaleuca lanceolata, are extremely sensitive to<br />

fire and have been greatly reduced (Baird 1958; Rippey and Hobbs 2003), while Acacia<br />

rostellifera has thrived (Storr 1963) although inhibited by Quokka grazing.<br />

13

Early observers did not document <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Quokka density <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, but it is assumed<br />

that numbers were ‘abundant’ compared to mainland populati<strong>on</strong>s (Storr 1963). The<br />

establishment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> crops and exotic herbivorous plants provided an additi<strong>on</strong>al food source for<br />

Quokkas, but hunting by aboriginal pris<strong>on</strong>ers, vice-regal parties and later tourists, kept <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

populati<strong>on</strong> from proliferating (Storr 1963; Pen and Green 1982). In 1917 <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> species was<br />

declared protected and shooting was prohibited (Rippey et al. 2003). The populati<strong>on</strong><br />

increased rapidly and by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> early 1930s <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y had exploded, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> increase coinciding with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

observed fragmentati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Acacia rostellifera scrub (Storr 1963). Acacia, in particular its new<br />

suckers, are extremely palatable to Quokkas and within two years overgrazing can quickly<br />

remove this species from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> matrix, where it is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n replaced by fire resistant and<br />

unpalatable herbs and low shrubs (Storr et al.1959; Storr 1963).While land clearing and fires<br />

have removed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> melalluca and callitris forests, over grazing by Quokkas<br />

has impeded <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> acacia, leaving <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> dominant vegetati<strong>on</strong> community <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong><br />

<strong>Island</strong> as depauperate, schlerophyllous grassy heathlands (Rippey et al. 2003), a great<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trast from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> descripti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> early explorers.<br />

In an effort to repair <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitats <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> a management plan, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Woodland<br />

Restorati<strong>on</strong> Program, has been implemented. In <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> past decade <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> program has planted<br />

over 242,000 trees in fenced plantati<strong>on</strong>s (<strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority 2009), with an aim to<br />

return <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> woodlands <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island to c<strong>on</strong>nect remnant woodland habitats and return<br />

<strong>Rottnest</strong> to reflect what was described by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first col<strong>on</strong>ial settlers. Such drastic changes to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> vegetati<strong>on</strong> over <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> last two hundred years have impacted heavily <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> terrestrial bird<br />

species that use <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se habitats, leading to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> decline or local extincti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> several habitat<br />

sensitive species. O<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r species have resp<strong>on</strong>ded positively by increasing in both distributi<strong>on</strong><br />

and abundance. The change in status <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds <strong>on</strong> <strong>Rottnest</strong> and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir current<br />

distributi<strong>on</strong> is examined below.<br />

14

Figure 2.3: Major vegetati<strong>on</strong> associati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> as <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2010. Revegetati<strong>on</strong> plantati<strong>on</strong>s are outlined in red. GIS Imaging source used under WALIS Licence for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

n<strong>on</strong>-commercial use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> land informati<strong>on</strong> provided by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> WA, courtesy <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> Authority 2011.<br />

15

2.2 Methods<br />

2.2.1 Literature review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> avifauna<br />

The Western <str<strong>on</strong>g>Australian</str<strong>on</strong>g> Museum does not hold a suitable series <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> specimens or<br />

observati<strong>on</strong>al data to establish a timeline <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> change <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> islands avifauna. Of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 216 bird<br />

specimens lodged for <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, 210 were collected prior to 1910. Single specimens<br />

were lodged in 1990 and 1970, with two exotic House Crows Corvus splendens collected in<br />

2006. Several recent specimens were collected as part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this project. The majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

informati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> avifauna <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong> has been collated from field notebooks and<br />

observati<strong>on</strong>al records, and has been well documented since <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> declarati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> island as<br />

a recreati<strong>on</strong>al reserve. The first annotated list published was by Laws<strong>on</strong> (1904), with fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r<br />

lists by Alexander (1921), Glauert (1929) and Serventy (1938). Significant work was<br />

published by Storr (1965) and extensive l<strong>on</strong>g-term m<strong>on</strong>itoring has been published by<br />

Saunders and de Rebeira (1985 – 2009). Most recently, Birds Australia WA group has<br />

published <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir annual surveys <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> bush birds from 2000 - 2009 (Ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r 2009).<br />

I c<strong>on</strong>ducted a review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> previously published field studies <strong>on</strong> bush birds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Rottnest</strong> <strong>Island</strong>. I<br />

combined <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> species lists and <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> status <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each species from each author to illustrate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

change in species status over time. The summary was tabulated and compared to my own<br />

observati<strong>on</strong>al data to give <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> current status <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> each species.<br />

2.2.2 Study area and field observati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Six sites were selected at varying distances from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> central Thomps<strong>on</strong> Bay settlement<br />

(shopping district), with two sites each to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> north, south and west (central) (Figure 2.2a;<br />