They make a way. - Maryland Institute College of Art

They make a way. - Maryland Institute College of Art

They make a way. - Maryland Institute College of Art

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

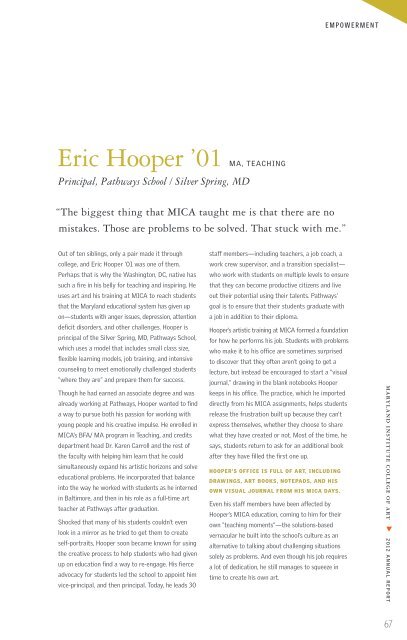

Eric Hooper ’01 MA, TEACHING<br />

Principal, Path<strong>way</strong>s School / Silver Spring, MD<br />

“The biggest thing that MICA taught me is that there are no<br />

mistakes. Those are problems to be solved. That stuck with me.”<br />

Out <strong>of</strong> ten siblings, only a pair made it through<br />

college, and Eric Hooper ’01 was one <strong>of</strong> them.<br />

Perhaps that is why the Washington, DC, native has<br />

such a fire in his belly for teaching and inspiring. He<br />

uses art and his training at MICA to reach students<br />

that the <strong>Maryland</strong> educational system has given up<br />

on—students with anger issues, depression, attention<br />

deficit disorders, and other challenges. Hooper is<br />

principal <strong>of</strong> the Silver Spring, MD, Path<strong>way</strong>s School,<br />

which uses a model that includes small class size,<br />

flexible learning models, job training, and intensive<br />

counseling to meet emotionally challenged students<br />

“where they are” and prepare them for success.<br />

Though he had earned an associate degree and was<br />

already working at Path<strong>way</strong>s, Hooper wanted to find<br />

a <strong>way</strong> to pursue both his passion for working with<br />

young people and his creative impulse. He enrolled in<br />

MICA’s BFA/ MA program in Teaching, and credits<br />

department head Dr. Karen Carroll and the rest <strong>of</strong><br />

the faculty with helping him learn that he could<br />

simultaneously expand his artistic horizons and solve<br />

educational problems. He incorporated that balance<br />

into the <strong>way</strong> he worked with students as he interned<br />

in Baltimore, and then in his role as a full-time art<br />

teacher at Path<strong>way</strong>s after graduation.<br />

Shocked that many <strong>of</strong> his students couldn’t even<br />

look in a mirror as he tried to get them to create<br />

self-portraits, Hooper soon became known for using<br />

the creative process to help students who had given<br />

up on education find a <strong>way</strong> to re-engage. His fierce<br />

advocacy for students led the school to appoint him<br />

vice-principal, and then principal. Today, he leads 30<br />

staff members—including teachers, a job coach, a<br />

work crew supervisor, and a transition specialist—<br />

who work with students on multiple levels to ensure<br />

that they can become productive citizens and live<br />

out their potential using their talents. Path<strong>way</strong>s’<br />

goal is to ensure that their students graduate with<br />

a job in addition to their diploma.<br />

Hooper’s artistic training at MICA formed a foundation<br />

for how he performs his job. Students with problems<br />

who <strong>make</strong> it to his <strong>of</strong>fice are sometimes surprised<br />

to discover that they <strong>of</strong>ten aren’t going to get a<br />

lecture, but instead be encouraged to start a “visual<br />

journal,” drawing in the blank notebooks Hooper<br />

keeps in his <strong>of</strong>fice. The practice, which he imported<br />

directly from his MICA assignments, helps students<br />

release the frustration built up because they can’t<br />

express themselves, whether they choose to share<br />

what they have created or not. Most <strong>of</strong> the time, he<br />

says, students return to ask for an additional book<br />

after they have filled the first one up.<br />

HOOPER’S OFFICE IS FULL OF ART, INCLUDING<br />

DRAWINGS, ART BOOKS, NOTEPADS, AND HIS<br />

OWN VISUAL JOURNAL FROM HIS MICA DAYS.<br />

Even his staff members have been affected by<br />

Hooper’s MICA education, coming to him for their<br />

own “teaching moments”—the solutions-based<br />

vernacular he built into the school’s culture as an<br />

alternative to talking about challenging situations<br />

solely as problems. And even though his job requires<br />

a lot <strong>of</strong> dedication, he still manages to squeeze in<br />

time to create his own art.<br />

EMPOWERMENT<br />

MARYLAND INSTITUTE COLLEGE OF ART 2012 ANNUAL REPORT<br />

67