Educating out of Poverty? A Synthesis Report on Ghana, India ... - DfID

Educating out of Poverty? A Synthesis Report on Ghana, India ... - DfID

Educating out of Poverty? A Synthesis Report on Ghana, India ... - DfID

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

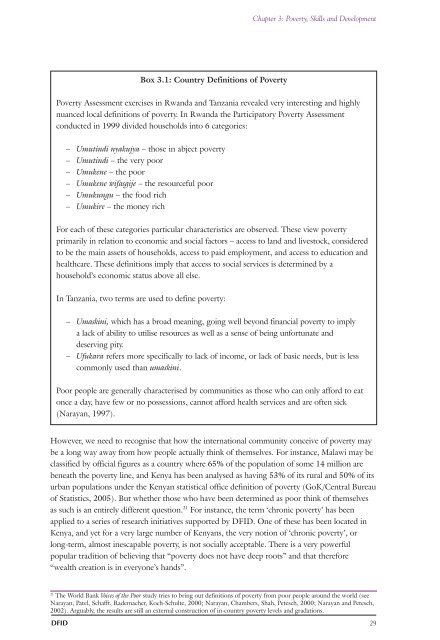

Box 3.1: Country Definiti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Chapter 3: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Skills and Development<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> Assessment exercises in Rwanda and Tanzania revealed very interesting and highly<br />

nuanced local definiti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty. In Rwanda the Participatory <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> Assessment<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted in 1999 divided households into 6 categories:<br />

– Umutindi nyakujya – those in abject poverty<br />

– Umutindi – the very poor<br />

– Umukene – the poor<br />

– Umukene wifasgije – the resourceful poor<br />

– Umukungu – the food rich<br />

– Umukire – the m<strong>on</strong>ey rich<br />

For each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these categories particular characteristics are observed. These view poverty<br />

primarily in relati<strong>on</strong> to ec<strong>on</strong>omic and social factors – access to land and livestock, c<strong>on</strong>sidered<br />

to be the main assets <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> households, access to paid employment, and access to educati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

healthcare. These definiti<strong>on</strong>s imply that access to social services is determined by a<br />

household’s ec<strong>on</strong>omic status above all else.<br />

In Tanzania, two terms are used to define poverty:<br />

– Umaskini, which has a broad meaning, going well bey<strong>on</strong>d financial poverty to imply<br />

a lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ability to utilise resources as well as a sense <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> being unfortunate and<br />

deserving pity.<br />

– Ufukara refers more specifically to lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> income, or lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> basic needs, but is less<br />

comm<strong>on</strong>ly used than umaskini.<br />

Poor people are generally characterised by communities as those who can <strong>on</strong>ly afford to eat<br />

<strong>on</strong>ce a day, have few or no possessi<strong>on</strong>s, cannot afford health services and are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten sick<br />

(Narayan, 1997).<br />

However, we need to recognise that how the internati<strong>on</strong>al community c<strong>on</strong>ceive <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty may<br />

be a l<strong>on</strong>g way away from how people actually think <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> themselves. For instance, Malawi may be<br />

classified by <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ficial figures as a country where 65% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the populati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> some 14 milli<strong>on</strong> are<br />

beneath the poverty line, and Kenya has been analysed as having 53% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its rural and 50% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its<br />

urban populati<strong>on</strong>s under the Kenyan statistical <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fice definiti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty (GoK/Central Bureau<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Statistics, 2005). But whether those who have been determined as poor think <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> themselves<br />

as such is an entirely different questi<strong>on</strong>. 21 For instance, the term ‘chr<strong>on</strong>ic poverty’ has been<br />

applied to a series <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> research initiatives supported by DFID. One <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these has been located in<br />

Kenya, and yet for a very large number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenyans, the very noti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ‘chr<strong>on</strong>ic poverty’, or<br />

l<strong>on</strong>g-term, almost inescapable poverty, is not socially acceptable. There is a very powerful<br />

popular traditi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> believing that “poverty does not have deep roots” and that therefore<br />

“wealth creati<strong>on</strong> is in every<strong>on</strong>e’s hands”.<br />

21 The World Bank Voices <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Poor study tries to bring <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> definiti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty from poor people around the world (see<br />

Narayan, Patel, Schafft, Rademacher, Koch-Schulte, 2000; Narayan, Chambers, Shah, Petesch, 2000; Narayan and Petesch,<br />

2002). Arguably, the results are still an external c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> in-country poverty levels and gradati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

DFID 29