Educating out of Poverty? A Synthesis Report on Ghana, India ... - DfID

Educating out of Poverty? A Synthesis Report on Ghana, India ... - DfID

Educating out of Poverty? A Synthesis Report on Ghana, India ... - DfID

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Researching the Issues<br />

2007<br />

70<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>?<br />

A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Ghana</strong>,<br />

<strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania<br />

and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

by Robert Palmer, Ruth Wedgwood and Rachel Hayman<br />

with Kenneth King and Neil Thin

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>?<br />

A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya,<br />

Rwanda, Tanzania and<br />

S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

by<br />

Robert Palmer, Ruth Wedgwood and Rachel Hayman<br />

with Kenneth King and Neil Thin<br />

2007<br />

Centre <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> African Studies, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Edinburgh

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

Educati<strong>on</strong>al Papers<br />

Department for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development: Educati<strong>on</strong>al Papers<br />

This is <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a series <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong> Papers issued by the Central Research Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

Department For Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development. Each paper represents a study or piece <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

commissi<strong>on</strong>ed research <strong>on</strong> some aspect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong> and training in developing countries. Most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the studies were undertaken in order to provide informed judgements from which policy decisi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

could be drawn, but in each case it has become apparent that the material produced would be <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

interest to a wider audience, particularly those whose work focuses <strong>on</strong> developing countries.<br />

Each paper is numbered serially. Further copies can be obtained through DFID Publicati<strong>on</strong>s –<br />

subject to availability. A full list <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> previous Educati<strong>on</strong> books and papers can be found <strong>on</strong> the<br />

following pages, al<strong>on</strong>g with informati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> how to order copies.<br />

Although these papers are issued by DFID, the views expressed in them are entirely those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

authors and do not necessarily represent DFID’s own policies or views. Any discussi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent should therefore be addressed to the authors and not to DFID.<br />

Address for Corresp<strong>on</strong>dence<br />

Centre <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> African Studies,<br />

University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Edinburgh,<br />

21 George Square,<br />

Edinburgh<br />

EH8 9LD<br />

UK<br />

Tel: 0131 650 3878<br />

Fax: 0131 650 6535<br />

Email: African.Studies@ed.ac.uk<br />

Website: www.cas.ed.ac.uk<br />

© Centre <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> African Studies, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Edinburgh<br />

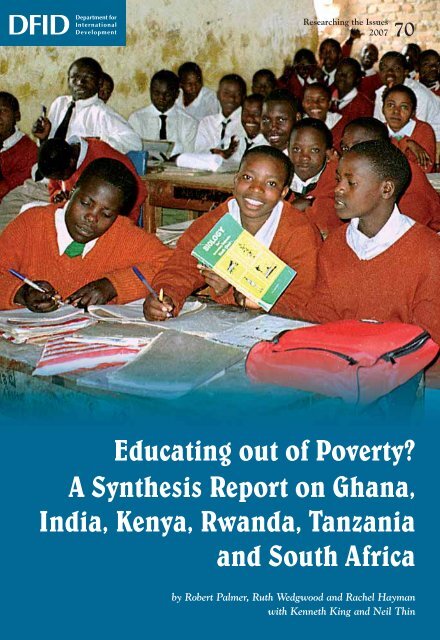

Fr<strong>on</strong>t cover photograph: Form II Class at Udzungwa Sec<strong>on</strong>dary School,<br />

Tanzania, © Ruth Wedgwood<br />

DFID

No. 1 SCHOOL EFFECTIVENESS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES:<br />

A SUMMARY OF THE RESEARCH EVIDENCE.<br />

D. Pennycuick (1993) ISBN: 0 90250 061 9<br />

No. 2 EDUCATIONAL COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS.<br />

J. Hough (1993) ISBN: 0 90250 062 7<br />

No. 3 REDUCING THE COST OF TECHNICAL AND VOCATIONAL<br />

EDUCATION.<br />

L. Gray, M. Fletcher, P. Foster, M. King, A. M. Warrender (1993) ISBN: 0 90250 063 5<br />

No. 4 REPORT ON READING IN ENGLISH IN PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN MALAWI.<br />

E. Williams (1993) Out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Print – Available <strong>on</strong> CD-Rom and DFID website<br />

No. 5 REPORT ON READING IN ENGLISH IN PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN ZAMBIA.<br />

E. Williams (1993) Out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Print – Available <strong>on</strong> CD-Rom and DFID website<br />

See also No. 24, which updates and synthesises Nos 4 and 5.<br />

No. 6 EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT: THE ISSUES AND THE EVIDENCE.<br />

K. Lewin (1993) ISBN: 0 90250 066 X<br />

No. 7 PLANNING AND FINANCING SUSTAINABLE EDUCATION SYSTEMS<br />

IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA.<br />

P. Penrose (1993) ISBN: 0 90250 067 8<br />

No. 8 Not allocated<br />

No. 9 FACTORS AFFECTING FEMALE PARTICIPATION IN EDUCATION IN<br />

SEVEN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES.<br />

C. Brock, N. Cammish (1991) (revised 1997) ISBN: 1 86192 065 2<br />

No. 10 USING LITERACY: A NEW APPROACH TO POST-LITERACY METHODS.<br />

A. Rogers (1994) Out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Print – Available <strong>on</strong> CD-ROM and DFID website.<br />

Updated and reissued as No 29.<br />

No. 11 EDUCATION AND TRAINING FOR THE INFORMAL SECTOR.<br />

K. King, S. McGrath, F. Leach, R. Carr-Hill (1995) ISBN: 1 86192 090 3<br />

No. 12 MULTI-GRADE TEACHING: A REVIEW OF RESEARCH AND PRACTICE.<br />

A. Little (1995) ISBN: 0 90250 058 9<br />

No. 13 DISTANCE EDUCATION IN ENGINEERING FOR DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES.<br />

T. Bilham, R. Gilmour (1995) Out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Print – Available <strong>on</strong> CD-ROM and DFID website.<br />

No. 14 HEALTH & HIV/AIDS EDUCATION IN PRIMARY & SECONDARY<br />

SCHOOLS IN AFRICA & ASIA.<br />

E. Barnett, K. de K<strong>on</strong>ing, V. Francis (1995) ISBN: 0 90250 069 4<br />

No. 15 LABOUR MARKET SIGNALS & INDICATORS.<br />

L. Gray, A. M. Warrender, P. Davies, G. Hurley, C. Mant<strong>on</strong> (1996)<br />

Out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Print – Available <strong>on</strong> CD-ROM and DFID website.<br />

Educati<strong>on</strong>al Papers<br />

No. 16 IN-SERVICE SUPPORT FOR A TECHNOLOGICAL APPROACH TO<br />

SCIENCE EDUCATION.<br />

F. Lubben, R. Campbell, B. Dlamini (1995) ISBN: 0 90250 071 6<br />

DFID

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

No. 17 ACTION RESEARCH REPORT ON “REFLECT”.<br />

D. Archer, S. Cottingham (1996) ISBN: 0 90250 072 4<br />

No. 18 THE EDUCATION AND TRAINING OF ARTISANS FOR THE<br />

INFORMAL SECTOR IN TANZANIA.<br />

D. Kent, P. Mushi (1995) ISBN: 0 90250 074 0<br />

No. 19 GENDER, EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT – A PARTIALLY<br />

ANNOTATED AND SELECTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY.<br />

C. Brock, N. Cammish (1997)<br />

Out <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Print – Available <strong>on</strong> CD-ROM and DFID website.<br />

No. 20 CONTEXTUALISING TEACHING AND LEARNING IN RURAL<br />

PRIMARY SCHOOLS: USING AGRICULTURAL EXPERIENCE.<br />

P. Taylor, A. Mulhall (Vols 1 & 2) (1997)<br />

Vol 1 ISBN: 1 861920 45 8 Vol 2 ISBN: 1 86192 050 4<br />

No. 21 GENDER AND SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN THE CARIBBEAN.<br />

P. Kutnick, V. Jules, A. Layne (1997) ISBN: 1 86192 080 6<br />

No. 22 SCHOOL-BASED UNDERSTANDING OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN<br />

FOUR COUNTRIES: A COMMONWEALTH STUDY.<br />

R. Bourne, J. Gundara, A. Dev, N. Ratsoma, M. Rukanda, A. Smith, U. Birthistle<br />

(1997) ISBN: 1 86192 095 4<br />

No. 23 GIRLS AND BASIC EDUCATION: A CULTURAL ENQUIRY.<br />

D. Stephens (1998) ISBN: 1 86192 036 9<br />

No. 24 INVESTIGATING BILINGUAL LITERACY: EVIDENCE FROM MALAWI<br />

AND ZAMBIA.<br />

E. Williams (1998) ISBN: 1 86192 041 5<br />

No. 25 PROMOTING GIRLS’ EDUCATION IN AFRICA.<br />

N. Swains<strong>on</strong>, S. Bendera, R. Gord<strong>on</strong>, E. Kadzamira (1998) ISBN: 1 86192 046 6<br />

No. 26 GETTING BOOKS TO SCHOOL PUPILS IN AFRICA.<br />

D. Rosenberg, W. Amaral, C. Odini, T. Radebe, A. Sidibé (1998) ISBN: 1 86192 051 2<br />

No. 27 COST SHARING IN EDUCATION.<br />

P. Penrose (1998) ISBN: 1 86192 056 3<br />

No. 28 VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING IN TANZANIA AND<br />

ZIMBABWE IN THE CONTEXT OF ECONOMIC REFORM.<br />

P. Bennell (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 061 X<br />

No. 29 RE-DEFINING POST-LITERACY IN A CHANGING WORLD.<br />

A. Rogers, B. Maddox, J. Millican, K. Newell J<strong>on</strong>es, U. Papen, A. Robins<strong>on</strong>-Pant<br />

(1999) ISBN: 1 86192 069 5<br />

No. 30 IN SERVICE FOR TEACHER DEVELOPMENT IN SUB-SAHARAN<br />

AFRICA.<br />

M. M<strong>on</strong>k (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 074 1<br />

No. 31 LOCALLY GENERATED PRINTED MATERIALS IN AGRICULTURE:<br />

EXPERIENCE FROM UGANDA & GHANA.<br />

I. Carter (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 079 2<br />

DFID

No. 32 SECTOR WIDE APPROACHES TO EDUCATION.<br />

M. Ratcliffe, M. Macrae (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 131 4<br />

No. 33 DISTANCE EDUCATION PRACTICE: TRAINING & REWARDING<br />

AUTHORS.<br />

H. Perrat<strong>on</strong>, C. Creed (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 136 5<br />

No. 34 THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TEACHER RESOURCE CENTRE STRATEGY.<br />

Ed. G. Knamiller (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 141 1<br />

No. 35 EVALUATING IMPACT.<br />

Ed. V. McKay, C. Treffgarne (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 191 8<br />

No. 36 AFRICAN JOURNALS.<br />

A. Alemna, V. Chifwepa, D. Rosenberg (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 157 8<br />

No. 37 MONITORING THE PERFORMANCE OF EDUCATIONAL<br />

PROGRAMMES IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES.<br />

R. Carr-Hill, M. Hopkins, A. Riddell, J. Lintott (1999) ISBN: 1 86192 224 8<br />

No. 38 TOWARDS RESPONSIVE SCHOOLS – SUPPORTING BETTER<br />

SCHOOLING FOR DISADVANTAGED CHILDREN.<br />

(case studies from Save the Children).<br />

M. Molteno, K. Ogadhoh, E. Cain, B. Crumpt<strong>on</strong> (2000)<br />

No. 39 PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION OF THE ABUSE OF GIRLS IN<br />

ZIMBABWEAN JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOLS.<br />

F. Leach, P. Machankanja with J. Mandoga (2000) ISBN: 1 86192 279 5<br />

No. 40 THE IMPACT OF TRAINING ON WOMEN’S MICRO-ENTERPRISE<br />

DEVELOPMENT.<br />

F. Leach, S. Abdulla, H. Applet<strong>on</strong>, J. el-Bushra, N. Cardenas, K. Kebede, V. Lewis,<br />

S. Sitaram (2000) ISBN: 1 86192 284 1<br />

No. 41 THE QUALITY OF LEARNING AND TEACHING IN DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES: ASSESSING LITERACY AND NUMERACY IN MALAWI<br />

AND SRI LANKA.<br />

D. Johns<strong>on</strong>, J. Hayter, P. Broadfoot (2000) ISBN: 1 86192 313 9<br />

No. 42 LEARNING TO COMPETE: EDUCATION, TRAINING & ENTERPRISE<br />

IN GHANA, KENYA & SOUTH AFRICA.<br />

D. Afenyadu, K. King, S. McGrath, H. Oketch, C. Rogers<strong>on</strong>, K. Visser (2001)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 314 7<br />

No. 43 COMPUTERS IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN DEVELOPING<br />

COUNTRIES: COSTS AND OTHER ISSUES.<br />

A. Cawthera (2001) ISBN: 1 86192 418 6<br />

Educati<strong>on</strong>al Papers<br />

No. 44 THE IMPACT OF HIV/AIDS ON THE UNIVERSITY OF BOTSWANA:<br />

DEVELOPING A COMPREHENSIVE STRATEGIC RESPONSE.<br />

B. Chilisa, P. Bennell, K. Hyde (2001) ISBN: 1 86192 467 4<br />

No. 45 THE IMPACT OF HIV/AIDS ON PRIMARY AND SECONDARY<br />

EDUCATION IN BOTSWANA: DEVELOPING A COMPREHENSIVE<br />

STRATEGIC RESPONSE.<br />

P. Bennell, B. Chilisa, K. Hyde, A. Makgothi, E. Molobe, L. Mpotokwane (2001)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 468 2<br />

DFID

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

No. 46 EDUCATION FOR ALL: POLICY AND PLANNING – LESSONS FROM<br />

SRI LANKA.<br />

A. Little (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 552 0<br />

No. 47 REACHING THE POOR – THE 'COSTS' OF SENDING CHILDREN TO<br />

SCHOOL.<br />

S. Boyle, A. Brock, J. Mace, M. Sibb<strong>on</strong>s (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 361 9<br />

No. 48 CHILD LABOUR AND ITS IMPACT ON CHILDREN’S ACCESS TO AND<br />

PARTICIPATION IN PRIMARY EDUCATION – A CASE STUDY FROM<br />

TANZANIA.<br />

H. A. Dachi and R. M. Garrett (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 536 0<br />

No. 49a MULTI – SITE TEACHER EDUCATION RESEARCH PROJECT<br />

(MUSTER)<br />

RESEARCHING TEACHER EDUCATION – NEW PERSPECTIVES ON<br />

PRACTICE, PERFORMANCE AND POLICY (<str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g>).<br />

K. M. Lewin and J. S. Stuart (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 545 X<br />

No. 49b TEACHER TRAINING IN GHANA – DOES IT COUNT?<br />

K. Akyeamp<strong>on</strong>g (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 546 8<br />

No. 49c INITIAL PRIMARY TEACHER EDUCATION IN LESOTHO.<br />

K. Pulane Lefoka with E. Molapi Sebatane (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 547 64<br />

No. 49d PRIMARY TEACHER EDUCATION IN MALAWI: INSIGHTS INTO<br />

PRACTICE AND POLICY.<br />

D. Kunje with K. Lewin and J. Stuart (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 548 4<br />

No. 49e AN ANALYSIS OF PRIMARY TEACHER EDUCATION IN TRINIDAD<br />

AND TOBAGO.<br />

J. George, L. Quamina-Alyejina (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 549 2<br />

No. 50 USING ICT TO INCREASE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF COMMUNITY-<br />

BASED, NON-FORMAL EDUCATION FOR RURAL PEOPLE IN SUB-<br />

SAHARAN AFRICA.<br />

The CERP project (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 568 9<br />

No. 51 GLOBALISATION AND SKILLS FOR DEVELOPMENT IN RWANDA<br />

AND TANZANIA.<br />

L. Tikly, J. Lowe, M. Crossley, H. Dachi, R. Garrett and B. Mukabaranga (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 569 7<br />

No. 52 UNDERSTANDINGS OF EDUCATION IN ANAFRICAN VILLAGE:<br />

THE IMPACT OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION<br />

TECHNOLOGIES.<br />

J. Pryor and J. G. Ampiah (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 570 0<br />

No. 53 LITERACY, GENDER AND SOCIAL AGENCY: ADVENTURES IN<br />

EMPOWERMENT.<br />

M. Fiedrich and A. Jellema (2003) ISBN: 1 86192 5719<br />

No. 54 AN INVESTIGATIVE STUDY OF THE ABUSE OF GIRLS IN<br />

AFRICAN SCHOOLS.<br />

F. Leach, V. Fiscian, E. Kadzamira, E. Lemani and P. Machakanja (2003)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 5751<br />

DFID

No. 55 DISTRICT INSTITUTES OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING:<br />

A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN THREE INDIAN STATES.<br />

C. Dyer, A. Choksi, V. Awasty, U. Iyer, R. Moyade, N. Nigam, N. Purohit,<br />

S. Shah and S. Sheth (2004) ISBN: 1 86192 606 5<br />

No. 56 GENDERED SCHOOL EXPERIENCES: THE IMPACT ON RETENTION<br />

AND ACHIEVEMENT IN BOTSWANA AND GHANA.<br />

M. Dunne, F. Leach, B. Chilisa, T. Maundeni, R. Tabulawa, N. Kutor, L. Dzama<br />

Forde, and A. Asamoah (2005) ISBN: 1 86192 5751<br />

No. 57 FINANCING PRIMARY EDUCATION FOR ALL: PUBLIC<br />

EXPENDITURE AND EDUCATION OUTCOMES IN AFRICA.<br />

S. Al-Samarrai (2005) ISBN: 1 86192 6391<br />

No. 58 DEEP IMPACT: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE USE OF INFORMATION<br />

AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY FOR TEACHER EDUCATION<br />

IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH.<br />

J. Leach with A. Ahmed, S. Makalima and T. Power (2005) ISBN: 1 86192 7126<br />

No. 59 NON-GOVERNMENT SECONDARY SCHOOLING IN SUB-SAHARAN<br />

AFRICA. EXPLORING THE EVIDENCE IN SOUTH AFRICA AND<br />

MALAWI.<br />

K. M. Lewin and Y. Sayed (2005) ISBN: 1 86192 7436<br />

No. 60 EDUCATION REFORM IN UGANDA – 1997 TO 2004. REFLECTIONS<br />

ON POLICY, PARTNERSHIP, STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION.<br />

M. Ward, A. Penny and T. Read (2006) ISBN: 1 86192 8165<br />

No. 61 THE ROLE OF OPEN, DISTANCE AND FLEXIBLE LEARNING (ODFL)<br />

IN HIV/AIDS PREVENTION AND MITIGATION FOR AFFECTED<br />

YOUTH IN SOUTH AFRICA AND MOZAMBIQUE. FINAL REPORT.<br />

P. Pridmore and C. Yates with K. Kuhn and H. Xerinda (2006) ISBN: 1 86192 7959<br />

No. 62 USING DISTANCE EDUCATION FOR SKILLS DEVELOPMENT.<br />

R. Raza and T. Allsop (2006) ISBN: 1 86192 8173<br />

No. 63 FIELD-BASED MODELS OF PRIMARY TEACHER TRAINING.<br />

CASE STUDIES OF STUDENT SUPPORT SYSTEMS FROM<br />

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA.<br />

E. Matts<strong>on</strong> (2006) ISBN: 1 86192 8181<br />

Educati<strong>on</strong>al Papers<br />

No. 64 TEACHER EDUCATION AT A DISTANCE: IMPACT ON DEVELOPMENT<br />

IN THE COMMUNITY.<br />

F. Binns and T. Wrights<strong>on</strong> (2006) ISBN: 1 86192 819X<br />

No. 65 GENDER EQUITY IN COMMONWEALTH HIGHER EDUCATION:<br />

AN EXAMINATION OF SUSTAINABLE INTERVENTIONS IN SELECTED<br />

COMMONWEALTH UNIVERSITIES.<br />

L.Morley with C. Gunawardena, J. Kwesiga, A. Lihamba, A. Odejide, L. Shacklet<strong>on</strong><br />

and A. Sorhaindo (2006) ISBN: 1 86192 7614<br />

No. 66 TEACHER MOBILITY, ‘BRAIN DRAIN’, LABOUR MARKETS AND<br />

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES IN THE COMMONWEALTH.<br />

W. John Morgan, A. Sives and S. Applet<strong>on</strong> (2006) ISBN: 1 86192 7622<br />

DFID

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

No. 67 ALTERNATIVE BASIC EDUCATION IN AFRICAN COUNTRIES<br />

EMERGING FROM CONFLICT; ISSUES OF POLICY, CO-ORDINATION<br />

AND ACCESS.<br />

C. Dennis and A. Fentiman (2007)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 869 6<br />

No. 68 GLOBALISATION, EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT: IDEAS,<br />

ACTORS AND DYNAMICS<br />

S. Roberts<strong>on</strong>, M. Novelli, R. Dale, L. Tikly, H. Dachi and N. Alph<strong>on</strong>ce (2007)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 870 X<br />

No. 69 EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT IN A GLOBAL ERA: STRATEGIES<br />

FOR ‘SUCCESSFUL GLOBALISATION’<br />

A. Green, A. W. Little, S. G. Kamat, M. O. Oketch and E. Vickers (2007)<br />

ISBN: 1 86192 871 8<br />

NOW AVAILABLE – CD-ROM c<strong>on</strong>taining full texts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Papers 1-42.<br />

Other DFID Educati<strong>on</strong>al Studies Also Available:<br />

REDRESSING GENDER INEQUALITIES IN EDUCATION. N. Swains<strong>on</strong> (1995)<br />

FACTORS AFFECTING GIRLS’ ACCESS TO SCHOOLING IN NIGER. S. Wynd<br />

(1995)<br />

EDUCATION FOR RECONSTRUCTION. D. Phillips, N. Arnhold, J. Bekker,<br />

N. Kersh, E. McLeish (1996)<br />

AFRICAN JOURNAL DISTRIBUTION PROGRAMME: EVALUATION OF 1994<br />

PILOT PROJECT. D. Rosenberg (1996)<br />

TEACHER JOB SATISFACTION IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES. R. Garrett (1999)<br />

A MODEL OF BEST PRACTICE AT LORETO DAY SCHOOL, SEALDAH,<br />

CALCUTTA. T. Jessop (1998)<br />

LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES FOR ALL. DFID Policy Paper (1999)<br />

THE CHALLENGE OF UNIVERSAL PRIMARY EDUCATION.<br />

DFID Target Strategy Paper (2001)<br />

CHILDREN OUT OF SCHOOL. DFID Issues Paper (2001)<br />

All publicati<strong>on</strong>s are available free <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> charge from DFID Publicati<strong>on</strong>s, and can be ordered by<br />

email to dfidpubs@ecgroup.uk.com or by writing to EC Group, Europa Park, Magnet Road,<br />

Grays, Essex, RN20 4DN. Most publicati<strong>on</strong>s can also be downloaded or ordered from the<br />

R4D Research Portal and Publicati<strong>on</strong>s secti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the DFID website (www.dfid.gov.uk).<br />

DFID

The Research Team<br />

For full details <strong>on</strong> the country and overview studies please see the appendix.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> report<br />

Robert Palmer<br />

Ruth Wedgwood<br />

Rachel Hayman<br />

Kenneth King<br />

Neil Thin<br />

Country studies<br />

Robert Palmer (<strong>Ghana</strong>)<br />

Jandhyala Tilak (<strong>India</strong>)<br />

Kenneth King (Kenya)<br />

Rachel Hayman (Rwanda)<br />

Ruth Wedgwood (Tanzania)<br />

Salim Akoojee and Sim<strong>on</strong> McGrath (S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa)<br />

Overview studies<br />

Kenneth King<br />

Robert Palmer<br />

Jandhyala Tilak<br />

Coordinati<strong>on</strong><br />

Kenneth King<br />

Robert Palmer<br />

Neil Thin<br />

The Research Team<br />

DFID i

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

Preface and Acknowledgements<br />

This Research M<strong>on</strong>ograph is <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the final <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> collaborative research<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted with the support <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Department for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development (DFID) over the<br />

period from April 2004 to May 2006. A str<strong>on</strong>g c<strong>on</strong>cern over the two year period has been with<br />

the disseminati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our findings into different research and policy c<strong>on</strong>stituencies, both in the<br />

North and the S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h. The researchers were anxious to ensure that this activity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> engagement<br />

with end-users took place through<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> the whole period, and was not something that <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

happened <strong>on</strong>ce the project was finished.<br />

Thus, a first <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>come <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research was the organisati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a special panel <strong>on</strong> our research<br />

theme in the Annual C<strong>on</strong>ference <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Development Studies Associati<strong>on</strong>, just seven m<strong>on</strong>ths after<br />

the work had started. This panel provided a first translati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our initial research into a policy<br />

audience, since the other members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the panel included Desm<strong>on</strong>d Bermingham <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> DFID, and<br />

Kevin Watkins, Editor <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Human Development <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g>. This first paper was published, in 2005,<br />

in a special issue <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development, supported by DFID, appropriately<br />

entitled ‘Bridging Research and Policy’, and also appeared in a book <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> similar title edited by<br />

Court and Maxwell (2006).<br />

The six country studies were all completed in near to final draft by March 2005. It was possible<br />

for them all to be available as background papers, by the time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Centre <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> African Studies’<br />

(CAS) Internati<strong>on</strong>al C<strong>on</strong>ference in Edinburgh in April 2005. This CAS C<strong>on</strong>ference was itself<br />

deliberately oriented around the key themes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the DFID project, and hence the published<br />

volume from the CAS c<strong>on</strong>ference, Revisiting Educati<strong>on</strong>, Training and Work in Africa (CAS,<br />

October 2005) set the DFID research <strong>on</strong> five African countries within a larger African c<strong>on</strong>text.<br />

Immediately after the CAS c<strong>on</strong>ference, there was an interacti<strong>on</strong> with high level policy makers<br />

from <strong>Ghana</strong>, Kenya, Tanzania and <strong>India</strong>, in order to get early feedback <strong>on</strong> the research from these<br />

senior members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the policy community.<br />

Over the summer <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2005, the lengthy, individual country studies were versi<strong>on</strong>ed into academic<br />

papers for what was a crucial panel <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the UKFIET’s Oxford Internati<strong>on</strong>al C<strong>on</strong>ference <strong>on</strong><br />

Educati<strong>on</strong> and Development that September. This panel was entitled ‘<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> and Training <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>’, and thus was organised in large part around our DFID research theme. It attracted<br />

much interest from researchers and policy makers, and the panel eventually had some 20 papers<br />

addressing similar issues to our own. By good fortune, all the DFID country studies that were<br />

presented in Oxford were also accepted by the Internati<strong>on</strong>al Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong>al Development;<br />

which means that during 2007, the DFID country studies will be available in <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most<br />

widely circulated comparative educati<strong>on</strong> journals, worldwide. 1<br />

C<strong>on</strong>scious that most policy makers whether in agencies or in our six selected countries do not<br />

have the time to read lengthy country studies or academic papers, we versi<strong>on</strong>ed our country<br />

studies into short, sharp Policy Briefs. These are <strong>on</strong> our website<br />

(http://www.cas.ed.ac.uk/research/projects.html) al<strong>on</strong>g with the country studies and the academic<br />

versi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the papers. But packages c<strong>on</strong>taining the Policy Briefs, the Executive Summaries <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our<br />

country studies and the country studies themselves have been sent to carefully selected policy<br />

makers in each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our research countries. There has been a very positive feedback from this<br />

process. The same package was also sent to the DFID advisors’ meeting in Nairobi in early 2006.<br />

ii DFID

It also proved possible for our DFID research to be fed into the main d<strong>on</strong>or agencies c<strong>on</strong>cerned<br />

with the relati<strong>on</strong>ship <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> skills and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>. Both in the Working Group for<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Cooperati<strong>on</strong> in Skills Development and in the European Training Foundati<strong>on</strong> in<br />

November and December <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2005 respectively, major presentati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> Skills and <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Reducti<strong>on</strong> were made at these agency meetings in Italy. While a little earlier in the year, the<br />

results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our DFID work were also presented to a meeting <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> USAID’s educati<strong>on</strong> advisors<br />

in Washingt<strong>on</strong>.<br />

The summaries <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> our six country studies al<strong>on</strong>g with many other articles <strong>on</strong> the Educati<strong>on</strong>-<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reducti<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ship have been a key element in the Aid Policy Bulletin, NORRAG<br />

NEWS NO. 37, which was published in May 2006. The theme <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this special issue was ‘<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A status report’. This Bulletin goes to over 1200 individuals in academia, NGOs<br />

and in policy circles around the world. No less than 40% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the readership is in the developing<br />

world. A further opportunity to present the results <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research was in the biennial c<strong>on</strong>ference<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the African Studies Associati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the UK in SOAS in September 2006.<br />

The present m<strong>on</strong>ograph, and the accompanying summary which goes into the id21 process,<br />

c<strong>on</strong>stitute the final <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>come <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this two year research. Here, our purpose has been to look across<br />

the six country c<strong>on</strong>texts and synthesise some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the comm<strong>on</strong> less<strong>on</strong>s learnt and policy challenges<br />

met in the research process.<br />

We would thank colleagues in DFID, and especially Desm<strong>on</strong>d Bermingham and David Levesque,<br />

for the interest they have shown in the research, and for their readiness to participate in the<br />

several different panels, c<strong>on</strong>ferences and feedback sessi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> the research as it went through<br />

these several stages. DFID, however, is not resp<strong>on</strong>sible for the views expressed here or in the<br />

many other <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>puts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research; these remain the resp<strong>on</strong>sibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research team.<br />

We would also want to acknowledge our colleagues in the six countries, whether in government,<br />

in NGOs, or in academia, who have given their time to discussing these research issues with us.<br />

We would also want to thank them for giving us the opportunity <strong>on</strong> a number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> occasi<strong>on</strong>s to<br />

feed back our findings to them.<br />

Finally, the Edinburgh team, which has taken resp<strong>on</strong>sibility for the synthesising <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this final<br />

report, would like to acknowledge the other members <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the team <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>side Edinburgh, who have<br />

been our research partners over these two years. These are Salim Akoojee (in Pretoria) and Sim<strong>on</strong><br />

McGrath (formerly Pretoria, now Nottingham) who are the authors <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa country<br />

study, and Jandhyala Tilak (in New Delhi) who has been resp<strong>on</strong>sible for the <strong>India</strong> country paper<br />

as well as a general review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the role <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> in poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> and<br />

development.<br />

Kenneth King,<br />

Principal Investigator,<br />

Centre <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> African Studies,<br />

Edinburgh University<br />

Preface and Acknowledgements<br />

1 See Internati<strong>on</strong>al Journal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong>al Development 27/4 (2007) Special issue: Bey<strong>on</strong>d Basic Educati<strong>on</strong> and towards an<br />

Expanded Vis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Educati<strong>on</strong> for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reducti<strong>on</strong> and Growth? (A full list <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the papers in IJED are in the Appendix <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

this report).<br />

DFID iii

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

iv DFID

C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

The Research Team i<br />

Preface and Acknowledgements ii<br />

C<strong>on</strong>tents v<br />

List <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tables, Figures and Boxes vi<br />

Acr<strong>on</strong>yms viii<br />

Executive Summary ix<br />

1. Introducti<strong>on</strong> 1<br />

1.1 Background 1<br />

1.2 Research questi<strong>on</strong>s 2<br />

1.3 What is ‘Basic Educati<strong>on</strong>’? 3<br />

1.4 Country studies 4<br />

1.5 Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the formal educati<strong>on</strong> systems <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the six countries 6<br />

1.6 Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the training systems <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the six countries 10<br />

1.7 Overview <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the report 11<br />

2. Linking Educati<strong>on</strong>, Skills and C<strong>on</strong>text 13<br />

2.1 A theoretical framework for investigating the linkages between educati<strong>on</strong>, 13<br />

training and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong><br />

2.2 The c<strong>on</strong>ceptual and methodological challenges <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> linking educati<strong>on</strong>, skills and 16<br />

poverty reducti<strong>on</strong><br />

2.3 The ‘farmer educati<strong>on</strong> fallacy in development planning’ and the importance 20<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>text<br />

2.4 Bey<strong>on</strong>d basic educati<strong>on</strong> 22<br />

2.5 Educati<strong>on</strong>, skills, poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>, growth and equity – some key issues 23<br />

3. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Skills and Development 27<br />

3.1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> and the poor in the nati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>texts 28<br />

3.2 Skills, poverty and ec<strong>on</strong>omic growth in nati<strong>on</strong>al policy 33<br />

3.3 External financing and educati<strong>on</strong> policy 39<br />

4. Research Evidence from the Six Countries 43<br />

4.1 Ec<strong>on</strong>omic returns to educati<strong>on</strong> 44<br />

4.2 Educati<strong>on</strong> and employment 49<br />

4.3 Educati<strong>on</strong> and enterprise 52<br />

4.4 Educati<strong>on</strong> and agriculture 53<br />

4.5 Other returns to educati<strong>on</strong> 54<br />

4.6 Internati<strong>on</strong>al and inter-state correlati<strong>on</strong>s: capturing the externalities 58<br />

4.7 Less<strong>on</strong>s from history 60<br />

4.8 Equality and post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> 62<br />

4.9 Skills training and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> 65<br />

5. Educati<strong>on</strong>, Training and Enabling Envir<strong>on</strong>ments 71<br />

5.1 The delivery c<strong>on</strong>text 73<br />

5.2 The transformative c<strong>on</strong>text: educati<strong>on</strong> as part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a wider multi-sectoral approach 78<br />

5.3 A disabling envir<strong>on</strong>ment for educati<strong>on</strong> and training? 85<br />

5.4 C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> a two-way relati<strong>on</strong>ship <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong> and training with their 89<br />

enabling envir<strong>on</strong>ments<br />

DFID v

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

6. C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s 91<br />

6.1 The importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>text in the educati<strong>on</strong>-poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ship 91<br />

6.2 The delivery c<strong>on</strong>text: ensuring positive <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes for basic educati<strong>on</strong> 96<br />

6.3 The transformative c<strong>on</strong>text: translating educati<strong>on</strong>, skills and knowledge 97<br />

development into poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> and growth<br />

6.4 Addressing equality 98<br />

6.5 Areas needing new empirical research 99<br />

Bibliography 103<br />

Appendix: List <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> papers from the project 123<br />

List <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tables, Figures and Boxes<br />

Tables<br />

Table 1.1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> incidence 5<br />

Table 1.2 Selected country indicators 5<br />

Table 1.3 Comparis<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the formal educati<strong>on</strong> systems in the six 7<br />

country case studies<br />

Table 1.4 Enrolment ratios at the primary, sec<strong>on</strong>dary and tertiary levels 7<br />

in selected countries in SSA and <strong>India</strong>, 2002/3<br />

Table 1.5 Private enrolment as a % <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> total enrolment 8<br />

Table 1.6 Primary educati<strong>on</strong>: survival (completi<strong>on</strong>) rates and transiti<strong>on</strong> 9<br />

to sec<strong>on</strong>dary educati<strong>on</strong> in selected countries in SSA and <strong>India</strong>,<br />

2001/2<br />

Table 1.7 Enrolment in sec<strong>on</strong>dary technical and vocati<strong>on</strong>al school as a 10<br />

percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> total sec<strong>on</strong>dary school enrolments in selected<br />

countries in SSA and S.Asia 2002/3<br />

Table 2.1 A typology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> analytical c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s for linking educati<strong>on</strong> 18<br />

and skills training to poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes<br />

Table 4.1 Internati<strong>on</strong>al averages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> return to educati<strong>on</strong> 44<br />

Table 4.2 Social rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> return reported in country studies 45<br />

Table 4.3 Private rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> return from country studies 45<br />

Table 4.4 Private returns to educati<strong>on</strong> by employment sector 46<br />

(informal / formal)<br />

Table 4.5 Correlati<strong>on</strong>s between educati<strong>on</strong> and poverty indicators 54<br />

in Rwanda<br />

Table 4.6 Fertility rates by residence and educati<strong>on</strong> level 57<br />

Table 4.7 Coefficient <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> correlati<strong>on</strong> between educati<strong>on</strong> and poverty 59<br />

Table 4.8 Regressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ln poverty ratio (1999-2000) <strong>on</strong> percentage 59<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> with sec<strong>on</strong>dary and higher educati<strong>on</strong> (1995-96)<br />

Table 4.9 Regressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ln infant mortality rate (2001) <strong>on</strong> percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 60<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> with sec<strong>on</strong>dary and higher educati<strong>on</strong> (1995-96)<br />

Table 4.10 Regressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ln life expectancy at birth (2001-06) <strong>on</strong> 60<br />

percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> with sec<strong>on</strong>dary and higher educati<strong>on</strong><br />

(1995-96)<br />

vi

Table 4.11 Activities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> apprentices after apprenticeship 69<br />

Table 5.1 Doing business in S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa, Kenya, <strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong> Tanzania 84<br />

and Rwanda<br />

Table 6.1 Fallacies associated with educati<strong>on</strong> and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> 92<br />

Figures<br />

Fig 6.1 Translating educati<strong>on</strong>, skills and knowledge development 95<br />

into poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> and growth<br />

Boxes<br />

Acr<strong>on</strong>yms and Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Box 3.1 Country definiti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty 29<br />

Box 3.2 Popular percepti<strong>on</strong>s ab<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong>, poverty and employment 31<br />

Box 3.3 Educati<strong>on</strong>, skills and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> in Tanzanian policy 35<br />

Box 3.4 Educati<strong>on</strong> sector strategies in Kenya and Rwanda 35<br />

Box 3.5 Prioritisati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong> and training in Rwanda 36<br />

Box 3.6 <strong>Ghana</strong>’s New Educati<strong>on</strong> Reform 38<br />

Box 4.1 The importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> traditi<strong>on</strong>al apprenticeship training in <strong>Ghana</strong> 68<br />

Box 5.1 Uncoordinated skills delivery in <strong>Ghana</strong> and the arrival <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> COTVET 77<br />

Box 5.2 Educati<strong>on</strong> and training <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes disabled by corrupti<strong>on</strong> in Kenya 81<br />

Box 5.3 The educati<strong>on</strong> and training policy envir<strong>on</strong>ment: making educati<strong>on</strong> 82<br />

more relevant to the world <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> work in <strong>Ghana</strong> and Kenya<br />

Box 5.4 Farms, enterprises and the envir<strong>on</strong>ment in Tanzania 83<br />

Box 5.5 Doing business in S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa, Kenya, <strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong> Tanzania 84<br />

and Rwanda<br />

Box 5.6 The envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>side <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the educati<strong>on</strong> and training system 86<br />

in Rwanda<br />

Box 5.7 Disabling envir<strong>on</strong>ments <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>side <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the educati<strong>on</strong> and training system 87<br />

in Rural <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

Box 5.8 The relati<strong>on</strong>ship between educati<strong>on</strong> and the ec<strong>on</strong>omy in Kenya 88<br />

DFID vii

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

Acr<strong>on</strong>yms and Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

AAU Associati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> African Universities<br />

DFID Department for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development<br />

EFA Educati<strong>on</strong> for All<br />

ESSP Educati<strong>on</strong> Sector Support Project<br />

ESSU Educati<strong>on</strong> Sector Strategy Update<br />

GDP Gross Domestic Product<br />

GER Gross Enrolment Ratio<br />

GoI Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>India</strong><br />

GoG Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>Ghana</strong><br />

GoK Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenya<br />

GoR Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rwanda<br />

GoRSA Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Republic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

GoURT Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the United Republic <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tanzania<br />

HDI Human Development Index<br />

HIPC Heavily Indebted Poor Country<br />

HPI Human <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> Index<br />

ICCES Integrated Community Centres for Employable Skills<br />

ICT Informati<strong>on</strong> and Communicati<strong>on</strong>s Technology<br />

ILO Internati<strong>on</strong>al Labour Organisati<strong>on</strong><br />

MDG Millennium Development Goal<br />

MSE Micro- and Small-Enterprise<br />

NER Net Enrolment Ratio<br />

NFET N<strong>on</strong>-Formal Educati<strong>on</strong> and Training<br />

NGO N<strong>on</strong>-governmental Organisati<strong>on</strong><br />

PBET Post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> and training<br />

PPA Participatory <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> Appraisal<br />

PRSP <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g> Reducti<strong>on</strong> Strategy Paper<br />

RORE Rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Return to Educati<strong>on</strong><br />

SIDA/Sida Swedish Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development Cooperati<strong>on</strong> Agency<br />

SME Small and Medium Enterprise<br />

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa<br />

STEP Skills Training and Entrepreneurship Programme<br />

TIVET Technical, Industrial, Vocati<strong>on</strong>al and Entrepreneurship Training (Kenya)<br />

TVET Technical and Vocati<strong>on</strong>al Educati<strong>on</strong> and Training<br />

UNESCO United Nati<strong>on</strong>s Educati<strong>on</strong>al, Scientific and Cultural Organisati<strong>on</strong><br />

UPE Universal Primary Educati<strong>on</strong><br />

USAID United States Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development<br />

VETA Vocati<strong>on</strong>al Educati<strong>on</strong> and Training Authority (Tanzania)<br />

viii DFID

Executive Summary<br />

1. Background to the research<br />

Executive Summary<br />

This research project has explored the ways in which both the achievement and the<br />

developmental impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the goal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Universal Primary Educati<strong>on</strong> (UPE) rely <strong>on</strong> strengthening<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> systems for post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> and training (PBET). Reviewing the relevant policies,<br />

instituti<strong>on</strong>s, and experience in six countries (<strong>India</strong>, <strong>Ghana</strong>, Rwanda, Kenya, S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa,<br />

Tanzania), we have sought policy-relevant less<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>cerning the ways in which the povertyreducing<br />

benefits <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> basic educati<strong>on</strong> depend <strong>on</strong> PBET’s c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s to an enabling<br />

envir<strong>on</strong>ment in two broad ways:<br />

• a delivery c<strong>on</strong>text in which basic educati<strong>on</strong> can flourish (essentially a questi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

quality and sustainability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong>al provisi<strong>on</strong> across the whole educati<strong>on</strong> sector);<br />

• a transformative c<strong>on</strong>text which facilitates translati<strong>on</strong> from basic and post-basic educati<strong>on</strong><br />

into developmental <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes (essentially a questi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the developmental value <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

educati<strong>on</strong> for individuals and for society in general).<br />

Obvious though these interdependencies may seem, our starting-point is the problematic lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

reference to PBET in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and the related trends<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g some internati<strong>on</strong>al d<strong>on</strong>ors and country strategies towards an under-emphasis <strong>on</strong> PBET<br />

in development policy and even in budgetary provisi<strong>on</strong>, and towards an over-emphasis <strong>on</strong> the<br />

importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rapid progress towards achieving UPE regardless <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its sustainability and<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes. We also identify as a critical problem the naïve use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> research knowledge to support<br />

unwarranted assumpti<strong>on</strong>s ab<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> simple translati<strong>on</strong>s from primary educati<strong>on</strong>al inputs to<br />

developmental <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes. Our aim is therefore to promote more sophisticated and holistic use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

research in developing and implementing policies for educati<strong>on</strong> and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

2. Linking educati<strong>on</strong>, skills and c<strong>on</strong>text<br />

In Chapter 2 we present our framework for the analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the links between educati<strong>on</strong>, skills<br />

training and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>. This framework highlights the indirect role that post-basic<br />

educati<strong>on</strong> and training may have in ensuring that the potential benefits <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> basic educati<strong>on</strong> are<br />

realised, through supporting the delivery c<strong>on</strong>text and the transformative c<strong>on</strong>text. We explore the<br />

importance and the nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the transformative c<strong>on</strong>text using the example <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the ‘farmer<br />

educati<strong>on</strong> fallacy’. The link between farmer educati<strong>on</strong> and productivity is widely accepted, but<br />

less attenti<strong>on</strong> is given to the fact that this link <strong>on</strong>ly works when people can apply knowledge and<br />

skills to improve agricultural systems in flexible ways. The slogan that ‘four years <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong><br />

increases agricultural productivity’ hides the complexity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this relati<strong>on</strong>ship and implicitly denies<br />

the importance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the transformative c<strong>on</strong>text. In reality, educati<strong>on</strong> makes little difference to<br />

agricultural productivity in c<strong>on</strong>texts that are not favourable to agricultural innovati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

More broadly, we explore the multiple meanings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> in order to<br />

help clarify what might be understood by educati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s to poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>. Since<br />

poverty is multidimensi<strong>on</strong>al, the assessment <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong>/training impacts <strong>on</strong> income al<strong>on</strong>e will<br />

not be satisfactory. Further, since educati<strong>on</strong>al impacts are achieved via complex social processes<br />

and not just through the ‘human development’ improvements in individuals’ skills, claims that<br />

DFID ix

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

educati<strong>on</strong>al policies and systems are targeting the poor or are ‘pro-poor’ tell us little ab<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> their<br />

comparative value in combating poverty. L<strong>on</strong>g-term poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> strategies require a mix<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> targeted pro-poor educati<strong>on</strong>al provisi<strong>on</strong> plus general improvements in educati<strong>on</strong> for all.<br />

3. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>, skills and development<br />

Chapter 3 delves further into the definiti<strong>on</strong>s and interpretati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty, and related c<strong>on</strong>cepts<br />

such as vulnerability and inequality, that are actually deployed in practice in the six study<br />

countries. It explores the ways in which nati<strong>on</strong>al and internati<strong>on</strong>al policies and strategies interact<br />

to produce theories <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> how educati<strong>on</strong> and training might c<strong>on</strong>tribute to poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> and<br />

development in specific c<strong>on</strong>texts. In some countries, notably Rwanda and <strong>Ghana</strong>, there are clear<br />

signs <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tensi<strong>on</strong> between the competing views <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> internati<strong>on</strong>al d<strong>on</strong>ors and nati<strong>on</strong>al governments<br />

<strong>on</strong> optimal approaches to educati<strong>on</strong> and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

We review the comm<strong>on</strong> patterns in the incidence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty in the countries studied, as well as<br />

the diversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the historical factors that have caused it. A key picture emerging is the necessity<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> trade-<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fs between strategies for trying to reduce poverty relatively directly by targeting poor<br />

people in poor areas, and trying to reduce it via more complex indirect mechanisms involving<br />

‘pro-poor’ ec<strong>on</strong>omic growth or more inclusive ec<strong>on</strong>omic growth strategies. <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, and<br />

Tanzania are shown to have l<strong>on</strong>g histories <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> close policy attenti<strong>on</strong> to educati<strong>on</strong> and poverty<br />

reducti<strong>on</strong> in nati<strong>on</strong>al development strategies, with<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> any clear evidence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>sequent<br />

achievements in poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Despite a growing global c<strong>on</strong>sensus <strong>on</strong> the multidimensi<strong>on</strong>ality <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty and <strong>on</strong> the<br />

complexities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>, in policy and practice there is a tendency to categorise<br />

poverty simplistically in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the minimum income required to satisfy basic needs, and<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sequently to see poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> largely in terms <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> enabling poor people to improve their<br />

income. We also note the gulf between theoretical poverty c<strong>on</strong>cepts current am<strong>on</strong>g internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

and nati<strong>on</strong>al-level policy-makers, and the ways in which ordinary people think ab<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty.<br />

4. Research evidence from the six countries<br />

Chapter 4 brings together the research evidence from the six country studies and compares this<br />

with the internati<strong>on</strong>al literature.<br />

Regarding educati<strong>on</strong>al access and quality in the provisi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> and training,<br />

there are clear signs in the country studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> str<strong>on</strong>g bias towards children from wealthier<br />

families and urban areas. The rural poor need to be assisted through targeted sp<strong>on</strong>sorships and<br />

provisi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> hostels but the allocati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these benefits needs to be corrupti<strong>on</strong> free. The quality<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary educati<strong>on</strong> in poor rural areas needs addressing. State-run and state-supported<br />

technical and vocati<strong>on</strong>al educati<strong>on</strong> and training (TVET) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten does not serve the training needs<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the poorer secti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> society. What countries <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ficially term as ‘basic’ educati<strong>on</strong> may no<br />

l<strong>on</strong>ger be sufficient for employment and further training is generally needed, even for entry into<br />

the informal labour market.<br />

x DFID

Executive Summary<br />

In light <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this evidence <strong>on</strong> access and quality, and in light <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> analysis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> ec<strong>on</strong>omic development<br />

at nati<strong>on</strong>al and sub-nati<strong>on</strong>al levels, it becomes clear that the findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the global and regi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

‘ec<strong>on</strong>omic rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> return’ literature must be interpreted with great cauti<strong>on</strong>. The underlying<br />

assumpti<strong>on</strong> that the ec<strong>on</strong>omic benefits to educati<strong>on</strong> can be estimated from wages overlooks a<br />

vast range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> indirect ec<strong>on</strong>omic benefits to the wider society, which may far <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>weigh wages.<br />

Changes and complexities in the labour market, especially in c<strong>on</strong>texts where regular waged jobs<br />

are an excepti<strong>on</strong> rather than the rule, make the validity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data sets used to estimate rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

return highly dubious. This may partly help to explain the lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>sistency between the<br />

findings <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different studies.<br />

There is some evidence that sec<strong>on</strong>dary educati<strong>on</strong> is associated with the capacity to establish<br />

enterprises that create new employment opportunities. In several <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the countries studied there<br />

are shortages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> high-level skills at the same time as saturati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the labour market at other<br />

levels. This may be indicative <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> problems with the quality and relevance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the educati<strong>on</strong><br />

currently being delivered and poor links with the labour market. The influence that educati<strong>on</strong><br />

levels have <strong>on</strong> agriculture is highly c<strong>on</strong>text-dependent, and in general more educated individuals<br />

tend to be less likely to farm.<br />

Evidence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> links between educati<strong>on</strong> and biophysical data (fertility, mortality rates etc) implies<br />

that the relati<strong>on</strong>ship tends to be more pr<strong>on</strong>ounced after primary level. Internati<strong>on</strong>al and<br />

interstate studies show correlati<strong>on</strong>s between post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> levels and ec<strong>on</strong>omic growth,<br />

poverty levels (negative) and equality.<br />

5. Educati<strong>on</strong>, training and enabling envir<strong>on</strong>ments<br />

Chapter 5 explores the c<strong>on</strong>cept <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the enabling envir<strong>on</strong>ment in light <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research findings<br />

from the country studies, as discussed in Chapter 4, and the internati<strong>on</strong>al studies discussed in<br />

Chapter 2. We argue that the politically attractive claims that schooling directly ‘makes a<br />

difference’ to productivity need to be qualified in two ways. First, these allegedly developmental<br />

effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> schooling are almost certainly dependent <strong>on</strong> other facilitating c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s being present<br />

– in the social, cultural, ec<strong>on</strong>omic and political envir<strong>on</strong>ments. And, sec<strong>on</strong>d, these powerful<br />

impacts claimed <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> educati<strong>on</strong> are unlikely to be present – even in envir<strong>on</strong>mentally promising<br />

c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s – if the quality <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the schooling or <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the skills training is <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a very low quality.<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong>sense would suggest that a school affected by massive teacher absenteeism and low<br />

morale can have little impact <strong>on</strong> other developmental <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes. Furthermore, this chapter notes<br />

that it is essential to questi<strong>on</strong> the capacity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> developing ec<strong>on</strong>omies, and especially their informal<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omies, straightforwardly to realise the positive <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes which are <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten claimed to be<br />

associated with skills development through educati<strong>on</strong> and training. Educati<strong>on</strong> and training<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes are obviously determined by many other things such as the quality <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the educati<strong>on</strong><br />

and training and the state <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the enabling envir<strong>on</strong>ment surrounding schools and<br />

skill centres.<br />

DFID xi

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Educating</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Poverty</str<strong>on</strong>g>? A <str<strong>on</strong>g>Synthesis</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>Ghana</strong>, <strong>India</strong>, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and S<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>h Africa<br />

6. C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

The collected research from this six country study points to the flaws in comm<strong>on</strong>, oversimplified<br />

theories c<strong>on</strong>cerning the relati<strong>on</strong>ship between educati<strong>on</strong> and poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>. We identify five<br />

comm<strong>on</strong> fallacies:<br />

• the Causal fallacy: that increased primary educati<strong>on</strong> itself causes poverty reducti<strong>on</strong>;<br />

• the Human Development fallacy: that educati<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s to poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> are<br />

best understood within the ‘human development’ paradigm which focuses <strong>on</strong> individuals’<br />

knowledge and skills;<br />

• the Insular fallacy: that primary educati<strong>on</strong> systems are relatively self-c<strong>on</strong>tained;<br />

• the Pro-poor fallacy: that ‘pro-poor’ educati<strong>on</strong>al provisi<strong>on</strong>ing means focusing <strong>on</strong> primary<br />

educati<strong>on</strong>, and that ‘pro-poor’ is syn<strong>on</strong>ymous with ‘anti-poverty’;<br />

• the Sprint-to-the finish fallacy: that rapid progress towards UPE is necessarily a good thing.<br />

Primary educati<strong>on</strong> can lead to poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> but <strong>on</strong>ly if the delivery c<strong>on</strong>text and<br />

transformative c<strong>on</strong>text are supportive. The development <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these c<strong>on</strong>texts is dependent, am<strong>on</strong>g<br />

other factors, <strong>on</strong> their being a sufficient level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> and training in the country.<br />

Equitable access to Post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> and training can benefit poor communities even if it is<br />

not universal but currently many barriers exist that prevent certain communities from<br />

accessing it.<br />

xii DFID

Chapter 1: Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

1.1 Background<br />

Chapter 1: Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Since their adopti<strong>on</strong> in 2000, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 1 have become a<br />

focus for many bilateral and multilateral development agencies. The MDGs include two<br />

educati<strong>on</strong> targets (targets 3 and 4) that are c<strong>on</strong>cerned with universal primary educati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

gender parity. 2 These reflect thinking within the World Bank, and other multilateral and bilateral<br />

agencies, that educati<strong>on</strong>, and particularly primary educati<strong>on</strong>, has a powerful relati<strong>on</strong>ship with<br />

many other development <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes, and, through these, with the reducti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> poverty more<br />

generally. Statements regarding the ‘developmental’ impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> basic educati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> almost every<br />

other millennium goal are found in Chapter 1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Educati<strong>on</strong> for All (EFA) Global<br />

M<strong>on</strong>itoring <str<strong>on</strong>g>Report</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2002 (UNESCO, 2002), ‘Educati<strong>on</strong> for all is development’.<br />

Nowhere in the MDGs is post-basic educati<strong>on</strong> and training (PBET) 3 menti<strong>on</strong>ed. Only with<br />

regard to gender parity is sec<strong>on</strong>dary educati<strong>on</strong> menti<strong>on</strong>ed. Hence, the educati<strong>on</strong>al emphasis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the MDGs is obviously basic/primary educati<strong>on</strong>. A straightforward interpretati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the MDGs<br />

could thus lead to a policy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> diverting educati<strong>on</strong>al assistance funds towards basic educati<strong>on</strong><br />

and away from PBET. Indeed, many d<strong>on</strong>ors currently channel the majority <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> their aid for<br />

educati<strong>on</strong> into achieving the two educati<strong>on</strong> MDGs. For example, DFID allocates ab<str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g> 80% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

its aid for educati<strong>on</strong> to basic and primary levels (DFID, 2000: 36). 4 In 2001-2002, USAID<br />

allocated 72% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> total educati<strong>on</strong> funding to basic educati<strong>on</strong> (UNESCO, 2004: 191).<br />

Less<strong>on</strong>s are now emerging, however, to suggest that a more balanced approach to educati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

funding is required. PBET plays a crucial role in the realisati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> basic educati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>out</str<strong>on</strong>g>comes, as<br />

well as playing a direct and indirect role in sustainable poverty reducti<strong>on</strong> and the achievement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the MDGs. C<strong>on</strong>sequently, the withdrawal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> funding from these sectors could be<br />