- Page 1 and 2: Mesoweb Publications POPOL VUH Sacr

- Page 3 and 4: modern usage were invaluable. I pur

- Page 5 and 6: aqän us (mosquito legs) who was vi

- Page 7 and 8: The word he used was k'astajisaj, m

- Page 9 and 10: origin, transforming the poet into

- Page 11 and 12: the Indians from their former relig

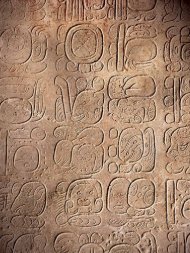

- Page 13 and 14: Maya such that few are literate in

- Page 15 and 16: text that have been published. In t

- Page 17 and 18: newcomers, led by the Cavec-Quiché

- Page 19 and 20: Cavec Quiché lineage that produced

- Page 21 and 22: As outlined in the text, the Quich

- Page 23 and 24: Precolumbian Popol Vuh: In the prea

- Page 25 and 26: Popol Vuh was based as an ilb'al, m

- Page 27 and 28: missionaries. During the early deca

- Page 29 and 30: History of the Popol Vuh Manuscript

- Page 31 and 32: had long since eclipsed Santa Cruz

- Page 33: script arranged in two columns, Qui

- Page 37 and 38: 7. Epithetic Parallelism: The assoc

- Page 39 and 40: Masker, K'ojaj, Sun Lord, K'enech A

- Page 41 and 42: Merely shaped they are called. Xa b

- Page 43 and 44: Come here then my work, Sa'j la rec

- Page 45 and 46: Orthography: The Quiché version of

- Page 47 and 48: Since the sixteenth century, a numb

- Page 49 and 50: throat is closed and air forcefully

- Page 51 and 52: Here we shall gather the manifestat

- Page 53 and 54: These collectively are evoked and g

- Page 55 and 56: Shelterer, 29 Twice Midwife and Twi

- Page 57 and 58: sides, 40 as it is said, by the Fra

- Page 59 and 60: Quetzal Serpent. In their essence,

- Page 61 and 62: “How shall it be sown? When shall

- Page 63 and 64: sky was set apart. The earth also w

- Page 65 and 66: Heart of Sky and Heart of Earth, Fr

- Page 67 and 68: Then was the framing, the making of

- Page 69 and 70: it be sown. May it dawn so that we

- Page 71 and 72: If this is to be the provider and t

- Page 73 and 74: who had given them birth and given

- Page 75 and 76: Thus they caused the face of the ea

- Page 77 and 78: Then spoke also their griddles and

- Page 79 and 80: “I am great. I dwell above the he

- Page 81 and 82: 161 Yiqoxik is literally “to be s

- Page 83 and 84: Zipacna was he that sustained the g

- Page 85 and 86:

pellet straight from his blowgun in

- Page 87 and 88:

“They are not, thou lord. These a

- Page 89 and 90:

THE DEEDS OF ZIPACNA AND THE FOUR H

- Page 91 and 92:

“How far are you into it?” he w

- Page 93 and 94:

On the third day, they started in o

- Page 95 and 96:

“Please take pity on me. I will n

- Page 97 and 98:

It was simply because of Hunahpu an

- Page 99 and 100:

Then the boys used a twist drill to

- Page 101 and 102:

and Xbalanque. But we shall tell on

- Page 103 and 104:

Now it was on the path leading to X

- Page 105 and 106:

These, then, are they whose names a

- Page 107 and 108:

These messengers were the owls 249

- Page 109 and 110:

THE DESCENT OF ONE HUNAHPU AND SEVE

- Page 111 and 112:

Thus the Xibalbans laughed again. T

- Page 113 and 114:

Thus there are many trials in Xibal

- Page 115 and 116:

Thus they restricted themselves. Al

- Page 117 and 118:

“Thus may it be so, as I have don

- Page 119 and 120:

man.” 283 “Who is responsible f

- Page 121 and 122:

Thus she collected the sap, the sec

- Page 123 and 124:

“From where have you come? Do my

- Page 125 and 126:

Thus she called upon the guardians

- Page 127 and 128:

Thus she went to see the maize plan

- Page 129 and 130:

Thus they were ignored 327 by Hunah

- Page 131 and 132:

“Our birds do not fall down here.

- Page 133 and 134:

THE FALL OF ONE BATZ AND ONE CHOUEN

- Page 135 and 136:

“We tried, our grandmother, and a

- Page 137 and 138:

Then they gave instructions to an a

- Page 139 and 140:

The first of these were the puma an

- Page 141 and 142:

Straightaway you will go up to wher

- Page 143 and 144:

Immediately then they sealed it, an

- Page 145 and 146:

“Very well then, but I see that y

- Page 147 and 148:

“Tell it then,” they said to th

- Page 149 and 150:

Thus Hunahpu planted one, and Xbala

- Page 151 and 152:

“What, Skull Staff? What is it?

- Page 153 and 154:

Thus they entered first into the Ho

- Page 155 and 156:

Thus the Xibalbans threw down their

- Page 157 and 158:

“Look after our flowers with all

- Page 159 and 160:

HUNAHPU AND XBALANQUE IN THE HOUSE

- Page 161 and 162:

Thus they pleaded for wisdom all th

- Page 163 and 164:

“Fine,” replied the Grandfather

- Page 165 and 166:

Thus the twins were able to retriev

- Page 167 and 168:

“You will then reply, ‘Certainl

- Page 169 and 170:

THE RESURRECTION OF HUNAHPU AND XBA

- Page 171 and 172:

to be prodded because they just wal

- Page 173 and 174:

“Now kill a person. Sacrifice him

- Page 175 and 176:

And then they declared their names.

- Page 177 and 178:

called masters of harm 441 and vexa

- Page 179 and 180:

then little more was said. He did n

- Page 181 and 182:

THESE were the names of the animals

- Page 183 and 184:

called Paxil and Cayala came the sw

- Page 185 and 186:

THE MIRACULOUS VISION OF THE FIRST

- Page 187 and 188:

to move about. We know much, for we

- Page 189 and 190:

eginning. 495 Thus were the framing

- Page 191 and 192:

The beginning of the Tamub and the

- Page 193 and 194:

Uchabahas 517 and the Ah Chumilahas

- Page 195 and 196:

of Sky, Heart of Earth. May our sig

- Page 197 and 198:

THE ARRIVAL AT TULAN 546 THIS, then

- Page 199 and 200:

Nicacah Tacah 554 was the name of t

- Page 201 and 202:

their fire came to nought. Then Bal

- Page 203 and 204:

THE NATIONS ARE DECEIVED INTO OFFER

- Page 205 and 206:

Now when they came from Tulan Zuyva

- Page 207 and 208:

mountain today is called Chi Pixab.

- Page 209 and 210:

Mahucutah, who observed a great fas

- Page 211 and 212:

came to be. Hacavitz it was called.

- Page 213 and 214:

But these, the gods, were comforted

- Page 215 and 216:

the Cakchiquels, the Ah Tziquinahas

- Page 217 and 218:

This they sang concerning the blood

- Page 219 and 220:

them. They gave thanks before them

- Page 221 and 222:

They did the same before the deersk

- Page 223 and 224:

“Conquer many lands. This is your

- Page 225 and 226:

There was a river where they would

- Page 227 and 228:

our hearts that they have come unto

- Page 229 and 230:

of Tohil. Thus said Tohil, Auilix,

- Page 231 and 232:

For the lords felt it was the sign

- Page 233 and 234:

THE NATIONS ARE HUMILIATED 656 THUS

- Page 235 and 236:

mere carved wood with the precious

- Page 237 and 238:

Thus they became disoriented 668 be

- Page 239 and 240:

Balam Acab of the Nihaibs also had

- Page 241 and 242:

disappearance clear when they vanis

- Page 243 and 244:

their lordship. Thus they received

- Page 245 and 246:

THE MIGRATIONS OF THE QUICHÉS 705

- Page 247 and 248:

Then they investigated the mountain

- Page 249 and 250:

There were only two swollen 722 gre

- Page 251 and 252:

And yet again they began to feast a

- Page 253 and 254:

with one another and split apart. T

- Page 255 and 256:

Councilor of the Stacks; 744 Emissa

- Page 257 and 258:

Lord Emissary; 760 Great Lord Stewa

- Page 259 and 260:

Cucumatz became a truly enchanted l

- Page 261 and 262:

name of the other. These accomplish

- Page 263 and 264:

arrows that were the means of shatt

- Page 265 and 266:

Along with Ah Cabracan, 797 Chabi C

- Page 267 and 268:

united. 811 The Tamub and the Iloca

- Page 269 and 270:

Nihaibs. 822 Auilix was the name of

- Page 271 and 272:

of Tohil, as well as before the fac

- Page 273 and 274:

you place them on green roads and o

- Page 275 and 276:

Nor was it merely a few of the nati

- Page 277 and 278:

Tecum 851 and Tepepul were the nint

- Page 279 and 280:

Tecum 860 and Tepepul 861 paid trib

- Page 281 and 282:

THE GREAT HOUSES OF THE CAVEC LORDS

- Page 283 and 284:

THE DYNASTY OF NIHAIB LORDS 869 THE

- Page 285 and 286:

THE DYNASTY OF AHAU QUICHÉ LORDS 8

- Page 287:

But this is the essence of the Quic