Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya - Mesoweb

Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya - Mesoweb

Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya - Mesoweb

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

PREAMBLE 1<br />

POPOL VUH<br />

THIS IS THE BEGINNING 2 OF THE ANCIENT TRADITIONS 3 <strong>of</strong> this place<br />

called <strong>Quiché</strong>. 4<br />

HERE we shall write. 5 We shall begin 6 to tell <strong>the</strong> ancient stories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> beginning,<br />

<strong>the</strong> origin <strong>of</strong> all that was done in <strong>the</strong> citadel 7 <strong>of</strong> <strong>Quiché</strong>, among <strong>the</strong> people <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Quiché</strong><br />

nation. 8<br />

1 lines 1-96<br />

2 The <strong>Quiché</strong> word xe' (root) is used here to describe <strong>the</strong> beginning or foundation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors’ words<br />

concerning <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Quiché</strong> people. The subsequent narrative is thus seen as growing like a plant<br />

from this “root” (lines 4-6).<br />

3 The <strong>Popol</strong> <strong>Vuh</strong> manuscript does not utilize capitalization or punctuation to differentiate sentences.<br />

Capitalization is, however, used to mark <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> what <strong>the</strong> authors consider to be <strong>the</strong> major<br />

divisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir story. In general, only <strong>the</strong> first word <strong>of</strong> each new section is capitalized. In this translation,<br />

I have marked <strong>the</strong>se divisions by capitalizing <strong>the</strong> first word <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> introductory line where appropriate. In<br />

two instances (lines 1 and 97), <strong>the</strong> entire introductory line is capitalized in <strong>the</strong> manuscript. Line 1<br />

introduces <strong>the</strong> preamble <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> text, while line 97 is <strong>the</strong> first line <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> story itself.<br />

4 The authors at various times refer to <strong>the</strong> land, <strong>the</strong> nation, <strong>the</strong> capital city, and <strong>the</strong> people <strong>the</strong>mselves as<br />

<strong>Quiché</strong> (K'iche' in <strong>the</strong> modern orthography <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Maya</strong> languages), meaning “many trees” or “forest.” The<br />

homeland <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Quiché</strong> people in western Guatemala is mountainous and heavily forested.<br />

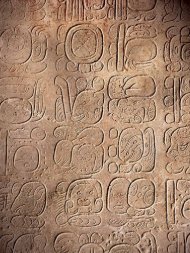

5 The authors here state that <strong>the</strong>y are “writing” this history. The people <strong>of</strong> ancient Mesoamerica (roughly<br />

<strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> Central Mexico southward to Guatemala, Belize, and parts <strong>of</strong> Honduras and El Salvador) were<br />

<strong>the</strong> only literate Precolumbian cultures in <strong>the</strong> New World. Following <strong>the</strong> Spanish conquest, native<br />

Americans were discouraged from using <strong>the</strong>ir own ancient writing systems in favor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Latin script. The<br />

manuscript <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Popol</strong> <strong>Vuh</strong> was thus written in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Maya</strong>n language <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Quiché</strong>s, but with a European<br />

script. It is this set <strong>of</strong> circumstances that has preserved <strong>the</strong> <strong>Popol</strong> <strong>Vuh</strong> in a fully readable form when so<br />

many o<strong>the</strong>r native American texts were ei<strong>the</strong>r destroyed or written in an as yet incompletely decipherable<br />

glyphic form.<br />

6 Tikib'a' is literally “to plant.” “The beginning,” also in this sentence, is <strong>the</strong>refore literally “<strong>the</strong><br />

planting.”<br />

7 Based on tinamit, a Nahua-derived word meaning “fortified town, citadel, or fortification wall”<br />

(Campbell 1983, 85). Although in modern <strong>Quiché</strong>, tinamit simply refers to a town or city, <strong>the</strong> word is used<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Popol</strong> <strong>Vuh</strong> text to specify fortified centers occupied by ruling lineages (Carmack 1981, 23). Here <strong>the</strong><br />

citadel <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Quiché</strong> people is also called <strong>Quiché</strong>, apparently referring to <strong>the</strong> heartland region <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

nation. This would include <strong>the</strong> capital city, Cumarcah, as well as its surrounding territory.<br />

50