Physical Density and Urban Sprawl: A Case of Dhaka City - KTH

Physical Density and Urban Sprawl: A Case of Dhaka City - KTH

Physical Density and Urban Sprawl: A Case of Dhaka City - KTH

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>KTH</strong> Architecture <strong>and</strong><br />

the Built Environment<br />

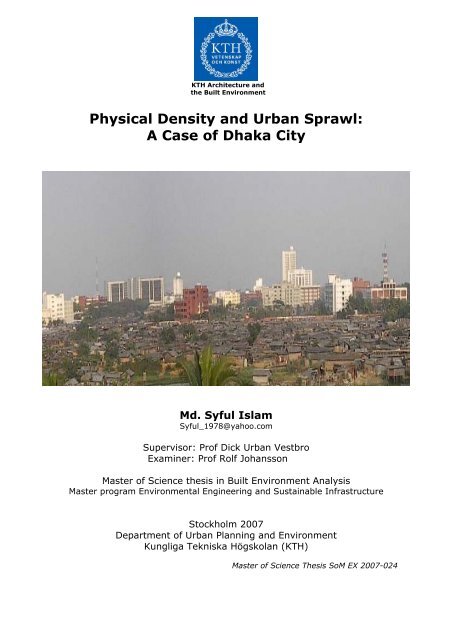

<strong>Physical</strong> <strong>Density</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Sprawl</strong>:<br />

A <strong>Case</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> <strong>City</strong><br />

Md. Syful Islam<br />

Syful_1978@yahoo.com<br />

Supervisor: Pr<strong>of</strong> Dick <strong>Urban</strong> Vestbro<br />

Examiner: Pr<strong>of</strong> Rolf Johansson<br />

Master <strong>of</strong> Science thesis in Built Environment Analysis<br />

Master program Environmental Engineering <strong>and</strong> Sustainable Infrastructure<br />

Stockholm 2007<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> Planning <strong>and</strong> Environment<br />

Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan (<strong>KTH</strong>)<br />

Master <strong>of</strong> Science Thesis SoM EX 2007-024

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

ABSTRACT..........................................................................................................................iv<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .....................................................................................................v<br />

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................1<br />

1.1 Real life problem..............................................................................................................1<br />

1.2 Lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge...........................................................................................................2<br />

1.3 Aim <strong>and</strong> Objectives..........................................................................................................3<br />

1.4 Methodology....................................................................................................................3<br />

1.4.1 Research design ........................................................................................................3<br />

1.4.3 Data collection methods............................................................................................7<br />

1.4.4 Summary <strong>of</strong> the study issues <strong>and</strong> used methods.....................................................10<br />

CHAPTER 2:THEORY OF THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK...............................11<br />

2.1 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Sprawl</strong> .................................................................................................................11<br />

2.2 <strong>Physical</strong> density .............................................................................................................12<br />

2.2.1 Measurement <strong>of</strong> physical densities .........................................................................14<br />

2.3 Plot characteristics <strong>and</strong> configurations ..........................................................................16<br />

2.4 Spatial qualities..............................................................................................................17<br />

2.5 Informal Settlements......................................................................................................18<br />

CHAPTER 3: THE DEVELOPMENT OF DHAKA……………………………………..20<br />

3.1 Introduction <strong>of</strong> the study area ........................................................................................20<br />

3.2 <strong>Physical</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city from 1700 till 1995 .............................................20<br />

3.3 <strong>Urban</strong>ization in Bangladesh <strong>and</strong> population growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city...............................22<br />

3.4 <strong>Urban</strong>ization <strong>and</strong> housing situation in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city.........................................................23<br />

3.5 L<strong>and</strong> use pattern <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city ......................................................................................25<br />

3.6 <strong>Density</strong> <strong>and</strong> Housing supply system..............................................................................26<br />

3.7 <strong>Density</strong> <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong> supply in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city.........................................................................28<br />

3.8 Planned <strong>and</strong> unplanned housing in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city..............................................................29<br />

3.9 Informal settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city................................................................................30<br />

3.9.1 Location <strong>of</strong> informal settlements ............................................................................31<br />

3.9.2 Ratio <strong>of</strong> the population in the formal <strong>and</strong> formal settlements ................................32<br />

3.9.3 Owner ship pattern <strong>of</strong> informal settlements............................................................34<br />

CHAPTER 4: FINDINGS FROM THE INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS ........................35<br />

4.1 Geneva Camp in Mohammadpur thana .........................................................................35<br />

4.2 ‘Tikkapara Bustee’ in Mohammadpur thana .................................................................41<br />

CHAPTER 5: FINDINGS FROM THE FORMAL SETTLEMENTS.............................46<br />

5.1 Road number 3 at Dhanmondi residential area..............................................................46<br />

5.2 Shobhanbagh <strong>of</strong>ficers’ colony .......................................................................................47<br />

5.3 Baridhara residential area ..............................................................................................47<br />

5.4 Banani model town residential area...............................................................................48<br />

5.5 Block at Mirpur 10 number circle residential area in Mirpur thana ..............................49<br />

5.6 Newly planned Defense Officers’ Housing Society (DOHS) at Baridhara in Gulshan 50<br />

i

CHAPTER 6: FINAL ANALYSIS......................................................................................51<br />

6.1 <strong>Physical</strong> densities...........................................................................................................51<br />

6.2 Spatial qualities..............................................................................................................52<br />

6.3 Relationship <strong>Urban</strong> sprawl <strong>and</strong> physical densities.........................................................54<br />

CHAPTER 7: RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION........................................55<br />

7.1 Recommendations..........................................................................................................55<br />

7.2 Conclusion .....................................................................................................................56<br />

REFERENCES.......................................................................................................................58<br />

LIST OF FIGURES<br />

Figure 1.1 Procedure <strong>of</strong> block selection 6<br />

Figure 1.2 Location <strong>of</strong> case areas 7<br />

Figure 1.3 The diagrammatic presentation <strong>of</strong> the height calculation 10<br />

Figure 1.4 Procedure <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage calculation 11<br />

Figure 1.5 Calculation <strong>of</strong> total floor area occupied by individual building 12<br />

Figure 1.6 Summary <strong>of</strong> study aspects <strong>and</strong> methods 12<br />

Figure 2.1 Advantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages <strong>of</strong> High vs Low density. 14<br />

Figure 2.2 Influences on density 15<br />

Figure 2.3 conceptual model <strong>of</strong> FAR values <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage 16<br />

Figure 2.4 <strong>Density</strong> <strong>of</strong> several urban blocks in Sweden 17<br />

Figure 2.5 <strong>Urban</strong> density, building height <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> built-up area in eight 18<br />

Figure 2.6 Plot area, ratio <strong>and</strong> exposure 19<br />

Figure 2.7 Cluster <strong>of</strong> Informal settlement in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city 20<br />

Figure 3.1 <strong>Physical</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city from 1700 till 1995 23<br />

Figure 3.2 View showing the dense settlements <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> 26<br />

Figure 3.3 Low dense informal settlements just beside the formal settlements 26<br />

Figure 3.4 L<strong>and</strong> use pattern <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city 27<br />

Figure 3.5 Housing supply system <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city 29<br />

Figure 3.6 L<strong>and</strong> supply sub system in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city 30<br />

Figure 3.7 Planned <strong>and</strong> unplanned housing <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city during the year 2004 32<br />

Figure 3.8 Location <strong>of</strong> informal settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong>, 1996 34<br />

Figure 3.9 Ratio <strong>of</strong> formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements population by thana 35<br />

Figure 4.1 Satellite image <strong>of</strong> Geneva camp 37<br />

Figure 4.2 Houses are very close to each other 38<br />

Figure 4.3 Very narrow road width inside the block 38<br />

Figure 4.4 The internal roads are using for drying their clothes 39<br />

Figure 4.5 A woman is cooking in the outdoor by using soil burner 39<br />

Figure 4.6 A woman is cutting her fish in the corridor 40<br />

Figure 4.7 Inhabitants are selling their groceries in the footpath 40<br />

Figure 4.8 Container in the surrounding footpath 41<br />

Figure 4.9 Washing clothes <strong>and</strong> taking shower between the space <strong>of</strong> two houses 41<br />

Figure 4.10 children are playing in the space between the buildings 42<br />

Figure 4.11 Social interaction <strong>of</strong> inhabitants in the footpath 42<br />

Figure 4.12 Open the ro<strong>of</strong>’s tin to get fresh air 43<br />

Figure 4.13 The physical density <strong>of</strong> houses inside the block 44<br />

Figure 4.14 Space between the houses 44<br />

ii

Figure 4.15 The space inside the houses 45<br />

Figure 4.16 A woman is cooking inside the living room 45<br />

Figure 4.17 The space is used by tube well as a source <strong>of</strong> water supply 46<br />

Figure 4.18 Very narrow internal road <strong>and</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> window 46<br />

Figure 5.1 Aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> Road number 3 in Dhanmondi area 48<br />

Figure 5.2 Aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> Shobhanbagh <strong>of</strong>ficers’ colony at Shobhanbagh in 49<br />

Figure 5.3 Aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> Baridhara residential area at Gulshan thana 50<br />

Figure 5.4 Aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> block at Banani Model town in Gulshan thana 51<br />

Figure 5.5 Aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> block at Mirpur 10 number circle in Mirpur thana 51<br />

Figure 5.6 Aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> New DOHS at Baridhara area in Gulshan thana 52<br />

LIST OF TABLES<br />

Table 3.1 <strong>Urban</strong>ization in Bangladesh <strong>and</strong> urban Population growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city 25<br />

Table 3.2 Population growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city <strong>and</strong> the requirement <strong>of</strong> new shelters. 25<br />

Table 3.3 Amount <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> use for different purposes in the mega city (percentage) 28<br />

Table 3.4 Distribution <strong>of</strong> Open Spaces in DCC 28<br />

Table 3.5 Apartment sizes in different areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city 30<br />

Table 3.6 RAJUK’s provided Plots size, quantity <strong>and</strong> their price 31<br />

Table 3. 7 Owner ship pattern <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> 36<br />

ACRONYMS<br />

DCC <strong>Dhaka</strong> <strong>City</strong> Corporation<br />

RAJUK Rajdhani Unnayan Kartipakkha (Capital Development Authority)<br />

FAR Floor Area Ratio<br />

JICA Japan International Cooperation Authority<br />

CUS Center for <strong>Urban</strong> Studies<br />

LGED Local Government Engineering Department<br />

BBS Bangladesh Bureau <strong>of</strong> Stastics<br />

DOHS Defense Officers’ Housing Society<br />

BNBC Bangladesh National Building Code<br />

REHAB Real Estate <strong>and</strong> Housing Association <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh<br />

UNDP United Nations Development Programme<br />

UNCPF United Nations Capital Development Fund<br />

NHA National Housing Authority<br />

CBD Central Business District<br />

DMA <strong>Dhaka</strong> Metropolitan Authority<br />

iii

ABSTRACT<br />

Md. Syful Islam: <strong>Physical</strong> <strong>Density</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Sprawl</strong>: A <strong>Case</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> <strong>City</strong><br />

One <strong>of</strong> the contemporary issues in cities <strong>of</strong> low income countries is horizontal expansion due<br />

to the rapid urbanization <strong>and</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> low dense formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements<br />

inside or periphery <strong>of</strong> the city. Despite that the spatial quality <strong>of</strong> those informal settlements<br />

are not mentionable due to the high percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage. There are very few efforts<br />

being applied by planning authorities or pr<strong>of</strong>essionals to analyze, evaluate <strong>and</strong> control<br />

physical densities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements. Similarly there is a knowledge gap associated with<br />

the concept <strong>and</strong> theory to achieve st<strong>and</strong>ard physical densities like st<strong>and</strong>ard floor area ratio<br />

<strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage which can provide good spatial qualities <strong>and</strong> can combat<br />

urban sprawl.<br />

This thesis aims to analyze the physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> formal <strong>and</strong> informal<br />

settlements as well as investigate their relationship to the urban sprawl. As a part <strong>of</strong> this study<br />

<strong>Dhaka</strong>, the capital city <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh has been selected as the case area. The physical<br />

densities have been explored by using Google earth s<strong>of</strong>tware where the spatial qualities have<br />

been analyzed by using photographs. The different blocks <strong>of</strong> formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements<br />

have been selected to analyze the physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities in detail. The floor<br />

area ratio <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings inside the block have been considered<br />

as the variables <strong>of</strong> physical density where the space usability, cross ventilation <strong>and</strong> presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> day light have been considered as the variables <strong>of</strong> spatial quality.<br />

The study shows that the floor area ratio <strong>of</strong> informal settlements is very low <strong>and</strong> the<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by houses is very high. On the other h<strong>and</strong> the floor area ratio <strong>and</strong><br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings in formal settlements are very high except some<br />

high income class areas. A lot <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> is being consumed by informal settlements in spite <strong>of</strong><br />

the very high percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage. The efficiency <strong>of</strong> the space inside the block <strong>of</strong><br />

informal settlements is not good, <strong>and</strong> as a result there is a shortage <strong>of</strong> the variables <strong>of</strong> spatial<br />

quality. The sprawl problem is looked at in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city for the rapid development <strong>of</strong> those<br />

informal settlements inside or periphery <strong>of</strong> the city.<br />

Finally the study has recommended the block type with high dense low height houses inside<br />

the block to increase efficiency <strong>of</strong> the space, ensure day light <strong>and</strong> cross ventilation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

houses which is affordable to the urban low income people.<br />

Key words: <strong>Physical</strong> density, spatial quality, formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements, urban sprawl,<br />

<strong>Dhaka</strong>.<br />

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT<br />

The success <strong>of</strong> this research has become possible through the assistance from a number <strong>of</strong><br />

people, all <strong>of</strong> whom I can not acknowledge. First I am grateful to my supervisor pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

Dick <strong>Urban</strong> Vestbro who has encouraged <strong>and</strong> guided me by providing several books <strong>and</strong><br />

papers regarding to my study. His support, criticism <strong>and</strong> intellectual comments helped me to<br />

accomplish this study.<br />

I would like to thank those who encouraged me to study up to this level. To my parents who<br />

are living in Bangladesh, I say thank you for your parental sacrifice which enabled me to<br />

study in Sweden. Special thanks to my beloved Mahabuba Sultana who has helped me by<br />

providing several <strong>of</strong>ficial documents <strong>and</strong> photographs regarding to my study. Without her<br />

help <strong>and</strong> devotion, it was too difficult for me to collect photographs <strong>and</strong> data on informal<br />

settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city. I also owe similar gratitude to my sisters <strong>and</strong> brothers in<br />

Bangladesh for their committed help to study in Sweden.<br />

I am indebted to the <strong>of</strong>ficials <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> <strong>City</strong> Corporation who have helped me by providing<br />

several important documents. Furthermore thanks also goes to my previous university<br />

teachers in Bangladesh who have helped me by providing their intellectual knowledge about<br />

density <strong>of</strong> the housing settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city. Among them is my former university<br />

teacher Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dr. K.M. Moniruzzaman for his countless knowledge based suggestions.<br />

I also extend collective thanks to my classmates <strong>of</strong> Environmental engineering <strong>and</strong><br />

Sustainable Infrastructure program for their special comments about my work. I would like to<br />

say especial thanks to Michael Bimpeh from Ghana for his kind help to edit my thesis work<br />

properly.<br />

I owe special thanks to Google Earth S<strong>of</strong>tware Company that enabled me to measure the area<br />

<strong>of</strong> block, area <strong>of</strong> buildings, area <strong>of</strong> plots, height <strong>of</strong> buildings <strong>and</strong> width <strong>of</strong> surrounding roads.<br />

Without this s<strong>of</strong>tware it would not have been possible to get those measurements.<br />

All other people who assisted in various capacities, I render my pr<strong>of</strong>ound gratitude to them.<br />

v

CHAPTER 1<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

This study analyses selected formal <strong>and</strong> informal housing blocks <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city. The focus <strong>of</strong><br />

the analysis is on the physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing block addresses urban<br />

sprawl. The formal settlements in the inner part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Dhaka</strong> are densely developed.<br />

However, the area <strong>of</strong> the city is exp<strong>and</strong>ing horizontally because a lot <strong>of</strong> informal settlements<br />

are developing in the inner part or periphery <strong>of</strong> the city. If urban sprawl in <strong>Dhaka</strong> is to be<br />

addressed, housing solution that can accommodate the increasing population <strong>and</strong> with good<br />

spatial qualities is very important. The present study will investigate physical densities <strong>and</strong><br />

spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city <strong>and</strong> recommend such<br />

housing block for urban low income people.<br />

1.1 Real life problem<br />

<strong>Urban</strong> sprawl is one <strong>of</strong> the contemporary issues <strong>of</strong> cities all over the world. It contributes to<br />

the inefficient use <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> resources, energy <strong>and</strong> large scale absorption <strong>of</strong> open space that can<br />

otherwise be used more effectively for activities which can contribute to the development <strong>of</strong> a<br />

city. <strong>Dhaka</strong> is the capital <strong>and</strong> the biggest city <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh which is the main center <strong>of</strong><br />

education, administration, trade <strong>and</strong> commerce. The population is growing rapidly due to the<br />

massive rural urban migration. The city is experiencing an increase in the rate <strong>of</strong> housing<br />

development. The private developers or government housing companies are constructing<br />

houses for the high or middle income people while the low income people do not have<br />

provision in the housing market, though most <strong>of</strong> the people in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city are poor. As a<br />

result a lot <strong>of</strong> informal settlements have developed in the inner part or in the periphery <strong>of</strong> the<br />

city. The development <strong>of</strong> such informal settlements is causing inefficient use <strong>of</strong> space; hence<br />

the city is exp<strong>and</strong>ing horizontally. It is difficult to provide infrastructure facilities to the city<br />

dwellers due to this horizontal expansion. The present study intends to explore the<br />

relationship between the physical densities <strong>of</strong> the housing settlements <strong>and</strong> urban sprawl.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the informal settlements are being developed on the government vacant l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

wetl<strong>and</strong>s inside or in the periphery <strong>of</strong> the city which have been reserved by the government<br />

for different purposes. In order to stop the encroachment by the informal settlers, there is a<br />

need to develop housing block with high physical densities <strong>and</strong> good spatial qualities.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the informal settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city are comprised <strong>of</strong> single storied houses <strong>and</strong><br />

mostly dense due to the close distance among the houses. The usability <strong>of</strong> spaces inside the<br />

block is not efficient because most <strong>of</strong> the spaces inside the block are covered by buildings. In<br />

order to increase the efficiency <strong>of</strong> space there is a need to analyze the physical density, in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> Floor Area Ratio (FAR) <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings. Here FAR<br />

means the ratio between the built up area <strong>and</strong> the total l<strong>and</strong> area including communal spaces<br />

<strong>and</strong> streets belonging to the block.<br />

The close distance among the houses <strong>and</strong> inefficient use <strong>of</strong> spaces inside the block hinder the<br />

spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> the houses. The analysis <strong>of</strong> spatial qualities, in terms <strong>of</strong> cross ventilation,<br />

provision <strong>of</strong> daylight <strong>and</strong> possibility to use outdoor space inside the block are necessary to<br />

recommend the housing block with good spatial qualities<br />

On the other h<strong>and</strong> most <strong>of</strong> the people in the informal housing settlements are poor. They are<br />

not able to afford high cost houses. So there is a need to recommend houses which are low in<br />

cost <strong>and</strong> can be affordable by the urban low income people.<br />

1

1.2 Lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge<br />

The lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge on the physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements<br />

as well as their impact on urban sprawl can be seen in the most cities all over the world. The<br />

study aims at improving the underst<strong>and</strong>ing among the scholars who are generating methods<br />

<strong>and</strong> theories about the physical densities, spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> informal housing settlements<br />

which have impact on urban sprawl as well as to reduce the knowledge gap in that field.<br />

There is a lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge on the systematic analyses <strong>of</strong> physical densities <strong>of</strong> housing<br />

settlements <strong>and</strong> their impact on urban sprawl, for instance the analysis <strong>of</strong> density <strong>and</strong> spatial<br />

qualities <strong>of</strong> houses in the informal settlements <strong>and</strong> their impact on expansion <strong>of</strong> city. Lupala<br />

notes that fact for the informal housing settlements <strong>of</strong> Dar es Salam<br />

“the rate at which such settlements have been urbanizing has not been<br />

established. Systematic analyses on the growth, densification <strong>and</strong> inherent<br />

spatial qualities have been lacking. Inadequate knowledge base on house<br />

forms, prevailing densities, space usability <strong>and</strong> plot characteristics that take<br />

place in these settlements have restricted adoption <strong>of</strong> effective planning<br />

inventions” (Lupala,2002:2).<br />

The same knowledge gap, as for example analysis <strong>of</strong> physical densities <strong>and</strong> their impact on<br />

urban sprawl can be seen in Bangladesh, though the urban sprawl is one <strong>of</strong> the vital problems<br />

<strong>of</strong> the cities in Bangladesh.<br />

There is a lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge on the use <strong>of</strong> space, how transformation affects spatial qualities<br />

<strong>and</strong> how people view housing modernization. Despite the fact that there is a wide variety <strong>of</strong><br />

housing in the informal settlements, there is inadequate knowledge <strong>of</strong> what the existing <strong>and</strong><br />

emerging house types are, as a result <strong>of</strong> transformation that could be better developed by<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals like architects <strong>and</strong> planners. Nguluma states that whether the transformed house<br />

types are efficient in terms <strong>of</strong> density, better spatial qualities allowing ventilation <strong>and</strong> enough<br />

light, is also not known (Nguluma, 2003:5). That is why sometimes it is difficult to describe<br />

contemporary housing <strong>and</strong> planning problems in informal settlements.<br />

Nnkya (1999:19) has related the lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge to ineffective planning in Tanzania <strong>and</strong><br />

argues that the lack <strong>of</strong> or too little knowledge on the social, economic <strong>and</strong> political<br />

processes, which shapes the political <strong>and</strong> physical environment has been influential to<br />

defective planning <strong>and</strong> in same instances triggered <strong>of</strong>f disputes between the planning<br />

authorities <strong>and</strong> the stakeholders. This same problem can be seen in Bangladesh even though<br />

the urban types or block types in Tanzania are different from Bangladesh.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the rapidly urbanizing cities <strong>and</strong> their settlements are being developed according to<br />

inherited colonial urban types <strong>and</strong> neighborhood spaces which are yet to be identified,<br />

classified <strong>and</strong> analyzed. While the colonial city reveals some kind <strong>of</strong> regulated patterns <strong>of</strong><br />

city growth as influenced by the formal housing settlements, the post colonial city is largely<br />

unregulated as influenced by the rapid growth <strong>of</strong> informal settlements which also are yet to<br />

be identified <strong>and</strong> analyzed to reduce their expansion by developing physical densities <strong>and</strong><br />

maintaining good spatial qualities (Lupala,2002:2). The formal housing block types <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong><br />

city have also been built up by following different colonial block types <strong>and</strong> most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

informal settlements are being developed in unregulated way without following any block<br />

type. This will be explored in this study.<br />

2

Habraken (1998:292-93) states that, despite the fact that informal housing in developing<br />

countries consistently showing rapid growth <strong>and</strong> change rooted in informal local typologies,<br />

documentation <strong>and</strong> study <strong>of</strong> such informal development has been lacking. There is a<br />

knowledge gap on the documentation <strong>and</strong> study <strong>of</strong> the root <strong>of</strong> informal settlements or their<br />

inherent typologies which have impact on densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> those settlements<br />

The present study will intend to explore the relation between physical densities, spatial<br />

qualities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements <strong>and</strong> urban sprawl as well as to reduce the knowledge gap in<br />

relation to the density, plot characteristics, functionality <strong>of</strong> space, scope <strong>of</strong> cross ventilation<br />

<strong>of</strong> houses <strong>and</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> daylight inside the housing blocks. It can also help the planners to<br />

improve their underst<strong>and</strong>ing in relation to provide housing especially to the poor with the<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard housing density <strong>and</strong> good spatial qualities.<br />

1.3 Aim <strong>and</strong> Objectives<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> this study is to analyse the relationship between physical densities, spatial<br />

qualities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements <strong>and</strong> urban sprawl in <strong>Dhaka</strong>. Therefore the physical densities<br />

<strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> different housing blocks will be studied if they are directly or<br />

indirectly affecting the urban sprawl. Although the blocks <strong>of</strong> formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements<br />

will be studied, the main focus will on the density, space usability, cross ventilation <strong>and</strong><br />

provision <strong>of</strong> daylight in the houses <strong>of</strong> informal settlements. The results <strong>of</strong> the study will lead<br />

to propose block that maintains st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>of</strong> physical densities <strong>and</strong> good spatial qualities <strong>and</strong><br />

that are affordable to the urban low income people.<br />

Objectives<br />

Some objectives have been set to fulfil the above mentioned aim. They are as follows:<br />

! To investigate the relationship between physical densities, spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing<br />

blocks <strong>and</strong> urban sprawl.<br />

! To analyse the physical densities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements, as for example FAR,<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings <strong>and</strong> plot characteristics <strong>of</strong> housing<br />

settlements.<br />

! To analyse spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements, for instance space usability <strong>and</strong><br />

cross ventilation <strong>of</strong> houses emphasizing on informal settlements.<br />

! To explore the impact <strong>of</strong> physical densities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements on urban sprawl<br />

! To recommend block type with good spatial qualities as well as being affordable for<br />

the urban low income people to combat urban sprawl.<br />

1.4 Methodology<br />

To fulfil the objectives <strong>of</strong> the study, various methods were applied. For the calculation <strong>of</strong><br />

physical densities in terms <strong>of</strong> FAR, percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings, plot<br />

characteristics; the measurement <strong>of</strong> block area, l<strong>and</strong> covered by houses, plot sizes, number <strong>of</strong><br />

storeys were calculated from the aerial photographs by using ‘Google Earth’. Previous<br />

personal observations, expert assessments <strong>and</strong> photographs were applied to analyse the space<br />

usability <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing blocks. Literature review <strong>and</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> empirical<br />

studies were carried out from the very early stage <strong>of</strong> the study to gain knowledge about the<br />

relationship between physical densities <strong>and</strong> urban sprawl as well as to establish theories<br />

related to the study.<br />

1.4.1 Research design<br />

The case study research strategy was employed to conduct this present study. Johansson<br />

defines case study “A case study is expected to capture the complexity <strong>of</strong> a single case, which<br />

3

should be a functioning unit, be investigated in its natural context with a multitude <strong>of</strong><br />

methods, <strong>and</strong> be contemporary” (Johansson 2005:31). He further notes that a case study <strong>and</strong>,<br />

normally, history focuses on one case but simultaneously take account <strong>of</strong> the context, <strong>and</strong> so<br />

encompass many variables <strong>and</strong> qualities.<br />

The main aim <strong>of</strong> the study is to explore the relationship between physical densities, spatial<br />

qualities <strong>and</strong> urban sprawl within the context formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city.<br />

Eight housing settlements, six from formal <strong>and</strong> two from informal settlement, <strong>and</strong> their<br />

components <strong>of</strong> physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities were selected. Data was collected <strong>and</strong><br />

analysed for each study area.<br />

1.4.2 Why <strong>Dhaka</strong> is selected as a case areas<br />

The present study regards the physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements<br />

as well as their impact on urban sprawl. <strong>Dhaka</strong> is the capital city <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh.<br />

Approximately, 56% percent <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Dhaka</strong> city’s population lives in informal housing<br />

(Titumir <strong>and</strong> Hossain, 2004). There are 3007 small to large informal housing settlements with<br />

10 or more house clusters covering area <strong>of</strong> 420 hectares in different parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong><br />

(CUS,1996). The built up area is increasing rapidly due to the development <strong>of</strong> informal<br />

settlements in the inner part <strong>and</strong> in the periphery <strong>of</strong> the city. Between 1990 <strong>and</strong> 2000, the<br />

built-up area <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> Metropolitan area has increased by around 46% (JICA Baseline Study,<br />

2000 in Azam, 2006). The expansion <strong>of</strong> the city is occurring both horizontally <strong>and</strong> vertically<br />

due to the development <strong>of</strong> formal <strong>and</strong> informal housing settlements.<br />

1.4.3 Selection <strong>of</strong> housing blocks for detail studies<br />

Since the study is related to the physical densities, spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements<br />

<strong>and</strong> urban sprawl, both the formal <strong>and</strong> informal housing blocks have been identified,<br />

classified <strong>and</strong> discussed to compare their variables <strong>of</strong> FAR, percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by<br />

buildings; usability <strong>of</strong> space, availability <strong>of</strong> cross ventilation <strong>and</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> daylight inside<br />

the block.<br />

.<br />

Figure 1.1: Procedure <strong>of</strong> block selection (Google Earth, 2007)<br />

4

Since the study is dealing with the physical densities, spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing settlements<br />

<strong>and</strong> urban sprawl, in order to do study at lower level scale, ‘urban blocks’ have been<br />

considered as the major units <strong>of</strong> analysis. Despite that house on plot is not sufficient to<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> urban sprawl because communal open spaces <strong>and</strong> streets need to be considered to<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> the phenomenon <strong>of</strong> urban sprawl. The urban blocks have been studied to consider<br />

such communal open spaces <strong>and</strong> surrounding roads. Analysis <strong>of</strong> the city in district level is<br />

relevant but not practical. Figure 1.1 is showing the selection <strong>of</strong> block from urban housing<br />

settlements. The following criteria were taken into consideration to select the blocks <strong>of</strong><br />

formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements: First, the variations <strong>of</strong> blocks, in terms <strong>of</strong> FAR were taken<br />

into consideration for the selection <strong>of</strong> formal housing blocks. Secondly, the location, age <strong>and</strong><br />

house form <strong>of</strong> the informal settlements were considered as the criteria because physical<br />

densities <strong>of</strong> the informal settlements depend on the age <strong>and</strong> location <strong>of</strong> the settlement. House<br />

forms have been considered as a factor to classify informal settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city. The<br />

approach used to select urban blocks for detailed studies was by identifying which is enough<br />

to facilitate the comprehension <strong>of</strong> key study variables namely: FAR value, percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong><br />

coverage by buildings, space usability, cross ventilation <strong>and</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> daylight inside the<br />

block.<br />

Fig 1.2: Location <strong>of</strong> case areas<br />

In relation to those criteria blocks from Road number 3 at Dhanmondi residential area,<br />

Shobhanbagh government <strong>of</strong>ficers’ colony, Banani Model Town, Baridhara diplomatic zone,<br />

newly planned Defense Officers’ Housing Society (DOHS) in Baridhara, Mirpur 10 number<br />

5

esidential area have been selected as formal housing settlements (Fig 1.2). Among them<br />

Dhanmondi is the first planned residential area <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city for the high income people<br />

which has been planned in 1954. Shobhanbagh <strong>of</strong>ficers’ colony is developed for the first<br />

class government <strong>of</strong>ficers. Banani <strong>and</strong> Baridhara are the area for high income <strong>and</strong> aristocrat<br />

people which also have been planned in 1964. DOHS is the newly planned housing for the<br />

retired defense <strong>of</strong>ficers. Mirpur 10 number is the area for middle <strong>and</strong> lower middle income<br />

people has been developed in mid 1960. ‘Geneva Camp’ <strong>and</strong> ‘Tikkapara Bustee’ in<br />

Mohammadpur have been selected as informal housing settlements. ‘Bustee’ is the local<br />

name <strong>of</strong> informal settlements in Bangladesh. Two informal settlements have been selected in<br />

the present study as cases because the type <strong>and</strong> physical characteristics <strong>of</strong> the most informal<br />

settlements are similar. Two types <strong>of</strong> informal settlements can be seen in <strong>Dhaka</strong>. The houses<br />

in one type are made by brick walls. Despite that, most <strong>of</strong> the informal settlements are<br />

constructed by earth materials. The houses in ‘Geneva Camp’ are made by brick walls <strong>and</strong><br />

tin’s ro<strong>of</strong> where as in ‘Tikkapara Bustee’ are made by earth materials.<br />

Selection <strong>of</strong> Informal settlements<br />

Geneva Camp in Mohammadpur<br />

This settlement is situated in the Mohammadpur thana. This thana is a residential area for<br />

middle income people with some minor commercial activities. The Geneva camp has been<br />

developed in the center <strong>of</strong> this thana. Thana, which means police station, is the third level <strong>of</strong><br />

administrative boundary in Bangladesh. This settlement has been selected for the study due to<br />

its old age, location <strong>and</strong> house forms. Most <strong>of</strong> the informal settlements in the <strong>Dhaka</strong> city are<br />

made by earth materials but few <strong>of</strong> them are made by brick wall with tin’s ro<strong>of</strong>. The houses<br />

in ‘Geneva camp’ are made by the brick wall with tin’s ro<strong>of</strong>. This settlement looks like<br />

planned housing area but the provision <strong>of</strong> infrastructure <strong>and</strong> other facilities are not available.<br />

Tikkapara Bustee in Mohammadpur<br />

Tikka Para Bustee has been selected due to its age, location <strong>and</strong> house forms. The physical<br />

characteristics <strong>and</strong> house forms <strong>of</strong> this settlement are similar to most <strong>of</strong> the informal<br />

settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city (author’s previous observation). This settlement is located in the<br />

periphery <strong>of</strong> the city where the houses are made by earth materials. The analysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> this settlement will provide idea about most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

informal settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong> city.<br />

Selection method <strong>of</strong> Formal settlements<br />

Road number 3 at Dhanmondi residential area<br />

Dhanmondi is the first planned residential area <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city. This area was developed as a<br />

residential area for high income people in 1954 during Pakistan period. But now it is treated<br />

as an area <strong>of</strong> mix function. A lot <strong>of</strong> high, medium <strong>and</strong> low rise housing settlements have<br />

developed in this area for its mix functionality. Road number 3 is the residential area with<br />

some commercial activities.<br />

Shobhanbagh <strong>of</strong>ficers’ colony<br />

Shobhanbagh <strong>of</strong>ficers’ colony at Shobhanbagh has been developed for the first class<br />

government <strong>of</strong>ficers’ <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh. Most <strong>of</strong> the government housing blocks in <strong>Dhaka</strong> are<br />

like this block where the percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings is very low. There are 16<br />

buildings in this block.<br />

6

Banani Model Town residential area<br />

This area was developed in 1964 during Pakistan period for high income people. The density<br />

is low in terms <strong>of</strong> FAR <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings. There are 8 buildings<br />

in this block.<br />

Baridhara diplomatic zone<br />

Baridhara is situated in the Gulshan thana. It was planned in 1962 during Pakistan period but<br />

the Bangladesh government has developed this area in 1972 as a residential area. It is the<br />

posh area <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city for the rich <strong>and</strong> aristocrat people. The area is considered due to its<br />

low percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings <strong>and</strong> low FAR value.<br />

Newly planned Baridhara Defense Officer’s Housing Society (DOHS)<br />

This area has been developed to provide housing to the retired defense <strong>of</strong>ficers. The houses in<br />

this block are very close to one another. Percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings <strong>and</strong> FAR<br />

value are very high. This block is comprised <strong>of</strong> 14 buildings.<br />

Mirpur 10 number circle residential area<br />

This are is located in the Mirpur thana. It was planned in the mid <strong>of</strong> 1960s during Pakistan<br />

period for the Muslims who came from India after separation <strong>of</strong> India <strong>and</strong> Pakistan from<br />

British in 1947.This area has been selected due to its low FAR value <strong>and</strong> very high<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings.<br />

1.4.3 Data collection methods<br />

In this study both quantitative <strong>and</strong> qualitative methods have been applied. The quantitative<br />

methods comprise <strong>of</strong> measurements, analysis <strong>of</strong> documents, empirical studies, maps <strong>and</strong><br />

aerial photographs, previous observations as well as discussions. On the other h<strong>and</strong> the<br />

qualitative sources comprise <strong>of</strong> theoretical literatures, analysis <strong>of</strong> documents <strong>and</strong> previous<br />

observation. The data collection methods have been conducted in two phases. First, the<br />

classification <strong>and</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> physical densities in terms <strong>of</strong> FAR <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong><br />

coverage by buildings for both formal <strong>and</strong> informal housing settlements have been carried<br />

out. In this phase measurements <strong>of</strong> whole block area, individual plot area, covered l<strong>and</strong> by<br />

buildings <strong>and</strong> number <strong>of</strong> storeys <strong>of</strong> buildings have been carried out to calculate the physical<br />

densities. The identification, usability <strong>and</strong> classification <strong>of</strong> spaces have also been carried out<br />

in the same phase. After that the observation <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial documents regarding that study<br />

areas are analyzed to explore the background information <strong>and</strong> the spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> the<br />

settlements.<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> photographs<br />

After formulating problem <strong>and</strong> fixing the study area, the author appointed his university<br />

classmates <strong>and</strong> friends in Bangladesh to take the photographs <strong>of</strong> the study area about the<br />

formulated problem. The photographers have taken photographs according to the suggestion<br />

<strong>of</strong> the author <strong>of</strong> this study. It was required to take photographs <strong>of</strong> typical, critical, good<br />

qualities <strong>and</strong> difficult situation. The space usability, cross ventilation <strong>and</strong> provision <strong>of</strong><br />

daylight inside the informal housing blocks have been explored from the photographs.<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> plans <strong>and</strong> maps<br />

Plans <strong>and</strong> drawings provide information to analyse the physical extension <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong> city as<br />

well as FAR values, setbacks, original layout <strong>of</strong> plots <strong>and</strong> size <strong>of</strong> plots in the study area.<br />

Original <strong>and</strong> existing plans <strong>of</strong> the study areas are gathered from several secondary sources,<br />

for instance previous studies or <strong>of</strong>ficial websites <strong>of</strong> several relevant organizations. Then the<br />

7

existing <strong>and</strong> previous maps are compared to explore the changes <strong>of</strong> FAR values, percentage<br />

<strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings, setbacks <strong>and</strong> layout <strong>of</strong> plots, <strong>and</strong> space usability.<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> Aerial photograph<br />

Aerial photographs are the main source to calculate the block size, l<strong>and</strong> coverage by<br />

buildings, plot sizes, number <strong>of</strong> storeys <strong>of</strong> building, setback <strong>and</strong> open spaces. The aerial<br />

photographs are collected by the ‘Google Earth’. The dimensions are measured by using the<br />

‘ruler’ tools <strong>of</strong> the ‘Google Earth’. The measurement procedures are described as follows:<br />

Measurements<br />

The dimensions <strong>of</strong> plot, l<strong>and</strong> covered by building, total block area, area <strong>of</strong> open space,<br />

setback <strong>and</strong> number <strong>of</strong> storeys are measured to calculate the physical densities. All<br />

dimensions are collected from the aerial photographs which are available in the ‘Google<br />

Earth’. The dimensions are measured by using ‘Google Earth’ tool which is called ‘ruler’.<br />

The measurements <strong>of</strong> physical densities in terms <strong>of</strong> FAR, percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by<br />

buildings <strong>and</strong> open space are conducted at block level.<br />

Applied procedure to measure the height <strong>of</strong> building: The building heights are measured to<br />

calculate the number <strong>of</strong> floors. Numbers <strong>of</strong> floors are required to calculate the total floor area<br />

which means the area <strong>of</strong> ground floor including its wall thickness multiplied by its number <strong>of</strong><br />

storeys. The building height is calculated from the shadow <strong>of</strong> building which is available in<br />

the aerial photograph <strong>of</strong> Google earth. The author has also suggested his appointed friends to<br />

visit the selected area to get data about the number <strong>of</strong> floors <strong>of</strong> the buildings. Then collected<br />

<strong>and</strong> measured data has compared each other to reduce error. According to the Bangladesh<br />

National Building Code (BNBC, 1993), the height <strong>of</strong> each floor should be minimum 3<br />

meters.<br />

Figure 1.3 shows procedure to measure the height <strong>of</strong> buildings. In this figure the shadow<br />

length is 15 meters which has been calculated from the aerial picture provided by the ‘Google<br />

Earth’. So it can be assumed that the building is 5 storeys because the height <strong>of</strong> each building<br />

is approximately 3 meters.<br />

Figure 1.3: The diagrammatic presentation <strong>of</strong> the height calculation (Google<br />

Earth, 2007 <strong>and</strong> adapted for this current study)<br />

8

Applied Procedure to calculate l<strong>and</strong> coverage: In this study L<strong>and</strong> coverage means the<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> covered by buildings available in the selected block <strong>and</strong> total l<strong>and</strong> covered<br />

by block. The total l<strong>and</strong> covered by the block is calculated with the half <strong>of</strong> its surrounding<br />

road width. Figure 1.4 is showing the procedure <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage calculation.<br />

Figure 1.4: Procedure <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage calculation<br />

In the figure 1.4<br />

BW = Block width with half <strong>of</strong> the surrounding road width, BL = Block length with half <strong>of</strong><br />

the surrounding road width <strong>and</strong> Block area (BA) = BL x BW.<br />

If the total built up area inside the block = A1 (Addition <strong>of</strong> the ground floor area <strong>of</strong> all<br />

buildings inside the block), the percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by built up area= (A1/BA) x 100<br />

Applied Procedure to calculate floor area ratio (FAR): The FAR indicates the ratio <strong>of</strong> built<br />

area <strong>and</strong> total l<strong>and</strong> covered by the block. The area <strong>of</strong> total l<strong>and</strong> coverage by the block<br />

Figure 1.5: Calculation <strong>of</strong> the floor area occupied by individual building<br />

9

indicates the area <strong>of</strong> block including half <strong>of</strong> its surrounding road width. The built area means<br />

the total floor area <strong>of</strong> all buildings which is based on the actual floor area including wall<br />

thickness <strong>of</strong> each structure, <strong>and</strong> multiplied by the number <strong>of</strong> floors. Figure 1.5 is showing the<br />

calculation <strong>of</strong> the total floor area <strong>of</strong> a building. The total floor area inside the block will be<br />

the addition <strong>of</strong> the total floor area <strong>of</strong> all buildings inside the block.<br />

In the figure 1.5<br />

Floor Area, A = L X W unit square<br />

So, Total Floor Area occupied by this building, A1 = A X 5 unit square (Since the building is<br />

5 storeys)<br />

If the total floor area <strong>of</strong> all buildings inside the block = A2 (Addition <strong>of</strong> the total floor area <strong>of</strong><br />

all buildings inside the block) then Floor Area Ratio (FAR) = A2/BA<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial documents<br />

Previous study reports or evaluation <strong>of</strong> the same study area, administrative documents, news<br />

paper clipping, other articles appearing in the mass media have been collected from the<br />

internet or other secondary sources. The change <strong>of</strong> spatial patterns <strong>and</strong> growth due to develop<br />

informal settlements have been analysed from the <strong>of</strong>ficial documents.<br />

1.4.4 Summary <strong>of</strong> the study issues <strong>and</strong> used methods<br />

The present study has followed several methods to analyze <strong>and</strong> investigate different relevant<br />

issues <strong>of</strong> the study. Figure 1.6 shows the used methods for gathering idea about the several<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> study.<br />

Aspects<br />

<strong>Sprawl</strong><br />

theory<br />

Concept<br />

<strong>of</strong> block<br />

types<br />

Back<br />

ground <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Dhaka</strong><br />

Methods<br />

Theory<br />

analysis<br />

Y Y<br />

Empirical<br />

studies<br />

Y Y Y<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

aerial<br />

photographs<br />

Y Y Y<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

photographs<br />

Y Y Y<br />

Own<br />

observations<br />

Y Y<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

plans <strong>and</strong><br />

maps<br />

Y<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

documents<br />

Y<br />

Figure 1.6: Summary <strong>of</strong> study aspects <strong>and</strong> methods<br />

Here Y means that method <strong>and</strong> corresponding aspect have been used in this study.<br />

10<br />

<strong>Density</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> the blocks <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Dhaka</strong><br />

Spatial qualities<br />

<strong>of</strong> the blocks <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Dhaka</strong>

CHAPTER 2<br />

THEORY OF THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK<br />

The purpose <strong>of</strong> this chapter is to present the theoretical <strong>and</strong> conceptual frame work that is<br />

considered <strong>and</strong> reflected upon, <strong>and</strong> which will guide this study. The focus is on the concepts<br />

that centre on analysis <strong>of</strong> physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing blocks, urban<br />

sprawl, <strong>and</strong> informal settlements. The concepts employed are discussed in relation with the<br />

theories. It is necessary to identify relevant variables that can be used in the analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> housing blocks, since the objectives <strong>of</strong> the study is<br />

to analyze physical densities <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities <strong>of</strong> urban housing block.<br />

2.1 <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Sprawl</strong><br />

<strong>Urban</strong> sprawl is one <strong>of</strong> the contemporary issues <strong>of</strong> today’s world. It is very difficult to find a<br />

common definition to urban sprawl. But the most common phenomenon <strong>of</strong> urban sprawl is<br />

expansion <strong>of</strong> urban area without efficient use <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong>. According to Vestbro<br />

“<strong>Urban</strong> sprawl may be defined as the phenomenon when urban areas exp<strong>and</strong><br />

without procedures for efficient l<strong>and</strong> use. It is typically expressed in allocating<br />

ample space to roads <strong>and</strong> parking areas, to buffer zones <strong>and</strong> impediments<br />

(leftover spaces) between built-up areas, <strong>and</strong> in residential developments with low<br />

densities. Such planning procedures lead to encroachment <strong>of</strong> valuable<br />

agricultural l<strong>and</strong>, to long travel distances between residences <strong>and</strong> work places, to<br />

high infrastructural costs because <strong>of</strong> long lines <strong>of</strong> roads, pipes, drainage ditches<br />

etc per house, <strong>and</strong> to a lack <strong>of</strong> urban qualities. Combined with the construction <strong>of</strong><br />

external shopping malls urban sprawl also leads to the deterioration <strong>of</strong> local<br />

services <strong>and</strong> to segregation between those who have cars <strong>and</strong> those who don’t”<br />

(Vestbro, 2004).<br />

In the city with sprawl, the residential area is developed with low physical densities. As a<br />

result there is an encroachment <strong>of</strong> development to the valuable agricultural l<strong>and</strong> or other open<br />

spaces. The area <strong>of</strong> the city increases horizontally for that encroachment. The cost <strong>of</strong><br />

infrastructures <strong>and</strong> traveling increase due to the development <strong>of</strong> long lines <strong>of</strong> roads, pipes,<br />

drainage etc, <strong>and</strong> so, there is a close relationship between low density residential<br />

development <strong>and</strong> urban sprawl. This present study will try to explore that relationship by<br />

analyzing the housing densities <strong>of</strong> <strong>Dhaka</strong>.<br />

According to Galster, et. el. (2001) “sprawl can be observed in different circumstances <strong>and</strong><br />

conditions; it is possible that there can be different types <strong>of</strong> sprawl, which consist <strong>of</strong><br />

combinations <strong>of</strong> different variables”. They propose different dimensions <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong><br />

when those low values are found in an area, then it signifies urban sprawl environments.<br />

<strong>Density</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> the vital dimensions among them. In spite <strong>of</strong> the mixed l<strong>and</strong> use<br />

characteristics with medium or high physical density in terms <strong>of</strong> FAR <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong><br />

coverage, the problems regarding to sprawl can be seen in a lot <strong>of</strong> cities all over the world<br />

due to the development <strong>of</strong> low dense informal housing blocks in the centre or periphery <strong>of</strong> the<br />

city. The physical density has been calculated from the FAR <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> covered<br />

by buildings in the specific block which has been described in detail in the previous chapter.<br />

Downs (1999) notes several causes <strong>of</strong> urban sprawl. Unlimited outward extensions <strong>of</strong><br />

development as well as low-density residential <strong>and</strong> commercial settlements are the prime<br />

causes among them. This writer also notes some effects <strong>of</strong> sprawl which comprise <strong>of</strong> air<br />

11

pollution, extensive use <strong>of</strong> energy for movement <strong>and</strong> inability to provide adequate<br />

infrastructure to the citizens.<br />

The definition <strong>of</strong> urban sprawl, its causes <strong>and</strong> effects in relation to the density issues <strong>of</strong> urban<br />

area are analyzed for different formal <strong>and</strong> informal housing blocks <strong>of</strong> the case city. However,<br />

the informal housing blocks <strong>and</strong> its physical density are analyzed in detail. In this study the<br />

negative <strong>and</strong> positive impacts <strong>of</strong> physical density on urban sprawl are being explored.<br />

2.2 <strong>Physical</strong> density<br />

<strong>Density</strong> can be defined from two perspectives, namely population density <strong>and</strong> physical<br />

density. Considering the need to address the problems associated with urban sprawl, it is<br />

important to analyze the physical density. Regarding the efficiency <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> uses, the cost<br />

effectiveness <strong>of</strong> infrastructure has a direct relationship to the intensity <strong>of</strong> physical density <strong>and</strong><br />

thus to urban sprawl. According to Acioly <strong>and</strong> Davidson, “the size <strong>of</strong> plot, the amount <strong>of</strong> plot<br />

which can be built up (plot coverage) <strong>and</strong> the height <strong>of</strong> the building (floor space index or<br />

Floor Area Ratio) give the dimensions <strong>of</strong> the most visible aspect <strong>of</strong> density: the amount <strong>of</strong><br />

space which is built”. (Acioly <strong>and</strong> Davidson,1996:7).<br />

There are some advantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages <strong>of</strong> high <strong>and</strong> low density. Acioly <strong>and</strong> Davidson<br />

Figure 2.1: Advantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages <strong>of</strong> high versus low density, Issues that are<br />

relevant to this study are enclosed in the circle. Source: Acioly <strong>and</strong> Davidson, 1996:7.<br />

again note the advantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages <strong>of</strong> high <strong>and</strong> low density (Acioly <strong>and</strong> Davidson,<br />

1996:6) as seen below. They argue that high density assures the maximization <strong>of</strong> public<br />

investments including infrastructure, services <strong>and</strong> transportation, <strong>and</strong> allows efficient<br />

utilization <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong>. They also argue that high density settlement schemes can overload<br />

infrastructure <strong>and</strong> services <strong>and</strong> put extra pressure on l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> residential spaces, producing<br />

12

crowded <strong>and</strong> unsuitable environments for human development. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, low<br />

densities may increase per capita cost <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong>; infrastructure <strong>and</strong> services, affecting the<br />

sustainability <strong>of</strong> human settlements, <strong>and</strong> producing urban environment that constrain social<br />

interactions. Those advantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages are summarized in figure 2.1.<br />

The formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements in <strong>Dhaka</strong>, where densities are very high with narrow<br />

roads <strong>and</strong> no or little open space <strong>and</strong> in most cases no areas for common amenities, it is<br />

required that developments which contribute to efficient l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> efficient infrastructure<br />

provision should be adopted. The present study focuses on the two advantages <strong>of</strong> high density<br />

which are enclosed in the circle (Figure 2.1) that are assumed to be the biggest problem in the<br />

housing block, especially in the housing block <strong>of</strong> informal settlements.<br />

The advantages <strong>and</strong> problems related to the high <strong>and</strong> low density have been considered to<br />

explore the advantages <strong>and</strong> problems <strong>of</strong> existing FAR <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage as<br />

well as to determine the functionality <strong>of</strong> space in spite <strong>of</strong> the high density inside the block.<br />

Acioly <strong>and</strong> Davidson (1996) point out that there are many factors those influence density,<br />

some <strong>of</strong> them which can be dealt with directly, some indirectly <strong>and</strong> others over which there is<br />

very little possible action. Figure 2.2 summarizes some <strong>of</strong> the most important factors which<br />

influence the density.<br />

Figure 2.2: Influences on density. Box: focus in this study. Source: Acioly<br />

<strong>and</strong> Davidson, 1996:7<br />

There are a lot <strong>of</strong> factors which influence density but the present study will focus on the three<br />

issues in the rectangles in Fig. 2.2. In this study the following questions are being explored:<br />

what are the prevailing densities for block in formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements? Which<br />

physical densities in formal <strong>and</strong> informal settlements could be considered dense for optimal<br />

utilisation <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> infrastructure? How do high densities affect spatial qualities such as<br />

cross ventilation <strong>and</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> sunlight in side the houses?<br />

13

2.2.1 Measurement <strong>of</strong> physical densities<br />

According to Rådberg the parameters that can be used to measure urban density are<br />

residential density, building height <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> built up area (Rådberg, 1996:390).The<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> built up area means the percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by buildings. The<br />

residential density which means FAR <strong>and</strong> the percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by building are<br />

considered in this study to measure the physical densities.<br />

FAR is the ratio between total floor area by number <strong>of</strong> floors <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong> area. The total<br />

floor area means the area <strong>of</strong> total floors <strong>of</strong> all the buildings available in the block. The l<strong>and</strong><br />

area includes the total l<strong>and</strong> area covered by block including half <strong>of</strong> its surrounding roads<br />

width <strong>and</strong> communal open space. The inclusion <strong>of</strong> half the street <strong>and</strong> communal spaces at<br />

block level is important since those factors contribute to urban sprawl.<br />

FAR =<br />

Total floor area (area <strong>of</strong> all floors <strong>of</strong> all buildings)<br />

Total l<strong>and</strong> area occupied by block<br />

Percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage is the percentage <strong>of</strong> total l<strong>and</strong> covered by buildings inside the<br />

block <strong>and</strong> the total l<strong>and</strong> area <strong>of</strong> block with the half <strong>of</strong> its surrounding roads.<br />

Percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage =<br />

Total l<strong>and</strong> covered by buildings inside the block<br />

Total l<strong>and</strong> area occupied by block<br />

Figure 2.3 is showing the concept <strong>of</strong> a floor area ratio <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage for an<br />

Figure: 2.3: Conceptual model <strong>of</strong> FAR values <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage. Source:<br />

Gren, 2006:18.<br />

individual building. The present study deals with the FAR <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage <strong>of</strong><br />

urban housing blocks. The total floor area <strong>of</strong> the block would be calculated by adding the<br />

floor area <strong>of</strong> individual building. Figure 2.3 shows the number <strong>of</strong> floors <strong>and</strong> respective FAR<br />

value. The first three values can be considered as a realistic value <strong>of</strong> FAR. The last three are<br />

14

unrealistic because tall buildings need to be placed at longer distance which means the<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage should be less.<br />

Rådberg has analysed the density in urban blocks in Sweden; four out <strong>of</strong> 25 has been<br />

illustrated in figure 2.4. The values presented in the figure 2.4 are estimated ranges, which<br />

aim to visualize the way in which different building types occupy l<strong>and</strong> in relation to the FAR<br />

values. He estimated that the FAR value for 1 storey villas range from 0.10 to 0.15 with 5-<br />

10% l<strong>and</strong> coverage whereas 8 storey tower blocks have FAR value <strong>of</strong> 0.95 with 10-15% l<strong>and</strong><br />

coverage. These analyses can be used to analyze the physical densities <strong>of</strong> any urban block.<br />

1 storey villas<br />

FAR = 0.1– 0.15<br />

Coverage 5-10%<br />

3 storey lamella blocks<br />

FAR = 0.55<br />

Coverage 15 – 20%<br />

8 storey tower block<br />

FAR = 0.95<br />

Coverage = 10 -15%<br />

The analysis <strong>of</strong> densities can explore the comparison <strong>of</strong> FAR, space use <strong>and</strong> spatial qualities,<br />

as well as dimensions <strong>of</strong> urban sprawl. Rådberg developed a systematic method to analyze<br />

the densities <strong>of</strong> housing block for Swedish urban block (Figure 2.5). The analyses <strong>of</strong> FAR,<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> coverage by building <strong>and</strong> number <strong>of</strong> storeys can be seen in figure 2.5.<br />

Figure 2.5 shows the classification <strong>of</strong> urban blocks in the Swedish context. Rådberg (1996) is<br />

<strong>of</strong> the view that for the classification <strong>of</strong> typologies, a typo-morphological urban analysis (as<br />

opposed to the functional typology) <strong>of</strong> urban types should be made which means buildings<br />

are studied in context, together with the surrounding public <strong>and</strong> private spaces. He argues that<br />

the analysis <strong>of</strong> such object may be a group <strong>of</strong> buildings <strong>and</strong> open spaces which mean urban<br />

block, the building lots or the street pattern.<br />

Rådberg uses the parameters <strong>of</strong> residential density, building height <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>and</strong><br />

covered by buildings. He suggests that the basic methodology for typological classification<br />

should be essentially the same regardless <strong>of</strong> the country (Rådberg, 1996:386).<br />

Figure 2.5 is showing the parameters to classify the urban types. Here the residential density<br />

‘e’, building height or average number <strong>of</strong> storeys is ‘n’ <strong>and</strong> the percentage <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> covered by<br />

building is ‘v ’. The formula is e = v x n.<br />

Rådberg shows that if the number <strong>of</strong> different urban blocks are registered <strong>and</strong> place each<br />

block as a dot on the graph (according to their urban density <strong>and</strong> number <strong>of</strong> storeys), the<br />

individual observations <strong>of</strong> blocks (dot in the diagram) tend to cluster into a larger bubble<br />

15<br />

19th century inner city<br />

FAR = 1.5 – 2.2<br />

Coverage = 40%<br />

Figure 2.4: <strong>Density</strong> <strong>of</strong> several urban blocks in Sweden. Source: Rådberg, 1988 in<br />

Gren, 2006: 18.

Fig 2.5: <strong>Urban</strong> density, building height <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> built-up area for eight urban<br />

types. 1) High density inner city blocks, 4-6 storeys, 2) Blocks with planted inner<br />

courtyards, 4-6 storeys, 3) High rise developments, point blocks or slab blocks 8-12<br />

storeys 4) 3-4 storeys “walk-ups” (lamellas), 5) Pre industrial low rise traditional blocks,<br />

6) Garden suburbs, mixed developments, 7) Small one-family houses (bungalows) on<br />

small individual plots, 8) Villas on larger plots. Source: Rådberg, 1996: 391.<br />

(Rådberg, 1998). For instance, figure 2.5 shows the villas as type 8 is low dense residential<br />

densities which are less than 0.1. Applying this methodology in the analysis <strong>of</strong> this study may<br />