dr. ronald e. mcnair acknowledgements - University of St. Thomas

dr. ronald e. mcnair acknowledgements - University of St. Thomas

dr. ronald e. mcnair acknowledgements - University of St. Thomas

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

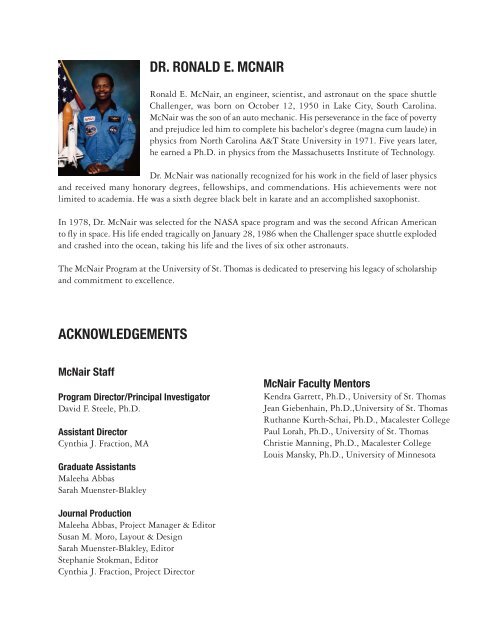

DR. RONALD E. MCNAIR<br />

Ronald E. McNair, an engineer, scientist, and astronaut on the space shuttle<br />

Challenger, was born on October 12, 1950 in Lake City, South Carolina.<br />

McNair was the son <strong>of</strong> an auto mechanic. His perseverance in the face <strong>of</strong> poverty<br />

and prejudice led him to complete his bachelor’s degree (magna cum laude) in<br />

physics from North Carolina A&T <strong>St</strong>ate <strong>University</strong> in 1971. Five years later,<br />

he earned a Ph.D. in physics from the Massachusetts Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology.<br />

Dr. McNair was nationally recognized for his work in the field <strong>of</strong> laser physics<br />

and received many honorary degrees, fellowships, and commendations. His achievements were not<br />

limited to academia. He was a sixth degree black belt in karate and an accomplished saxophonist.<br />

In 1978, Dr. McNair was selected for the NASA space program and was the second African American<br />

to fly in space. His life ended tragically on January 28, 1986 when the Challenger space shuttle exploded<br />

and crashed into the ocean, taking his life and the lives <strong>of</strong> six other astronauts.<br />

The McNair Program at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Thomas</strong> is dedicated to preserving his legacy <strong>of</strong> scholarship<br />

and commitment to excellence.<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

McNair <strong>St</strong>aff<br />

Program Director/Principal Investigator<br />

David F. <strong>St</strong>eele, Ph.D.<br />

Assistant Director<br />

Cynthia J. Fraction, MA<br />

Graduate Assistants<br />

Maleeha Abbas<br />

Sarah Muenster-Blakley<br />

Journal Production<br />

Maleeha Abbas, Project Manager & Editor<br />

Susan M. Moro, Layout & Design<br />

Sarah Muenster-Blakley, Editor<br />

<strong>St</strong>ephanie <strong>St</strong>okman, Editor<br />

Cynthia J. Fraction, Project Director<br />

McNair Faculty Mentors<br />

Ken<strong>dr</strong>a Garrett, Ph.D., <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Thomas</strong><br />

Jean Giebenhain, Ph.D.,<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Thomas</strong><br />

Ruthanne Kurth-Schai, Ph.D., Macalester College<br />

Paul Lorah, Ph.D., <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Thomas</strong><br />

Christie Manning, Ph.D., Macalester College<br />

Louis Mansky, Ph.D., <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Minnesota

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

DO I MATTER, OR AM I JUST A NAME ON A CHART?<br />

CANCER PATIENTS’ EXPERIENCES WITH HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1<br />

Oluwademilade Adediran ’13<br />

ENHANCING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION FOR LOW-INCOME CHILDREN:<br />

EXPLORING POSSIBILITIES FOR INCORPORATING MONTESSORI METHODS<br />

WITHIN THE HEAD START PROGRAM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19<br />

Kesha Berg ’13<br />

EXPLORING THE INFLUENCE OF HIV-1 RESISTANT CONFERRING MUTATIONS<br />

ON ANTIRETROVIRAL DRUG RESISTANCE IN HIV-2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41<br />

Mon<strong>dr</strong>aya Howard ’13<br />

WASTE(LESS): A PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACH TOWARD REDUCING FOOD WASTE . . . . . . . . 47<br />

Bridgette Kelly ’12<br />

HEALTH CARE ACCESSIBILITY IN THE TWIN CITIES METROPOLITAN AREA<br />

HMONG COMMUNITY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61<br />

Chia Lee ’13<br />

A QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF TEACHERS’ PERCEPTION TOWARDS HMONG<br />

AMERICAN STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT IN MINNESOTA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72<br />

Mai-Eng Lee ’12

ABSTRACT<br />

The purpose <strong>of</strong> the present study is to explore what female musicians, who were 1-5 years<br />

post-treatment for breast cancer, had to say about their experience <strong>of</strong> mattering within<br />

the context <strong>of</strong> their health care. According to Tucker, Dixon and Griddine (2010),<br />

mattering is defined as “the experience <strong>of</strong> moving through life being noticed by and<br />

feeling special to others who also matter to us” (p. 134). In 1890, William James<br />

reflected on mattering by saying “one <strong>of</strong> the worst injustices in the world would be to<br />

live life being unnoticed by others” (as cited in Tucker, Dixon & Griddine, 2010, p.<br />

135). Although the concept <strong>of</strong> mattering has been around for more than a hun<strong>dr</strong>ed<br />

years, it has only recently been studied more systematically. Research related to<br />

mattering has been applied to multiple subjects such as relationship fulfillment,<br />

education, and workplace satisfaction (Kawamura & Brown, 2008; Connolly, 2002;<br />

Tucker et al., 2010). The current study examines the experience <strong>of</strong> mattering within<br />

a health care context. Common themes identified from 38 interview transcripts indicated<br />

patients felt they did not matter when the doctors treated them as merely a cancer patient<br />

and a name on a chart. This meant the doctors did not collaborate with the patients<br />

and did not individualize their care. The results also state women disliked when they<br />

were given their diagnosis over the phone by nurses who did not have sufficient<br />

information. Patients felt they mattered when physicians seemed to care about their<br />

livelihood. When doctors explained treatment options allowing for patient input, the<br />

patient felt they mattered. Patients reported extreme approval <strong>of</strong> their doctors when they<br />

received something such as a call from them to see how they were coping with treatments.<br />

Further research with doctors is needed in order to understand how health care pr<strong>of</strong>essions<br />

perceive patients.<br />

In the 19 th Century the father <strong>of</strong> modern psychology, William James, stated<br />

“one <strong>of</strong> the worst injustices in the world would be to live life being unnoticed<br />

by others” (as cited in Tucker, Dixon, & Griddine, 2010, p. 135). Mattering,<br />

as William James believed, is essential in order for an individual’s healthy<br />

development (Tucker et al., 2010). Mattering to others in our lives is the<br />

“experience <strong>of</strong> moving through life being noticed by and feeling special to<br />

others who also matter to us” (Tucker et al., 2010, p. 135). It can also be<br />

thought <strong>of</strong>, however, as a feeling that “we make a difference in the lives <strong>of</strong><br />

other people and that we are significant to the world around us” (France &<br />

Finney, 2009, p.104).<br />

Though the concept <strong>of</strong> mattering has been around since the 19th Century, it<br />

has only begun to be studied systematically in recent years, being applied to<br />

multiple subjects such as relationships, education, and workplace satisfaction.<br />

For example, it has been found that college students are more likely to stay at<br />

a particular college if they feel they matter to the institution (Tucker et al.,<br />

2010). In addition, workers are more satisfied with their place <strong>of</strong> employment<br />

if they feel like they matter to the company (Connolly, 2002). Kawamura and<br />

Brown (2008) examined relationship satisfaction by looking at division <strong>of</strong><br />

housework data collected from homemakers and exploring how much women<br />

perceived that they mattered to their husbands. The researchers measured how<br />

much the women reported the division <strong>of</strong> housework to be equal. What was<br />

DO I MATTER, OR AM I<br />

JUST A NAME ON A<br />

CHART? CANCER<br />

PATIENTS’<br />

EXPERIENCES WITH<br />

HEALTH CARE<br />

PROFESSIONALS<br />

Oluwademilade Adediran ’13<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Thomas</strong><br />

Mentor<br />

Jean Giebenhain, Ph.D.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Psychology<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Thomas</strong><br />

1

UST McNair Scholars Program Research Journal<br />

interesting about this study was the more wives reported<br />

they mattered to their husbands, the more likely they were<br />

to report the division <strong>of</strong> house work was equal, even if this<br />

was not the case. In other words, work equality depended<br />

upon how much the women felt they mattered to<br />

husbands.<br />

Mattering has also been shown to be a key factor in<br />

mental health and wellness among adolescents (Rayle,<br />

2005). A study conducted with high school students aimed<br />

to show the link between mattering to significant others,<br />

such as family, and the overall wellness <strong>of</strong> students. This<br />

study defined wellness in terms <strong>of</strong> physical, emotional, and<br />

psychological well-being. <strong>St</strong>udents felt they mattered to<br />

their families when they were assured they were significant,<br />

viewed as important, depended on by their families, and<br />

when their families were concerned with their fate and paid<br />

attention to them. It was found that females felt they<br />

mattered to their families more than males. Furthermore,<br />

it was also reported that mattering significantly predicted<br />

wellness for females. In other words, when females scored<br />

high for mattering, they also scored high in wellness.<br />

Though studies have looked at a wide range <strong>of</strong> topics<br />

pertaining to mattering, little has been done in regards to<br />

mattering in a health care context as relating to lifethreatening<br />

diseases.<br />

Human beings are multi-cellular organisms composed<br />

<strong>of</strong> structural and functional units called cells. Cells grow<br />

and divide in a controlled way to produce more cells as they<br />

are needed to keep the body healthy. When cells become<br />

old or damaged, they die and are replaced with new cells.<br />

This work <strong>of</strong> art called the body, though complex and aweinspiring,<br />

is not perfect. There are several diseases which<br />

afflict the body without warning and threaten the life and<br />

livelihood <strong>of</strong> the host. Oftentimes, in the division <strong>of</strong> cells,<br />

something goes wrong and abnormal cells divide without<br />

control and are able to invade other tissues. The most<br />

common term for this abnormality is “cancer.” The<br />

National Cancer Institute reports that there are over a<br />

hun<strong>dr</strong>ed types <strong>of</strong> cancers, among which the most common<br />

to women is malignant neoplasms, or breast cancer.<br />

According to the National Cancer Institute, there were<br />

207,090 reported new cases <strong>of</strong> breast cancer in 2010 within<br />

the United <strong>St</strong>ates alone. Modern advancements in medicine<br />

have made it possible for more women to survive breast<br />

cancer than ever before (Salonen et al., 2011). Using the<br />

2<br />

latest data available, survival rates for those diagnosed with<br />

breast cancer are 89% after 5 years, 81% after 10 years, and<br />

73% after 15 years. This is a significant increase in survival<br />

rates compared to previous years (American Cancer Society,<br />

2010). These increased survival rates indicate the need for<br />

issues related to survivorship and long-term quality <strong>of</strong> life<br />

to be added to overall treatment considerations (Kaiser et<br />

al., 2009). If the patient matters, there could be a shift in<br />

efforts to not only wipe out the cancer cells but to try and<br />

preserve the livelihood <strong>of</strong> the patient after treatments are<br />

over. Livelihood in this case refers to the patient’s ability<br />

to return to their employment or the way in which they<br />

make their income. Medical advances allow doctors to<br />

provide more personalized care for their patients. During<br />

treatment, <strong>of</strong>tentimes doctors become focused in their<br />

work <strong>of</strong> eradicating the cancer cells they forget treatment,<br />

at least in some aspects, should be based on requirements<br />

defined by women with breast cancer (Landmark, bohler,<br />

Loberg, & Wahl, 2008). Research suggests the women are<br />

experts on their own lives and ideal doctors will listen to<br />

them and try to find ways to preserve their livelihood post<br />

treatment (Theisel, Schielein, & Splebl, 2010). The key<br />

topic to preserving the life and livelihood <strong>of</strong> a patient is<br />

whether or not the patient matters to the medical<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals as an individual.<br />

One such study that looked at the doctor-patient<br />

interaction as a part <strong>of</strong> mattering did so by studying<br />

interpersonal trust (Kaiser et al., 2009). The study looked<br />

at breast cancer patients’ trust in several <strong>of</strong> their health care<br />

providers. The study assessed breast cancer patients’ trust<br />

in regular providers, diagnosing physicians, and their<br />

cancer treatment team. In this study, patient trust was<br />

associated with patient satisfaction and treatment<br />

adherence. Findings suggest a trusting relationship with a<br />

regular provider facilitated higher satisfaction with other<br />

specialists (Kaiser et al., 2009). Though this study had<br />

important findings, it does not explain why patients were<br />

more likely to trust other specialists if they trusted their<br />

primary doctor. Mattering could be one <strong>of</strong> the key<br />

components <strong>of</strong> trust in a doctor-patient relationship. If a<br />

patient feels they matter to their primary doctors, they<br />

might trust them more. This trust could be carried over to<br />

other specialists the doctor recommends.<br />

Another qualitative study that assessed the relationship<br />

between patients and doctors was conducted with 13

Oluwademilade Adediran<br />

Psychology Mattering<br />

individuals dying <strong>of</strong> cancer (Janssen & MacLeod, 2010).<br />

Results indicated the patients felt they mattered to the<br />

doctors when treated as more than a cancer patient.<br />

Patients felt like more than just a cancer patient when<br />

doctors sought to find “common ground” with their patients.<br />

A common ground for the patients meant the doctors did<br />

not only inform patients they have an illness, but sat with<br />

them to answer any questions they might have. In some<br />

cases, the patients would encourage the doctor to be livelier<br />

by telling jokes. The patients remarked that this seemed<br />

to make doctors feel more comfortable and in return they<br />

seemed to be able to look past patients’ cancer to the<br />

patients’ lives. The doctors who made patients feel like they<br />

mattered were the ones who sat with the patients and<br />

listened for extended periods <strong>of</strong> time, without trying to<br />

rush <strong>of</strong>f to another patient. A woman from the study said,<br />

“Doctors should not just say this is a woman <strong>of</strong> 76 who’s got so<br />

and so, past history <strong>of</strong> such and such. You heal a whole person.<br />

We are not just a lump, an amorphous lump; we are body mind<br />

and soul” (Janssen & MacLeod, 2010, pg. 252). Doctors<br />

who were able to look into the patients lives were seen as<br />

caring and made patients feel they mattered. These two<br />

studies show ideal doctors are ones who valued or seemed<br />

to value the interactions with their patients. Good doctorpatient<br />

interactions are essential to the concept <strong>of</strong> mattering<br />

in a health care context.<br />

<strong>St</strong>udies investigating what patients perceive as the ideal<br />

doctor indicate patients want someone who is accessible,<br />

takes their time, is friendly and congenial, shows<br />

commitment and interest, is understanding and sensitive,<br />

and is responsive to the needs <strong>of</strong> patients (Theisel et al.,<br />

2010; O’Connor, 2011). Oftentimes, doctors lose sight <strong>of</strong><br />

the life and livelihood <strong>of</strong> the individual. Rarely do they<br />

take into account patient considerations about how they<br />

should be medically treated or what factors need to be<br />

considered in order to reduce the negative impact on their<br />

livelihood (Landmark et al., 2008). Part <strong>of</strong> mattering is<br />

looking to see how treatments will affect the individual.<br />

Do doctors take into account the patient’s life and<br />

livelihood when treating the individual? Are treatments<br />

specific to the individual or do doctors follow the same<br />

protocols for all patients? Dibbelt, Schaidhammer,<br />

Fleischer, and Greitemann, (2009) identify that the most<br />

important variable in mattering as related to health care is<br />

the ability for the doctor to let the patient decide what is<br />

next. This study emphasized the need for the doctor to be<br />

open to change and let the patients’ physical and emotional<br />

conditions, as well as communication, dictate what<br />

treatment should follow. In summary, when doctors sought<br />

to build a relationship with the patients that involved more<br />

than eradicating the cancer, the patients felt cared for, and<br />

ultimately reporting they felt as if they mattered to the<br />

doctor.<br />

The present study on mattering seeks to improve upon<br />

previous research in that it is conducted with a specific<br />

group in order to see what the patients had to say about<br />

their health care providers and identify factors <strong>of</strong><br />

specialized care that made breast cancer patients feel as if<br />

they mattered. This study is also unique in that it focuses<br />

on how doctors personalize care for patients. Uncovering<br />

whether or not breast cancer patients felt they mattered to<br />

their doctors is also an aim <strong>of</strong> this current research.<br />

Mattering, in the context <strong>of</strong> this research, refers to the<br />

“experience <strong>of</strong> moving through life being noticed by and<br />

feeling special to others who also matter to us” (Tucker et<br />

al., 2010, p. 135). Oftentimes it is not until a woman<br />

moves into survivorship that she realizes her body is no<br />

longer the same and her quality <strong>of</strong> life decreases (Salonen<br />

et al., 2011; Sanson-Fisher et al., 2010). This change in<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> life is problematic for musicians because <strong>of</strong> the<br />

direct impact it has on their careers.<br />

This current study is unique because it will use a special<br />

participant pool comprised <strong>of</strong> musicians. Being a musician<br />

constitutes a livelihood that hinges on the ability to play<br />

an instrument or sing at a specific pitch. Breast cancer<br />

treatments, including lumpectomies, lymph node removal,<br />

mastectomies, radiation, and chemotherapy, <strong>of</strong>ten damage<br />

physical functions such as lung capacity and upper body<br />

strength which can interfere with an artist’s ability to make<br />

music. Survivors can have long-term issues with pain,<br />

neuropathy, and lymphodema, not to mention chronic<br />

fatigue and a plethora <strong>of</strong> other side effects from treatments<br />

(Fisher et al., 2010). Using musicians for this study is<br />

critical because a condition such as lymphodema causes<br />

swelling <strong>of</strong> the arms. For a woman who does not have to<br />

use her arms at work, this might not be problematic.<br />

However, musicians who play string instruments use their<br />

arms for instrument support and sound production.<br />

Musicians were used for this study based on the direct<br />

affects cancer treatments can have on their livelihoods. In<br />

3

UST McNair Scholars Program Research Journal<br />

the case <strong>of</strong> musicians, if a woman is a singer or plays a wind<br />

instrument, lung scaring from radiation may diminish her<br />

lung capacity necessary to perform at the level she once did.<br />

Weaknesses as a result <strong>of</strong> lymph node removal, or injury<br />

from ports or <strong>dr</strong>ains, may make horn or violin players<br />

unable to hold their instruments for even short periods <strong>of</strong><br />

time.<br />

Most musicians train for a lifetime to perfect their craft.<br />

Music is <strong>of</strong>ten their way <strong>of</strong> life, and if treatments damage<br />

their way <strong>of</strong> life, it is incredibly difficult to find another<br />

means to make money and live. Medical specialists ought<br />

to understand the musician’s strong feelings toward her<br />

music. The patient should matter enough to doctors that<br />

they take their time to find other viable treatments that<br />

have less <strong>of</strong> an impact on the women’s ability to make<br />

music. The purpose <strong>of</strong> mattering in this study is to answer<br />

the question, if the patient matters to the doctor, and music<br />

matters to the patient, will the patient’s music matter to<br />

the doctor?<br />

The research goals for this project are tw<strong>of</strong>old. The first<br />

is to explore what female musicians who had cancer say<br />

about their experiences with their health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals,<br />

particularly if these women felt as though they mattered.<br />

In addition, it explores what behaviors from their doctors<br />

made them feel like they mattered and which ones made<br />

them feel like they didn’t matter. The second is to observe<br />

if health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals took into account the women’s<br />

livelihoods when prescribing treatments. (This research is<br />

part <strong>of</strong> an ongoing study to access female musicians’<br />

experiences with the health care system. This particular<br />

study uses the existing interview transcripts conducted by<br />

Drs. Jean Giebenhain and Sarah Schmalenberger, along<br />

with Charles Gessert, M.D. and Lisa <strong>St</strong>arr, CNP.) To<br />

achieve these goals, content analysis will be performed on<br />

the interview transcripts <strong>of</strong> thirty-eight female musicians<br />

who are one to five years post-treatment for breast cancer.<br />

METHODS<br />

I conducted content analysis (qualitative data analysis)<br />

on existing coded interview transcripts <strong>of</strong> 38 female<br />

musicians who were 1-5 years post-treatment for breast<br />

cancer. These interviews were originally conducted as part<br />

<strong>of</strong> an ongoing study by Drs. Giebenhain, Schmalenberger,<br />

4<br />

and Gessert, as well as Lisa <strong>St</strong>arr, CNP (For a fuller<br />

discussion <strong>of</strong> the participant pool and original methods see:<br />

Schmalenberger, Giebenhain, <strong>St</strong>arr, & Gessert, 2008). The<br />

interviews were analyzed for themes particularly related to<br />

mattering. The Nvivo 9 qualitative s<strong>of</strong>tware package was<br />

used to assist the analysis in order to identify themes<br />

associated with what women had to say about their<br />

experiences with health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. Analysis<br />

identified specific information related to behaviors health<br />

care providers exhibited that contributed to whether<br />

women felt as if they mattered or not.<br />

RESULTS<br />

NON-MATTERING BEHAVIORS<br />

After reviewing the coded transcripts, there were themes<br />

that emerged from the experiences <strong>of</strong> our participants.<br />

Themes related to mattering are identified below:<br />

Diagnosis delivered over the phone/<strong>St</strong>aff was not<br />

knowledgeable or helpful.<br />

There were several behaviors from healthcare<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals that made the women feel they didn’t matter.<br />

Patients experienced extreme dislike <strong>of</strong> their health care<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals when they were informed <strong>of</strong> their diagnosis<br />

over the phone. The women remarked the dislike came<br />

from the way the message was delivered. The nurse or<br />

technician who would make the call lacked compassion<br />

when giving the women their diagnosis. They would<br />

simply say the test results came in and the diagnosis is<br />

cancer. They would then tell the women to schedule<br />

surgery. In most instances when a diagnosis was delivered<br />

poorly, the women were not able to schedule treatment for<br />

weeks. Patients expressed extreme dislike <strong>of</strong> this system,<br />

saying it was cold and forced them to sit with the news <strong>of</strong><br />

their diagnosis for weeks without support. They also<br />

remarked that the nurses were not able to answer questions<br />

and lacked information that was critical to them. An<br />

example <strong>of</strong> these behaviors was encountered by a woman<br />

who was diagnosed over the phone. She said “The first bad<br />

thing about being told I had breast cancer was um, my doctor<br />

didn’t even tell me, it was like a nurse I didn’t even know just<br />

sort <strong>of</strong> called and said oh, um your result was positive and then,

Oluwademilade Adediran<br />

Psychology Mattering<br />

I don’t know anything else, bye, hung up.” The patient then<br />

called the nurse back to get some more explanation. She<br />

explained the situation by saying “I called back, the nurse<br />

goes, well we just got preliminary results, and we don’t know<br />

anything else. I said why didn’t the doctor call me? The nurse<br />

says oh well, it’s her day <strong>of</strong>f, so she couldn’t call you.” As the<br />

situation played out on the phone, the patient recalled<br />

being told, “Why don’t you call the hospital and try to find out<br />

something?” this patient was extremely dissatisfied with the<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> empathy exhibited by this hospital. The fact the<br />

doctor could not call herself was “jaw <strong>dr</strong>opping” to the<br />

patient.<br />

Physician did not ad<strong>dr</strong>ess side effects <strong>of</strong> treatments/ did not<br />

collaborate with patients.<br />

Patients who met with doctors to receive their diagnosis<br />

reported the experience was negative when doctors simply<br />

lectured and gave the medical aspects <strong>of</strong> the cancer. The<br />

patients explained that when doctors focused on the<br />

medical aspect <strong>of</strong> the cancer, they overlooked the women’s<br />

opinions on how they should be treated. The patients felt<br />

they did not matter when doctors did not answer questions<br />

and failed to give information on what treatment would<br />

mean for their livelihoods. There are several examples in<br />

the transcripts <strong>of</strong> patients being given medications without<br />

full explanations as to what the side effects could be. When<br />

women researched the medications and came back with<br />

questions, <strong>of</strong>ten times the response from the doctor was<br />

negative. In one instance, a woman was prescribed Taxol,<br />

an anti-cancer chemotherapy <strong>dr</strong>ug. The women researched<br />

the <strong>dr</strong>ug and proceeded to talk to her doctor about her<br />

findings. She said,<br />

“When I talked to the doctor about the Taxol, he was so nonunderstanding,<br />

so uncompassionate about it. He’s like well,<br />

just do it and, you know…I mean, he… I don’t feel that I<br />

was respected for my fear or my decision on what this was<br />

going to be, and, um, I felt that it was a valid fear, or a<br />

valid… you know, um, question. And I just felt really<br />

disconnected by the doctor with… you know, it’s like…<br />

okay, well, um, if you want to live you going to do this, um,<br />

without any understanding that what it was for me to live,<br />

you know, what it… what it took for me as a human, as a<br />

person, as an individual, um, you know… if I couldn’t have<br />

my music, or if I couldn’t have… and for some other people<br />

who are passionate about something if they don’t have that<br />

in their lives anymore, how are they going to adjust and how<br />

are they going to survive. Piano or my music to me is really<br />

my coping mechanism for everything else that I do. And to<br />

be left without it… and I don’t think that he had enough<br />

understanding about that.”<br />

This woman is one <strong>of</strong> the many patients who were not<br />

understood when trying to articulate their fears about<br />

medications.<br />

Lack <strong>of</strong> concern for livelihood<br />

Most women reported telling their doctors they were<br />

musicians and asked how treatments would impact their<br />

ability to play. The results show that when the doctors<br />

focused on the cancer first and everything else second, the<br />

women had a negative experience. These women would also<br />

report that the doctors only cared about them as a cancer<br />

patient and not as a whole person with a life outside <strong>of</strong><br />

cancer. The doctors who treated the women simply like a<br />

cancer patient failed to individualize care that would allow<br />

for the women to be able to play music at their current<br />

level post treatment. One participant who sang for a living<br />

was concerned about her ability to sing post treatment.<br />

This woman, among others, reported some doctors did not<br />

understand their lung capacity had been reduced after<br />

treatment. Doctors who did not realize that certain<br />

musicians, such as singers, had extraordinary lung capacity<br />

when compared to a normal person only focused on healing<br />

the patient as a normal person. When measured for lung<br />

capacity, this woman was told she was at ideal levels for a<br />

female, but not at the extraordinary level she once was.<br />

This patient reported that doctors simply did not know<br />

how musicians functioned. She said, “But [doctors] don’t<br />

know, they don’t know what’s necessary for a singer to sing, they<br />

don’t know how those parts work. Aa, aa, it’s like you know I<br />

remember long ago going to an ear, nose, and throat specialist. He<br />

did not understand musicians and he was one <strong>of</strong> those who was<br />

more interested in getting <strong>of</strong>f to his weekend trip so told me there<br />

was nothing wrong with my voice when I couldn’t sing above an<br />

F. This was my upper range; he said my speaking voice was just<br />

fine so my singing voice should be fine.” Women felt they did<br />

not matter to health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals when their concerns<br />

were met with cynicism and doubt.<br />

Did not assist patient with “survivorship”<br />

Many patients also expressed a dislike <strong>of</strong> the attention<br />

given to them post treatment. These patients explained<br />

5

UST McNair Scholars Program Research Journal<br />

that for doctors, it was truly “Cancer first.” When<br />

treatments were over and patients inquired as to what to<br />

do in order to regain their physical capacity to make music,<br />

they found doctors were nonresponsive. A patient who was<br />

a violinist asked her doctors what she should do in order<br />

to be able to hold her instrument for long periods <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

She was given a sheet containing exercises, which included<br />

crawling ones hand up a wall and moving a broomstick up<br />

higher each day. The woman said “I wish they had said a<br />

little bit more about what to do instead <strong>of</strong> just giving me this paper,<br />

here do these exercises.” Several other patients experienced this<br />

same situation, and remarked they would have liked more<br />

attention paid to how they were going to regain their<br />

physical capacity to make music.<br />

MATTERING BEHAVIORS<br />

Physician stayed away from medical jargon / medical team<br />

was encouraging.<br />

When doctors had patience and explained all possible<br />

options to the patient, allowing the patient to make an<br />

informed choice, the patient seemed satisfied. Doctors who<br />

stayed away from medical jargon and strove to not<br />

overwhelm the patient were seen as understanding. An<br />

example <strong>of</strong> this comes from a woman who recalled what it<br />

was like when she was diagnosed. She said, “They gave me a<br />

book at the library, the book had information about what doctors<br />

do when someone is diagnosed. It said they give you a bag with a<br />

bunch <strong>of</strong> stuff in it like a satin pillow case, when your hair falls<br />

out, and about, you know, the people that replaced your eyelashes<br />

and stuff like that. This book actually scared the (*****) out <strong>of</strong><br />

me.” When the woman told her doctor her concerns, he<br />

explained to her what she was reading in the book in nonmedical,<br />

plain terms. She said she was assured by the doctor<br />

that he would explain each treatment procedure to her and<br />

be there during the procedures in case she needed comfort.<br />

Analysis showed this type <strong>of</strong> personal relationship between<br />

both doctor and patient facilitated the thought the patient<br />

mattered. The most desirable doctors were those who in<br />

some cases would encourage the women to continue<br />

playing their music. A woman recalled the help she<br />

received from her health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals by saying “I got<br />

a lot <strong>of</strong> psychological help from my doctor and my nurses, they were<br />

cheering me on saying I was doing great and it was better for me<br />

to keep making music than sit home and worry, which I really<br />

6<br />

agree, I’m glad that I kept playing and teaching.” This type <strong>of</strong><br />

encouragement made women feel as if the cancer was not<br />

going to define who they were. Patients reported these<br />

doctors were truly “human” and made them feel like they<br />

were not just an accumulation <strong>of</strong> cancer cells but a whole<br />

person with feelings. Doctors made patients feel like they<br />

mattered when they treated the women respectfully and<br />

looked at them as a person. A patient stated her doctor was<br />

very nice to her and it “kind <strong>of</strong> makes you feel like I’m not like<br />

old and ugly and cancerous because, you know, he was being so<br />

nice to me.”The women explained the term “human” by<br />

saying that these doctors understood how they were feeling<br />

and were responsive to their needs. These doctors wanted<br />

to heal the patient as a whole person and not just as<br />

cancerous host.<br />

Physical contact (if welcomed by patient).<br />

Some patients found it helpful when the doctor would<br />

make physical contact (e.g. hand on the shoulder) in order<br />

to help them understand that they were not alone in the<br />

ordeal. A patient explained, “He[ the doctor] never seemed alo<strong>of</strong><br />

or cold, or never even on the operating table, you know, when they’re<br />

getting ready to give you all <strong>of</strong> those <strong>dr</strong>ugs, and you know, it’s the<br />

hand on the shoulder and just those little things that they do that<br />

just make you feel so human and not just another patient.” Some<br />

patients, however, did not feel comfortable engaging in this<br />

type <strong>of</strong> physical contact from doctors when they did not<br />

know them well or were just meeting for the first time. A<br />

patient remarked that she disliked contact with her doctor<br />

by saying, “When I got into the <strong>of</strong>fice she was very patronizing.<br />

She put her arm around me. I don’t know this lady. She puts her<br />

arm around me and tells me I have cancer. It was hard to take it<br />

all in with this woman <strong>dr</strong>aped over me.”<br />

Interested in patients’ wellbeing<br />

When doctors asked how treatments were affecting the<br />

patient’s wellbeing, the patient felt they mattered. The<br />

patients reported that it is absolutely essential a person find<br />

a doctor who they not only trust because they are a good<br />

doctor, but somebody they really wants to go and talk to.<br />

It is also important they feel good just being in the doctor’s<br />

presence. A patient stated she loved being in her doctor’s<br />

presence. She went on to say “He was so kind and like he<br />

would put his hand on my shoulder. You know, just he would touch<br />

and um, like ask me questions that didn’t necessarily relate to the

Oluwademilade Adediran<br />

Psychology Mattering<br />

diagnosis, but I just really felt like he cared about how this was<br />

all affecting me as a person.” When doctors made the patient<br />

comfortable, the patient seemed to trust and want to be in<br />

the presence <strong>of</strong> the doctor.<br />

Going above and beyond the call <strong>of</strong> duty<br />

The ultimate behavior that made patients feel they<br />

mattered to their healthcare pr<strong>of</strong>essionals was when doctors<br />

went above and beyond the call <strong>of</strong> duty. Patients reported<br />

extreme approval <strong>of</strong> their doctors when they received a call<br />

from them to see how they were coping with treatments.<br />

The doctors who contacted patients made the participants<br />

feel they mattered because those doctors put the patient<br />

first. Among many examples, there are a few that stand<br />

out. A woman stated that “my doctor would call me, like, um,<br />

during the week after, you know, the surgery or something and just<br />

say yeah, I’m just calling to see if you have any questions, how<br />

are things going and I’m like oh my gosh my doctor is calling me<br />

at 5:30 in the evening just to see how I am!” This patient<br />

experienced satisfaction because this doctor did not have<br />

to call her, but nevertheless, this doctor took time from his<br />

day to make sure his patient was alright. Another example<br />

<strong>of</strong> a doctor going beyond the call <strong>of</strong> duty occurred when a<br />

patient told her doctor that she was a musician. The doctor<br />

asked her if she would be willing to come and play her<br />

music in the hospital. This gesture meant a great deal to<br />

this woman because she was dealing with depression due<br />

to the effects the breast cancer and the treatments were<br />

having on her life and livelihood. She was happy because<br />

she felt she mattered to the doctor and was able to give<br />

back to others in her position by playing her music for<br />

them. In summation, I believe women who experienced<br />

these types <strong>of</strong> interactions felt as if their doctors were<br />

saying “I know that being able to play your music matters<br />

to you. You are my patient and you matter to me, therefore<br />

your ability to play also matters to me.”<br />

THE IMPACT OF DOCTOR-PATIENT INTERACTIONS ON<br />

MATTERING<br />

From the analysis, it appears mattering occurs within a<br />

tw<strong>of</strong>old interaction. Those patients who came in with<br />

questions and had researched what cancer medications can<br />

do to the body felt prepared to interact with the doctor.<br />

Women who either brought a friend to ask questions, or<br />

researched and asked the doctor as many questions they<br />

could felt they mattered when the doctor answered their<br />

questions. A patient recalled her experience with her doctor<br />

by saying “I brought a friend with me because in the midst <strong>of</strong><br />

this you need someone who will be a real advocate. This friend<br />

who went with me, boy, she interrogated the doctor up one side and<br />

down the other. She asked him questions like, how <strong>of</strong>ten have you<br />

done a mastectomy. The doctor was patient and answered<br />

everything.” Patients who came in with questions for the<br />

doctor felt the doctor was competent and caring when he<br />

or she answered the questions. The second portion <strong>of</strong> this<br />

interaction process is that the doctor should respond to the<br />

patient. The doctors who answered all the patient’s<br />

questions were seen as caring and compassionate as well as<br />

competent. A patient called her doctor as “caring” when<br />

the doctor took the time to answer all <strong>of</strong> her queries. The<br />

patient identified above went on to say “I could email her<br />

and she would email me back within hours, ah, and she might<br />

answer and say I am at a conference in China, you know, what<br />

do you want to know? But she was just always there to answer<br />

any questions that I had, no matter where she was. “When<br />

patients and doctors achieved this ideal interaction, the<br />

patient felt they mattered to the doctors as a person and<br />

not just as a cancer patient.<br />

Participant perception <strong>of</strong> “types <strong>of</strong> doctors”<br />

Results from analysis show that patients perceive two<br />

types <strong>of</strong> doctors and two types <strong>of</strong> patients. A patient put it<br />

best by saying, “the first types <strong>of</strong> doctors are those who do not<br />

seem like interaction with patients and simply want to prescribe<br />

medication in order to treat whatever is afflicting the person.” The<br />

second types <strong>of</strong> doctors, just like the first, prescribe<br />

medication to the patient in attempt to heal and give the<br />

individual their life back. The difference between these<br />

doctors lies in the interaction component <strong>of</strong> the second<br />

doctor. The second doctor is also concerned with the<br />

patients’ livelihood during and after treatments and<br />

therefore seeks to interact and understand how treatments<br />

are affecting the individual.<br />

Types <strong>of</strong> patients<br />

Analysis showed there are also two types <strong>of</strong> patients. A<br />

participant articulated what the two types <strong>of</strong> patients were<br />

by saying “there are people who go to the doctor and they don’t<br />

want to know anything and they just want to put their trust in<br />

the doctor and be led and do what the doctor said and that’s maybe<br />

7

UST McNair Scholars Program Research Journal<br />

half. And then there are the patients who want to be participants<br />

by talking one on one with the doctor and want all the information<br />

that is possible and they want to be involved in the decision<br />

making.” Analysis <strong>of</strong> the transcripts shows many women<br />

saying what one patient said best, “there needs to be a match<br />

on the doctors who are comfortable with each kind <strong>of</strong> patients.”<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the participants fit the criteria for the second<br />

patient who wants to be involved in the care they receive<br />

because they wanted to be able to perform their music after<br />

treatments. Many <strong>of</strong> the women gave advice to future<br />

patients by saying “If there is a mismatching <strong>of</strong> the right doctor<br />

to the right patient, there will be conflict and the patient might<br />

not feel cared for.” There are several examples <strong>of</strong> this<br />

mismatching <strong>of</strong> patients to doctors, or instances where<br />

patients did not feel comfortable with the doctors they had.<br />

One particular example occurred with a woman who had<br />

difficulty with her health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. She recalled<br />

and said “I had to deal with so many nonmedical people when<br />

you went for radiation, there were like six people standing around,<br />

you know. And here I’m lying down with my breast hanging down<br />

being ready to get shot up and they were like wearing uniforms.<br />

They looked almost like airline attendants. And I thought why<br />

do they need all <strong>of</strong> these people around here.” This woman felt<br />

uncomfortable with the situation in the operating room.<br />

Though her doctors were in the room, she remarked she<br />

did not feel as if she could talk to them due to the lack <strong>of</strong><br />

intimacy she felt.<br />

Mattering in the long term/Survivorship<br />

Analysis revealed many women looking for support and<br />

a sense they mattered from their doctors after treatments<br />

were over. Most women commented they found they<br />

received the most attention when they were going through<br />

the cancer treatments. When the treatments were over,<br />

they recalled having problems adjusting to their damaged<br />

bodies as relating to performing and making music. A<br />

woman expressed her concern toward this topic by saying<br />

she found doctors focus more on the short term (e.g.<br />

getting rid <strong>of</strong> the cancer) than the long term (e.g. good<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> life). She went on to say, “I don’t think medical<br />

doctors understand holding an instrument for a solid hour, it’s not<br />

easy. I suppose a way to make them understand is to relate it to<br />

some sport. They might have a better understanding that it is very<br />

difficult to hold an instrument after having lymph nodes taken<br />

out.” Almost all <strong>of</strong> the women in this study remarked that<br />

8<br />

there needs to be more attention given to living with the<br />

long term effects <strong>of</strong> cancer treatments. The women<br />

remarked <strong>of</strong>ten they do not want to bother their medical<br />

team when they come in for routine checkups because they<br />

feel the doctors are <strong>of</strong>ten busy with other patients. The<br />

doctors who truly made women feel like they mattered<br />

were the ones who ad<strong>dr</strong>essed these issues. A patient put<br />

best what others were trying to articulate by saying,<br />

“I felt like my all the medical care that I had was excellent.<br />

I don’t find a lot <strong>of</strong> attention to long term care and how are<br />

you are in the long run. I think doctors have a lot <strong>of</strong> time to<br />

surround, mainly when I go to my oncologist appointment,<br />

which I will in April, a few key questions will be asked<br />

and they will get my ****bones and see**** and they will<br />

check on the critical things and do I have cancer. There are<br />

no signs that I have cancer. And sometimes my oncologist does<br />

ask about my comfort level and I guess, I always kind <strong>of</strong> get<br />

the idea, you know, they are busy dealing with people who<br />

are dying from cancer, they are not all that concerned with<br />

how am I doing in the long term. And I have never said<br />

that I’m doing poorly. I have continued to pursue this soreness<br />

and each time I go in I say well, you know, can you, to begin<br />

with I wanted physical therapy and he was willing to, you<br />

know, write a prescription for that and the massage is<br />

helping so he took my massage person’s card, um, but I guess<br />

I would hope for a little bit more attention to the long term<br />

effects.”<br />

CONSEQUENCES OF MATTERING<br />

It is important to note that many women in this study<br />

wanted to matter to their doctors. A patient recalled her<br />

experience with her doctors by saying “I had to switch doctors<br />

because they just didn’t seem to understand, you know. I wanted<br />

someone who would understand and be able to tell me how these<br />

treatments would affect my voice as a musician.” Many patients<br />

echoed what this woman said by saying they preferred the<br />

second type <strong>of</strong> doctor because it seemed this ideal doctor<br />

cared about them as a patient as well as a person.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> this research was to see if patients perceive<br />

they matter to their health care providers. Patients stated<br />

mattering to doctors was very important in receiving quality<br />

care. Patients <strong>of</strong>ten switched doctors when they felt they<br />

didn’t matter to their health care providers. The main

Oluwademilade Adediran<br />

Psychology Mattering<br />

finding from this study was doctors made patients feel like<br />

they mattered when they took the time to talk, answered<br />

questions, and view the patient as a person who wanted to<br />

be able to have good quality <strong>of</strong> life after treatments. The<br />

results also indicated women felt they were merely cancer<br />

patients when they were given their diagnosis over the<br />

phone and by nurses who did not have sufficient<br />

information. Results from the current study coincide with<br />

findings from previous research from Janssen & MacLeod,<br />

(2010) which also found that patients dislike being treated<br />

as only as their cancer and not as people.<br />

This research also investigated whether or not patients<br />

perceived whether doctors took their life and livelihood<br />

into account when prescribing treatments. It seems some<br />

doctors are still focused on the elimination <strong>of</strong> the cancer<br />

and fail to look at long term effects <strong>of</strong> cancer treatments.<br />

Some doctors failed to ad<strong>dr</strong>ess the side effects <strong>of</strong> treatments,<br />

which led to patient difficulty in regaining their livelihood<br />

(Schmalenberger, S., Giebenhain, Gessert, & <strong>St</strong>arr, 2011;<br />

Schmalenberger, Giebenhain, <strong>St</strong>arr, & Gessert, 2011). The<br />

patients from this study remarked if the doctor could give<br />

them back their lives but take away their means <strong>of</strong><br />

providing for themselves, their quality <strong>of</strong> life had been<br />

greatly diminished. Being musicians is their passion,<br />

identity, and way <strong>of</strong> life. These women have trained for a<br />

lifetime to make music, and therefore cannot merely switch<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essions.<br />

Medical treatments are essentially universal and not<br />

individualized. Doctors usually follow the same protocols.<br />

In the present study, largely ignored? Or downplayed the<br />

fact these women were musicians whose careers depend on<br />

their finely tuned physical abilities. Results from this study<br />

indicate when dealing with patients, they perceived the<br />

doctor was concerned with the cancer to the exclusion <strong>of</strong><br />

anything else. Some doctors asked the patient how<br />

treatments were affecting them, but the major focus was<br />

on getting rid <strong>of</strong> the cancer, everything else came second.<br />

Research indicates more women than ever are found to<br />

survive breast cancer. This rise in survival rates can be<br />

attributed to better methods <strong>of</strong> detection and intervention.<br />

Because we are more likely to survive cancer today, it makes<br />

sense that health care providers need to broaden their focus<br />

to include individualized treatments to successfully<br />

eliminate the cancer as well as minimize threats to patients’<br />

careers. This will help maintain the patients’ quality <strong>of</strong> life<br />

after treatments are over.<br />

Taking into consideration the concerns <strong>of</strong> the present<br />

sample, recommendations for improved holistic health care<br />

might include the following: in order for doctors to better<br />

suit their patients and do no harm as the Hippocratic Oath<br />

states, doctors could facilitate better communication with<br />

patients. This could help patients perceive they matter as<br />

people and are not just a name on a chart. Patients ought<br />

to be able to tell their doctors they are a mechanic, surgeon,<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional athlete, or ballet dancer, and therefore must (if<br />

at all possible) be able to do specific activities after<br />

treatments have ended. Doctors ought to share with the<br />

patient all possible treatment options, probabilities <strong>of</strong><br />

success, as well as the pros and cons <strong>of</strong> each treatment<br />

option. This will ensure the patient has input about how<br />

they would like to be treated. Furthermore, health care<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals might consider creating a relationship that<br />

conveys they care for the patient. The relationship need<br />

only include specific characteristics which include: 1) the<br />

doctor could listen to the patient and direct them to<br />

resources which could give the woman further information<br />

about treatment options; 2) the doctor could keep the lines<br />

<strong>of</strong> communication open by making sure that meetings with<br />

the patient last as long as they need to; 3) doctors ought to<br />

take their time when meeting with each patient and not<br />

try to hurry through the process. This patience exhibited<br />

by the doctor could imply to the patient they can share<br />

their thoughts.<br />

The recommendations stated above were found to be<br />

what the ideal doctor should engage in according to study<br />

conducted by Theisel (2010). This “ideal” interaction does<br />

not facilitate more work for the doctor who has many<br />

patients to help, but helps him or her understand where<br />

the patient is coming from. The complaints from the<br />

women were not just that the doctor did not take his or<br />

her time. It was that the doctor was not purposeful in the<br />

use <strong>of</strong> his or her time. A patient explained “I see my surgeon,<br />

oncologist, and radiation oncologist every couple <strong>of</strong> months. And I<br />

have to tell you, when I go in for my treatment there, the visits get<br />

quicker and quicker.” Practical constraints in the age <strong>of</strong><br />

managed care imply it is hard for a doctor to be able to give<br />

each patient the attention they might deserve. Though this<br />

is the case, doctors ought to make their patients feel they<br />

matter by purposefully using the time they are allotted per<br />

9

UST McNair Scholars Program Research Journal<br />

patient. To ad<strong>dr</strong>ess time constraints, the doctor could enlist<br />

the help <strong>of</strong> other health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals such as nurses<br />

and patient navigation advocates in order to make the<br />

patient feel they matter. Research from Kaiser et al. (2009)<br />

indicated the patient is more likely to trust the doctor if<br />

they feel they matter. Much more than this, if the patient<br />

feels they matter to the doctor, they are more likely to trust<br />

other specialists the doctor recommends to them.<br />

Health care providers, such as nurses or patient<br />

navigation advocates, could perhaps also play a bigger role<br />

in making the patient feel like they matter from the very<br />

first phone call to the patient. If the woman must receive<br />

the diagnosis over the phone, the nurse or doctor giving<br />

the news ought to have information for the woman about<br />

the illness, and possible treatment plans. The pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

could take into account the woman’s feelings on the subject<br />

and not be cold in the delivery <strong>of</strong> the news. The health care<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional could attempt to schedule an informational<br />

meeting with the woman as soon as possible, even if an<br />

appointment with the physician is not possible within a<br />

week. This will ensure women do not sit with news <strong>of</strong> their<br />

cancer for weeks without information and support.<br />

When interviewed, the post-breast cancer participants<br />

in the current study had several suggestions for health care<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. A woman remarked she wants doctors to be<br />

concerned with the quality <strong>of</strong> her life after treatments by<br />

saying,<br />

10<br />

“I just feel like, um, the medical community needs to have a<br />

little more understanding <strong>of</strong> what quality <strong>of</strong> life is for an<br />

individual person, not just the treatment but the fact that,<br />

You’re going to live, but are you going to live with good<br />

quality or with just what you need to survive. Living and<br />

surviving and, being successful are really different things to<br />

everybody. You know what I mean. There are different<br />

qualities and different aspects that have to go into all those<br />

things. You know. You can live but if you’re not living the<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> life or the success that you need for your life, then<br />

it seems a lot pointless.”<br />

Results from this study imply there needs to be more<br />

attention to long term side effects from treatments, and<br />

strategies to cope with and heal from those side effects. A<br />

woman in this study remarked there have been<br />

improvements, but there is still work to do. The woman<br />

went on to say, [the medical center I go to] “has a newsletter<br />

that goes out to patients that have had breast cancer and I have<br />

seen more awareness developing in that <strong>of</strong> sort <strong>of</strong> like long term<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> thing, you know, exercise classes or what are the effects<br />

after you have had cancer 10, 5-10 years later. I have seen a little<br />

bit more attention given to the issue rather than just talking about<br />

it.” This study shows what many breast cancer patients are<br />

sure to agree with: having breast cancer is not just<br />

something someone has at some point in their life, it is<br />

something the person has to deal with her entire life. Due<br />

to this factor, doctors should give more attention to post<br />

treatment or survivorship issues.<br />

In order to ad<strong>dr</strong>ess long-term survivorship issues, there<br />

could be a specialist who provides occupational assessments<br />

for patients. These exist in some breast centers today. The<br />

specialist assesses the patient’s physical abilities prior to<br />

any form <strong>of</strong> treatment in order to see what it is the patient<br />

does for a living. For example, a patient might receive an<br />

assessment that discovers he or she is a pianist. This would<br />

be particularly helpful because the occupational assessment<br />

specialist can pinpoint the muscles and ligaments in the<br />

arms involved in playing piano. Doctors would receive this<br />

information and would therefore be careful <strong>of</strong> these<br />

locations, or perhaps pick other lymph nodes in the arms<br />

to remove if possible. Better quality <strong>of</strong> life would be<br />

reached if doctors are aware this patient needs to be able<br />

to play the piano after treatment. They would be more<br />

careful to place ports or <strong>dr</strong>ains in locations that would<br />

facilitate less harm to the patient.<br />

Another way to learn about survivorship issues would<br />

be to create more survivor support groups. When women<br />

were diagnosed in this study, they recalled being given<br />

information about several focus groups that could help<br />

them deal with the issues they were having adjusting to<br />

life with cancer. There could be more groups focused on<br />

the issues women have post-cancer treatments. These<br />

groups ought not to be focused on simply stating<br />

grievances women have, because many patients stated they<br />

did not want to feel sorry for themselves, but they should<br />

focus on support from other patients who have been<br />

through what they were now undergoing (Johnson, 2010).<br />

Doctors and other health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals should interact<br />

with the patients in order to ascertain what women need<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> support. It could be the case that some women<br />

want hard facts about survival rates and statistics while<br />

some patients want to be in a group setting where they can<br />

talk about the issues they are having. Interaction with

Oluwademilade Adediran<br />

Psychology Mattering<br />

patients will help doctors understand the patient and their<br />

needs, so they can direct patients to appropriate resources.<br />

This research was conducted with only interviews from<br />

patients and not health care providers. It would be<br />

interesting for future research to acquire interviews from<br />

doctors as well. This would provide an understanding<br />

about how health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals view their interactions<br />

with patients. In summation, the health care field, though<br />

has made many advances, still needs to focus on individual<br />

patients. Doctors could perhaps see patients as someone’s<br />

father, mother, sister, or brother, and therefore understand<br />

the patient as a whole matters. If the focus <strong>of</strong> health care<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals shifts from not just curing a disease but to<br />

also ensure the livelihoods <strong>of</strong> patients are protected,<br />

patients might experience higher qualities <strong>of</strong> life. In<br />

addition, if the patient matters to the doctor, it might be<br />

easier for doctors to see the patient as a person, and<br />

therefore the doctor will involve patients in making<br />

decisions. If the patient matters to the doctor, then this<br />

could imply the doctor will keep the patients’ interests in<br />

mind. When the doctor says the diagnosis is cancer, it is a<br />

challenge to not only to defeat the cancer but to return to<br />

life after the treatments are over. Doctors ought to feel an<br />

obligation, as stated by the Hippocratic Oath, to work to<br />

integrate quality treatments into good quality <strong>of</strong> life for<br />

patients.<br />

In summation, this research identified two primary areas<br />

that require attention from health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. First,<br />

there needs to be better interactions with the patient as was<br />

also found in the study conducted by Kaiser (Kaiser et al.,<br />

2009). Second, there ought to be more thought given to<br />

long term effects <strong>of</strong> cancer treatments and the woman<br />

should continue to matter over time. Though the next<br />

steps <strong>of</strong> this research points to viewing health care<br />

provider’s views on mattering, the more immediate step is<br />

to focus on occupational assessments. As this study has<br />

demonstrated, <strong>of</strong>ten times doctors do not take into account<br />

the patients livelihood when prescribing treatments. Next<br />

steps in research will not only look at health care providers<br />

views on mattering, but also look at ways to implement<br />

occupational assessments in more treatment centers.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

American Cancer Society. (2010). Survival rates for breast cancer<br />

by stage. Retrieved from www.cancer.org/Cancer/<br />

ProstateCancer/DetailedGuide/prostate-cancer-survival-rates<br />

Connolly, K. M. (2002). Work: Meaning, mattering, and job<br />

satisfaction. In D. S. Sandhu (Ed.), Counseling employees: A<br />

multifaceted approach. (pp. 3-15) Alexan<strong>dr</strong>ia, VA, US:<br />

American Counseling Association.<br />

Dibbelt, S., Schaidhammer, M., Fleischer, C., & Greitemann, B.<br />

(2009). Patient–doctor interaction in rehabilitation: The<br />

relationship between perceived interaction quality and longterm<br />

treatment results. Patient Education and Counseling,<br />

76(3), 328-335. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.031<br />

France, M. K., & Finney, S. J. (2009). What matters in the<br />

measurement <strong>of</strong> mattering?: A construct validity study.<br />

Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development,<br />

42(2), 104-120. doi:10.1177/0748175609336863<br />

Janssen, A. L., & MacLeod, R. D. (2010). What can people<br />

approaching death teach us about how to care? Patient<br />

Education and Counseling, 81(2), 251-256. doi:10.1016/<br />

j.pec.2010.02.009<br />

Johnson, A. (2010) Informational Social Support: Female<br />

Musicians Cope with Breast Cancer<br />

Kaiser, K., Rauscher, G. H., Jacobs, E. A., <strong>St</strong>renski, T. A.,<br />

Ferrans, C. E., & Warnecke, R. B. (2011). The import <strong>of</strong> trust<br />

in regular providers to trust in cancer physicians among<br />

white, african american, and hispanic breast cancer patients.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> General Internal Medicine, 26(1), 51-57.<br />

doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1489-4<br />

Kawamura, S., & Brown, S. L. (2010). Mattering and wives’<br />

perceived fairness <strong>of</strong> the division <strong>of</strong> household labor. Social<br />

Science Research, 39(6), 976-986. doi:10.1016/<br />

j.ssresearch.2010.04.004<br />

Landmark, B. T., bøhler, A., Loberg, K., & Wahl, A. K. (2008).<br />

Women with newly diagnosed breast cancer and their<br />

perceptions <strong>of</strong> needs in a health-care context: A focus group<br />

study <strong>of</strong> women attending a breast diagnostic center in<br />

norway. Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Nursing, 17(7), 192-200.<br />

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02340.x<br />

National Cancer Institute. (2010). Survival statistics. Retrieved<br />

from http://www.cancer.gov/statistics/glossary/survival<br />

O’Connor, S. J. (2011). Listening to patients: The best way to<br />

improve the quality <strong>of</strong> cancer care and survivorship. European<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Cancer Care, 20(2), 141-143. doi:10.1111/j.1365-<br />

2354.2011.01242.x<br />

Rayle, A. D. (2005). Adolescent gender differences in mattering<br />

and wellness. Journal <strong>of</strong> Adolescence, 28(6), 753-763.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.10.009<br />

Salonen, P., Kellokumpu Lehtinen, P., Tarkka, M., Koivisto, A.,<br />

& Kaunonen, M. (2011). Changes in quality <strong>of</strong> life in patients<br />

11

UST McNair Scholars Program Research Journal<br />

with breast cancer. Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Nursing, 20(1-2), 255-<br />

266. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03422.x<br />

Sanson-Fisher, R., Bailey, L. J., Aranda, S., D’Este, C.,<br />

<strong>St</strong>ojanovski, E., Sharkey, K., & Sch<strong>of</strong>ield, P. (2010). Quality<br />

<strong>of</strong> life research: Is there a difference in output between the<br />

major cancer types? European Journal <strong>of</strong> Cancer Care, 19(6),<br />

714-720. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01158.x<br />

Schmalenberger, S., Giebenhain, J.E., Gessert, C.E., & <strong>St</strong>arr, L.<br />

(2011, July). The disabling affects <strong>of</strong> breast cancer treatment<br />

on women musicians. Paper session presented at the<br />

Minnesota Symposium in Disability <strong>St</strong>udies. Mpls, MN.<br />

Schmalenberger S, Giebenhain J, <strong>St</strong>arr L, & Gessert C E. (2008).<br />

The medical and occupational well-being <strong>of</strong> musicians after<br />

breast cancer. American Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Oncology 31(5), 517.<br />

Schmalenberger, S., Giebenhain, J.E., <strong>St</strong>arr, L., & Gessert, C.E.<br />

(2011, July). Musician survivors: Breast cancer’s effect on<br />

their livelihood. Paper session presented at the 29th Annual<br />

Symposium <strong>of</strong> the Performing Arts Medicine Association.<br />

Aspen, CO.<br />

Theisel, S., Schielein, T., & Spleßl, H. (2010). Der „ideale“ arzt<br />

aus sicht psychiatrischer patienten. [the “ideal” doctor from<br />

the view <strong>of</strong> psychiatric patients.]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 37(6),<br />

279-284. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1248403<br />

Tucker, C., Dixon, A., & Griddine, K. (2010). Academically<br />

successful African American male urban high school<br />

students’ experiences <strong>of</strong> mattering to others at school.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essional School Counseling, 14(2), 135-145.<br />

12

Oluwademilade Adediran<br />

Psychology Mattering<br />

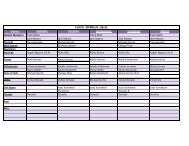

Section one<br />

Themes<br />

Doctor did not consider the patient’s<br />

whole life<br />

Section one<br />

Doctors did not understand music was a<br />

big part <strong>of</strong> the patient’s life:<br />

Doctors did not understand their patients<br />

Section one<br />

Lack <strong>of</strong> intimacy and sensitivity by staff:<br />

IMPORTANT MATTERING QUOTES FROM PARTICIPANTS<br />

The following quotes below are behaviors exhibited by healthcare<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals patients felt were cold or alo<strong>of</strong>. The main finding in this section<br />

was patients felt the doctors could have done more to make them feel more<br />

comfortable and like they cared for their wellbeing outside <strong>of</strong> removing the<br />

cancer. i.e. seeing how cancer treatment would affect their music playing<br />

Quotes from patients<br />

“Well, when we talked about the Taxol the doctor was so non-understanding, so<br />

uncompassionate about it. “The doctor said if you want to live you got to do this,<br />

without any understanding <strong>of</strong> what it was for me to live, you know, what it took for<br />

me as a human, as a person, as an individual. If I couldn’t have my music, or if I<br />

couldn’t have… and for some other people who are passionate about something if<br />

they don’t have that in their lives anymore, how are they going to adjust and how<br />

are they going to survive. Because piano to me, or my music to me is really my<br />

coping mechanism for everything else that I do. And to be left without it I don’t<br />

think that there’s enough understanding about that.”<br />

“They [doctors] don’t know, they don’t know what’s necessary, they don’t know how<br />

those parts work. Aa, aa. I remember long ago going to an ear, nose, and throat<br />

specialist, um, who did not understand musicians and he was one <strong>of</strong> those who was<br />

more interested in getting <strong>of</strong>f to his weekend trip so told me there was nothing<br />

wrong with my voice when I couldn’t sing above an F, you know, in my upper range.<br />

He said my speaking voice was just fine so he thought.”<br />

“The first thing that happened? They gave me a book at the library. What they do<br />

when someone is newly diagnosed is they give you a bag with a bunch <strong>of</strong> stuff in it<br />

like a satin pillow case, when your hair falls out, and you know, the people that<br />

replaced your eyelashes and stuff like that. They give you a book which actually<br />

scared the (*****) out <strong>of</strong> me.”<br />

“I got to tell you it’s like a parallel universe were I was treated. They kind <strong>of</strong> function<br />

like the New York City Board <strong>of</strong> Ed in that they have so many nonmedical personnel<br />

around there, the way the Board <strong>of</strong> Ed. It continues to astound me how many noneducation<br />

people they have there. Taking up space, taking up payroll, taking up<br />

money. The hospital I went to was that way also. You know, you’d go outside and<br />

you’d see all the uniforms out there standing around on a cigarette break and I’m<br />

thinking this is a (*****) cancer hospital. I bet I mean I had to deal with so many<br />

nonmedical people when you went for radiation, there were like six people standing<br />

around, you know. And here I’m lying down with my breast hanging down being<br />

ready to get shot up and they were like wearing uniforms. They looked almost like<br />

airline attendants. And I thought why do they need all <strong>of</strong> these people around here.<br />

You know, I mean maybe I should be grateful that these surroundings were pretty,<br />

you know, like with flowers and nice painting and nice carpeting, but all I could<br />