Klosterführung_internet

Erfolgreiche ePaper selbst erstellen

Machen Sie aus Ihren PDF Publikationen ein blätterbares Flipbook mit unserer einzigartigen Google optimierten e-Paper Software.

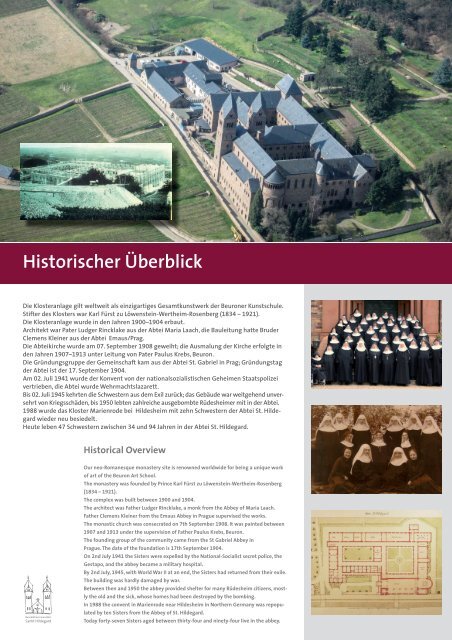

Historischer Überblick<br />

Die Klosteranlage gilt weltweit als einzigartiges Gesamtkunstwerk der Beuroner Kunstschule.<br />

Stifter des Klosters war Karl Fürst zu Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg (1834 – 1921).<br />

Die Klosteranlage wurde in den Jahren 1900–1904 erbaut.<br />

Architekt war Pater Ludger Rincklake aus der Abtei Maria Laach, die Bauleitung hatte Bruder<br />

Clemens Kleiner aus der Abtei Emaus/Prag.<br />

Die Abteikirche wurde am 07. September 1908 geweiht; die Ausmalung der Kirche erfolgte in<br />

den Jahren 1907–1913 unter Leitung von Pater Paulus Krebs, Beuron.<br />

Die Gründungsgruppe der Gemeinschaft kam aus der Abtei St. Gabriel in Prag; Gründungstag<br />

der Abtei ist der 17. September 1904.<br />

Am 02. Juli 1941 wurde der Konvent von der nationalsozialistischen Geheimen Staatspolizei<br />

vertrieben, die Abtei wurde Wehrmachtslazarett.<br />

Bis 02. Juli 1945 kehrten die Schwestern aus dem Exil zurück; das Gebäude war weitgehend unversehrt<br />

von Kriegsschäden, bis 1950 lebten zahlreiche ausgebombte Rüdesheimer mit in der Abtei.<br />

1988 wurde das Kloster Marienrode bei Hildesheim mit zehn Schwestern der Abtei St. Hildegard<br />

wieder neu besiedelt.<br />

Heute leben 47 Schwestern zwischen 34 und 94 Jahren in der Abtei St. Hildegard.<br />

Historical Overview<br />

Our neo-Romanesque monastery site is renowned worldwide for being a unique work<br />

of art of the Beuron Art School.<br />

The monastery was founded by Prince Karl Fürst zu Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg<br />

(1834 – 1921).<br />

The complex was built between 1900 and 1904.<br />

The architect was Father Ludger Rincklake, a monk from the Abbey of Maria Laach.<br />

Father Clemens Kleiner from the Emaus Abbey in Prague supervised the works.<br />

The monastic church was consecrated on 7th September 1908. It was painted between<br />

1907 and 1913 under the supervision of Father Paulus Krebs, Beuron.<br />

The founding group of the community came from the St Gabriel Abbey in<br />

Prague. The date of the foundation is 17th September 1904.<br />

On 2nd July 1941 the Sisters were expelled by the National-Socialist secret police, the<br />

Gestapo, and the abbey became a military hospital.<br />

By 2nd July, 1945, with World War II at an end, the Sisters had returned from their exile.<br />

The building was hardly damaged by war.<br />

Between then and 1950 the abbey provided shelter for many Rüdesheim citizens, mostly<br />

the old and the sick, whose homes had been destroyed by the bombing.<br />

In 1988 the convent in Marienrode near Hildesheim in Northern Germany was repopulated<br />

by ten Sisters from the Abbey of St. Hildegard.<br />

Today forty-seven Sisters aged between thirty-four and ninety-four live in the abbey.

Konventzimmer<br />

„Sie sollen einander in gegenseitiger Achtung zuvorkommen; ihre körperlichen und charakterlichen<br />

Schwächen sollen sie mit unerschöpflicher Geduld ertragen; im gegenseitigen Gehorsam<br />

sollen sie miteinander wetteifern; keiner achte auf das eigene Wohl, sondern mehr auf das des<br />

anderen.“<br />

„Die Bruderliebe sollen sie einander selbstlos erweisen; in Liebe sollen sie Gott fürchten; ihrem<br />

Abt seien sie in aufrichtiger und demütiger Liebe zugetan. Christus sollen sie überhaupt nichts<br />

vorziehen. Er führe uns gemeinsam zum ewigen Leben.“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Kap. 72, 4 - 12)<br />

Im Konventzimmer trifft sich die Gemeinschaft drei bis vier Mal wöchentlich am Abend vor der<br />

Komplet zur Rekreation (von lat. recreatio = Erholung). Hier kommen die Schwestern zusammen,<br />

um sich über Gott und die Welt und über die kleinen und großen Dinge des persönlichen<br />

Lebens der einzelnen und der Gemeinschaft auszutauschen.<br />

Das Konventzimmer ist auch der Raum für Vorträge, Gesprächsrunden, Konferenzen, Gesangsstunden<br />

und fürs gemeinsame Musizieren. Hier finden auch die Klosterfeste zu besonderen Anlässen<br />

und Festtagen statt. Die Hochbänke dienen dabei in einer großen Gemeinschaft wie der<br />

unsrigen der besseren Kommunikation.<br />

The Community’s Common Room<br />

“Thus they should anticipate one another in honor (Rom. 12:10); most patiently endure<br />

one another‘s infirmities, whether of body or of character; vie in paying obedience one<br />

to another … no one following what she considers useful for herself, but rather what benefits<br />

another …“<br />

“Tender the charity of sisterhood chastely; fear God in love; love their Abbess with a sincere<br />

and humble charity; prefer nothing whatever to Christ. And may He bring us all together<br />

to life everlasting! “<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 72, 4 - 12)<br />

It is in the convent’s common room that the community assembles three or four evenings<br />

a week for recreation (from the Latin “recreatio“) before the evening prayer. Here<br />

the Sisters come together to talk about God, the world, the important and the unimportant,<br />

and apects both of their personal life and that of the community.<br />

This room is also used for lectures, conversations, discussion groups, conferences, choir<br />

practices and joint musical performances. This is also where the community holds festivities<br />

on High days and holidays. For a big community such as ours the elevated benches<br />

also help to improve communication.

Kapitelsaal<br />

„Sooft es sich im Kloster um eine wichtige Angelegenheit handelt, soll der Abt die ganze Klostergemeinde<br />

zusammenrufen und selbst die Angelegenheit vortragen ... Dass zur Beratung alle<br />

gerufen werden, bestimmen wir deshalb, weil der Herr oft einem Jüngeren offenbart, was das<br />

Bessere ist.“ (Benediktsregel, Kap. 3, 1.3)<br />

Der Kapitelsaal ist der Ort, an dem alle Entscheidungen getroffen werden und alle Riten stattfinden,<br />

die für die Gemeinschaft von grundlegender Bedeutung sind. Der Name Kapitelsaal<br />

geht auf die alte Tradition zurück, dass in diesem Raum früher täglich ein Kapitel aus der Benediktsregel<br />

vorgelesen wurde. Heute geschieht dies vor dem Abendessen im Refektorium<br />

(Speisesaal).<br />

Wenn jemand neu ins Kloster eintritt, findet hier im Kapitelsaal nach Ablauf einer ersten Probezeit<br />

die Aufnahme in das Noviziat statt. Die neue Mitschwester erhält das Ordensgewand und<br />

in der Regel auch einen neuen Namen.<br />

Im Kapitelsaal werden auch die ersten, zeitlichen Gelübde abgelegt (die Bindung für drei Jahre).<br />

Und hier findet dann auch der Teil der endgültigen, feierlichen Professfeier statt, in dem<br />

die Neuprofesse von der Gemeinschaft empfangen wird.<br />

Im Kapitelsaal finden auch alle Abstimmungen bei wichtigen Entscheidungen der Gemeinschaft<br />

statt. Hier werden die Äbtissin und das engere Beratungsgremium der Äbtissin gewählt.<br />

Zuletzt schließlich wird jede Mitschwester nach ihrem Tod drei Tage lang im Kapitelsaal aufgebahrt,<br />

so dass alle Schwestern und auch die Verwandten sich von der Verstorbenen würdevoll<br />

verabschieden können.<br />

The Chapter Room<br />

“Whenever any important business has to be done in the monastery, let the Abbot call<br />

together the whole community and state the matter to be acted upon. The reason we<br />

have said that all should be called for counsel is that the Lord often reveals to the<br />

younger what is best.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 3, 1.3)<br />

The chapter room is the place where all decisions are taken and all rites which are fundamental<br />

to the community are observed. The name chapter room dates back to the old<br />

tradition according to which a chapter from the Rule of St. Benedict would be read out<br />

in this room every day. Today this happens in the refectory before the evening meal.<br />

Whenever someone wants to join our community, it is in this chapter chamber that she<br />

is officially welcomed into the novitiate after a trial period. The new Sister receives the<br />

habit of the Benedictine order and normally also a new monastic name.<br />

It is in the chapter chamber, too, that the first temporary vows are taken, which are binding<br />

for three years. When the new member of the community is ceremoniously received<br />

into the Benedictine order, parts of the final solemn profession celebrations are also<br />

held here.<br />

The chapter room is also the place where all elections and important decisions of the<br />

community are taken. Here the abbess and the members of her senior advisory committee<br />

are elected here, too.<br />

Finally, the chapter room is where every convent sister is laid out after her death for<br />

three days so that the whole community and also the relatives can take leave of her in<br />

dignity.

Lectio divina – Geistliche Schriftlesung<br />

„Zu bestimmten Zeiten sollen sie sich mit heiliger Lesung beschäftigen.“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Kap. 48,1)<br />

Die geistliche Schriftlesung (Lectio divina) gehört für Benediktinerinnen und Benediktiner zum täglichen<br />

Brot. Sie wird aber auch von vielen Christen heute wieder als wichtiger Bestandteil ihres Lebens<br />

entdeckt. Sie ist ein probates Mittel, sich dem Kern des Wortes Gottes in vier Schritten zu nähern.<br />

Lectio – Lesung<br />

Im Wort der Heiligen Schrift spricht Gott selbst zu uns, ganz konkret und immer neu und aktuell.<br />

Die Heilige Schrift ist der bevorzugte Ort der Begegnung mit Gott. Deshalb ist das Lesen der Schrifttexte<br />

(leise oder halblaut murmelnd) der erste Schritt.<br />

Meditatio – Betrachtung<br />

Die Meditation vertieft und verarbeitet den Text. „Meditari“ heißt, einen Text lesen, ihn mit Leib<br />

und Seele erfassen, ihn im Gedächtnis behalten und mit ganzem Willen in die Tat umsetzen. Die<br />

Meditation fordert Mühe, Willenskraft und Ausdauer. Erst dieser Prozess weckt in uns die Sehnsucht,<br />

Gott tiefer zu erkennen und zu erfahren.<br />

Oratio – Gebet<br />

Es kommt der Augenblick, wo wir unser Verlangen nach der Begegnung mit Gott ins Wort, d.h. ins<br />

Gebet, bringen möchten. Hier geht es um eine bestimmte Weise des Bittgebetes, das Offenheit und<br />

Bereitschaft voraussetzt, die Gnade Gottes zu empfangen und sie mit unserem eigenen Leben zu<br />

beantworten.<br />

Contemplatio – Anschauung Gottes<br />

In der Kontemplation wissen wir uns urplötzlich von Gottes Gegenwart ergriffen. In uns wird ein<br />

tiefes Verlangen nach der Anschauung Gottes geweckt. All das entzieht sich rationaler Darlegung.<br />

Solche Sternstunden - biblisch gesprochen: Tabor-Erlebnisse – sind ein Vorgeschmack des Himmels,<br />

immer im Wissen darum, dass die letzte Vollendung noch aussteht.<br />

Lectio divina –<br />

The spiritual Reading from the Scriptures.<br />

“At certain times they should be occupied with sacred reading.”<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 48, 1)<br />

The spiritual reading is a daily routine for Benedictine Sisters and Brothers. Now, though,<br />

it has also been rediscovered by many Christians as an important part of their lives. It is<br />

an appropriate way of gaining access to the nucleus of God`s word in four steps:<br />

Lectio - Reading<br />

Through the word of the Holy Gospel God himself speaks to us, very concretely and always<br />

anew and with relevance. The Holy Gospel is the preferred venue for meeting God.<br />

This is why the reading of the texts from the Holy Gospel (in silence or murmured) is the<br />

first step.<br />

Meditatio – Meditation<br />

The text is enhanced and interpreted by meditation. “meditare” means reading a text,<br />

comprehending it with body and soul, keeping it in mind and wanting to do what is says.<br />

Meditation demands work, willpower and endurance. This alone is what inspires our<br />

desire to reach a deeper awareness and understanding of God.<br />

Oratio – Prayer<br />

There comes a moment when we want to express our desire to approach God through<br />

words. This is a special form of invocation which implies our openness and the willingness<br />

to receive the mercy of God and to respond to it in our own lives.<br />

Contemplatio – The adoration of God<br />

In contemplation we feel all of a sudden deeply stirred by God`s presence, and yearn to<br />

adore God. These feelings are beyond rational explanations. Such great moments – in biblical<br />

terms “Tabor experiences” - are a foretaste of heaven. And at the same time we are<br />

always aware that the final fulfilment has yet to come.

Bibliothek<br />

„Nach Tisch sind sie frei für ihre Lesungen … die Älteren sollen nachsehen, ob sich keiner findet,<br />

der an geistiger Trägheit leidet und sich dem Müßiggang oder dem Geschwätz überlässt, statt<br />

aufmerksam zu lesen, und damit nicht nur sich selbst schadet, sondern auch andere ablenkt.“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Kap. 48, 13.17)<br />

Seit dem frühen Mittelalter sind die benediktinischen Klöster „Kulturträger“. Die Pflege und<br />

Weitergabe von Wissenschaft, Kultur und Bildung gehörten immer zu ihren besonderen Aufgaben.<br />

Die Lektüre ist Teil unseres geistlichen Lebens. Dieses schließt geistige Tätigkeit mit ein,<br />

z.B. die Beschäftigung mit der Heiligen Schrift, der Theologie und der Liturgie. Das zeigt sich<br />

besonders in den Klosterbibliotheken und in deren Ausgestaltung. Sinnbild für das Lesen sind<br />

in unserer Bibliothek die Deckenausmalungen: sie zeigen symbolisch die großen Kirchenväter<br />

und - mütter sowie die Mönchs- und Wüstenväter und die großen benediktinischen Schriftsteller<br />

durch die Jahrhunderte.<br />

Unsere Bibliothek umfasst ca. 60.000 Bände und ist auf mehrere Abteilungen (Theologie, Liturgie,<br />

Geschichte, Psychologie, Kunst, Musik, Literatur etc.) und Bibliotheksräume verteilt.<br />

Über alte Bestände aus dem alten Kloster Eibingen verfügen wir nicht. Die Handschriften und<br />

Bücher, die vor der Säkularisation und Aufhebung des Klosters 1802 gerettet werden konnten,<br />

befinden sich heute in der Hessischen Landesbibliothek in Wiesbaden.<br />

Das wertvollste Buch unserer Bibliothek ist die Handkopie auf Pergament des Rupertsberger<br />

SCIVIAS-Kodex der heiligen Hildegard, die in den Jahren 1928-1932 in unserer Abtei angefertigt<br />

wurde. Da das Original der Rupertsberger Handschrift mit den 35 berühmten und wertvollen<br />

Miniaturen seit dem Zweiten Weltkrieg als verschollen gilt, hat „unser“ SCIVIAS-Kodex heute<br />

Originalwert und stellt die einzige Überlieferung des illuminierten Hauptwerkes Hildegards dar.<br />

The Library<br />

“After the meal let them apply themselves to their reading or to the Psalms … But certainly one<br />

or two of the seniors should be deputed to go about the monastery at the hours when the sisters<br />

are occupied in reading and see that there be no lazy sister who spends her time in idleness<br />

or gossip and does not apply herself to the reading, so that she is not only unprofitable to herself<br />

but also distracts others.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 48, 13.17)<br />

Benedictine monasteries have been centres of culture since the early Middle Ages. Their special<br />

duties have always included the preservation and the passing on of science, culture and education.<br />

Reading is part of our spiritual life. This involves spiritual practises such as giving priority to<br />

the Holy Gospel, theology and liturgy. This becomes evident in the design and lay-out of monastic<br />

libraries.<br />

The ceiling frescoes in our library are symbols of reading, depicting the great Mothers and<br />

Fathers of the Church as well as the famous monks and desert fathers and the well-known<br />

Benedictine authors down the centuries.<br />

Our library contains 60,000 volumes which are divided to several sections (theology, liturgy, history,<br />

psychology, art, music, literature etc.) and split up in various rooms.<br />

We do not possess stocks from the old monastery in Eibingen. The manuscripts and books which<br />

could be saved prior to secularization and the dissolution of the monasteries in 1802 are now<br />

kept in the Hessian Landesbibliothek in Wiesbaden.<br />

The most valuable book in our library is the vellum-bound copy of the Rupertsberger SCIVIAS<br />

Codex of St Hildegard, which was produced in our abbey from 1928 to 1932. As the original is<br />

said to be lost “our“ SCIVIAS-Codex is of original value and represents the only written record of<br />

the illuminated main work of St Hildegard.

Kirche / Nonnenchor<br />

„Das Oratorium soll sein, was sein Name besagt – Ort des Gebets – und nichts anderes soll dort<br />

getan … werden.“ (Benediktsregel, Kap. 52,1)<br />

Die Abteikirche St. Hildegard wurde in den Jahren 1900-1904 errichtet. Planung und Durchführung<br />

des Kirchenbaus lagen in der Hand von Pater Ludger Rincklake (1850-1927), Mönch<br />

der Abtei Maria Laach. Die Grundsteinlegung erfolgte am 02. Juli 1900; geweiht wurde die<br />

Kirche am 07. September 1908. Die Innenausmalung erfolgte in den Jahren 1907-1913 unter<br />

Leitung von Pater Paulus Krebs (1849-1935), einem Schüler von Pater Desiderius Lenz (1832-<br />

1928), dem Begründer der Beuroner Kunstschule. Die Abteikirche St. Hildegard gilt weltweit<br />

als einzigartige Gesamtkomposition dieser Kunstrichtung.<br />

An den Altarraum der Kirche schließt sich nach Norden hin der Nonnenchor an, in dem jede<br />

einzelne Schwester ihren festen Platz hat und die Gemeinschaft fünfmal am Tag zum Gebet<br />

zusammenkommt. Über dem Chorgestühl erhebt sich die Orgel, die mit ihren 32 Registern<br />

zum Lob Gottes erklingt und sowohl für die Begleitung der Liturgie und des Stundengebets als<br />

auch für Konzerte geeignet ist.<br />

Das Innere des Kirchenraumes wird von der monumentalen Christusfigur in der Apsis bestimmt.<br />

Christus erscheint als Pantokrator, als König und Herrscher über das All, zugleich aber<br />

als Bruder, der jeden mit offenen Armen empfängt und aufnimmt. Er, Christus, ist nicht nur<br />

der Mittelpunkt der Kirche, sondern auch der Mittelpunkt unseres benediktinischen Lebens.<br />

Seinem Wort und Beispiel nachzufolgen sind wir hier; ihn wollen wir suchen und seine Gegenwart<br />

bezeugen, immer und in allem.<br />

The Abbey Church and the Nuns’ Chancel<br />

Für eine Audiotour durch<br />

die Kirche, scannen Sie<br />

bitte den QR-Code.<br />

Mobile users please scan<br />

the image to access the<br />

recording.<br />

“Let the oratory be what it is called, a place of prayer;<br />

and let nothing else be done there“.<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 52, 1)<br />

The abbey church of St Hildegard was erected between 1900 and 1904. It was planned<br />

and realized by Father Ludger Rincklake (1850-1927), a monk at the Abbey of Maria<br />

Laach. The foundation stone was laid on 2nd July 1900. The interior paintings were executed<br />

between 1907 and 1913 by Father Paulus Krebs (1849-1935), a disciple of Father<br />

Desiderius Lenz (1832 – 1928), the founder of the Beuron School of Art. The abbey<br />

church of St Hildegard is widely regarded as a uniquely comprehensive composition of<br />

this kind of art.<br />

Adjacent to the altar room, facing northwards, is the nuns’ choir, where every Sister has<br />

her allocated choir stall and where the community convenes for prayer five times a day.<br />

The organ rises above the choir stalls. It has thirty-two registers which sound to praise<br />

God. As well as accompanying the liturgy, it is also suited for concerts.<br />

The interior of the church is dominated by the monumental figure of Christ in the apse.<br />

Christ appears as “pantocrator”, as king and sublime ruler of the universe, but at the<br />

same time as man’s brother who welcomes and receives everyone with outstretched<br />

arms. Christ is not only the centre of the abbey church, but also of our Bendictine life.<br />

We are here to follow His word and example. It is He whom we want to seek and He<br />

whose presence we want to find everywhere, in everyone, every day anew.

Gregorianischer Choral<br />

„Cantare amantis est – das Singen ist Sache dessen, der liebt.“ (hl. Augustinus)<br />

Der Gregorianische Choral gehört zur ältesten musikalischen Tradition des Christentums und<br />

reicht bis ins 8. Jahrhundert zurück. In ihm drückt sich die Botschaft des Evangeliums, unser<br />

Glaube, auf einzigartige Weise aus. Das ist der Grund, warum wir von den Anfängen unserer<br />

Klostergeschichte an bis heute den Gregorianischen Choral in lateinischer Sprache besonders<br />

pflegen und unser ganzes Stundengebet und die tägliche Eucharistiefeier im Gregorianischen<br />

Choral singen.<br />

Der Gregorianische Choral ist für unser geistliches Leben unentbehrlich, in ihm wird der Alltag<br />

von der Liturgie durchdrungen und getragen. Er führt uns jeden Tag neu in das Zentrum unseres<br />

Glaubens, die Heilige Schrift. Auf unnachahmliche Weise ist es den Komponisten gelungen,<br />

Schüsselstellen der Heiligen Schrift in Musik umzusetzen und dabei Wort und Melodie miteinander<br />

in Einklang zu bringen. Wenn wir diese Gesänge singen, so lassen wir uns je neu auf<br />

Gott und auf sein Wort ein. Lob und Dank, Bitte und Klage, Freuden, Nöte und Sorgen, alle Facetten<br />

des menschlichen Lebens werden vor Gott getragen und ihm entgegengesungen.<br />

Fast unmerklich erfahren wir, dass das Wort des heiligen Augustinus stimmt: „Cantare amantis<br />

est - Das Singen ist Sache dessen, der liebt“ Es ist Ausdruck dafür, was das Ziel allen Gebetes<br />

und jeder Meditation ist: die Kontemplation, d. h. die reine Hingabe, das liebende Verweilen<br />

bei Gott, die Vereinigung mit Ihm, manchmal auch das geduldige, wortlose Ausharren vor<br />

Ihm.<br />

Gregorian Chant<br />

“Cantare amantis est - Singing belongs to him, who loves“. (St Augustine)<br />

The Gregorian chant is one of Christendom’ s oldest musical traditions, dating back to<br />

the 8th century. It expresses the message of the Holy Gospel and our faith in a unique<br />

way. This is the reason why we have cultivated the Gregorian chant from the beginnings<br />

of our monastic history up to today and why we sing it in Latin during our Divine office<br />

and High Mass.<br />

The Gregorian chant is an integral part of our spiritual life. The Gregorian liturgy pervades<br />

and sustains our everyday life. It draws us inexorably, and ever anew, into the<br />

Holy Gospel, which is the centre of our faith. The composers have managed to set key<br />

quotations from the Holy Gospel to music and thus combine words and melody in a<br />

uniquely harmonious way. Whenever we sing these hyms we open ourselves to God’s<br />

word. We focus our attention on Him again and again. Singing unto Him enables us to<br />

lay before God praise and thanksgiving, plea and grievance, joys, concerns as well as<br />

sorrows. All facets of human life are lain before God by singing unto Him.<br />

Almost without noticing it we experience the truth of St Augustine’s words: Cantare<br />

amantis est. “Singing belongs to Him who loves“. The singing gives meaning to all prayer,<br />

every form of meditation, contemplation. It means total commitment, which is pure<br />

and loving, and abides and and unites with God. Sometimes it also takes the form of patient<br />

and wordless perseverance before Him.

Beuroner Kunst<br />

Die als „Beuroner Kunst“ bezeichnete Gesamtgestaltung kultisch/liturgischer Räume ist hervorgegangen<br />

aus der gegenseitigen Befruchtung des 1863 in Beuron neugegründeten benediktinischen<br />

Reformklosters und einer Künstlergruppe um Desiderius Peter Lenz (1832-1928).<br />

Die Begegnung mit der altägyptischen Kunst bestärkte Lenz in seinem Streben nach Überwindung<br />

der gefühlvollen Kunst des Historismus und Naturalismus hin zu einer objektiven christlichen<br />

Kunst, die überzeitlich gültige religiöse Wahrheiten ausdrücken sollte. So entstand die<br />

„Beuroner Kunstschule“, die sich als dienende Kunst und als Beitrag zu einem Gesamtkunstwerk<br />

Liturgie verstand: Architektur, Wandmalereien und beuronisches Mobiliar (Altäre, Tabernakel,<br />

Chorgestühle, Bänke) korrespondierten im liturgischen Geschehen mit entsprechender<br />

liturgischer Kleidung, Büchern und anderen im Gottesdienst verwendeten Gegenständen<br />

(Weihwasserbehälter, Leuchter u.ä.). Der Anspruch der „Beuroner Kunstschule“ war es, die<br />

Christliche Kunst zu reformieren und durch die Rückkehr zu den Wurzeln der Gotteserfahrung<br />

der „Alten“ den Lebensraum für die Erneuerung des Mönchtums und der Liturgie zu schaffen.<br />

Sie will – wie die gesungene Liturgie – zur Betrachtung und zur Versenkung in Wesen und Geheimnis<br />

Gottes einladen. Architektur und Malerei strahlen eine unwandelbare Ruhe und Majestät<br />

aus. Die Abstraktion von allem Bewegten ist bis ins Letzte ausgeführt: in der Architektur<br />

bestimmen die geraden Linien das Bild; in der Malerei herrscht das Stilistische und Stilisierte<br />

vor; die Farbgebung ist harmonisch und einheitlich. Es gibt wohl kaum eine Kunstrichtung, die<br />

das Ruhen in Gott, jenen Grundzug mystischer Beschauung, klarer zum Ausdruck bringt als die<br />

„Beuroner Kunst“.<br />

Beuronese Art<br />

In 1863 the foundation of a Benedictine reform monastery near Beuron on the river<br />

Danube in Southern Germany provided an ideal opportunity for the artist monk Father<br />

Desiderius Peter Lenz (1832 – 1928) - together with two artist monks from the Beuron<br />

School of Art- to realize a comprehensive project to integrate their new form of painting<br />

into ritualistic / liturgical architecture.<br />

Father Lenz’s interest in ancient Egyptian art reinforced his determination to escape the<br />

emotional art of historicism and naturalism and turn to a genuinely Christian form of<br />

art to express eternal religious truths. So the Beuron School of Art was born. The artists<br />

saw themselves as guarantors of an applied sacral art and artists who were contributing<br />

in their own way to a synthesis of liturgical art. Here architecture, murals and Beuronese<br />

furnishings (altars, tabernacles, choir stalls, pews etc.) correspond to matching liturgical<br />

vestments, books as well as vessels (stoups or candle sticks etc. that are used during the<br />

service). It was the most ambitious and sophisticated aim of the Beuron Art School to<br />

try to reform Christian art by returning to the roots of the perception of divine Christian<br />

nature as experienced by our elders and create a living space for the renewal of monasticism<br />

and liturgy. In this sense Beuronese art - just as the chants in liturgy - strives to<br />

embrace and comprehend God’s nature and His mystery. Both the architecture and the<br />

painting transmit an unwavering tranquility and majesty. All motion is abstracted consistently,<br />

to the last detail. In the architecture we find a dominance of straight lines, in<br />

the paintings the strictly stylistic and stylized forms. The choice of colour is harmonious<br />

and uniform. Beuronese art is almost unique in the clarity with which it reveals the resting<br />

in God, this essential feature of mystical contemplation.

Kreuzgang<br />

„Man soll der Schweigsamkeit zuliebe bisweilen sogar auf gute Gespräche verzichten. Umso<br />

mehr müssen wir von bösen Worten lassen. Mag es sich also um noch so gute, heilige und aufbauende<br />

Gespräche handeln, vollkommenen Jüngern werde nur selten das Reden erlaubt wegen<br />

der Bedeutung der Schweigsamkeit. Steht doch geschrieben: ‚Beim vielen Reden wirst du<br />

der Sünde nicht entgehen‘, und an anderer Stelle: ‚Tod und Leben stehen in der Macht der Zunge.‘<br />

Denn Reden und Lehren kommen dem Meister zu, Schweigen und Hören dem Jünger.“<br />

(Benediktsregel Kap. 6, 3-6).<br />

Die Kreuzgänge eines Klosters sind Räume der Stille, der Sammlung und des Gebets. Die<br />

schlichte Schönheit dieser hohen und lichtdurchfluteten Räume atmet Weite und dient der<br />

Konzentration auf das Wesentliche. Die langen Kreuzgänge unserer Abtei gruppieren sich um<br />

zwei Innengärten – den Kreuzgarten und den Mariengarten.<br />

Im Ost-Kreuzgang vor der Türe zum Nonnenchor versammelt sich die Gemeinschaft vor dem<br />

morgendlichen Hochamt und vor der abendlichen Vesper zu einer kurzen „Statio“ (stillem Verweilen<br />

zur Vorbereitung auf die Liturgie), um dann paarweise in den Nonnenchor einzuziehen.<br />

Vom Kreuzgang im Erdgeschoss aus erreicht man die sog. „Regulären Räume“ des Klosters:<br />

Chor, Skriptorium, Oratorium, Kapitelsaal, Refektorium, Bibliothek, Konventzimmer, die dem<br />

Konvent als Gemeinschaftsräume dienen.<br />

The Cloisters<br />

“Therefore, since the spirit of silence is so important, permission to speak should rarely<br />

be granted even to perfect disciples, even though it be for good, holy edifying conversation;<br />

for it is written, ‘In much speaking you will not escape sin‘ (Prov. 10:19), and in<br />

another place, ‚Death and life are in the power of the tongue‘ (Prov. 18:21). For speaking<br />

and teaching belong to the mistress, the disciple‘s part is to be silent and to listen.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 6, 3-6)<br />

Monastic cloisters are places of silence, of contemplation and prayer. The plain beauty of<br />

these high, suffused rooms conveys breadth and fosters concentration on what is essential.<br />

The long cloisters of our abbey encompass two inner gardens – the socalled “cross-garden”<br />

– a garden laid out as a cross - and St Mary`s garden.<br />

The convent rooms of a monastery are areas of silence, contemplation and prayer.<br />

The Eastern part of the cloister, in front of the door to the nuns’ choir, is where the community<br />

assembles briefly before Mass in the morning and before Vespers in the evening.<br />

This tradition is called “statio“, a silent pause in preparation for the coming liturgy before<br />

they move into the nuns` choir in pairs.<br />

From the cloister on the ground floor you reach the so called “regular rooms“of the monastery:<br />

choir, scriptorium, oratory, chapter chamber, refectory, library and the convent’s<br />

common room which the community uses for regular or less formal meetings.

Refektorium – der Speisesaal<br />

„Beim Tisch darf die Lesung nicht fehlen ... Es soll tiefstes Schweigen herrschen, so dass man<br />

kein Flüstern und keine Stimme hört außer der Stimme des Lesers allein. Was beim Essen und<br />

Trinken benötigt wird, reichen sie sich gegenseitig, so dass keiner um etwas zu bitten braucht.“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Kap. 38,1.6)<br />

„Jeder hat seine Gnadengabe von Gott, der eine so, der andere so. Deshalb bestimmen wir nur<br />

mit einigen Bedenken das Maß der Nahrung für andere.“ (Benediktsregel, Kap. 40,1.2)<br />

„Beim Essen muss vor allem Unmäßigkeit vermieden werden; und nie darf sich Übersättigung<br />

einschleichen. Denn nichts steht so im Gegensatz zu einem Christen wie Unmäßigkeit, sagt<br />

doch der Herr: ‚Nehmt euch in acht, dass nicht Unmäßigkeit euer Herz belaste‘.“ (Benediktsregel,<br />

Kap. 39,7-9)<br />

Das Refektorium (von lat. refectio = Erfrischung) ist der Speiseraum der klösterlichen Gemeinschaft.<br />

Es ist mehr als ein bloßer Speisesaal. Hier wird die Feier des Abendmahls im Gottesdienst<br />

in den Alltag hinein fortgesetzt.<br />

Nach dem Mittagsgebet und nach der Vesper zieht der Konvent ins Refektorium, um die<br />

Hauptmahlzeiten einzunehmen. Das Refektorium gehört zu den „Regulären Räumen“ des<br />

Klosters, in denen das Schweigen beobachtet wird.<br />

Die Mahlzeiten werden in Stille eingenommen; eine Tischleserin liest mittags zunächst einen<br />

Abschnitt aus der Heiligen Schrift und abends einen aus der Benediktsregel vor. Danach werden<br />

die aktuellen Radionachrichten eingespielt sowie aus Zeitungen oder fortlaufend aus einem<br />

Buch gelesen. An Festtagen hört der Konvent bei Tisch klassische Musik.<br />

The Refectory<br />

“The meals of the sisters should not be without reading ... And let absolute silence be<br />

kept at table, so that no whispering may be heard nor any voice except the reader‘s.<br />

As to the things they need while they eat and drink, let the sisters pass them to one<br />

another so that no one need ask for anything.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 38, 1.6)<br />

“Everyone has her own gift from God, one in this way and another in that (1 Cor. 7:7).<br />

It is therefore with some misgiving that we regulate the measure of others‘ sustenance.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 40, 1.2)<br />

“Above all things, however, over-indulgence must be avoided and a monk must never be<br />

overtaken by indigestion; for there is nothing so opposed to the Christian character<br />

as over-indulgence according to Our Lord‘s words, ‘See to it that your hearts be not burdened<br />

with over-indulgence‘ (Luke 21:34).“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 39, 7-9)<br />

The refectory (Latin “refectio”: refreshment) is the dining-room of a monastic community.<br />

But it is more than that. It is where the celebration of the Eucharist is sort of continued<br />

and transferred to everyday life. After our midday prayer and after Vespers the Sisters<br />

take up their seats in the refectory for their main meals. The refectory is a part of the<br />

convent’s regular rooms where silence is obeyed. So the meals are taken in silence. At<br />

lunchtime the Sister responsible for the readings first reads out a passage from the Holy<br />

Scriptures. In the evening it is a chapter from the Rule of St Benedict. After the spiritual<br />

readings the Sisters either listen to the latest radio news, newspaper reports or another<br />

chapter of a book. On feast days the community listen to classical music.

Gelübde / Ewige Profess<br />

„Höre, mein Sohn, meine Tochter, auf die Weisung des Meisters … und erfülle sie durch die Tat!“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Prolog 1)<br />

„In Gegenwart aller verspreche sie Beständigkeit, klösterlichen Lebenswandel und Gehorsam.“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Kap. 58,17)<br />

„Höre“, so lautet das erste Wort der Benediktsregel. Es ist eine Einladung, ganz Ohr zu sein<br />

und das „Ohr seines Herzens“ zu neigen. Das heißt konkret: offene Ohren zu haben für den Anruf<br />

Gottes, für die Sorgen und Anliegen der Menschen, und bereit zu sein, auf das Gehörte mit<br />

unserem Leben zu antworten. Gerade diese Beziehung zwischen Hören und Antworten kennzeichnet<br />

das benediktinische Ordensleben.<br />

In der Ewigen Profess, der öffentlichen Ablegung der Gelübde und der endgültigen Aufnahme<br />

in die Klostergemeinschaft, verspricht die Professe daher den Gehorsam, d.h. sie will ihr Leben<br />

ganz dem Dienst an Gott und den Menschen weihen. Im Versprechen der stabilitas (Beständigkeit),<br />

der Bindung an diese Gemeinschaft und den einmal gewählten Ort, kommt zum Ausdruck,<br />

dass sie Gott in allem suchen und ihm in den Höhen und Tiefen des Lebens stets treu<br />

bleiben möchte. Das dritte Versprechen bekennt sich zu einem Leben in Dynamik: conversatio<br />

morum (klösterlicher Lebenswandel) bedeutet beständiges Bemühen um ein Leben nach dem<br />

Evangelium sowie stete Erneuerung und Wachstumsbereitschaft.<br />

In der Profess versprechen wir also, ein Leben lang zu hören, zu lernen und auf diesem Weg nie<br />

stehen zu bleiben. Im Vertrauen auf Gottes Führung und sein treues Geleit bringen wir im Professgesang<br />

unsere Hoffnung zum Klingen: „Nimm mich auf, Herr, nach deinem Wort, und ich<br />

werde leben“ (Psalm 119,116).<br />

Vows / Eternal Profession<br />

“Listen carefully, my child, to your master‘s precepts, and incline the ear of your heart.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Prol 1)<br />

“She promises before all in the oratory stability, fidelity to monastic life and obedience.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch58, 17)<br />

“Listen“. This is the first word of the Rule of St Benedict. It is an invitation to be all ears<br />

and to bow to the “ear of his/her heart“. Specifically, this means: open up your ears for<br />

God`s call, for the sorrows and concerns of fellow human beings and to be prepared to<br />

respond to the things you have experienced in our own life. It is precisely this relationship<br />

between listening and responding which signifies life according to the Rule of<br />

St Benedict.<br />

So in the eternal profession, a public vow which means final acceptance into the monastic<br />

community, the nun professes obedience. This means that she is willing to dedicate<br />

her whole life entirely to the service of God and her fellow human beings. Her promise<br />

of stability (persistence), her commitment to this community and the place she has<br />

chosen, mean that she will seek God everywhere and in everything and that she wishes<br />

to always be faithful to Him in all the vicissitudes of life. The third promise refers to a<br />

dynamic life: conversatio morum (monastic conduct of life) and it entails the constant<br />

endeavour to lead a life according to the Holy Gospel, along with constant personal renewal<br />

and propensity for mental development.<br />

So with our profession we promise never to stop listening, learning or following our<br />

chosen paths. In trusting God’s guidance and His faithful assistance we express our<br />

hope by singing: “Accept me, oh Lord, according to Thy will and I will live“. (Psalm<br />

119,116) This Psalm is the text of the chant during our profession ceremony.

Zelle<br />

„Bleibe in deiner Zelle und sie wird dich alles lehren.“ (Wort des Altvaters Moses)<br />

„Wir glauben, dass Gott überall gegenwärtig ist.“ (Benediktsregel, Kap. 19,1)<br />

Einsamkeit und gemeinschaftliches Leben gehören im klösterlichen Leben untrennbar zusammen.<br />

Sie befruchten sich gegenseitig. Die Zelle, von lat. cella = Raum, Kammer, innerstes Heiligtum<br />

eines Tempels, ist der persönliche Wohn- und Schlafraum einer Schwester und wird als<br />

geschützter Lebensraum und als Ort des Rückzugs von allen geachtet. Die Zelle ist ein bevorzugter<br />

Ort des Alleinseins, eine Stätte, in der jede unter den Augen Gottes ganz bei sich selbst<br />

zu Hause sein kann. Hier öffnet sich der Raum für das persönliche Gebet, für die Meditation<br />

und für die geistliche Lesung.<br />

„Das Gebet soll kurz und rein sein … wir sollen wissen, dass wir nicht durch die vielen Worte,<br />

sondern durch die Reinheit des Herzens und die Tränen der Reue Erhörung finden.“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Kap. 20, 3.4.)<br />

Die Zelle ist der klösterlichen Lebensweise entsprechend einfach eingerichtet mit Bett, Tisch,<br />

Stuhl, Schrank und einem Regal. Der Spielraum für eine individuelle Gestaltung ist begrenzt,<br />

aber dennoch ist die Zelle der unverwechselbare persönliche Lebensbereich jeder Schwester.<br />

The Cell<br />

“Remain in your cell and it will teach you everything.“ (Father Moses)<br />

“We believe that the divine presence is everywhere.“ (Rule of St Benedict, Ch 19, 1)<br />

Solitude and community life are inseparably intertwined in monastic life. They reinforce<br />

each other. The cell, derived from Latin cella = room, chamber, the innermost sacredness<br />

of a temple, is respected by every convent Sister as a protected living space and retreat.<br />

The cell is the preferred place of solitude, a sanctuary, where everyone can feel to be<br />

herself before the eyes of God. Here the space opens up for personal prayer, for meditation<br />

and for spiritual reading.<br />

“Our prayer, therefore, ought to be short and pure, And let us be assured that it is not<br />

in saying a great deal that we shall be heard (Matt 6:7), but in purity of heart and in<br />

tears of compunction.” (Rule of St Benedict, Ch 20, 3.4.)<br />

As befits monastic life, the cell is sparcely furnished with a bed, a table, a chair and a<br />

shelf. The scope for an individual layout is limited. Yet the cell is a distinctive personal<br />

area of life for every sister.

Klosterpforte / Klausurtür<br />

„Alle Fremden, die kommen, sollen aufgenommen werden wie Christus; denn er wird sagen:<br />

‚Ich war fremd, und ihr habt mich aufgenommen.‘ Allen erweise man die angemessene Ehre,<br />

besonders den Brüdern im Glauben und den Pilgern. Sobald ein Gast gemeldet wird, sollen ihm<br />

daher der Obere und die Brüder voll dienstbereiter Liebe entgegeneilen. Zuerst sollen sie miteinander<br />

beten und dann als Zeichen der Gemeinschaft den Friedenskuss austauschen.“<br />

(Benediktsregel, Kap. 53, 1-3)<br />

Besucher sind in unserem Kloster jederzeit willkommen. Wir freuen uns, Menschen zu begegnen<br />

und mit ihnen unsere Freude am Leben und am Glauben zu teilen.<br />

Wer als Gast unser Kloster besuchen oder an einem unserer Kurse und Seminare teilnehmen<br />

möchte, meldet sich zunächst an der Klosterpforte bei unseren Gastschwestern. Die Gäste<br />

wohnen im Gästehaus außerhalb der Klausur, haben ein eigenes Refektorium und nehmen,<br />

sofern sie dies möchten, in der Kirche am Stundengebet teil.<br />

Das Innere des klösterlichen Lebensbereiches erreicht man durch die Klausurtüre. Sie ist in der<br />

Regel verschlossen und markiert den privaten Lebensbereich der klösterlichen Gemeinschaft.<br />

Wer neu ins Kloster eintritt, gelangt durch diese Tür hinein. Auch bei besonderen Anlässen benutzt<br />

der Konvent diese Tür, z.B. bei feierlichen Einzügen in die Kirche an Weihnachten und<br />

Ostern sowie am Fest der heiligen Hildegard am 17. September.<br />

Monastic Hospitality<br />

“Let all guests who arrive be received like Christ, for He is going to say, ‘I came as a<br />

guest, and you received Me‘ (Mtt. 25:35). And to all let due honor be shown, especially<br />

to the domestics of the faith and to pilgrims. ‘As soon as a guest is announced, therefore,<br />

let the Superior and the brethren meet him with all charitable service. And first of all<br />

let them pray together, and then exchange the kiss of peace‘.“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Ch 53, 1-3)<br />

Visitors are always welcome in our monastery. We are happy to meet people and share<br />

with them our joy in life and faith.<br />

Anyone who wishes to visit our monastery or participate in our courses and seminars<br />

should first contact the Sisters responsible for our guest accomodation at the convent<br />

gates. Guests are accommodated outside the enclosure. They have their own refectory<br />

and can participate in the hourly prayers if they so wish.<br />

You reach the interior of the monastic living area through a special door leading into<br />

the enclosure. It is normally closed and marks the absolutely private area of the monastic<br />

community.<br />

Everyone who joins our order is admitted and welcomed there.<br />

The whole community also assembles in front of this door on feast days such as Christmas<br />

or Easter as well as on 17th September, the feast day of our patron saint, St Hildegard.

Hören und Schweigen<br />

„Höre, mein Sohn, [meine Tochter], auf die Lehren des Meisters, neige das Ohr deines Herzens …<br />

und erfülle sie durch die Tat“ (Benediktsregel, Prolog 1)<br />

Hören ist das Grundwort benediktinischen Lebens. Der Glaube kommt vom Hören. Er ist Antwort<br />

auf das Wort und den Anruf Gottes. Der heilige Benedikt beginnt seine Ordensregel mit<br />

dem Wort „Höre“. Bereit sein zu hören ist für ihn die Lebensaufgabe eines Menschen, der auf<br />

der Suche nach Gott und nach dem Sinn seines Lebens ist.<br />

Hören kann jedoch nur der, der auch schweigen kann, der den Lärm von außen und den Lärm<br />

im eigenen Herzen zur Ruhe bringen kann. Deshalb gibt es im Kloster Zeiten und Orte, in denen<br />

nicht gesprochen und der Stille Raum gegeben wird: zwischen dem Nachtgebet am Abend<br />

und der morgendlichen Heiligen Messe z.B., oder in den Kreuzgängen und im Refektorium.<br />

Deshalb auch bemühen wir uns um einen maßvollen und zielgerichteten Gebrauch von Computer,<br />

Internet, E-Mail und Handy.<br />

Das Schweigen dient der Sammlung und Konzentration. Es verhindert die bloße Zerstreuung.<br />

Nur aus dem Schweigen heraus können wir lernen, im Wirrwarr der Stimmen auf das Wesentliche<br />

zu hören. Früchte des Schweigens sind innere Ruhe und Sammlung, aber auch echte Begegnung.<br />

Insofern hat auch die Kultur des Redens und der Sprache ihren Urgrund im Schweigen.<br />

Erst aus dem Schweigen und dem Hören heraus erwachsen gute Gespräche, ein ganz<br />

neues Verstehen, die Feinheit des Gefühls und die Fähigkeit des Mitschwingens, die die Fremdheit<br />

zwischen den Menschen überbrücken kann.<br />

Listening and Being silent<br />

“Listen carefully, my child, to your master‘s precepts, and incline the ear of your heart<br />

(Prov. 4:20). Receive willingly and carry out effectively …“<br />

(Rule of St Benedict, Prol 1)<br />

Listening is fundamental to the Benedictine life. Faith comes from listening. It is the response<br />

to the word and the call of God. St Benedict opens the rules for his order with the<br />

word “listen“. For him being prepared to listen is the lifelong task of any human being<br />

who seeks God and the meaning of life.<br />

Only someone who is capable of silence can block the noise from both outside and inside<br />

of her / his heart so as to find peace and quiet. This is why a monastery makes sure<br />

that there are times – between the nightly prayers and morning Mass - and places - within<br />

the cloisters and in the refectory - where talking is forbidden and silence must be<br />

preserved. This is why we also aim for a moderate and purposeful use of computers, Internet,<br />

Email and mobile phones.<br />

Silence is an aid to contemplation and concentration. It prevents distraction. Only silence<br />

permits us to learn, to listen to what is essential.<br />

The benefits of silence foster inner quiet and contemplation but also genuine encounters.<br />

In this respect, the culture of speech as well as language lie at the heart of being<br />

silent and provide the reason. Profound conversations and listening to people grow<br />

out of silence and offer a completely new understanding, a particular sensitivity and<br />

an ability to show compassion which can bridge the alienation between fellow human<br />

beings.

Noviziat<br />

„Wer ist der Mensch, der das Leben liebt und gute Tage zu sehen wünscht? Wenn du das hörst<br />

und antwortest: ‚Ich‘ …“ (Benediktsregel, Prolog 15).<br />

„Man achte sorgfältig darauf, ob der Novize wirklich Gott sucht.“ (Benediktsregel, Kap. 58, 7)<br />

Benediktinerin zu werden, ist ein lebenslanger Weg, das eigene Leben als Christ bewusst und<br />

konkret zu gestalten. Am Beginn stehen das Kennenlernen eines Klosters, Gespräche und verschiedene<br />

Aufenthalte im Gästehaus. Wächst und reift der Wunsch, ein Leben nach der Regel<br />

Benedikts führen zu wollen, dann kann der Eintritt in die Gemeinschaft folgen. Mit dem Eintritt<br />

beginnt das sogenannte Postulat, eine Zeit des Einlebens in den Rhythmus des klösterlichen<br />

Alltags und der Prüfung der eigenen Berufung.<br />

Nach ca. 6-12 Monaten erfolgt mit der Einkleidung die Aufnahme in das Noviziat. Die neue<br />

Mitschwester erhält einen Ordensnamen und das Ordenskleid. Das Noviziat bietet die Möglichkeit,<br />

sich tiefer mit der neuen Lebensform auseinanderzusetzen und in ein geistliches Leben<br />

hineinzuwachsen. Auf diesem Weg ist die Novizenmeisterin eine wichtige Hilfe und Stütze.<br />

Neben der Mitarbeit in verschiedenen klösterlichen Arbeitsbereichen, gewährt das Noviziat<br />

u.a. eine intensive Einführung in die Regel Benedikts, in die klösterliche Spiritualität, in den<br />

Gregorianischen Choral und in das Gebet.<br />

Nach zwei Jahren Noviziat kann die Novizin darum bitten, sich für drei Jahre an die Gemeinschaft<br />

und das Leben nach der Regel des heiligen Benedikt zu binden. Wenn die Gemeinschaft<br />

ihrerseits der Bitte zustimmt, kann die Novizin ihre zeitliche Profess ablegen. Nach Ablauf dieser<br />

drei Jahre folgt in der Regel die ewige Profess.<br />

The Novitiate<br />

“Who is the one who will have life, and desires to see good days? And if, hearing Him,<br />

you answer, ‘I am the one‘ …“ (Rule of St Benedict, Prol 15)<br />

“Let her examine whether the novice is truly seeking God.“ (Rule of St Benedict, Ch 58, 7)<br />

Becoming a Benedictine nun is a lifelong way of shaping one`s own life as a Christian,<br />

consciously and concretely. In the beginning the main thing is to familiarize yourself<br />

with life in the monastery. You have to attend certain talks and discussions, and stay a<br />

number of times in the guest quarters. In the event that the desire to lead a life according<br />

to the Rule of St Benedict grows and matures entry into the community can follow.<br />

The entry marks the beginning of what is called the postulancy, a time of adjusting to<br />

the rhythm of everyday monastic life and considering one`s own calling.<br />

After some six to twelve months the acceptance into the novitiate is followed by the<br />

clothing. The novice receives a monastic name of her own choice and a habit. The novitiate<br />

offers the opportunity to adapt to the new way of life and to grow into the spiritual<br />

life of the convent.<br />

The mistress of the novices provides important help and support. Novices participate in<br />

various monastic fields of work. But the novitiate also provides amongst other things<br />

an intensive introduction into the Rule of St Benedict, into monastic spirituality, into the<br />

Gregorian chant and into prayer.<br />

After another two years the novice can officially request to be allowed to commit herself<br />

to the community and to a life according to the Rule of St Benedict for another period<br />

of three years. If the community gives its consent the novice can take her temporary<br />

vows. For most, the solemn, eternal vows come at the end of these three years.