hildegard_english_final

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

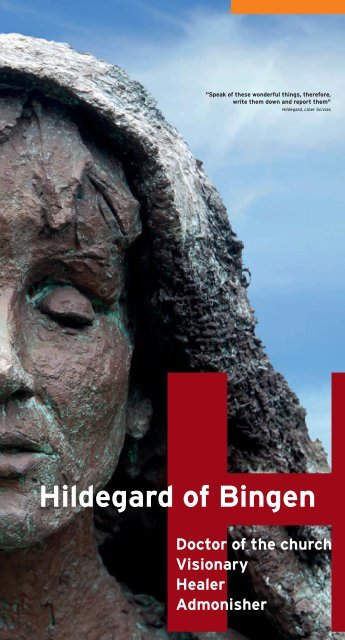

"Speak of these wonderful things, therefore,<br />

write them down and report them"<br />

Hildegard, Liber Scivias<br />

Hildegard of Bingen<br />

Doctor of the church<br />

Visionary<br />

Healer<br />

Admonisher

Biography<br />

For me Hildegard is a strong, prophetic figure –<br />

a window to heaven, to transcendence. She<br />

teaches us that the love of God, love of creation,<br />

love of humankind and love of the Church belong<br />

together. Hildegard’s criticism was always<br />

constructive, it was rooted in her love of the<br />

Church and helped to build up the Church. Her<br />

passionate dedication urges all Christians,<br />

clergy and religious to be credible. Saint<br />

Hildegard is a mentor and companion for me.<br />

Clementia Killewald OSB<br />

Abbess, Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

1098<br />

ca. 1106<br />

1112<br />

1136<br />

1141–1151<br />

1147/1148<br />

1150<br />

1147–1179<br />

1158<br />

1158–1170/1<br />

1158–1173<br />

1163<br />

1165<br />

1173<br />

1174/1175<br />

1178/1179<br />

1179<br />

1180–1190<br />

1227<br />

1632<br />

1802<br />

1904<br />

2012<br />

Hildegard is born in Rhine-Hesse (region<br />

southwest of Mainz)<br />

Hildegard is placed in Jutta of Sponheim’s care<br />

for education<br />

Hildegard enters an enclosed cell at<br />

Disibodenberg<br />

Death of Jutta of Sponheim<br />

Hildegard is elected Magistra<br />

Work on her first book, Liber Scivias,<br />

composition of songs and a musical drama<br />

Pope Eugene III confirms Hildegard’s visionary<br />

gift<br />

Move to the new monastery at Rupertsberg<br />

near Bingen<br />

Extensive correspondence with popes, bishops<br />

...<br />

Deed of ownership of Rupertsberg<br />

Public preaching at Mainz, Trier, Cologne and<br />

other places<br />

Work on her books Liber Vitae Meritorum,<br />

Physica and Causae et Curae and Liber<br />

Divinorum Operum<br />

Meeting with the Emperor Frederick<br />

Barbarossa at Ingelheim<br />

Hildegard founds a second monastery at<br />

Eibingen, of which she is also abbess.<br />

Hildegard’s secretary Volmar dies<br />

The monk Godfrey begins to write the Life of<br />

Hildegard<br />

Hildegard comes into conflict with the<br />

diocesan administrators of Mainz<br />

Hildegard dies on 17 September<br />

The monk Theodoric completes the Life of<br />

Hildegard<br />

First petition for her canonization<br />

The monastery at Rupertsberg is destroyed<br />

during the Thirty Years’ War<br />

Dissolution of the monastery at Eibingen<br />

during the Secularization<br />

The Abbey of St Hildegard is newly founded<br />

Canonization and Proclamation of Hildegard of<br />

Bingen as a Doctor of the Church

The Twelfth Century<br />

Hildegard was born at a time of upheaval and far-reaching<br />

changes. The climate was warming, the population<br />

increased. New arable land was claimed, rural settlements<br />

and towns develop. People became more mobile. New<br />

methods in agriculture and specialisation in craftsmanship<br />

and trade facilitate the better provision of people. Goods<br />

were transported over long distances. The guilds, a new<br />

form of society, came into existence. The use of coinage<br />

gradually replaces barter. Written documentation in<br />

everyday life attains a higher significance.<br />

The cultural life of this era is characterized by the flowering<br />

of Romanesque art with the Gothic period beginning in<br />

France. First universities are founded in Paris and Bologna<br />

at an age when providing access to higher education is still<br />

the privilege of monasteries. The crusades accelerate the<br />

encounter of different cultures. Writings in Greek and<br />

Arabic (for instance on philosophical and medical subjects)<br />

reach the Western world.<br />

For me Hildegard of Bingen is a woman, who was<br />

able to realize her talents and bring them to<br />

fruition in a very special way, which in her day<br />

required tremendous courage and profound faith in<br />

God, but also confidence in herself. Were she alive<br />

today, she might perhaps be a brilliant scientist or<br />

a Mother Teresa. In her, both came together. Her<br />

inquisitiveness about the world that surrounded<br />

her and which she wanted to understand, as well as<br />

her dedication to the infirm and those in need. She<br />

rejoiced in God’s creation, but was stern with those<br />

who would not respect and honour it.<br />

Margarethe von Trotta<br />

The Church, too, is undergoing change. In 1054 Rome and<br />

Byzantium seperate. Christendom is now divided into a<br />

Western and an Eastern Church. The Investiture<br />

Controversy rages between pope and emperor over the<br />

right to appoint bishops. The first crusade sets off for the<br />

Holy Land in 1096. Deplorable internal conditions (simony,<br />

married clergy, moral decline and excessive wealth) present<br />

a threat to the Church. This leads to a change of thought in<br />

the Church and a desire for reform: the Gregorian Reform,<br />

the foundation of new orders, itinerant preachers, the sect<br />

of the Cathars are all reactions to the condition of the<br />

Church.<br />

When she was about 14, Hildegard‘s parents<br />

committed her to the monastic life. Hard though<br />

this is to imagine today, in Hildegard’s time this<br />

was a privilege. To be able to enter a monastery<br />

was an opportunity open to a select few – most<br />

often members of the nobility. – Only life in a<br />

monastery offered the possibility of an excellent<br />

education and continued training.

The Sites<br />

The canonization of Hildegard of Bingen is a<br />

significant development for the Universal Church. I<br />

am delighted that this outstanding person, who is<br />

already held in high esteem in our country, has now<br />

received further recognition. The Abbey of St<br />

Hildegard at Eibingen has become an important<br />

place of pilgrimage and a Hildegard Centre in<br />

Germany. I am grateful that the veneration of St<br />

Hildegard in the Benedictine Order, at the Abbey of<br />

St Hildegard and in the dioceses of Mainz, Trier and<br />

Limburg bears such abundant fruit.<br />

Robert Zollitsch<br />

Archbishop em. of Freiburg<br />

Disibodenberg<br />

Hildegard began her life at Disibodenberg<br />

on 1 November 1112. The women in the<br />

hermitage followed a strict monastic life<br />

according to the Rule of Saint Benedict.<br />

Hildegard received a well-founded, broad monastic education<br />

from her mentor, Jutta of Sponheim: She learned to read, write<br />

and sing, acquired comprehensive knowledge of the Scriptures,<br />

but also closely studied nature, in particular herbs and plants.<br />

At Disibodenberg she wrote her first book, Liber Scivias. In<br />

1147/48 Pope Eugene III was residing at Trier and heard about<br />

Hildegard. He had her visionary gift examined by a commission<br />

and confirmed it.<br />

In a letter he bade her continue with her writing. For Hildegard<br />

this was endorsement, encouragement and stimulation. For<br />

those around her it was definitive proof that the Magistra of<br />

Disibodenberg really was “God’s trumpet”. While all of this was<br />

happening, Hildegard also pursued her intention of founding her<br />

own monastery.<br />

Rupertsberg<br />

Hildegard purchases land at<br />

Rupertsberg near Bingen and with her<br />

nuns built a monastery based on her<br />

own concept. They relocated between<br />

1147 and 1151. A charter in the name of Henry, archbishop of<br />

Mainz, dated 1 May 1152, documents the consecration of the<br />

church. There was a dispute with the abbot of Disibodenberg<br />

concerning Rupertsberg’s independence and its possessions.<br />

Hildegard made use of her good connections and received deeds<br />

which largely safeguard her monastery’s independence. In 1632<br />

Rupertsberg was destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War.<br />

Eibingen<br />

Hildegard’s fame drew many to seek admission at<br />

Rupertsberg. Soon the monastery was too small.<br />

She bought a vacated monastery at Eibingen. It<br />

was rededicated in 1165. Hildegard also became<br />

abbess of this second monastery and crossed the<br />

Rhine twice a week to visit the sisters at Eibingen.<br />

In 1802, as a result of the Secularization, the monastery was<br />

dissolved; all its possessions were lost. In 1831 the monastic<br />

church became the parish church of Eibingen.<br />

New Foundation of the Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

In 1904, after a four years of building, 14 nuns of the<br />

Abbey of St Gabriel in Prague move into the newly<br />

built monastery high above the Rhine. The<br />

monastery is raised to the full status of an abbey<br />

and endowed with all rights and privileges of<br />

Hildegard’s former monasteries. It is exempt<br />

from local episcopal authority and is placed<br />

directly under the jurisdiction of the Holy See.<br />

The community of the Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

regards the study of and care for Hildegard’s<br />

legacy as its pre-eminent concern, passing it<br />

on to contemporaries as a timelessly relevant<br />

message.

The Works<br />

Saint Hildegard was an eminent polymath, who left a<br />

substantial body of highly diverse work. She was a nun, but<br />

equally a scientist, a theologian and a philosopher, a musician<br />

and poet, and a physician, particularly skilled in methods of<br />

natural healing. Her whole work aims at directing people<br />

towards God and to encourage them to live a life of faith.<br />

The seven most important works of Hildegard of Bingen:<br />

Hildegard’s teaching aims at guiding humans onto<br />

the way of salvation, by showing them that out of<br />

love God has already made His way to them and<br />

continues to walk with them: At the creation,<br />

through the incarnation and throughout history. For<br />

me, therefore, it is first and foremost an intellectual<br />

challenge to grasp Hildegard’s doctrine of God, man<br />

and the world in the philosophical-theological<br />

context of the twelfth century and to make it<br />

accessible for us today. At the same time she is my<br />

mentor in the conduct of life, because she teaches<br />

me to find the right balance for myself - which is<br />

what the end leads every human being to<br />

happiness.<br />

Maura Zátonyi OSB<br />

Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

LIBER SCIVIAS – Know the Ways (1141-1151)<br />

In Hildegard’s first theological work, in which she records her<br />

visions and which spread her fame during her lifetime, she<br />

discusses on the one hand God’s way to man in creation,<br />

redemption and the course of history and on the other man’s<br />

ways to God.<br />

LIBER VITAE MERITORUM –<br />

The Book of Life’s Merits (1158-1163)<br />

The second of Hildegard’s main works reveals in dramatic<br />

dialogues between 35 virtues and vices the inseparable<br />

interrelation of the cosmos, salvation history and human moral<br />

conduct. It becomes clear that personal decisions are part of<br />

the cosmic struggle between good and evil.<br />

LIBER DIVINORUM OPERUM –<br />

The Book of Divine Works (1163-1170)<br />

Hildegard’s later work deals with the definition of the relational<br />

concept of God, the world and man. Once again her main<br />

themes and concerns are summarized in a sophisticated<br />

sweep.<br />

CAUSAE ET CURAE –<br />

Cause and Cure of Illnesses (1150-1158)<br />

In this book Hildegard describes a multitude of illnesses, their<br />

causes and symptoms and then gives instructions for<br />

treatment using natural remedies. Particular significance is<br />

ascribed to the advice on prevention of diseases and for a<br />

healthy and moderate way of life.<br />

PHYSICA – Wholesomeness of Creation – Natural and<br />

Effective Power of Things (1150-1158)<br />

This work describes in nine chapters the powers of nature and<br />

their effect on healthy and on sick people: herbs, elements,<br />

trees, gemstones, fish, birds, land animals, reptiles and metals.<br />

Time and again Hildegard emphasizes that the nature of visible<br />

things points to an invisible reality.<br />

SYMPHONIAE – Songs (1151-1170)<br />

This book contains 77 chants and songs for which Hildegard<br />

composed both the music and the words, as well as the musical<br />

drama “Ordo Virtutum” (The Dance of the Virtues), which was<br />

first performed at the consecration of the monastic church at<br />

Rupertsberg.<br />

EPISTOLAE – Letters (1147–1179)<br />

This collection of letters is comprises of some 390 of<br />

Hildegard’s letters addressed to her contemporaries, some<br />

well-known, others less well-known. Some personal but also<br />

many universally valid messages are found here. Hildegard<br />

reveals herself as an attentive witness and observer of current<br />

affairs and admonishes clergy and secular officials with a true<br />

awareness of her prophetic mission.

The Benedictine<br />

The orderly, well-balanced Benedictine rhythm of life in<br />

space, time and communal existence permeated all of<br />

Hildegard’s life. The pillars of spiritual life – prayer and work,<br />

study and spiritual reading, solitude and communal living –<br />

formed her every thought and action and was at the root of<br />

all of her work and ministry. Hildegard’s life and daily routine,<br />

like that of all nuns and monks, was defined by the Scriptures.<br />

In a monastery, liturgy regulates the course of the day;<br />

prayer times punctuate the varied tasks. This fosters<br />

composure and concentration, and helps us to view<br />

everything before God and in his gaze and to focus on the<br />

essential. In doing so, all things become connected and<br />

reciprocally interrelated.<br />

For Hildegard, the Benedictine canon of values – love of God<br />

and love of man, attentiveness and readiness to listen,<br />

reverence and hospitality, compassion and benevolence,<br />

liberty and constancy, peace and responsibility, centeredness<br />

and moderation, gratitude and humility – is the foundation on<br />

which she stands and the source from which she draws. In<br />

that sense she is a true Benedictine saint and a witness to<br />

the undiminished fascination and ever new reality of this<br />

concept of life.<br />

Saint Hildegard was profoundly shaped by<br />

Benedictine thought. From this she drew strength<br />

for her prophetic mission. In this was rooted the<br />

strength to proclaim her faith – 900 years ago, as<br />

today. For me it is a gift of God’s graces that of all<br />

the popes it was the one that bears the name of<br />

our founding father Benedict, who proclaimed<br />

Hildegard a Doctor of the Church.<br />

Edeltraud Forster OSB<br />

Abbess em., Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

The first light of day marks the devout words of apostolic<br />

teaching, but the dawn of day shows the beginning of the<br />

(monastic) way of life, which first originated in the desert<br />

and in caves; but then the sun shows the particular and<br />

well-structured way of my servant Benedict. I have infused<br />

him with a glowing fire and taught him (…) because this<br />

Benedict is like a second Moses.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Scivias<br />

Since Saint Benedict wrote his Rule in the fear of God, in<br />

charity, love and mercy, nothing must be added to it or<br />

removed from it, as it does not lack in anything, since it was<br />

written and brought to perfection by the Holy Spirit.<br />

Hildegard, Explanations on the Rule of St Benedict, II.3<br />

Edeltraud Foster OSB, Abbess em.<br />

and Clementia Killewald OSB, Abbess,<br />

the 34th and 35th successors of Saint<br />

Hildegard

The Visionary<br />

The word ‘vision’ is derived from the Latin word ‘videre’ – to<br />

see. From a biblical point of view, to see means more than<br />

just the exterior perception of reality. What is meant is a<br />

loving discernment, access to an understanding of the<br />

essential and ultimately an intuitive vision and cognizance of<br />

God. Saint Hildegard was a Benedictine and as such familiar<br />

with the Bible, which she studied daily. In prayer and<br />

contemplation she received what she herself referred to as<br />

an “understanding of the Scriptures”. In consequence, her<br />

works were above all holistic interpretations of the Scriptures<br />

in a visionary-allegorical form. What is so specific about<br />

Hildegard’s visions, which almost all begin with the words “Et<br />

vidi” (“And I saw”), can be explained in five steps:<br />

What intrinsically is a basic feature of each and<br />

every Christian – though for the most part in an<br />

unspectacular way – was most exceedingly<br />

bestowed upon the seer of the Rhine: the gift and<br />

the task not to become fixated on the beautiful<br />

and the difficult things of everyday life, not to be<br />

confined by one’s limited horizon, not to be<br />

absorbed by the major and minor demands of the<br />

here and now, but to see further than the end of<br />

one’s nose, beyond one’s own existence and to<br />

glimpse of the whole of the world and all history.<br />

Stephan Ackermann<br />

Bishop of Trier<br />

p When still a child, Hildegard was called by God in a special<br />

way and lived all of her life in a profound closeness to her<br />

creator.<br />

p In her daily study of the Scriptures, in the light of faith and<br />

on the background of her universal learnedness, the<br />

mysteries of God revealed themselves to her,<br />

p which she saw inwardly in ever new visionary images<br />

p wrote down at the behest of God<br />

p and then interpreted theologically and spiritually<br />

But the visions that I saw, I have not experienced in dreams<br />

nor was I asleep or in mental confusion, nor were they heard<br />

with the physical ears of the exterior person nor in hidden<br />

places, but I received them wide-awake and of sound mind<br />

with the eyes and ears of the inner person, in open places<br />

according to the will of God. In which way this is happening<br />

is very difficult to understand for a corporeal person.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Scivias<br />

And I have not written these things according to a<br />

contrivance of my heart or some other person, but as I have<br />

seen and heard them in a heavenly realm and received them<br />

by the veiled mysteries of God.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Scivias

The Theologian<br />

Hildegard of Bingen is the most significant female theologian<br />

and writer of Christendom before the 16th century. She is on the<br />

same level with major theological thinkers of her age. In her<br />

extensive and diverse writings Hildegard is mainly concerned<br />

with the authentic interpretation of the Scriptures. It is her<br />

utmost concern to direct humans onto the way of salvation. The<br />

relationship between God, man and the world is at the centre of<br />

her theological concept. Man as God’s creature within creation<br />

and with responsibility for it is at the very heart of her thinking<br />

and her visions. Every single person is at all times called upon to<br />

be sensitive to their responsibility before God in their lives, in<br />

their thoughts and actions.<br />

As a theologian, I am fascinated by the<br />

individuality with which Hildegard interprets the<br />

Bible. I am particularly impressed by her reading of<br />

Genesis 2: in contrast to her contemporaries, for<br />

Hildegard, the secondary creation of Eve is not a<br />

shortcoming, but an advantage for woman –<br />

because Eve, unlike Adam, for whom God needed<br />

two steps (clay and breath), is fully human from<br />

the beginning. I gladly draw inspiration from<br />

Hildegard’s creative dialogue with the Bible! As a<br />

woman with management concerns in the Catholic<br />

Church, I am fascinated by Hildegard: She<br />

realistically assessed her opportunities and<br />

limitations in a male dominated church. Hildegard<br />

was no revolutionary, but a superb strategist,<br />

tactician and politician. She knew and accepted the<br />

conventions and rules – but at the same time did<br />

not let herself be diverted.<br />

Hildegard Gosebrink<br />

Theologian and Hildegard Biographer<br />

The Father, Son and Holy Spirit cannot be separate one from<br />

the other, but are at work in unison with one accord. These<br />

three persons of the true Trinity live inseparably in the<br />

majesty of the Godhead (…) Therefore, oh man, know the One<br />

God in three persons. But in the folly of your mind, you think<br />

that God was so powerless that He would not be able to truly<br />

live in three persons, but in weariness to only exist in one. (…)<br />

But the Father is not without the Son, nor the Son without the<br />

Father, nor are the Father and the Son without the Holy Spirit,<br />

nor the Holy Spirit without them both, since these three<br />

persons are inseparable in the unity of the Godhead.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Scivias<br />

In the midst of the structure of the world there is man, because he<br />

is more powerful than the other creatures that live in it; admittedly,<br />

he is of slight stature, but he is great due to the strength of his<br />

soul. His head he turns upwards, his feet downwards and thus<br />

moves the upper and lower elements. Similarly he penetrates them<br />

with the work he does with his right and his left hand, because with<br />

the power of his inner person he has the strength to do this. Just<br />

as the size of man’s body exceeds the size of his heart, so the powers<br />

of the soul with their strength surpass<br />

man’s body. And just as man’s heart is<br />

hidden within his body, so his body is<br />

enveloped by the powers of the<br />

soul, because they span the<br />

whole earth.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Divinorum Operum

The Sage<br />

Man and his life are the focus of Hildegard’s thought and action.<br />

Out of pure love God created man in his image, a free being.<br />

Man’s response to this love consists of becoming ever better<br />

adjusted to the wise and moderate order of the cosmos in all of<br />

his actions and relationships. For Hildegard, life can only succeed<br />

if we responsibly structure the world out of reverence for God<br />

and respect for ourselves, each other and creation.<br />

But when God looked at man, he was well pleased, because he<br />

had created him after His own image and similitude so that he<br />

would proclaim all the wonderful works of God audibly with his<br />

sensible voice. That is to say, man is God’s most perfect work,<br />

because through him God is known and because God made all<br />

creatures for his sake. To him He granted with the kiss of true<br />

love that by his faculty of reason he glorifies and praises Him.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Divinorum Operum<br />

Hildegard is a larger-than-life personality, who<br />

impresses and encourages me. Although a<br />

visionary, she went her own way, keeping her<br />

feet firmly on the ground. Hildegard of<br />

Bingen’s example shows how strength of<br />

character, directness and openness to the new<br />

inspire faith in God and service to people. Her<br />

work is a source of inspiration of timeless<br />

vitality.<br />

Just as I, wisdom, ordered everything, when I walked around<br />

the circle of the heavens, so have I spoken through Solomon<br />

about the love of the creator for his creation and the creation<br />

for its creator: how the creator adorned creation when he<br />

created it because he loved it so much; and how creation<br />

received the creator’s kiss when it obeyed him, because it was<br />

obedient in everything. Creation had already received the<br />

creator’s kiss, in that God gave creation everything it needed.<br />

But I compare the love of the creator for creation and of<br />

creation for the creator with the love and faithfulness by which<br />

God joins man and woman so that offspring emanate from<br />

them just as all creation emanates from God.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Vitae Meritorum<br />

Malu Dreyer<br />

Prime Minister of Rhineland-Palatinate

The Admonisher<br />

Hildegard regarded herself as an instrument of God and<br />

continually wanted to show mankind the way to and with<br />

God. She never tired of reminding her contemporaries of<br />

God and admonishing them to return to the way of<br />

salvation. This admonition remains valid for us today as<br />

well. For Hildegard, it was all a matter of living the<br />

Christian life consistently. Everything, heaven and earth,<br />

faith and reason, the whole creation in all its facets and<br />

possibilities are for her a mirror of God’s love, they are at<br />

the same time gift and mission. No one may abdicate their<br />

responsibility.<br />

The seer becomes a teacher! A Doctor of the<br />

Church – what does that mean? Not only that she<br />

has presented the teaching of the Church, but<br />

rather that she taught the Church, that she has<br />

something to say to the Church… Nothing<br />

characterizes us more than our lack of passion for<br />

God. Precisely that characterizes the life of Saint<br />

Hildegard…Renewal of the Church – there is much<br />

talk of that these days. How can it succeed? Only<br />

by returning to the source, to the Gospel. We do<br />

not need to borrow extrinsic programmes – the<br />

gospel is programme enough. Hildegard lives,<br />

thinks, prays and writes with the Scriptures…<br />

What surprises and impresses with Hildegard is<br />

the breadth of her mind: philosophy and the study<br />

of nature, the art of healing in the sense of holistic<br />

medicine. Hildegard is not just concerned with the<br />

Church, with controversy within the Church. She is<br />

concerned with creation, with the cosmos, with the<br />

preservation of creation. As if one were reading a<br />

modern environmental paper…The environmental<br />

crisis is a crisis of mankind. Man has forgotten to<br />

whom he owes himself and the world. Whoever<br />

speaks of nature must not leave God unmentioned.<br />

As ultimately he will be perplexed by the world and<br />

will not understand himself.<br />

And I heard a loud voice which spoke to the man from the<br />

elements of the earth: We cannot walk and thus complete<br />

our way, as our lord has determined. Because humans<br />

with their bad deeds are spinning us around like a mill<br />

wheel. Therefore we reek of pestilence, and hunger for<br />

full justice.<br />

But the man answered: (…) The winds have become<br />

hoarse because of the stench, the air spews out filth,<br />

because humans do not open their mouths for integrity.<br />

Even vitality (viriditas) is withering because of the<br />

iniquitous superstition of the preposterous masses of<br />

people, who arrange everything according to their wishes<br />

and say. “Who is that Lord whom we have never seen?”<br />

And I, God, answer them: Do you not see me by day and<br />

at night? Do you not see me when you sow and when the<br />

seed is watered by rain, so that it may grow? All of<br />

creation aspires toward its creator and obviously<br />

understands that it has been created. But man is a rebel<br />

and splits his creator into many creatures.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Vitae Meritorum<br />

Franz Kamphaus<br />

Bishop em. of Limburg<br />

von

The Healer<br />

In medieval times, monasteries were also centres for<br />

treatment and healing of the sick. At Disibodenberg,<br />

Hildegard had already acquired her considerable skills in<br />

caring for the sick, and in practical and herbal medicine.<br />

Salvation and healing are inseparable for her. Humans<br />

become ill when they drop out of the originally harmonious<br />

relationship with God and the surrounding world. That is<br />

why a meaningful, value-centred and moderate way of living<br />

is the best prevention of illnesses of the body and the soul.<br />

It is not easy to approach the person of Saint<br />

Hildegard. She frequently describes herself as a<br />

simple, unlearned woman. But in reality she is one<br />

of the great women of the Middle Ages: She is a<br />

physician, composer, author of great works about<br />

the world and humanity, knows the Bible and the<br />

Church Fathers, is as well versed in the nature<br />

studies of her time, as in medicine or agriculture.<br />

Above all she was renowned for her visions. We<br />

admire this German prophet, as she may be called.<br />

Nevertheless, she will always remain unfamiliar, so<br />

that we have to make a great effort to comprehend<br />

her thought. It will be a continuing task to better<br />

understand her significance as a Doctor of the<br />

Church for our own times.<br />

Karl Kardinal Lehmann<br />

Bishop of Mainz<br />

Whilst the human body is never idle and never stops<br />

doing something, man‘s soul has, at times, on account of<br />

its nature, the duty – when tired of physical activities –<br />

to withdraw from its course, as if asleep, like a mill wheel<br />

occasionally stops working, when a rush of water has<br />

broken something at a certain point. In this way the soul<br />

is at times in silent repose, until the body is beset and<br />

aggrieved by some ill or other trepidation. Then it<br />

gathers strength and takes up its course and awakes,<br />

and it seems to that man as if he was newly born and a<br />

new person.<br />

Hildegard, Causae et Curae<br />

And the earth gave of its vitality according to the type of<br />

man, to his disposition and character and whatever the<br />

nature of his activities. That is to say, the earth reveals<br />

in useful plants, by differentiating them, the dealings of<br />

the human spirit, but shows in non-utile plants that are<br />

not usefulits negative and sinister traits.<br />

Hildegard, Physica<br />

The Hildegard-Forum<br />

herb garden at the<br />

Rochusberg in Bingen

The Mentor<br />

A total of 390 letters to popes, bishops and monasteries, to secular<br />

rulers, noblemen and ordinary people have been passed down. They<br />

are evidence of admonitory concern and great foresight, of intrepid<br />

and refreshingly humorous directness, as well as personal<br />

involvement and obvious exertion of influence in (ecclesio-) political<br />

matters. They provide an immediate insight into Hildegard’s<br />

personality and inimitably, briefly and succinctly summarize her<br />

thought and work.<br />

Oh King, it is imperative that you act cautiously. I see you in a<br />

mystic vision like a child and a recklessly living person before the<br />

Living Eyes (of God). Nonetheless you still have time to rule over<br />

worldly matters. Take care, therefore, that the heavenly king does<br />

not strike you down because of the blindness of your eyes, which do<br />

not quite see how you should hold the sceptre in your hand for<br />

proper governance. See to it that you conduct yourself in a way<br />

that the grace of God does not run dry within you.<br />

Hildegard, Epistolae, Hildegard to the Roman King Frederick (later the Emperor Barbarossa)<br />

Saint Hildegard is a major prophetic figure of the<br />

Church: vigorous, courageous and, in the truest<br />

sense of the phrase, leading the way. In her work,<br />

Hildegard has presented an all-embracing relational<br />

definition of God, world and man – and that in<br />

entirely new, figurative language. She proclaimed the<br />

faith at a time when – like the present – people had<br />

increasingly forgotten God. She lived as she taught,<br />

was credible and absolutely authentic. Her theology<br />

is ‘grounded’ and orientated toward life. In this<br />

respect especially, she proves herself genuinely<br />

Benedictine. I am convinced that with her help, it<br />

can be accomplished in our present day to once<br />

again fill people with enthusiasm for God, and for<br />

living purposeful and consistent lives of discipleship.<br />

Your tongues are silent in view of the loud voice of the sounding<br />

trumpet of the Lord. They do not love holy prudence which, like the<br />

stars, moves in a circular orbit. The trumpet of the Lord is the<br />

righteousness of God which you should ponder assiduously in<br />

holiness. (…) But that you fail to do because of your inconsiderate<br />

self-will. This is why, when you preach, the firmament of divine<br />

righteousness is lacking in luminaries, as if the stars are not<br />

shining. It is because you are night, which exhales darkness, and<br />

like an indolent people, who unwillingly do not walk in the light. (…)<br />

Instead you rather do whatever your flesh demands. (…) But you<br />

are struck down, and are no support for the Church fleeing instead<br />

to the caves of your lust, and because of your disgusting opulence,<br />

your avarice and other vanities you do not teach your subordinates,<br />

nor let them seek instruction from you (…)<br />

Hildegard, Epistolae, Hildegard to the Shepherds of the Church<br />

Philippa Rath OSB<br />

Abbey of St Hildegard

The Composer<br />

Hildegard composed 77 songs as well as a musical drama. Taken<br />

together, her musical work therefore constitutes the largest<br />

corpus of medieval music. Essentially, the songs were written<br />

for liturgical use. The core themes of Hildegard’s writings are<br />

captured again in the words and as such are a synopsis of her<br />

theological and spiritual work.<br />

For the glorifying jubilations, which ring out in the simplicity of<br />

concord and love, lead the faithful to that unity where there is<br />

no discord, because they induce in those, who still abide on<br />

earth, the sigh of heart and mouth for the heavenly reward.<br />

Hildegard, Liber Scivias<br />

Yet the body is the vestment of the soul which has a<br />

resounding voice. Therefore, it befits the body which has a<br />

voice to praise God together with the soul (…) And since man,<br />

in hearing a song, often sighs deeply when he remembers the<br />

original celestial harmony, the prophet sensitively ponders the<br />

unfathomable nature of the spirit, knowing that the soul is<br />

filled with harmony (symphonialis est) …<br />

Hildegard, Epistolae<br />

Charity abounds in all things / most excellent from the depths<br />

to high above the stars. / And it is most loving to all / for to<br />

the highest king / it has given the kiss of peace.<br />

Hildegard, Symphoniae<br />

In her songs Hildegard praises in numerous<br />

variations the mystery of God, the creation, the<br />

mystery of the incarnation and the wonders of<br />

the whole cosmos. She does this with the unique<br />

imagery of music. Her compositions are based on<br />

Gregorian Chant, those ancient melodies, which<br />

belong to the oldest musical tradition of<br />

Christianity, but take it further into totally new,<br />

undreamt of ranges. For Hildegard, the soul of<br />

man is symphonic. But in the same way, the<br />

whole of the cosmos is symphonic for her, which<br />

from the beginning has been filled with the sound<br />

of music.<br />

Oh sweetest bough, / flower of Jesse‘s root,<br />

How great is your strength, / that God looked upon the most<br />

beautiful daughter, / as the eagle looks at the sun, / because<br />

the supreme father took care of the purity of the virgin, in<br />

whom he wanted his Word to take flesh.<br />

Hildegard, Symphoniae<br />

Christiane Rath OSB<br />

Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

Listen to Hildegard music on the<br />

website of the Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

Antiphon<br />

»O aeterne Deus«<br />

Antiphon<br />

»O magne Pater«

The Saint<br />

God created man and He dwells in his soul, so that<br />

the soul is from heaven and the body is formed of<br />

the earth’s elements. The gift of creation is the<br />

sphere of my life, and it is the realm in which to<br />

experience the invisible God. As a labourer in God’s<br />

cause, I have a mission in the course of time. With<br />

God’s help, may I do good works.<br />

Saint Hildegard, teacher of the Church, pray for us,<br />

that we may be aware of our dignity and our<br />

mission - glorifying God in everything – and that<br />

we may, with His Son and the Church (His fair<br />

body), find our way home to the heart of the Father.<br />

Hiltrud Gutjahr OSB<br />

Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

Even in her lifetime, Hildegard of Bingen was revered by her<br />

contemporaries as a saint and a “prophet of the German<br />

people”. After her death on 17 September 1179, her grave<br />

became a place of pilgrimage, especially for the sick, in their<br />

hope of finding relief from pain and a cure for their illnesses.<br />

The abbess and convent of the monastery of Rupertsberg<br />

petitioned for the canonization of their founding abbess as<br />

early as 1227. Pope Gregory IX initiated the process and<br />

sent an assessment commission to Bingen, whose protocol<br />

was dispatched to Rome in 1233. As the accounts of<br />

witnesses did not meet the formal requirements, the pope<br />

charged a new commission in 1237. It is presumed that this<br />

commission never took up its work, and the canonization<br />

process came to nothing. Other initiatives were also<br />

unsuccessful, the last being those of the German Bishops’<br />

Conference in 1979 and 1987. Nonetheless, Hildegard was<br />

regarded as a saint by people far beyond the borders of<br />

Germany.<br />

After the new edition of Hildegard’s main works was<br />

completed in 2010, Pope Benedict XVI gave two catecheses<br />

on Hildegard. He acknowledged her as a “great prophet who<br />

has particular importance for our own day”.<br />

Soon afterwards, on 25 December 2010, the abbess and<br />

convent of the Abbey of St Hildegard filed another petition<br />

for the canonization of their patron, and for her designation<br />

as a Doctor of the Church. Pope Benedict XVI re-initiated<br />

the process, and recognized as miracle the fact that<br />

Hildegard had been venerated as a saint by the people for<br />

more than 850 years as a miracle. On 10 May 2012, he<br />

entered her name in the martyrology of the Universal<br />

Church. On 7 October of the same year, she was formally<br />

proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in Rome.

The Doctor of the Church<br />

In Saint Hildegard exhibits an extraordinary harmony<br />

between her teaching and everyday life.<br />

With perceptive, wise and prophetic sensitivity, Hildegard<br />

focuses on the Revelation. Her analytical study develops<br />

from the biblical event, in which, stage by stage, it remains<br />

firmly grounded. The concept of the mystic of Bingen is not<br />

restricted to tackling individual issues, it presents a<br />

synthesis of the whole of the Christian faith. That is why in<br />

her visions and subsequent reflections, she encompasses<br />

the history of salvation from the beginning of the universe<br />

to the Last Day.<br />

Hildegard’s prominent teaching reflects the teaching of the<br />

apostles, the writings of the Church Fathers and the works<br />

of the authors of her time, whilst she finds a constant point<br />

of reference in the Rule of Saint Benedict of Nursia.<br />

Monastic liturgy and the internalisation of the Scriptures<br />

constitute the guidelines of her thinking, which is centred<br />

upon the mystery of the Incarnation, and is expressed at<br />

the same time in a profound stylistic and textual uniformity,<br />

which permeates all of her writings.<br />

Excerpts from the Apostolic Letter, proclaiming Saint Hildegard of Bingen a Doctor of the Church, Pope Benedict XVI, Rome, 7<br />

October 2012<br />

Saint Hildegard of Bingen, an important<br />

female figure of the twelfth century, made her<br />

valuable contribution to the development of<br />

the Church of her time, by making the fullest<br />

use of the gifts God had bestowed upon her. In<br />

so doing, she proved herself to be a woman of<br />

lively intelligence, deep sensitivity and<br />

recognized spiritual authority. The Lord<br />

granted her a prophetic spirit and a profound<br />

ability to read the signs of the times.<br />

Hildegard exhibited a pronounced love of<br />

creation, and devoted herself to medicine,<br />

poetry and music. Above all, she always<br />

maintained a great and faithful love of Christ<br />

and for his Church.<br />

Ceremony of the<br />

proclamation of<br />

Saint Hildegard as<br />

a Doctor of the<br />

Church on 7<br />

October 2012<br />

Pope Benedict XVI on 7 October 2012

Can be purchased in our Abbey shop!<br />

Benedictine Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

Copyright:<br />

www.abtei-st-<strong>hildegard</strong>.de / www.keb.bistumlimburg.de. | www.keb.bistumlimburg.de<br />

Editor: Diocesan Educational Institution, Domplatz 3 • 60311 Frankfurt<br />

Idea and conception: Claudia Hülshörster • Eva Knoellinger-Acker • Kerstin Meinhardt • Johannes<br />

Oberbandscheid • Philippa Rath OSB<br />

Layout and realisation: Meinhardt Verlag und Agentur • © Idstein, Mai 2014<br />

Translator: Barbara Thompson<br />

Hildegard quotations are taken from the new complete (German) edition of her work.<br />

Photo and Illustration Credits:<br />

Cover: Bronze Sculpture by Karlheinz Oswald © Kerstin Meinhardt<br />

Miniatures on pages 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 13: Rupertsberg Scivias Codex, original lost in 1945: parchment,<br />

Rupertsberg monastery, c.1165-1175; hand-made facsimile, parchment, 1927-1933, Abbey of St<br />

Hildegard, Rüdesheim/Eibingen, photos: Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

p. 4: Abbey of St Hildegard © Kerstin Meinhardt<br />

Engravings: Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

p. 5: “Hildegardis”, woodcut, Schedel’s World Chronicle, Nürnberg, 1493, Nuremberg 1493<br />

p. 6: small photo: Abbey of St Hildegard, Rüdesheim/Eibingen © Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

p. 7: Ceramic Statue by Christophora Janssen OSB © Kerstin Meinhardt<br />

Miniatures on pages 9, 11, 12: Lucca Codex (Liber Divinorum Operum), parchment with 10 coloured<br />

miniatures, Rupertsberg monastery, c.1220/30, Lucca, Biblioteca Statale, Codex 1942, photo: Abbey<br />

of St Hildegard.<br />

p. 11: small photo: Herb Garden © Hildegardforum, Bingen<br />

p. 12: small photo: Hildegard and King Frederick, monastic church, Abbey of St Hildegard<br />

© Kerstin Meinhardt<br />

p. 14: Parish church and shrine of St Hildegard, Eibingen, © Kerstin Meinhardt<br />

p. 15: “S. Hildegardis Prophetissa”, monastic church, Abbey of St Hildegard © Kerstin Meinhardt<br />

photos taken on 7 October 2012: left: picture alliance/abaca; right: Jessica Kraemer<br />

The Abbey Shop<br />

Abtei St. Hildegard 1 · D-65385 Rüdesheim am Rhein<br />

Fone +49(0)6722 499-116 · klosterladen@abtei-st-<strong>hildegard</strong>.de<br />

www.abtei-st-<strong>hildegard</strong>.de<br />

Opening hours:<br />

Mondays - Fridays: from 9.30 to 11.45 a.m. and 14.00 to 17.00 p.m.<br />

Saturdays: from 9.30 a.m. to 17.00 p.m.; Sundays and public holidays:<br />

from 14.00 to 17.00 p.m.