Facing the Heat Barrier - NASA's History Office

Facing the Heat Barrier - NASA's History Office

Facing the Heat Barrier - NASA's History Office

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Facing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Heat</strong> <strong>Barrier</strong>: A <strong>History</strong> of Hypersonics<br />

Aerospaceplane<br />

“I remember when Sputnik was launched,” says Arthur Thomas, a leader in early<br />

work on scramjets at Marquardt. The date was 4 October 1957. “I was doing analysis<br />

of scramjet boosters to go into orbit. We were claiming back in those days that<br />

we could get <strong>the</strong> cost down to a hundred dollars per pound by using airbrea<strong>the</strong>rs.”<br />

He adds that “our job was to push <strong>the</strong> frontiers. We were extremely excited and<br />

optimistic that we were really on <strong>the</strong> leading edge of something that was going to<br />

be big.” 49<br />

At APL, o<strong>the</strong>r investigators proposed what may have been <strong>the</strong> first concept for<br />

a hypersonic airplane that merited consideration. In an era when <strong>the</strong> earliest jet<br />

airliners were only beginning to enter service, William Avery leaped beyond <strong>the</strong><br />

supersonic transport to <strong>the</strong> hypersonic transport, at least in his thoughts. His colleague<br />

Eugene Pietrangeli developed a concept for a large aircraft with a wingspan of<br />

102 feet and length of 175 feet, fitted with turbojets and with <strong>the</strong> Dugger-Keirsey<br />

external-burning scramjet, with its short cowl, under each wing. It was to accelerate<br />

to Mach 3.6 using <strong>the</strong> turbojets, <strong>the</strong>n go over to scramjet propulsion and cruise at<br />

Mach 7. Carrying 130 passengers, it was to cross <strong>the</strong> country in half an hour and<br />

achieve a range of 7,000 miles. Its weight of 600,000 pounds was nearly twice that<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Boeing 707 Intercontinental, largest of that family of jetliners. 50<br />

Within <strong>the</strong> Air Force, an important prelude to similar concepts came in 1957<br />

with Study Requirement 89774. It invited builders of large missiles to consider<br />

what modifications might make <strong>the</strong>m reusable. It was not hard to envision that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

might return to a landing on a runway by fitting <strong>the</strong>m with wings and jet engines,<br />

but most such rocket stages were built of aluminum, which raised serious issues of<br />

<strong>the</strong>rmal protection. Still, Convair at least had a useful point of departure. Its Atlas<br />

used stainless steel, which had considerably better heat resistance. 51<br />

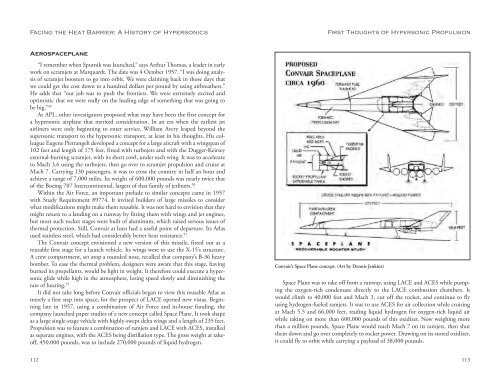

The Convair concept envisioned a new version of this missile, fitted out as a<br />

reusable first stage for a launch vehicle. Its wings were to use <strong>the</strong> X-15’s structure.<br />

A crew compartment, set atop a rounded nose, recalled that company’s B-36 heavy<br />

bomber. To ease <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>rmal problem, designers were aware that this stage, having<br />

burned its propellants, would be light in weight. It <strong>the</strong>refore could execute a hypersonic<br />

glide while high in <strong>the</strong> atmosphere, losing speed slowly and diminishing <strong>the</strong><br />

rate of heating. 52<br />

It did not take long before Convair officials began to view this reusable Atlas as<br />

merely a first step into space, for <strong>the</strong> prospect of LACE opened new vistas. Beginning<br />

late in 1957, using a combination of Air Force and in-house funding, <strong>the</strong><br />

company launched paper studies of a new concept called Space Plane. It took shape<br />

as a large single-stage vehicle with highly-swept delta wings and a length of 235 feet.<br />

Propulsion was to feature a combination of ramjets and LACE with ACES, installed<br />

as separate engines, with <strong>the</strong> ACES being distillation type. The gross weight at takeoff,<br />

450,000 pounds, was to include 270,000 pounds of liquid hydrogen.<br />

112<br />

First Thoughts of Hypersonic Propulsion<br />

Convair’s Space Plane concept. (Art by Dennis Jenkins)<br />

Space Plane was to take off from a runway, using LACE and ACES while pumping<br />

<strong>the</strong> oxygen-rich condensate directly to <strong>the</strong> LACE combustion chambers. It<br />

would climb to 40,000 feet and Mach 3, cut off <strong>the</strong> rocket, and continue to fly<br />

using hydrogen-fueled ramjets. It was to use ACES for air collection while cruising<br />

at Mach 5.5 and 66,000 feet, trading liquid hydrogen for oxygen-rich liquid air<br />

while taking on more than 600,000 pounds of this oxidizer. Now weighing more<br />

than a million pounds, Space Plane would reach Mach 7 on its ramjets, <strong>the</strong>n shut<br />

<strong>the</strong>m down and go over completely to rocket power. Drawing on its stored oxidizer,<br />

it could fly to orbit while carrying a payload of 38,000 pounds.<br />

113