You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

062<br />

Fire will torch the western part of town later this year,<br />

and in 1893, plummeting silver prices will ravage the<br />

economy. By 1900, just 30 years after its founding,<br />

Caribou will be little more than an abandoned speck<br />

on the Colorado map.<br />

Today, slightly more than a century later, the only<br />

whispers of civilization in this alpine meadow are<br />

the crumbling remains of two stone buildings and<br />

a collapsed wooden cabin. Otherwise, it is again a<br />

province of violet and yellow wildflowers that decorate<br />

the hillsides, of hummingbirds that sing over the<br />

landscape and of the chill winds that whistle off the<br />

Continental Divide.<br />

Caribou’s misfortune is a common tale in Colorado<br />

history, evidenced today in the abandoned mines<br />

and buildings that litter the Centennial State. In fact,<br />

only California can claim more ghost towns (due to the<br />

1849 Gold Rush), which are defined by Dr. Tom Noel<br />

of the University of Colorado Denver as places that, at<br />

one point, had a post office and no longer do. Noel, a<br />

bow tie-sporting history professor who answers to the<br />

nickname “Dr. Colorado,” has tallied about 500 such<br />

places in the state. In the counties around Denver, he<br />

says, “There are more ghost towns than live towns.”<br />

Like Caribou, many of Colorado’s ghost towns<br />

trace their roots to the Gold Rush of 1859 or the Silver<br />

Boom that began in the late 1800s. Miners—mostly<br />

young men—would flock after hearing reports of a<br />

new vein, always poised to abandon their new home<br />

if a better opportunity arose, says Thomas Andrews,<br />

assistant professor of history at UC Denver. As a result,<br />

Colorado travelers began seeing ghost towns as early<br />

as the late 1860s.<br />

“It was much easier for a town to develop on hope,”<br />

Andrews says. “Most people hadn’t really come to stay.<br />

They were always looking for the next chance.”<br />

Twenty years prior to Caribou’s boom, that chance<br />

lay 20 miles south of Caribou at Gregory’s Diggings,<br />

later known as Central City. Journalist and future presidential<br />

candidate Horace Greeley traveled by mule to<br />

the area in 1859, five weeks after word spread of a gold<br />

ore discovery there. The journey from Denver, which<br />

today takes about 50 minutes by car, required two arduous<br />

days—illustrating to Greeley the magnitude of the<br />

fever that had seized early miners.<br />

“Six weeks ago, this ravine was solitude,” he wrote<br />

in a dispatch to the New York Tribune. “I presume less<br />

than half the four or five thousand people now in this<br />

ravine have been here a week; he who has been here<br />

three weeks is regarded as quite an old settler.”<br />

Near the southwestern edge of the ravine sprang the<br />

town of Nevadaville, which became home to a business<br />

district with a grocery store, post office, barbershop and<br />

even a lecture hall. Nevadaville soon boasted a population<br />

of several thousand—a bit larger than Denver at<br />

GO MAGAZINE OCTOBER <strong>2009</strong><br />

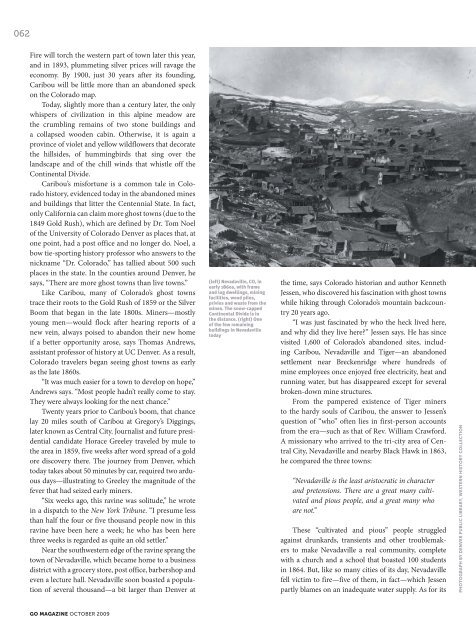

(left) Nevadaville, CO, in<br />

early 1860s, with frame<br />

and log dwellings, mining<br />

facilities, wood piles,<br />

privies and waste from the<br />

mines. The snow-capped<br />

Continental Divide is in<br />

the distance. (right) One<br />

of the few remaining<br />

buildings in Nevadaville<br />

today<br />

the time, says Colorado historian and author Kenneth<br />

Jessen, who discovered his fascination with ghost towns<br />

while hiking through Colorado’s mountain backcountry<br />

20 years ago.<br />

“I was just fascinated by who the heck lived here,<br />

and why did they live here?” Jessen says. He has since<br />

visited 1,600 of Colorado’s abandoned sites, including<br />

Caribou, Nevadaville and Tiger—an abandoned<br />

settlement near Breckenridge where hundreds of<br />

mine employees once enjoyed free electricity, heat and<br />

running water, but has disappeared except for several<br />

broken-down mine structures.<br />

From the pampered existence of Tiger miners<br />

to the hardy souls of Caribou, the answer to Jessen’s<br />

question of “who” often lies in first-person accounts<br />

from the era—such as that of Rev. William Crawford.<br />

A missionary who arrived to the tri-city area of Central<br />

City, Nevadaville and nearby Black Hawk in 1863,<br />

he compared the three towns:<br />

“Nevadaville is the least aristocratic in character<br />

and pretensions. There are a great many cultivated<br />

and pious people, and a great many who<br />

are not.”<br />

These “cultivated and pious” people struggled<br />

against drunkards, transients and other troublemakers<br />

to make Nevadaville a real community, complete<br />

with a church and a school that boasted 100 students<br />

in 1864. But, like so many cities of its day, Nevadaville<br />

fell victim to fire—five of them, in fact—which Jessen<br />

partly blames on an inadequate water supply. As for its<br />

PHOTOGRAPH BY DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY, WESTERN HISTORY COLLECTION