may-2010

may-2010

may-2010

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TRAVEL MEXICO<br />

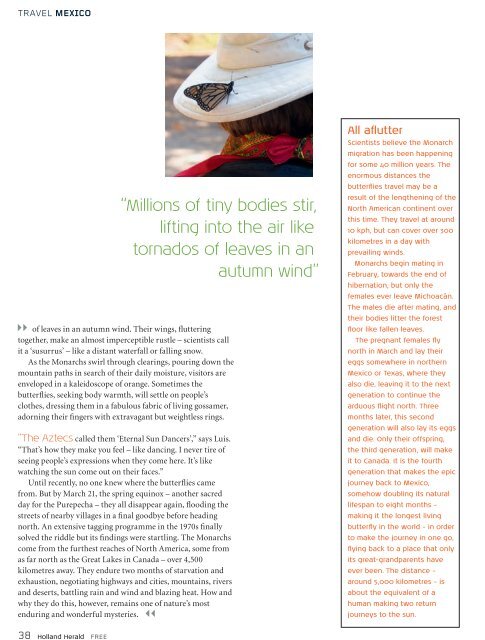

of leaves in an autumn wind. Their wings, fl uttering<br />

together, make an almost imperceptible rustle – scientists call<br />

it a ‘susurrus’ – like a distant waterfall or falling snow.<br />

As the Monarchs swirl through clearings, pouring down the<br />

mountain paths in search of their daily moisture, visitors are<br />

enveloped in a kaleidoscope of orange. Sometimes the<br />

butterfl ies, seeking body warmth, will settle on people’s<br />

clothes, dressing them in a fabulous fabric of living gossamer,<br />

adorning their fi ngers with extravagant but weightless rings.<br />

“The Aztecs called them ‘Eternal Sun Dancers’,” says Luis.<br />

“That’s how they make you feel – like dancing. I never tire of<br />

seeing people’s expressions when they come here. It’s like<br />

watching the sun come out on their faces.”<br />

Until recently, no one knew where the butterfl ies came<br />

from. But by March 21, the spring equinox – another sacred<br />

day for the Purepecha – they all disappear again, fl ooding the<br />

streets of nearby villages in a fi nal goodbye before heading<br />

north. An extensive tagging programme in the 1970s fi nally<br />

solved the riddle but its fi ndings were startling. The Monarchs<br />

come from the furthest reaches of North America, some from<br />

as far north as the Great Lakes in Canada – over 4,500<br />

kilometres away. They endure two months of starvation and<br />

exhaustion, negotiating highways and cities, mountains, rivers<br />

and deserts, battling rain and wind and blazing heat. How and<br />

why they do this, however, remains one of nature’s most<br />

enduring and wonderful mysteries.<br />

38 Holland Herald FREE<br />

“Millions of tiny bodies stir,<br />

lifting into the air like<br />

tornados of leaves in an<br />

autumn wind”<br />

All afl utter<br />

Scientists believe the Monarch<br />

migration has been happening<br />

for some 40 million years. The<br />

enormous distances the<br />

butterfl ies travel <strong>may</strong> be a<br />

result of the lengthening of the<br />

North American continent over<br />

this time. They travel at around<br />

10 kph, but can cover over 300<br />

kilometres in a day with<br />

prevailing winds.<br />

Monarchs begin mating in<br />

February, towards the end of<br />

hibernation, but only the<br />

females ever leave Michoacán.<br />

The males die after mating, and<br />

their bodies litter the forest<br />

fl oor like fallen leaves.<br />

The pregnant females fl y<br />

north in March and lay their<br />

eggs somewhere in northern<br />

Mexico or Texas, where they<br />

also die, leaving it to the next<br />

generation to continue the<br />

arduous fl ight north. Three<br />

months later, this second<br />

generation will also lay its eggs<br />

and die. Only their offspring,<br />

the third generation, will make<br />

it to Canada. It is the fourth<br />

generation that makes the epic<br />

journey back to Mexico,<br />

somehow doubling its natural<br />

lifespan to eight months –<br />

making it the longest living<br />

butterfl y in the world – in order<br />

to make the journey in one go,<br />

fl ying back to a place that only<br />

its great-grandparents have<br />

ever been. The distance –<br />

around 5,000 kilometres – is<br />

about the equivalent of a<br />

human making two return<br />

journeys to the sun.