London Wider Waste Strategy - London - Greater London Authority

London Wider Waste Strategy - London - Greater London Authority

London Wider Waste Strategy - London - Greater London Authority

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Policy & Partnerships<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Wider</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

Background Study<br />

Technical Report to the<br />

<strong>Greater</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Authority</strong><br />

prepared by<br />

Land Use Consultants<br />

and SLR Consulting Ltd<br />

June 2004

Text copyright<br />

<strong>Greater</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Authority</strong><br />

City Hall<br />

The Queen’s Walk<br />

<strong>London</strong> SE1 2AA<br />

June 2004<br />

ISBN<br />

www.london.gov.uk<br />

enquiries 020 7983 4100<br />

minicom 020 7983 4458<br />

2

CONTENTS<br />

1. Introduction 1<br />

2. <strong>Waste</strong> Policy and Legislation 3<br />

3. Sources of advice and assistance 15<br />

4. Commercial and Industrial <strong>Waste</strong> 19<br />

5. Construction and Demolition <strong>Waste</strong> 74<br />

6. Special/Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong> 95<br />

7. Findings and Recommendations 119<br />

Appendix A: <strong>Waste</strong> policy and legislation 143<br />

European Policy 143<br />

European Legislation 144<br />

Horizontal Legislation 144<br />

Treatment Specific Legislation 144<br />

Stream Specific Legislation 145<br />

UK Policy 147<br />

UK Legislation 148<br />

Appendix B: Consultees for Commercial and Industrial <strong>Waste</strong> 154<br />

Appendix C: <strong>London</strong>’s Companies by Size and Sector (Data Based on Small Business<br />

Service Website) 156<br />

Appendix D: Results of Further Analysis of C&I Compositional Data 159<br />

Appendix E: Local <strong>Authority</strong> C&I Collection and Disposal Survey 163<br />

Appendix F: Consultees for Construction and Demolition <strong>Waste</strong> 179<br />

Appendix G: Policy, legislative and other measures influencing the high recycling rates<br />

of C&D waste in Germany, Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands 181<br />

Appendix H: Consultees for Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong>s 186<br />

3

1. Introduction<br />

1.1. Land Use Consultants (LUC) and SLR Consulting Ltd (SLR) were commissioned by the<br />

<strong>Greater</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Authority</strong> (GLA) in March 2004 to undertake a background study on<br />

the management of wider waste to inform the development of a strategy covering all<br />

controlled waste in <strong>London</strong>. The wider waste strategy is intended to be complementary<br />

to, and build upon the principles and policies laid out in The <strong>London</strong> Plan: Spatial<br />

Development <strong>Strategy</strong> for <strong>Greater</strong> <strong>London</strong> (February 2004), and Rethinking Rubbish in<br />

<strong>London</strong>: The Mayor’s Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong> (September 2003). The<br />

term ‘wider waste’ is used in this project to refer to the following controlled waste<br />

streams:<br />

• Commercial and Industrial (C&I) waste, including the commercial component of<br />

municipal waste;<br />

• Construction and Demolition (C&D) waste; and<br />

• Special/Hazardous wastes.<br />

1.2. The objective of the project is to evaluate current management strategies in <strong>London</strong> for<br />

the controlled waste streams listed above, and to provide sufficient evidence and data<br />

to inform the development of appropriate policies within the context of a strategy for all<br />

wastes.<br />

Scope of the Project<br />

1.3. The scope of the project is to:<br />

• Review, and supplement where possible, existing data and information on controlled<br />

waste in <strong>London</strong>, making recommendations for further action where necessary.<br />

• Examine existing management practices for controlled wastes in <strong>London</strong>.<br />

• Undertake a sector based review and consult with key stakeholders.<br />

• Examine effectiveness and applicability of different instruments and measures<br />

utilised to promote more sustainable management of controlled waste.<br />

• Formulate any recommendations for <strong>London</strong> in line with existing and proposed<br />

policy and legislative frameworks.<br />

Approach<br />

1.4. Data collation and analysis on the management of the three streams of wider waste has<br />

been undertaken by reviewing existing information and data, and consulting with waste<br />

management companies operating in <strong>London</strong>, research organisations, local authorities<br />

and national government departments and agencies. An analysis of national and<br />

European legislation and policy applying to wider waste has also been carried out.<br />

Examples of good practice and initiatives within the UK and Europe were sought<br />

through consultation with UK trade associations and organisations promoting<br />

sustainable waste management in <strong>London</strong>, and government agencies in Europe. The<br />

methods used and consultations undertaken are presented in more detail in each<br />

chapter.<br />

Structure of the Technical Report<br />

1.5. This Technical Report sets out the findings of the research and consultations, and<br />

comprises six chapters in addition to this introduction:<br />

1

Chapter 2 summarises the principal legislation and policy applying to controlled<br />

waste and identifies some of its strengths and weaknesses in respect to wider waste.<br />

Chapter 3 provides brief descriptions of the trade associations and organisations<br />

promoting and providing assistance for sustainable waste management in<br />

<strong>London</strong>, whose activities are discussed further in Chapter 4.<br />

Chapter 4 sets out and reviews the collated existing information on the Commercial<br />

and Industrial waste stream in <strong>London</strong>. Chapter 4 also presents the results of<br />

consultations with waste management companies, recyclers, reprocessors, the<br />

Environment Agency, local authorities, the organisations described in Chapter 3 and<br />

water authorities, that were undertaken to build up a profile of the C&I waste<br />

management industry in <strong>London</strong> and identify the potential to influence and promote<br />

waste minimisation, recycling and diversion from landfill.<br />

Chapter 5 presents and reviews the collated existing information on the<br />

Construction and Demolition waste stream in <strong>London</strong>. Chapter 5 also sets out<br />

results of consultations with construction, demolition and waste management and<br />

recycling companies, research organisations and consultants, and the Environment<br />

Agency to address the gaps in the literature review, build up a profile of the C&D waste<br />

management industry and identify the potential applicability of specific measures and<br />

instruments to promote waste minimisation, recycling and diversion from landfill.<br />

Chapter 6 sets out and reviews the collated existing information on the<br />

Special/Hazardous waste stream in <strong>London</strong>. Results of discussions with the<br />

Environment Agency and the Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong> Forum during the collation of existing<br />

information are incorporated in this chapter. Questions regarding special/hazardous<br />

waste management were also posed to the waste management companies during<br />

consultations about commercial and industrial waste and construction and demolition<br />

waste.<br />

Chapter 7 summarises the key findings from Chapters 4-6 and presents an overview<br />

of these findings under cross-cutting themes, followed by a summary of the key<br />

findings for each of the three waste streams. The recommendations generated from<br />

the findings in Chapters 4-6 are also listed in Chapter 7 in consecutive order by waste<br />

stream. The resulting actions to be included as part of the development of the GLA’s<br />

‘<strong>Wider</strong> <strong>Waste</strong>s’ <strong>Strategy</strong> are listed in a table. Each action is prioritised and the relevant<br />

parties responsible for the implementation are identified.<br />

2

2. <strong>Waste</strong> Policy and Legislation<br />

Overview<br />

2.1. This chapter summarises the main legislation and policy applying to controlled waste<br />

and identifies some of its strengths and weaknesses in respect of wider wastes.<br />

Appendix A contains further detail on European Directives and UK legislation and<br />

policy applying to controlled waste, including those referred to in this chapter (marked<br />

with*).<br />

2.2. The purpose of this chapter is to consider the extent to which the current waste<br />

planning framework supports or provides opportunities for sustainable management of<br />

wider wastes. Strategic national policy and current <strong>London</strong> policy are considered first,<br />

to set the scene, followed by a more detailed analysis of current and pending legislation<br />

and initiatives.<br />

Strategic <strong>Waste</strong> Policy<br />

National Policy<br />

2.3. ‘<strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 2000’*is the primary Government policy document on waste<br />

management. ‘<strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 2000’ was followed in 2002 by ‘<strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want<br />

Not’*, a report from the Prime Minister’s <strong>Strategy</strong> Unit which had been asked to carry<br />

out a review of <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 2000. The specific tasks for this review were :<br />

• to analyse the scale of the challenge posed by growing quantities of household<br />

waste;<br />

• to assess the main causes and drivers behind this growth now and in the future; and<br />

• to devise a strategy, with practical and cost-effective measures for addressing the<br />

challenge, which will put England on a sustainable path for managing future streams<br />

of household waste.<br />

2.4. Although the original terms of reference focused on household waste, the report<br />

included substantial commentary and recommendations on wider wastes in recognition<br />

that wider waste volumes are greater than municipal volumes and that the management<br />

of municipal and wider wastes is interlinked.<br />

2.5. In 2003 the Government Response to ‘<strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want Not’ broadly accepted the<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> Unit’s recommendations and set out the Government’s intended actions.<br />

2.6. Key policy proposals in these documents that are relevant to wider wastes are<br />

summarised below.<br />

3

Key policy proposals in ‘<strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 2000’ (relevant to wider wastes)<br />

• By 2005, to reduce the amount of industrial and commercial waste landfilled to 85%<br />

of 1998 levels.<br />

• To use the Landfill Tax escalator as the key tool to reduce landfill of waste.<br />

• To develop new and stronger markets for recycled materials through the <strong>Waste</strong> and<br />

Resources Action Programme (WRAP).<br />

• To promote public procurement of recycled products.<br />

• To introduce producer responsibility initiatives beyond existing packaging initiatives<br />

to include end-of-life vehicles, batteries, and waste electrical and electronic<br />

equipment.<br />

• To affirm the use of Best Practicable Environmental Option (BPEO), the proximity<br />

principle, and the waste hierarchy.<br />

Key policy proposals in ‘<strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want Not’ (relevant to wider wastes and<br />

accepted in principle in the Government’s Response)<br />

• Extend voluntary agreements with industry to reduce waste and increase the use of<br />

recycled materials and the recyclability of products.<br />

• Promote public procurement of recycled products.<br />

• Consider the case for applying incentives such as economic instruments to<br />

encourage environmentally-friendly products.<br />

• Promote the use of secondary resources through BSI standards.<br />

• Finalise central Government targets for the use of recycled materials. All<br />

Departments to also have in place a trained Green Procurement Officer.<br />

• Encourage local authorities to establish environmental procurement policies and set<br />

their own targets.<br />

• Encourage the development of quality standards for compost, ensuring in particular<br />

that the needs of the customer are taken fully into account.<br />

• Increase the Landfill Tax to £35 per tonne for active waste, in the medium term.<br />

• Consider, in 2006/07, the case for banning the landfilling or incineration of<br />

recyclable products.<br />

• Provide guidance to magistrates for prosecution of waste crimes.<br />

• Keep the case for an incineration tax under review, so that the rise in landfill tax<br />

does not promote incineration at the expense of all other options.<br />

• Bring together the literature and evidence on the relative health and environmental<br />

effects of all the different waste management options;<br />

• Promote education and awareness of waste issues via the <strong>Waste</strong> and Resources<br />

Action Programme (WRAP).<br />

• Develop pilots for more innovative waste management practices in partnership with<br />

industry and local authorities.<br />

4

• Set up a delivery taskforce to fill the gap between national policy and local plans.<br />

• Expand the coverage of Envirowise to 20% of UK companies over the next two<br />

years.<br />

• Accelerate the current programme of work to improve delivery of Private Finance<br />

Initiative (PFI) waste projects. 1<br />

• Reform the Landfill Tax Credit Scheme to adopt a more strategic approach to waste,<br />

to tackle priority areas for investment in waste management.<br />

• Redirect landfill tax revenue to incentivise investment in reduction, re-use and<br />

recycling.<br />

• Strengthen waste policy-making, strategic planning, technical, legal and other<br />

services available to DEFRA.<br />

• Allocate addition funding to WRAP.<br />

• Revise PPG10 to ensure all required facilities for recycling residual waste<br />

management can proceed.<br />

• Ensure that Best Value Indicators support waste reduction and recycling.<br />

• Ensure clear definition of all hazardous waste is developed and disseminated<br />

• Assess existing and planned capacity for hazardous waste management and establish<br />

a Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong> Forum.<br />

• Assess the potential for fly-tipping of hazardous waste in light of legislative<br />

requirements.<br />

Further recommendations specific to commercial and industrial waste:<br />

• Explore the potential for supporting the wider development of waste exchanges.<br />

• Consider the value of mandatory environmental reporting.<br />

• Increase the role of waste minimisation clubs.<br />

• Consider the use of statutory targets for commercial and industrial waste. Consider<br />

increasing targets after 2005 (subject to data availability, and with voluntary<br />

arrangements as the preferred option).<br />

2.7. Some of the proposals in ‘<strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want Not’ have already been implemented and<br />

others are due to be implemented through legislation currently being developed. Those<br />

already implemented include a stepped increase in Landfill Tax, reform of the Landfill<br />

Tax Credit Scheme, and development of a Sustainable <strong>Waste</strong> Management Programme<br />

at DEFRA. The recommendation in ‘<strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want Not’, that an independent body<br />

should bring together the evidence on the relative health and environmental effects of<br />

waste management options has been progressed by the recent publication of the<br />

document Review of Environmental and Health Effects of <strong>Waste</strong> Management:<br />

Municipal Solid <strong>Waste</strong> and Similar <strong>Waste</strong>s. 2<br />

1 PFI projects are mainly relevant to municipal waste streams managed by local authorities, although there could be<br />

spillover benefits to wider waste streams.<br />

2 Review of Environmental and Health Effects of <strong>Waste</strong> Management: Municipal Solid <strong>Waste</strong> and Similar <strong>Waste</strong>s.<br />

Enviros and University of Birmingham, for Defra. May 2004.<br />

5

2.8. The national Planning Policy Guidance Note 10* (PPG10) sets out guidance on how the<br />

land-use planning system should contribute to sustainable waste management,<br />

including criteria for siting facilities. The Government is currently reviewing PPG10 in<br />

line with the delivery of the reforms to the planning system, and a consultation draft of<br />

the revised Planning Policy Statement 10 (PPS10) is due out later this year.<br />

2.9. New legislation and regulations developed since ‘<strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want Not’ are:<br />

• End of life vehicles regulations (2003).<br />

• <strong>Waste</strong> electrical and electronic equipment regulations (under development).<br />

• The <strong>Waste</strong> Emissions and Trading Act (2003).<br />

• Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong> Regulations (to come into force this year).<br />

<strong>London</strong> Policy<br />

Vision for <strong>London</strong><br />

2.10. The Mayor’s vision is “to develop <strong>London</strong> as an exemplary, sustainable world city, based<br />

on three interwoven themes:<br />

• strong, diverse long term economic growth;<br />

• social inclusiveness to give all <strong>London</strong>ers the opportunity to share in <strong>London</strong>’s<br />

future success;<br />

• fundamental improvements in <strong>London</strong>’s environment and use of resources.”<br />

Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

2.11. Chapter 3 of the Mayor’s Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong> 3 interprets this vision<br />

in relation to municipal waste as:<br />

The Year 2020 Vision for <strong>Waste</strong> in <strong>London</strong><br />

The Mayor’s Vision for <strong>Waste</strong> in 2020 in <strong>London</strong> is that <strong>London</strong>’s municipal waste no<br />

longer compromises a wider vision for <strong>London</strong> as a sustainable city. To achieve this,<br />

wasteful lifestyle habits must change so that we all produce only the absolute minimum<br />

amounts of waste, and the environment is no longer under pressure from waste. We<br />

need to ensure that municipal waste is managed in a way that minimises the adverse<br />

impact on the local and global environment, and on <strong>London</strong> communities, economy and<br />

health.<br />

2.12. The Mayor also recognises the need for a wider <strong>Strategy</strong> to provide a framework for the<br />

planning of all waste management in <strong>London</strong>. The Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> defines a series of objectives that are consistent with national policy and<br />

legislation. These objectives could apply equally to wider waste and are considered to be<br />

a starting point for wider waste policies, as noted in the specification for this project.<br />

Objectives of the Mayor’s Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

It is the Mayor’s objective to develop a ‘waste reduction, reuse and recycling-led’,<br />

cohesive and sustainable strategy for the management of <strong>London</strong>’s waste which will:<br />

3 Rethinking Rubbish in <strong>London</strong> The Mayor’s Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong>. <strong>Greater</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Authority</strong>.<br />

September 2003.<br />

6

• Change the way we use resources so that we waste less. This will require us to deal<br />

with waste in a sustainable way, and people and communities to take responsibility<br />

for their waste.<br />

• Reduce the amount of (municipal) waste produced in <strong>London</strong>.<br />

• Increase the proportion of <strong>London</strong>’s (municipal) waste being reused.<br />

• Increase the proportion of <strong>London</strong>’s (municipal) waste being recycled and ensure<br />

recycling facilities are available for all.<br />

• Ensure that waste is managed in such a way as to minimise the impact on the<br />

environment and health.<br />

• Move <strong>London</strong> towards becoming more self-sufficient in managing its (municipal)<br />

waste within the region, and towards waste being dealt with as close to the place of<br />

production as possible. 4<br />

• Meet the objectives of the National <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> and Landfill Directive, and other<br />

European Directives, by reducing the amount of <strong>London</strong>’s biodegradable municipal<br />

waste sent to landfill and reducing the toxicity of waste.<br />

• Increase capacity of, stabilise and diversify the markets for recyclables in <strong>London</strong>;<br />

including green purchasing and encouraging redesign of goods and services to<br />

increase consumer choice.<br />

• Maximise opportunities to optimise economic development and job creation<br />

opportunities in the waste management and reprocessing sectors, contribute to the<br />

improvement of the local community, and directly or indirectly improve the health of<br />

<strong>London</strong>ers.<br />

• Strategically plan waste facilities for <strong>London</strong> that meet the needs of the <strong>Waste</strong><br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> and enable its implementation.<br />

• Collect and share data and information on municipal waste management in <strong>London</strong>,<br />

and other places; the identification and dissemination of best practice will help to<br />

improve performance and reduce inefficiencies.<br />

• Minimise the transport of waste by road and maximise the opportunities for the<br />

sustainable use of rail and water.<br />

• Improve the local environment and street scene environment.<br />

The <strong>London</strong> Plan<br />

2.13. The <strong>London</strong> Plan also has a key role in relation to the spatial elements of sustainable<br />

waste management. Cross-cutting policies in the <strong>London</strong> Plan (see boxes below)<br />

emphasise the proximity principle, set overall recycling targets, and indicate (inter alia)<br />

that boroughs should:<br />

• safeguard existing waste management sites;<br />

• identify new sites, and support proposals, for activities such as recycling,<br />

composting, manufacturing based on recycled materials, and recovery from residual<br />

waste;<br />

• ensure that the provisions of BPEO are applied;<br />

4 These targets are quantified in the <strong>London</strong> Plan (see next section), rising from 75% self-sufficiency in 2010 to<br />

85% in 2020.<br />

7

• where waste cannot be dealt with locally, promote waste facilities that have good<br />

access to river or rail transhipments;<br />

• forecast waste arisings by stream and forecast imports and exports of waste.<br />

Policy 4A.1 <strong>Waste</strong> strategic policy and targets<br />

In order to meet the national policy aim that most waste should be treated or disposed<br />

of within the region in which it is produced (regional self-sufficiency) the Mayor will<br />

work in partnership with the <strong>London</strong> boroughs, the Environment Agency, statutory<br />

waste disposal authorities and operators to ensure that facilities with sufficient capacity<br />

to manage 75 per cent (16 million tonnes) of waste arising within <strong>London</strong> are provided<br />

by 2010, rising to 80 per cent (19 million tonnes) by 2015 and 85 per cent (22.5 million<br />

tonnes) by 2020. An early alteration to this plan will seek to bring forward regional self<br />

sufficiency targets for individual waste streams.<br />

The Mayor will work in partnership with the Government, boroughs, Environment<br />

Agency, statutory waste disposal authorities and operators to minimise the level of<br />

waste generated, increase re-use and recycling and composting of waste and reduce<br />

landfill disposal. Boroughs should ensure that land resources are available to implement<br />

the Mayor’s Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong>, <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 2000, the Landfill<br />

Directive and other EU directives on waste.<br />

The Mayor will work in partnership with the waste authorities, Environment Agency and<br />

operators to exceed recycling or composting levels in household waste of:<br />

25 per cent by 2005<br />

30 per cent by 2010<br />

33 per cent by 2015.<br />

The minimum quantities represented by those targets are 1 million tonnes in 2005, 1.35<br />

million tonnes in 2010 and 1.65 million tonnes in 2015. This would leave some 3.05<br />

million tonnes in 2005, 3.1 million tonnes in 2010 and 3.25 million tonnes in 2015 to be<br />

dealt with by other means, with a declining reliance on landfill and an increasing use of<br />

new and emerging technologies.<br />

Having regard to the existing incineration capacity in <strong>London</strong> and with a view to<br />

encouraging an increase in waste minimisation, recycling, composting and the<br />

development of new and emerging advanced conversion technologies for waste, the<br />

Mayor will consider these waste management methods in preference to any increase in<br />

mass-burn incineration capacity. Each case, however, will be treated on its individual<br />

merits. The aim is that current incinerator capacity will, over the lifetime of this plan,<br />

become orientated towards non-recyclable residual waste.<br />

Policy 4A.2 Spatial policies for waste management<br />

In support of the Mayor’s Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong>, the proximity<br />

principle and the need to plan for all waste streams, UDP policies should:<br />

• safeguard all existing waste management sites (unless appropriate compensatory<br />

provision is made);<br />

8

• identify new sites in suitable locations for new facilities, such as Civic Amenity sites,<br />

construction and demolition waste recycling plants and closed vessel composting;<br />

• require the provision of suitable waste and recycling storage facilities in all new<br />

developments;<br />

• ensure that the principles of Best Practical Environmental Option are applied;<br />

• support appropriate developments for manufacturing related to recycled waste<br />

• support treatment facilities to recover value from residual waste<br />

• where waste cannot be dealt with locally, promote waste facilities that have good<br />

access to river or rail transport<br />

• identify and forecast for the period covered by the UDP total waste arisings, that is<br />

controlled wastes that include municipal waste and also commercial, industrial,<br />

hazardous and inert arisings, and the amount of waste that will be imported or<br />

exported.<br />

The Mayor will promote the co-ordination of the boroughs’ waste policies by bringing<br />

forward, as an early alteration to this plan, strategic guidance which will evaluate the<br />

adequacy of existing strategically important waste management and disposal facilities to<br />

meet <strong>London</strong>’s future needs, both for municipal and other waste streams, and identify<br />

the number and type of new or enhanced facilities required to meet those needs and<br />

the opportunities for the broad location of such facilities. This guidance will provide<br />

sufficient sub-regional guidance, including the disposal of waste arisings from the<br />

central sub-region, to inform the preparation of SRDFs and UDPs. Until the alteration of<br />

this plan is brought forward, the Mayor will work with boroughs to identify strategically<br />

important sites and will expect boroughs to apply the provisions set out in this Policy<br />

and Policies 4A.1 and 4A.3 in bringing forward development plans and in considering<br />

development proposals. He will also work with the South East England and East of<br />

England regional authorities to co-ordinate strategic waste management across the<br />

three regions.<br />

Policy 4A.3 Criteria for the selection of sites for waste management and<br />

disposal<br />

UDP policies should incorporate the following criteria to identify sites and allocate<br />

sufficient land for waste management and disposal:<br />

• proximity to source of waste;<br />

• the nature of activity proposed and its scale;<br />

• the environmental impact on surrounding areas, particularly noise, emissions, odour<br />

and visual impact;<br />

• the transport impact, particularly the use of rail and water transport<br />

• primarily using sites that are located on Preferred Industrial Locations or existing<br />

waste management locations.<br />

The Mayor will keep these criteria under review, and SRDFs should reflect the need for<br />

any sub-regional interpretation.<br />

9

Policies of neighbouring regions<br />

2.14. The Regional <strong>Waste</strong> Management Strategies of neighbouring regions are of significance<br />

for <strong>London</strong>’s waste management as significant waste transfers occur between regions.<br />

Although waste travels in both directions, the overall effect is a net export of waste<br />

from <strong>London</strong>, particularly to the South East England and East of England regions.<br />

2.15. The South East England Regional Assembly published ’No Time To <strong>Waste</strong>: Proposed<br />

Alterations to RPG South East – Regional <strong>Waste</strong> Management <strong>Strategy</strong>’ in March 2004.<br />

The equivalent document for the East of England is the ’East of England Regional <strong>Waste</strong><br />

Management <strong>Strategy</strong>’ (2002). Both strategies contain policies to reduce the disposal<br />

of <strong>London</strong>’s waste at sites in their regions.<br />

2.16. The East of England Regional Assembly proposes in Policy 3 to only accept the import<br />

of waste from outside the Region in very special circumstances after 2010. Only<br />

residues from waste processing in <strong>London</strong> will be acceptable in landfills in the East of<br />

England region, and new non-landfill waste facilities dealing primarily with waste from<br />

outside the Region will not be permitted unless there is a clear benefit to the Region.<br />

The implementability of this policy and the achievement of regional self-sufficiency<br />

within the East of England, South East and <strong>London</strong> regions, is currently being<br />

considered in another study 5 looking at inter-regional waste movements.<br />

2.17. The South East of England makes provision for a declining amount of <strong>London</strong>’s waste to<br />

landfill and, after 2016, Policy W3 states that waste authorities and waste management<br />

companies “will only provide for residual waste that has been subject to recovery<br />

processes or from which value cannot be recovered. Provision for recovery and<br />

processing capacity for <strong>London</strong>’s waste should only be made where there is a proven<br />

need, with demonstrable benefits to the region…A net balance in movement of<br />

materials for recovery and reprocessing between the region and <strong>London</strong> should be in<br />

place by 2016.”<br />

European Legislation and Policy Initiatives<br />

2.18. European waste legislation can be considered in three categories:<br />

• Horizontal legislation that establishes the overall framework, including definitions<br />

and general principles.<br />

• Treatment-specific legislation relating to particular waste treatment options, such as<br />

incineration.<br />

• <strong>Waste</strong> stream-specific legislation relating to individual streams such as WEEE, ELVs<br />

and batteries.<br />

2.19. The overarching framework is provided by the <strong>Waste</strong> Framework Directive* (WFD)<br />

(1975, revised in 1991 and 1996) which sets out the policy principles for waste<br />

management by Member States. The WFD requires Member States to give priority to<br />

waste prevention and to encourage re-use and recovery of waste, to protect the<br />

environment and human health, to develop waste management plans and to establish a<br />

system for the authorisation of waste management installations. The Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong><br />

Directive (HWD) (1991) provides further specific requirements to complement the WFD<br />

in relation to hazardous waste, including requirements for permitting of installations<br />

handling hazardous waste, controls on transport and record-keeping and tracking<br />

5 Assessment of Regional <strong>Waste</strong> Movements is due to be published at the end of August 2004 by M.E.L Research<br />

Ltd.<br />

10

equirements. The various treatment-specific and waste stream-specific Directives build<br />

on the basic framework of the WFD and HWD.<br />

2.20. In July 2002 the European Parliament published ‘Environment 2010: Our Future, Our<br />

Choice – The Sixth Environment Action Programme of the European Community’*<br />

(EAP). This identifies four priority areas for action, one of which is ‘sustainable use of<br />

natural resources and management of wastes’. <strong>Waste</strong> management also has strong<br />

linkages to other priority areas of tackling climate change, environment and health and<br />

(perhaps less directly) nature and biodiversity. The EAP includes objectives, targets and<br />

actions which are reproduced below. The objectives and targets are, in general, more<br />

ambitious than current UK policy.<br />

Objectives<br />

• To decouple the generation of waste from economic growth and achieve a<br />

significant overall reduction in the volumes of waste generated through improved<br />

waste prevention initiatives, better resource efficiency, and a shift to more<br />

sustainable consumption patterns.<br />

For wastes that are still generated, to achieve a situation where:<br />

• the wastes are non-hazardous or at least present only very low risks to the<br />

environment and our health;<br />

• the majority of the wastes are either reintroduced into the economic cycle,<br />

especially by recycling, or are returned to the environment in a useful (e.g.<br />

composting) or harmless form;<br />

• the quantities of waste that still need to go to final disposal are reduced to an<br />

absolute minimum and are safely destroyed or disposed of;<br />

• waste is treated as closely as possible to where it is generated.<br />

Targets<br />

Within a general strategy of waste prevention and increased recycling, to achieve in the<br />

lifetime of the programme a significant reduction in the quantity of waste going to final<br />

disposal and in the volumes of hazardous waste generated:<br />

• reduce the quantity of waste going to final disposal by around 20% by 2010<br />

compared to 2000, and in the order of 50% by 2050;<br />

• reduce the volumes of hazardous waste generated by around 20% by 2010<br />

compared to 2000 and in the order of 50% by 2020.<br />

Proposed actions with relevance to waste in the EU 6 th<br />

Environmental Action Programme<br />

• Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> on the sustainable use of resources.<br />

• Integrate waste prevention objectives and criteria into the Community’s Integrated<br />

Product Policy and the Community <strong>Strategy</strong> on Chemicals.<br />

• Revised Directive on sludges.<br />

• Recommendation on construction and demolition wastes.<br />

• Legislative initiative on biodegradable wastes.<br />

11

• A Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> on waste recycling to include the following types of actions:<br />

Identify which wastes should be recycled as a priority, based on criteria which are linked<br />

to the resource management priorities and to the results of analyses that identify where<br />

recycling produces an obvious net environmental benefit, and to the ease and cost of<br />

recycling the wastes.<br />

Formulate policies and measures that ensure that the collection and recycling of these<br />

priority waste streams occurs, including indicative recycling targets and monitoring<br />

systems to track and compare progress by Member States.<br />

Identify policies and instruments to encourage the creation of markets for recycled<br />

materials.<br />

2.21. In response to the last of these proposals, in May 2003 the European Commission<br />

adopted an interim Communication entitled ‘Towards a Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> on the<br />

Prevention and Recycling of <strong>Waste</strong>’. The objective was ‘to launch a process of<br />

consultation of the Community institutions and of waste management stakeholders to<br />

contribute to the development of a comprehensive and consistent policy on waste<br />

prevention and recycling.’ Section 5 of the Communication introduced a framework for<br />

the future thematic strategy and highlighted the main issues for discussion, on which<br />

stakeholder comments were invited.<br />

2.22. Broadly, the Communication proposed that the future Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> should be<br />

structured around four ‘building blocks’:<br />

• Block 1. Core instruments to promote waste prevention.<br />

• Block 2. Core instruments to promote waste recycling.<br />

• Block 3. Measures to close the waste recycling standards gap.<br />

• Block 4. Accompanying measures to promote waste prevention and recycling.<br />

2.23. <strong>Waste</strong> prevention instruments referred to in the Communication include economic<br />

instruments such as pricing, information campaigns, the ‘Registration, Evaluation and<br />

Authorisation of Chemicals (REACH)’ initiative, waste management plans at the level of<br />

sectors or individual enterprises (e.g. through the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme,<br />

EMAS), although the Communication notes that in general there are not many practical<br />

examples of instruments which could lead to significant quantitative reductions of waste<br />

generation and in which the Community could play a role. The communication also<br />

notes the potential for qualitative prevention of waste, such as replacing hazardous<br />

materials in manufacturing with less hazardous materials, possibly implemented through<br />

the IPPC permitting system.<br />

2.24. <strong>Waste</strong> recycling instruments referred to include landfill taxes (noting the need for<br />

complementary measures to prevent all waste being diverted to incineration), improved<br />

producer responsibility, tradable certificates (noting the UK’s implementation of these<br />

for packaging waste and biodegradable MSW), incentive systems, and prescriptive<br />

instruments such as landfill bans for certain wastes.<br />

2.25. <strong>Waste</strong> recycling standard instruments are measures to ensure a level playing field<br />

between recycling and other waste operations. Instruments referred to include<br />

extension of the IPPC Directive to the whole waste sector, determination of quality<br />

standards for recycling, and the possibility of setting EU-wide emission limits for some<br />

processes.<br />

12

2.26. Accompanying measures referred to include improving the legal framework (such as the<br />

definitions of the terms ‘waste’, ‘recovery’ and ‘disposal’), promoting research and<br />

development and technology demonstration and development, and measures to<br />

promote demand for recycled materials.<br />

2.27. Following the consultation on the Towards a Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> document a series of<br />

stakeholder meetings has been held. The first of these was in February 2004 and<br />

further meetings were held in April 2004. A date for publication of a revised<br />

Communication on the Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> was expected by the end of this year, but has<br />

been pushed back to Spring 2005.<br />

2.28. The direct impacts on the UK waste management situation of a Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> on<br />

Prevention and Recycling of <strong>Waste</strong> are difficult to anticipate. Some of the proposals in<br />

the Communication are regulatory and if carried through would need to be transposed<br />

into UK law. Others relate to promoting or facilitating action, especially those proposals<br />

relating to waste reduction rather than recycling, and these may well have little<br />

immediate impact although they would reinforce aspects of current UK policy contained<br />

in ‘<strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 2000’ and ‘<strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want Not’.<br />

2.29. Other proposed actions in the 6 th EAP relating to waste, such as the proposal for a<br />

recommendation on construction and demolition wastes, have yet to develop into<br />

concrete proposals and will need to be monitored and reacted to as they proceed.<br />

2.30. The proposed ‘Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> on Sustainable Use of Natural Resources’ is also<br />

potentially of fundamental importance to waste management as its overall objective is<br />

to decouple economic growth from resource use and pollution. In October 2003 the<br />

Commission adopted a Communication entitled ‘Towards a Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> on the<br />

Sustainable Use of Natural Resources’, but at present there are few concrete proposals<br />

and the work programme has so far focused on theoretical issues in this very complex<br />

topic.<br />

2.31. In summary, current and emerging EU policy on waste and natural resources indicates<br />

the intention to pursue ambitious targets. While a range of policy instruments are being<br />

considered to bridge the gap between intention and reality it is too early to identify the<br />

preferred choice of instruments, the flexibility that will remain to Member States in<br />

choosing among them, and timeframes for implementation. The publication of the<br />

‘Thematic <strong>Strategy</strong> on the Prevention and Recycling of <strong>Waste</strong>’ consultation draft should<br />

provide greater clarity on some aspects of policy.<br />

<strong>Waste</strong> Streams<br />

2.32. The remainder of this chapter briefly assesses the status of waste legislation, policy and<br />

economic instruments in relation to the main ‘wider wastes’ streams: i.e. commercial and<br />

industrial, construction and demolition, and hazardous wastes.<br />

Commercial and Industrial <strong>Waste</strong><br />

2.33. As noted in the brief for this study, management of commercial and industrial waste<br />

(C&I) is largely market driven. Larger businesses are sensitive to the costs of waste<br />

generation and disposal and are often open to alternative approaches, either on purely<br />

economic grounds or as part of a broader Environmental Management System approach.<br />

By contrast smaller operators generally treat waste management as an unavoidable cost<br />

of doing business and have little time and resources to invest in alternative approaches.<br />

Where waste disposal is delivered as part of a fully serviced facilities contract as for<br />

many offices in <strong>London</strong>, there is even less direct economic incentive for action.<br />

13

2.34. Legislation applying to specific types of C&I waste includes the following:<br />

• Packaging waste, through the Producer Responsibility (Packaging <strong>Waste</strong>)<br />

Regulations 1997*, is the most regulated waste type within the C&I waste stream.<br />

However the Regulations have little direct impact on smaller companies below the<br />

turnover and volume thresholds, being £2m and 50 tonnes of packaging per annum.<br />

• The Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong> Regulations* to be introduced in mid-2004 will require some<br />

wastes, such as monitor screens, to be diverted from the general C&I stream into the<br />

hazardous waste stream.<br />

• The new Batteries Directive which is to replace the Batteries and Accumulators<br />

Directive* later in 2004, is expected to set a collection target of 95% of industrial<br />

batteries and to require 55% of collected battery materials to be recycled, and will<br />

have to be transposed into UK law.<br />

• The End of Life Vehicles Regulations 2003* will require producers to take back or<br />

provide for disposal of vehicles at the end of their useful lives.<br />

2.35. The Landfill Tax Regulations 1996* provide a cost incentive which works to discourage<br />

landfilling of C&I waste to an extent, particularly waste which is defined as ‘active waste’<br />

and is subject to a higher charge.<br />

2.36. The Landfill Regulations 2002* require that certain waste types are not disposed of in<br />

landfills, such as hazardous waste (unless in a hazardous waste landfill), liquid wastes,<br />

whole tyres (from 2003), and shredded tyres (from 2006). While applying in the first<br />

instance to the disposal contractor, the Regulations have an upstream effect on waste<br />

generators who must segregate such wastes for appropriate treatment or disposal.<br />

Construction and Demolition <strong>Waste</strong><br />

2.37. Construction and demolition (C&D) waste management is also largely market driven.<br />

The main legislative requirements relate to contaminated soil from brownfield sites,<br />

which is generally classified as hazardous waste, and asbestos waste. The Producer<br />

Responsibility Regulations 2002* also apply to packaging generated at construction<br />

sites.<br />

2.38. The Aggregates Levy* (implemented under the Finance Act 2001) affects the<br />

management of C&D waste by increasing the cost of virgin aggregates (currently by an<br />

increase of £1.60 per tonne) and thus provides some incentive for re-use and recycling<br />

existing aggregate materials. The Landfill Tax also provides an incentive through the<br />

cost of disposal of waste in landfills (£10/tonne for ‘active’ waste, and £2/tonne for<br />

‘inactive’ (inert) waste). The relatively high transport and disposal costs for C&D waste,<br />

due to the large quantities generated, provide a further financial incentive for re-use<br />

and recycling.<br />

Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong><br />

2.39. The hazardous waste chapter of this report describes the specific legislation applying to<br />

such waste, which is much more extensive than that applying to C&I or C&D waste. The<br />

existing Special <strong>Waste</strong> Regulations 1996* are to be replaced by the Hazardous <strong>Waste</strong><br />

Regulations* in mid-2004, which will increase the volume of waste requiring<br />

management as hazardous waste with a commensurate reduction in the general C&I<br />

waste stream. At the same time, the Landfill Regulations 2002* will prevent co-disposal<br />

of hazardous and non-hazardous wastes from July 2004 and thus limit the disposal<br />

options available.<br />

14

3. Sources of advice and assistance<br />

3.1. The array of bodies operating in <strong>London</strong>, with roles in promoting sustainable waste<br />

management, is somewhat confusing to the outside observer and probably also<br />

confusing to the businesses they are aiming to assist. These bodies include national<br />

organisations, and organisations operating only in <strong>London</strong>.<br />

3.2. The bodies described below provide facilitation, financial assistance, or other assistance<br />

such as advice to promote sustainable waste management. To date, the greatest levels<br />

of assistance have been provided where the waste materials concerned are from<br />

municipal waste collections or where an operation is seen as a pilot or flagship for the<br />

waste recycling and reprocessing industry. In other cases, such as recycling of metals<br />

and paper from commercial and industrial sources and most recycling of construction<br />

and demolition waste, there is little direct assistance to the businesses involved but a<br />

range of other facilitation services may be available. There is also an emerging trend to<br />

provide greater support for SMEs involved in recycling and reprocessing, in addition to<br />

the larger operations which are typically associated with major waste sector businesses.<br />

National bodies and initiatives<br />

3.3. The following bodies operate nationally.<br />

3.4. The <strong>Waste</strong> and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) was established in 2001 to<br />

promote sustainable waste management, in response to <strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 2000. WRAP<br />

gained additional responsibilities following the <strong>Strategy</strong> Unit review of <strong>Waste</strong> Not, Want<br />

Not. Funded by DEFRA, the DTI and the devolved administrations of Scotland, Wales<br />

and Northern Ireland, WRAP’s mission is “to accelerate resource efficiency by creating<br />

stable and efficient markets for recycled materials and products [and] removing barriers<br />

to waste minimisation, re-use and recycling”.<br />

3.5. WRAP’s Revised Business Plan (2004 – 2006) sets out the following work programmes: 6<br />

• market development for six material streams (aggregates, glass, organics, paper,<br />

plastics, and wood), with targets for increasing the national processing capacity for<br />

each stream;<br />

• business development in the recycling sector (a target of £10 million additional<br />

investment per year) and provision of advice to businesses;<br />

• promoting the procurement of recycled materials and products by local authorities<br />

and target business sectors;<br />

• regional market development for recycled materials;<br />

• improvement of local authority recycling collections through training and advice;<br />

• communication and awareness raising aimed at the public;<br />

• promoting waste minimisation in households (through composting and reusable<br />

nappies) and waste minimisation in the retail sector.<br />

3.6. Envirowise is a government-funded programme offering free, independent advice on<br />

environmental issues. It is operated by AEA Technology in Partnership with TTI on<br />

contract to the Department of Trade and Industry with contribution from DEFRA. It was<br />

started in the early 1990s and has saved businesses over £797 million 7 . At present it<br />

6 This is a summary of the text in the Business Plan.<br />

7 Source: Envirowise web-site www.envirowise.gov.uk<br />

15

addresses eight main environmental issues 8 , and has targeted 13 9 industrial and one<br />

commercial (retail) sector.<br />

3.7. <strong>Waste</strong> Watch is an independent not-for-profit organisation funded by central<br />

government, charitable trusts, the corporate sector, individuals, local authorities, and<br />

the national lottery. It works in partnership with a range of public and private<br />

organisations and NGOs and is active in research, policy development and public<br />

education as well as working with business. <strong>Waste</strong>busters is its environmental<br />

consultancy service for businesses, and <strong>Waste</strong> Watch Business Network (WWBN) is a<br />

not-for-profit membership organisation working to help businesses and organisations<br />

save money and increase efficiency through waste reduction. WWBN currently operates<br />

in the <strong>London</strong> boroughs of Camden, Haringey, Islington, Barnet, Harrow, Hillingdon and<br />

within 5 miles of Heathrow Airport. It also operates the ResourceXchange waste<br />

materials exchange service.<br />

3.8. The Environment Agency promotes waste minimisation and recycling to businesses as<br />

part of IPPC permitting and hazardous waste regulation, in addition to its role in<br />

processing licences for waste facilities. The Agency also provides more general<br />

environmental advice to businesses, notably through its online NetRegs information<br />

resource.<br />

3.9. Business Link has a <strong>London</strong> office (Business Link for <strong>London</strong>) that provides a range of<br />

advisory services to businesses. Environmental advice, including waste management<br />

and minimisation, is part of the advice package offered. Business Link also operates<br />

Envirolink, a specialist environmental advisory service owned by the local Business<br />

Links in Bedfordshire and Luton, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Norfolk and<br />

Suffolk. There are currently no plans to extend it to <strong>London</strong>, although its website<br />

provides generally available advice such as best practice guidance.<br />

3.10. The Environmental Services Association (ESA) represents the UK’s waste<br />

management sector. ESA works with government, Parliament and regulators to bring<br />

about a sustainable waste management system for the UK. ESA produces a wide variety<br />

of waste-related information, both for its members and for the public. As well as<br />

specialised reports, ESA produces briefings and policy statements on issues which affect<br />

the waste management industry.<br />

3.11. The Chartered Institution of <strong>Waste</strong>s Management (CIWM) is the professional body<br />

for the waste management industry, which represents over 6,000 members mostly in the<br />

UK, but also overseas. The CIWM sets the professional standards for individuals<br />

working in the waste management industry and has various grades of membership<br />

determined by education, qualification and experience. The CIWM provides conference,<br />

exhibition, training and technical publication services to the waste management<br />

industry. It also works towards advancing the scientific and technical aspects of waste<br />

management for safeguarding the environment.<br />

<strong>London</strong> bodies and initiatives<br />

3.12. The following bodies’ activities are specific to <strong>London</strong>.<br />

8 Cleaner design, cleaner technology, environmental management systems, legislation, packaging, solvents and<br />

VOCs, waste minimisation, and water and effluent.<br />

9 Ceramics, chemical, electronics, engineering, food and drink, foundries, furniture, glass, metal finishing, paper<br />

and board, plastics and rubber, printing and textiles.<br />

16

3.13. <strong>London</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> Action (LWA) was formed in 1997 by the Association of Local<br />

Government and <strong>London</strong> First, to raise the profile of sustainable waste management and<br />

improve waste minimisation and recycling in <strong>London</strong>. A company with a board including<br />

public sector, private sector and NGO representatives, one of LWA’s main roles is<br />

allocating the <strong>London</strong> Recycling Fund. The fund is mainly applied to assist waste<br />

authorities meet their statutory recycling targets. LWA also facilitated dialogue between<br />

businesses, the public and local authorities in the lead-up to the Mayor’s Municipal<br />

<strong>Waste</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong>.<br />

3.14. <strong>London</strong> Remade was formed in 2000 to build on the success of LWA in improving<br />

recycling collection rates by stimulating use of the resulting materials. Like LWA it is<br />

constituted as a company with a public and private sector board. <strong>London</strong> Remade<br />

facilitates the reprocessing of recyclables into materials of an acceptable and consistent<br />

quality and facilitates the use of these materials (and products made from them) by<br />

<strong>London</strong> businesses and public sector organisations. <strong>London</strong> Remade’s objectives and<br />

activities align strongly with WRAP’s national programmes.<br />

3.15. <strong>London</strong> Remade also administers the Mayor’s Green Procurement Code, which now has<br />

320 members including small and large businesses, NGOs, <strong>London</strong> Boroughs, other<br />

public sector organisations such as schools. The Code requires businesses and public<br />

sector organisations to sign up to a staged set of commitments to procuring recycled<br />

materials and products, in a drive to stimulate local markets for <strong>London</strong>’s waste<br />

materials.<br />

3.16. The <strong>London</strong> Development Agency (LDA) has a key role in promoting sustainable<br />

economic development in <strong>London</strong> and through its SRB programme has provided £5.4<br />

million funding to <strong>London</strong> Remade from 2000-2004. The LDA draft economic<br />

development strategy Sustaining Success: Developing <strong>London</strong>’s Economy, is a revision<br />

to the existing economic strategy and aims to integrate economic, social and<br />

environmental objectives. Consultation on the draft economic development strategy<br />

closed in April 2004,. The draft strategy’s first goal, investment in infrastructure and<br />

places, includes specific actions to:<br />

• (4d) Take action to encourage developers and all businesses to adopt<br />

environmentally friendly goods and services.<br />

• (4e) Support the adoption of sustainable construction and design and address the<br />

strategic location needs of waste, recycling and other environmental industries.<br />

3.17. The LDA also commissioned the report Green Alchemy, Turning Green to Gold: Creating<br />

Resource from <strong>London</strong>’s <strong>Waste</strong> (November 2003) as part of its sustainable development<br />

function. This examined possible ways that interventions in resource efficiency and<br />

recycling could help to achieve the LDA’s wider policy goals such as wealth and<br />

employment creation, social progress and environmental improvements. The report<br />

identified market development opportunities for paper, organics, glass, WEEE, wood,<br />

tyres and ELVs. It concluded that WEEE and ELV reprocessing should be given the<br />

highest priority in <strong>London</strong>, based on factors such as the strength of regulatory drivers,<br />

job creation potential, amenity effects and the amounts of land required.<br />

3.18. <strong>London</strong> First is a business membership organisation supported by over 300 of the<br />

capital’s major businesses and public organisations. It acts as a voice for <strong>London</strong><br />

business in the sustainability debate and has commissioned research on <strong>London</strong>’s<br />

ecological footprint and a Triple Bottom Line for <strong>London</strong>. It is also a founding partner<br />

of <strong>London</strong> <strong>Waste</strong> Action.<br />

17

3.19. The <strong>London</strong> Regional Technical Advisory Body (RTAB) is a group of representatives<br />

of <strong>London</strong> waste planning authorities, the waste management industry and the<br />

Environment Agency convened by the GLA. The Government advised all Regional<br />

Planning Bodies (of which the GLA is one) to convene officer-level RTABs to help in the<br />

formulation of Regional Planning Guidance. The <strong>London</strong> RTAB prepares information<br />

and advice on the provision of waste management to inform waste planning policy in<br />

<strong>London</strong>.<br />

3.20. The <strong>London</strong> Sustainability Exchange was established to bring people together from<br />

different sectors to approach the challenges of making <strong>London</strong> sustainable. It identifies<br />

opportunities for strategic partnerships and promotes sharing of knowledge and ideas.<br />

Its current projects include a Sustainable Construction Project and research on<br />

motivational factors for environmental action, although this research has not yet<br />

specifically extended to waste issues.<br />

3.21. The <strong>London</strong> Community Recycling Network (LCRN) is a not for profit organisation<br />

that was fully established in 2000 in-line with the national umbrella organisation<br />

Community Recycling Network UK which promotes community-based sustainable waste<br />

management. The LCRN supports and represents <strong>London</strong>’s voluntary and community<br />

groups working in the recycling sector (‘Community Recyclers’). Community Recyclers<br />

assist local authorities in meeting their household waste recycling and composting<br />

targets. LCRN works with municipal and commercial sectors in four main areas:<br />

• Recycling – collection and recycling of household and commercial dry recyclables<br />

• Composting – providing services and support for composting of organic waste<br />

• Re-use – target manufactured goods that can be refurbished, repaired or<br />

reprocessed<br />

• Reduction – providing services and support for minimising waste<br />

3.22. The <strong>London</strong> Boroughs in their role as waste collection authorities also clearly have a<br />

key role, or potential role, in promoting sustainable waste management to those<br />

businesses that they service and work with.<br />

3.23. The current and planned activities of these various bodies are returned to in more detail<br />

in the next Chapter.<br />

18

4. Commercial and Industrial <strong>Waste</strong><br />

Introduction<br />

4.1. The aim of this part of the project was to evaluate the current management strategies<br />

for commercial and industrial wastes in <strong>London</strong>, building upon the existing knowledge<br />

base, to enable and inform the development of appropriate policies within the context<br />

of a wider strategy for this waste stream. The specific objectives are listed below. A<br />

summary of the key findings from this chapter is presented in Chapter 7.<br />

Identify and engage with key stakeholders, to include:<br />

• Consultation with the waste management companies operating in <strong>London</strong> to review commercial<br />

and industrial collection and disposal contracts in place, specifically in terms of tonnages,<br />

management, and customer range (with regard to sectors).<br />

• Consultation with <strong>London</strong> Local Authorities offering commercial waste collection services, to<br />

establish tonnages, management, and customer range (with regard to sectors), and where<br />

possible establish future intentions with regard to the provision of this service.<br />

• Evaluation of sector based activity, utilizing existing data sources to: identify sectors that are<br />

most prolific in <strong>London</strong>; engage with relevant stakeholders, government bodies and Trade<br />

Associations to review their sectors waste generation and management; establish whether<br />

projections can be made, or should be made, in terms of specific growth areas, major employers,<br />

or sectors targeted by legislation and policy with regard to waste management.<br />

• Evaluation of SME activity in <strong>London</strong>, developing a profile of the size of this sector, waste<br />

generation and management options.<br />

• Assessment of different measures taken by Local Authorities to prevent mixing of household<br />

and commercial waste and make recommendations of good practice.<br />

• Assessment of the effectiveness to date and potential applicability of specific measures and<br />

instruments to promote waste minimisation, recycling and diversion from landfill, to include:<br />

– the current and potential role of waste exchanges in <strong>London</strong> and the potential opportunities<br />

available through the promotion of industrial symbiosis;<br />

– the role and impacts of waste minimisation clubs;<br />

– the use of environmental reporting;<br />

– the impact of the Mayor’s Green Procurement Code;<br />

– the use of standards (for example international standards, such as ISO 14001, or national/locally<br />

applied product standards).<br />

4.2. This chapter starts with an overview of the approach that we have used for researching<br />

and analysing commercial and industrial wastes. We then present a literature review of<br />

the background information that has been collected and collated for this chapter. There<br />

then follows three sections on consultations, starting with waste management<br />

companies, then recyclers and reprocessors, and finally with regard to waste transport<br />

by water. We then focus on commercial and industrial wastes from the perspective of<br />

the size of enterprise producing them, first by looking at small and medium sized<br />

enterprises (SMEs) 10 and then large companies, before going on to consider the drivers<br />

for sustainable waste management practices and aids to assist best practice.<br />

10 SMEs are defined as companies with less than 250 employees.<br />

19

4.3. There then follows a section of further analysis where we have applied compositional<br />

data on commercial and industrial arisings to provide an estimate on the likely<br />

composition of the main commercial waste streams. Finally, we have undertaken<br />

consultations with local authorities with regard to their collection and disposal of<br />

commercial and industrial wastes.<br />

Method<br />

4.4. Relevant literature on commercial and industrial wastes in <strong>London</strong> has been collected<br />

and collated. A literature review was then undertaken to appraise existing information<br />

of relevance to the study and identify concerns and gaps which need to be addressed to<br />

meet the requirements of the brief. These gaps were then addressed through further<br />

research and consultations with waste management companies, research organisations,<br />

local authorities, and the Environment Agency.<br />

4.5. A major part of this study has been based on consultations. This is particularly the case<br />

for this chapter on commercial and industrial wastes. We have approached numerous<br />

companies, public sector agencies, organisations and the <strong>London</strong> Boroughs. The<br />

timescale for the consultations has been very tight and we have often asked for detailed<br />

discussions and information from consultees, all of which has required their close<br />

attention. In the vast majority of cases, the response from consultees has been<br />

extremely helpful and positive. We would like to take this opportunity to thank all of<br />

those consultees that we approached for their time and input into this project. We very<br />

much value these contributions and acknowledge that this project would not have been<br />

possible without their support. A full list of consultees for this chapter is provided in<br />

Appendix B.<br />

4.6. When compiling this report, we have tried to aggregate comments from consultees to<br />

protect commercially sensitive information, as well as to provide an overall profile of<br />

wider wastes in <strong>London</strong>. In doing so we trust that we have accurately reflected<br />

consultees comments. Whilst we have consulted with all the organisations that we<br />

originally intended, it is important to note that this report sets out anecdotal<br />

information and opinion from those consultees that wanted to respond only. We are<br />

aware that there may be others who would have liked to have been approached, but we<br />

were precluded from making contacts due to time and resources restrictions.<br />

Literature Review<br />

4.7. This section provides a literature review of the main documents collected and collated at<br />

the start of this study. It is presented document by document.<br />

‘Strategic <strong>Waste</strong> Management Assessment, <strong>London</strong> (SWMAL), 2000’,<br />

Environment Agency<br />

4.8. This report, compiled by the Environment Agency (EA), is based on two data sources:<br />

• DEFRA Municipal <strong>Waste</strong> Survey of 1998/99 (formerly the DETR survey);<br />

• EA National <strong>Waste</strong> Production Survey of 1998/99 (includes C&I, C&D and<br />

hazardous wastes).<br />

4.9. The DEFRA survey is based on data from questionnaires sent to all <strong>Waste</strong> Collection<br />

Authorities (WCAs), <strong>Waste</strong> Disposal Authorities (WDAs) and Unitary Authorities in<br />

England. Information was collected from each local authority including:<br />

• the amounts of municipal waste collected and disposed of;<br />

20

• the levels of recycling and recovery of household and municipal waste;<br />

• the methods of waste containment;<br />

• levels of service provision; and,<br />

• waste collection and disposal contracts.<br />

4.10. All <strong>London</strong> waste authorities now send their completed questionnaires to the <strong>Greater</strong><br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Authority</strong>, which validates and publishes the data on the capitalwastefacts.com<br />

website.<br />

4.11. The National <strong>Waste</strong> Production Survey was undertaken by the Environment Agency in<br />

1999, and is believed to be the largest and most comprehensive study of its kind in<br />

Europe. 20,000 companies were contacted, with 18,600 providing responses, including<br />

more than 1200 from <strong>London</strong>. Each company was asked to provide information on:<br />

• types of waste;<br />

• quantity of waste;<br />

• mixed, special or packaging waste;<br />

• waste form – solid, liquid or sludge;<br />

• waste disposal (or recovery) method;<br />

• the cost of disposal or income from recovery;<br />

• Standard Industrial Classification (SIC);<br />

• number of employees;<br />

• location; and,<br />

• environmental performance.<br />

4.12. The SWMAL provides baseline data for waste arisings, movements and management<br />

methods for commercial and industrial waste produced in <strong>London</strong>. The main finding<br />

was that an estimated 7.1 million tonnes of industrial and commercial waste was<br />

produced in <strong>London</strong> 1998/99, with 61% from commercial activities and 39% from<br />

industrial sectors. Of this 7 million tonnes, at least 84% was exported out of <strong>London</strong> for<br />

disposal or recovery. These figures are summarised in Table 4.1 below.<br />

4.13. The SWMAL also provides a breakdown of the various types of commercial and<br />

industrial wastes generated within different industrial and commercial sectors. From<br />

Table 4.1 it can be seen that some 60% of the C&I waste in <strong>London</strong> (4.211 million<br />

tonnes) is simply classified as ‘general industrial and commercial waste’. Further,<br />

another 13% (941,000 tonnes) is put into other general categories, i.e. ’other general<br />

and biodegradable’ and ‘contaminated general’. In addition, the ‘inert/C&D’ waste<br />

stream of 152,000 tonnes (2%) could include a wide range of wastes.<br />

21

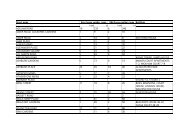

Table 4.1: Arisings and basic composition of industrial and commercial waste<br />

produced in <strong>London</strong> (000s tonnes) (from EA National <strong>Waste</strong> Production Survey<br />

1998-99)<br />

<strong>Waste</strong> Type Industry<br />

(k tpa)<br />

Commerce<br />

(k tpa)<br />

Total<br />

(k tpa)<br />

%<br />

<strong>London</strong><br />

% England<br />

& Wales<br />

Inert/C&D 104 48 152 2.1 6.4<br />

Paper and<br />

card<br />

378 454 832 11.7 15.9<br />

Food 174 61 235 3.3 9.1<br />

General<br />

industrial &<br />

commercial<br />

Other general<br />

&<br />

biodegradable<br />

Metals &<br />

scrap<br />

equipment<br />

Contaminated<br />

general<br />

Mineral<br />

wastes &<br />

residues<br />

Chemical &<br />

other<br />

1,003 3,208 4,211 59.4 14.9<br />

360 313 673 9.5 7.7<br />

140 86 226 3.2 4.7<br />

154 114 268 3.8 6.7<br />

27 4 31 0.4 0.2<br />

400 62 462 6.5 7.8<br />

TOTAL 2740(39%) 4,350(61%) 7,090 99.9 9.5<br />

4.14. Whilst an indication of source and/or composition is provided in Table 4.1 for a number<br />

of waste streams (i.e. paper and card; food; metals and scrap equipment; mineral<br />

wastes and residues; chemical and other), together these account for just 1.8 million<br />

tonnes or 25% of the total commercial and industrial waste stream. Hence, the SWMAL<br />

provides relatively little information on the waste stream or its composition for the<br />

majority (i.e. 75%) of commercial and industrial wastes arising in <strong>London</strong>.<br />

4.15. The Strategic <strong>Waste</strong> Management Assessment for <strong>London</strong> also gives information on the<br />

movement of commercial and industrial waste within the Environment Agency <strong>London</strong><br />

sub-region (see Table 4.2). However, the majority (67%) of the movement is<br />

unrecorded. Table 4.2 indicates that of the commercial and industrial waste for which<br />

the destination is recorded, 378,000 tonnes (i.e. 5% of the total) is managed within<br />

<strong>London</strong> and 1,950,000 tonnes (28% of the total) is managed outside the city. Results<br />

from the inter-regional waste movement study between the East of England, South East<br />

22

and <strong>London</strong> regions currently being undertaken by M.E.L Research should assist in<br />

providing a clearer picture of the amount of commercial and industrial waste that is<br />

managed outside of <strong>London</strong>.<br />

Table 4.2: Commercial and Industrial <strong>Waste</strong> Flows (from SWMA <strong>London</strong>, 2000)<br />

Environment<br />

Agency<br />

Sub-region<br />

Central<br />

<strong>London</strong><br />

Destination of C&I material (000 tonnes)<br />

Central E N SE S W WRWA Outside<br />

City<br />

Unrecorded<br />

Total<br />