25 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

25 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

25 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

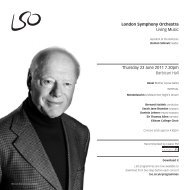

Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

Resident at the Barbican<br />

Roman Simovic leader<br />

Saturday <strong>25</strong> <strong>September</strong> 2010 7.30pm<br />

Barbican Hall<br />

Bizet arr Rodion Shchedrin Carmen Suite<br />

Rodion Shchedrin Piano Concerto No 5<br />

INTERVAL<br />

Mussorgsky orch Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition<br />

Valery Gergiev conductor<br />

Denis Matsuev piano<br />

Concert ends approx 9.55pm<br />

Recommended by Classic FM<br />

Recorded for broadcast on Wednesday 29 <strong>September</strong> on BBC Radio 3

Welcome News<br />

A very warm welcome to the LSO’s opening concert of the 2010/11<br />

season, conducted by LSO Principal Conductor Valery Gergiev. We are<br />

delighted to be back at our Barbican home after a summer of highly<br />

successful concerts in the UK and abroad, including at the BBC Proms,<br />

in Aix-en-Provence and in Germany, and a major tour to China.<br />

Tonight’s concert begins with two works by the Russian composer<br />

Rodion Shchedrin: a composer much admired by Valery Gergiev and<br />

one whose music Gergiev has been eager to share with <strong>London</strong><br />

audiences for some time. We are delighted and honoured that<br />

Shchedrin is able to be with us in the audience tonight, and look<br />

forward to hearing more of his music later in the season.<br />

Tonight we also welcome our piano soloist Denis Matsuev, who will<br />

perform Shchedrin’s Piano Concerto No 5. This is Matsuev’s second<br />

visit to the LSO following his highly-acclaimed debut in March 2010.<br />

On behalf of everyone at the LSO I would like to extend my thanks<br />

to our media partners BBC Radio 3, who are recording this concert<br />

for broadcast on 29 <strong>September</strong>, and to Classic FM for their<br />

continued support.<br />

I hope you enjoy this evening’s performance and that you will be<br />

able to join us for many more concerts this season!<br />

Kathryn McDowell<br />

LSO Managing Director<br />

BBC Radio 3 Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s<br />

A new series of chamber concerts begins at LSO St Luke’s this<br />

autumn, starting with solo recitals of Chopin piano music by Sergio<br />

Tiempo (30 Sep), Nicholas Angelich (7 Oct) and Benjamin Grosvenor<br />

(14 Oct). Later in the autumn we’ll welcome former BBC New<br />

Generation Artists the Pavel Haas Quartet, who will perform string<br />

quartets by Dvořák, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel and Schubert.<br />

All concerts begin at 1pm. Call 020 7638 8891 to book (tickets £9),<br />

or book online.<br />

lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts<br />

Musical events for everyone from LSO Discovery<br />

LSO Discovery have lots of events planned to kick off the autumn<br />

season. As well as the regular groups for all ages, from the Early<br />

Years Workshops to our Youth and Community choirs and our Digital<br />

Technology Group, there’s a chance to hear violinist Viktoria Mullova<br />

– the subject of our LSO Artist Portrait this season – in conversation<br />

at LSO St Luke’s on Friday 1 October. In discussion with LSO players,<br />

and illustrated by practical demonstrations, Viktoria will focus on her<br />

transition from Russian to Baroque repertoire. Or find out more<br />

about Czech composer Leoš Janáček at a Discovery Day on Sunday<br />

10 October, including access to an LSO rehearsal, a talk, chamber<br />

music and the chance to meet LSO players. For more ideas and<br />

information, visit<br />

lso.co.uk/getinvolved<br />

There's never been a better time to bring your friends to an<br />

LSO concert. Groups of 10+ receive a 20% discount on all tickets,<br />

plus a host of additional benefits. Call the dedicated Group Booking<br />

line on 020 7382 7211, visit lso.co.uk/groups, or email<br />

groups@barbican.org.uk.<br />

The LSO is delighted to welcome Classical Partners tonight.<br />

Bizet arr Rodion Shchedrin (b 1932)<br />

Carmen Suite (1967)<br />

Introduction<br />

Dance<br />

First Intermezzo<br />

Changing of the Guard<br />

Carmen’s Entrance and Habanera<br />

Scene<br />

Second Intermezzo<br />

Bolero<br />

Torero<br />

Torero and Carmen<br />

Adagio<br />

Fortune-telling<br />

Finale<br />

Ever since Oscar Hammerstein II and Richard Rodney Bennett<br />

collaborated on Carmen Jones in 1943, the idea of adapting Bizet’s<br />

opera to different media has been irresistibly attractive. In the world<br />

of ballet it started in 1949 with Roland Petit for Les Ballets de Paris,<br />

in a production that premiered in <strong>London</strong>. Seemingly unaware of<br />

that version, it had long been the dream of Shchedrin’s wife, the<br />

celebrated prima ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, to dance the title role.<br />

At one stage she even went to Shostakovich with the proposal,<br />

but despite their friendship he refused, on the grounds that it was<br />

impossible to compete with Bizet’s music. A similar response came<br />

from Aram Khachaturian, of Spartacus fame.<br />

Then in 1966 the Cuban National Ballet visited Moscow. Their<br />

passionate style worked on Plisetskaya, so she later said, like a snakebite.<br />

More calculatedly, she realised that a potential collaboration with<br />

virtually the only functioning communist regime in the West might<br />

conceivably gain approval from the Soviet powers-that-be, and she<br />

persuaded the Ministry of Culture to commission a Carmen ballet.<br />

Choreographer Alberto Alonso came up with a politically correct<br />

scenario, in which Carmen would be the victim of ‘a totalitarian<br />

system of universal slavery and submission’, and since time was<br />

short, Shchedrin produced a persiflage of Bizet rather than an<br />

original composition, with all sorts of additional colours and minor<br />

adjustments based on Alonso’s stipulations for drama and pacing.<br />

In the course of 20 days, four of which were spent in Hungary at<br />

the funeral of Zoltán Kodály, the composer ran up a score for strings<br />

and percussion that has since become a favourite in the concert<br />

hall. Plisetskaya herself would go on to dance the role some 350<br />

times, despite having to fight to reverse an official ban after the first<br />

performance (it seems that even as late as 1967 the Bolshoi Theatre<br />

and its political masters had problems with the spectacle of bare<br />

thighs and entwined legs).<br />

In addition to all the favourite tunes from the opera, the 13-movement<br />

Suite borrows two numbers from Bizet’s incidental music to<br />

L’Arlésienne and one from his opera La Jolie Fille de Perth. Shchedrin’s<br />

writing for percussion is the essential ingredient in his translation of<br />

the score, initially to comic-satirical effect, but with ever-increasing<br />

seriousness. If his model was, perhaps, the extraordinary percussion<br />

coda to the second movement of Shostakovich’s Fourth <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

– at that time recently rehabilitated in the Soviet Union – the debt<br />

would be handsomely repaid when Shostakovich composed his 14th<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> two years later, scored for strings and percussion and with<br />

even a Carmen-ish ‘Malagueña’ as its second movement.<br />

The Introduction to Shchedrin’s Suite steals in as though in a<br />

dream, with tubular bells and col legno strings apparently sensing<br />

impending doom. Then a succession of numbers illustrates the wit<br />

and verve of the scoring, almost as if the composer is imagining a<br />

rebellious orchestra determined to subvert a rehearsal of the opera.<br />

Woodblocks, cowbells and bongos add their wry comments to<br />

‘Changing of the Guard’, insinuating an extra beat before allowing<br />

the music to play ‘straight’. And who could resist the sexy güiro or<br />

the sinuous vibraphone in the famous Habanera, or the sudden<br />

withholding of the theme in the Toreador’s movement?<br />

Already by this stage the hand of Fate has been sensed, and<br />

Bizet’s leitmotiv takes over in the Adagio, the movement whose<br />

choreography had most offended officialdom at the premiere.<br />

Shchedrin plays no tricks with the tragic dénouement, and the Suite<br />

ends as it began, except that, as we know, premonitions have now<br />

been fulfilled.<br />

2 Welcome & News Kathryn McDowell © Camilla Panufnik Programme Notes 3

Rodion Shchedrin (b 1932)<br />

Piano Concerto No 5 (1999)<br />

Allegretto moderato<br />

Andante<br />

Allegro assai<br />

Denis Matsuev piano<br />

Since Prokofiev and Shostakovich, the number of front-rank<br />

composers who could also claim to be first-rate concert pianists has<br />

dwindled remarkably, and of the remaining few, hardly any have made<br />

piano music as strong a feature of their output as Rodion Shchedrin.<br />

Trained as a composer under Yuri Shaporin and as a pianist under<br />

Yakov Flier, he has composed six piano concertos to date, as well as a<br />

substantial body of solo piano works.<br />

In this area Shchedrin has generally shown more affinity for Prokofiev<br />

than for Shostakovich, especially the concertos, which at least initially<br />

were marked by vivid colours, forceful energy and total absence of<br />

self-doubt. His First Piano Concerto, for instance, a graduation piece<br />

from 1954, was a cheerfully extrovert romp that could have been<br />

designed as a tribute to Prokofiev, who had died the previous year.<br />

Twelve years later, the Second Concerto retained that influence,<br />

alongside a playful indulgence in twelve-note techniques.<br />

However, nearly 20 years separate the first three piano concertos,<br />

all of which Shchedrin premiered and recorded with himself as soloist,<br />

from the last three (No 3 was composed in 1973, No 4 in 1991).<br />

In this second phase, exhibitionism gives way to a more private,<br />

exploratory tone.<br />

The Fifth Piano Concerto was composed in 1999 for Finnish pianistcomposer<br />

Olli Mustonen, who gave the premiere in October that<br />

year with the Los Angeles Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong> under Esa-Pekka<br />

Salonen. Indeed the first movement seems initially designed to<br />

showcase Mustonen’s trademark pecking staccato touch, which is set<br />

off firstly against slow, singing lines, then against attractively scored<br />

scalic flourishes. The extended central section is slightly slower as<br />

well as weightier in tone, and it eventually inspires a more songful<br />

transformation of the opening material. This lengthy movement closes<br />

with a brief return of textures from the first section.<br />

4 Programme Notes<br />

The slow movement opens with an austere orchestral chorale, which<br />

the piano immediately takes up in a short cadenza. Ghosts of the first<br />

movement pass across the stage, but the main musical character<br />

seems to focus on four-note descending figures, highly malleable<br />

but almost always song-like.<br />

In essence a perpetuum mobile, the finale deliberately emulates<br />

the ‘crescendo with music’ of Ravel’s Bolero. For long stretches this<br />

movement demands greater virtuosity from the orchestra than the<br />

soloist, at least in terms of rhythmical precision. Finally the soloist cuts<br />

loose in a cadenza worthy of Shostakovich for its manic leaps, and<br />

when the orchestra rejoins it is with a Prokofievian style mécanique in<br />

overdrive, concluding the work with its most physically exciting pages.<br />

Shchedrin <strong>programme</strong> notes and profile © David Fanning<br />

David Fanning is a professor of music at the University of Manchester.<br />

He is an expert on Shostakovich, Nielsen and Soviet music. He is also<br />

a reviewer for the Daily Telegraph, Gramophone and BBC Radio 3.<br />

INTERVAL: 20 minutes<br />

I still today continue to be convinced that<br />

the decisive factor for each composition is<br />

intuition. As soon as composers relinquish<br />

their trust in this intuition and rely in its<br />

place on musical ‘religions’ such as serialism,<br />

aleatoric composition, minimalism or<br />

other methods, things become problematic.<br />

Rodion Shchedrin<br />

Rodion Shchedrin (b 1932)<br />

The Man<br />

The generation of Soviet composers after Shostakovich produced<br />

charismatic and exotic figures such as Galina Ustvolskaya,<br />

Alfred Schnittke and Sofiya Gubaydulina, whose music was initially<br />

controversial but then gained cult status. At the other end of the<br />

stylistic spectrum it featured highly gifted craftsmen such as<br />

Boris Tishchenko, Boris Tchaikovsky and Mieczysław Weinberg, all<br />

of whom worked more or less within the parameters laid down by<br />

Shostakovich and were highly respected in their heyday but gradually<br />

fell from favour.<br />

Somewhere in between we can locate Rodion Shchedrin – an<br />

individualist with a broader and more consistent appeal, who could<br />

turn himself chameleon-like to virtuoso pranks or to profound<br />

philosophical reflection, to Socialist Realist opera or to folkloristic<br />

Concertos for <strong>Orchestra</strong> (a particular speciality), to technically solid<br />

Preludes and Fugues, to jazz, and, when he chose, even to twelvenote<br />

constructivism.<br />

Trained at the Moscow Conservatoire in the 1950s, as a composer<br />

under Yuri Shaporin and as a pianist under Yakov Flier in the early<br />

years of the Post-Stalinist Thaw, Shchedrin was one of<br />

the first to speak out against the constraints of<br />

musical life in the Soviet Union. He went on to play<br />

a significant administrative role in the country’s<br />

musical life, heading the Russian Union of Composers<br />

from 1973 to 1990. Married since 1958 to the star<br />

Soviet ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, he established a<br />

significant power-base from which he was able to promote<br />

not only his own music but also that of others – such as<br />

Schnittke, whose notorious First <strong>Symphony</strong> received its<br />

sensational premiere only thanks to Shchedrin’s support.<br />

An unashamed eclectic, and suspicious of dogma from<br />

either the arch-modernist or arch-traditionalist wings of<br />

Soviet music, Shchedrin occupied a not always comfortable<br />

position, both in his pronouncements and in his creative<br />

work. With one foot in the national-traditional camp and the<br />

other in that of the internationalist-progressives, he was<br />

tagged with the unkind but not unfair label of the USSR’s<br />

Rodion Shchedrin © www.lebrecht.co.uk<br />

‘official modernist’. From 1992 he established a second home in<br />

Munich, but he still enjoyed official favour in post-Soviet Russia,<br />

adding steadily to his already impressive roster of prizes.<br />

Shchedrin has summed up his artistic credo as follows: ‘I continue to<br />

be convinced that the decisive factor for each composition is intuition.<br />

As soon as composers relinquish their trust in this intuition and rely in<br />

its place on musical ‘religions’ such as serialism, aleatoric composition,<br />

minimalism or other methods, things become problematic.’<br />

Programme Notes<br />

5

Rodion Shchedrin & Valery Gergiev<br />

Russian Compatriots<br />

Rodion Shchedrin<br />

Valery Gergiev<br />

16 Dec 1932<br />

Born, Moscow<br />

6 Programme Notes<br />

1945–50<br />

Joined the<br />

Moscow<br />

Choral School<br />

1950–55<br />

Trained at<br />

the Moscow<br />

Conservatory<br />

1958<br />

Married<br />

ballerina Maya<br />

Plisetskaya<br />

2 May 1953<br />

Born, Moscow<br />

Valery Gergiev’s Rodion Shchedrin<br />

1960<br />

The Little<br />

Humpbacked<br />

Horse, Moscow<br />

1961<br />

Not only love,<br />

Moscow<br />

1963<br />

Naughty Limericks,<br />

Warsaw<br />

Fri 19 Nov 2010 Piano Concerto No 4 (‘Sharp Keys’) with Olli Mustonen<br />

Wed 23 & Thu 24 Mar 2011 Lithuanian Saga<br />

1964–69<br />

Professor of Composition,<br />

Moscow Conservatory<br />

1967<br />

Carmen Suite,<br />

Moscow<br />

1968<br />

The Chimes,<br />

New York<br />

1969<br />

Becomes freelance<br />

composer<br />

1968<br />

Refused to sign open<br />

letter sanctioning the<br />

invasion of Warsaw Pact<br />

troops in Czechoslovakia<br />

1972<br />

Anna Karenina,<br />

Moscow<br />

1973<br />

Succeeds Shostakovich<br />

as President of the Union<br />

of Composers of the<br />

Russian Federation<br />

1972<br />

Receives the USSR<br />

State Prize<br />

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000<br />

1972–77<br />

Trained at the Leningrad<br />

Conservatory<br />

1977<br />

Dead Souls,<br />

Moscow<br />

1976<br />

Wins Herbert von Karajan<br />

Conducting Competition,<br />

Berlin<br />

1977<br />

Appointed Assistant<br />

Conductor to Kirov<br />

Opera<br />

1978<br />

Kirov debut<br />

– War and<br />

Peace<br />

1981–85<br />

Appointed Chief<br />

Conductor of the<br />

Armenian Philharmonic<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

1989<br />

Khorovody,<br />

Tokyo<br />

1985<br />

Honorary member of the<br />

International Music Council<br />

1983<br />

Honorary member of the<br />

Academy of Fine Arts, GDR<br />

1984<br />

Receives the Lenin Prize<br />

1985<br />

UK debut at the<br />

Lichfield Festival<br />

1988<br />

The Sealed<br />

Angel,<br />

Moscow<br />

1988<br />

LSO debut<br />

1989<br />

Member of Berlin<br />

Arts Academy<br />

1988<br />

Appointed Chief<br />

Conductor and<br />

Artistic Director<br />

of the Mariinsky<br />

Theatre<br />

1990<br />

Old Russian Circus<br />

Music, Chicago<br />

1991<br />

USA debut with<br />

War and Peace<br />

1994<br />

Lolita, Stockholm;<br />

Sotto voce Concerto,<br />

<strong>London</strong>;<br />

Trumpet Concerto,<br />

Pittsburgh<br />

1993<br />

Receives Dmitri<br />

Shostakovich Prize<br />

1998<br />

Four Russian Songs,<br />

<strong>London</strong><br />

1997<br />

Honorary Professor,<br />

Moscow Conservatory<br />

1997<br />

Receives Dmitri<br />

Shostakovich Prize<br />

1998<br />

Fifth Piano Concerto,<br />

Los Angeles<br />

1999<br />

Marries Natalya Debisova<br />

1995–2008<br />

Appointed Principal Conductor<br />

of the Rotterdam Philharmonic<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

1996<br />

Russian government appoints<br />

him overall Director of the<br />

Mariinsky Theatre<br />

1997<br />

Appointed Principal Guest<br />

Conductor of the Metropolitan<br />

Opera, New York<br />

2002<br />

Dialogues with<br />

Shostakovich,<br />

Pittsburgh<br />

2003<br />

Sixth Piano Concerto,<br />

Amsterdam<br />

2002<br />

Order for Service to<br />

the Russian State:<br />

Third Degree<br />

2005<br />

2008<br />

Honorary Professor, Honorary Professor,<br />

St Petersburg State Central Conservatory<br />

Conservatory of Music, Beijing<br />

2003<br />

UNESCO Artist for Peace<br />

2003<br />

Order for Service to the<br />

Russian State: Third Degree<br />

2003<br />

First performance<br />

of Wagner’s Ring in<br />

Russia for 90 years<br />

2006<br />

Boyarina Morozova,<br />

Moscow<br />

2007<br />

Order for Service to<br />

the Russian State:<br />

Fourth Degree<br />

2006<br />

Opens the new<br />

Mariinsky Concert<br />

Hall<br />

2008<br />

Order for Service to<br />

the Russian State:<br />

Fourth Degree<br />

2004<br />

2007<br />

Second appearance Takes Mariinsky<br />

with the LSO Wagner’s Ring to<br />

New York<br />

2005<br />

Appointed 15th Principal<br />

Conductor of the LSO<br />

(first official concert<br />

23 Jan 07)<br />

2010<br />

Named one of the 100 Most<br />

Influential People in the World<br />

by Time magazine<br />

Programme Notes<br />

7

Modest Mussorgsky (1839–81) orch Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)<br />

Pictures at an Exhibition (1874 orch 1922)<br />

Promenade<br />

1 Gnomus<br />

Promenade<br />

2 Il vecchio castello<br />

Promenade<br />

3 Tuileries (Dispute d’enfants après jeux)<br />

4 Bydło<br />

Promenade<br />

5 Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks<br />

6 Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle<br />

7 Limoges: Le marché (La grande nouvelle) –<br />

8 Catacombae (Sepulchrum romanum) –<br />

Cum mortuis in lingua morta<br />

9 The Hut on Hen’s Legs (Baba Yaga) –<br />

10 The Great Gate of Kiev<br />

Victor Hartmann’s promising career as an architect, painter, illustrator<br />

and designer was cut short by his death at the age of 39 in 1873.<br />

In February 1874 there was a memorial exhibition of his work in<br />

St Petersburg, and this was the stimulus for Mussorgsky to compose<br />

his piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition to the memory of his dead friend.<br />

The Hartmann exhibition contained 400 items. Only a quarter of them<br />

have survived, and of these only six relate directly to Mussorgsky’s<br />

music. Among the lost works are the inspirations behind Gnomus,<br />

Bydło, Tuileries, Il vecchio castello and Limoges. This hardly matters,<br />

though, because Mussorgsky’s imagination goes far beyond the<br />

immediate visual stimulus. It tells us little about the music to learn that<br />

the half-sinister, half-poignant Gnomus was inspired by a design for a<br />

nutcracker (you put the nuts in the gnome’s mouth), or that Baba Yaga<br />

was a harmless and fussy design for a clock, hard to connect with<br />

Mussorgsky’s powerful witch music. Goldenberg and Schmuÿle are<br />

actually two separate drawings, and the dialogue between them is an<br />

invention of the composer’s.<br />

Mussorgsky, a song composer of genius, could sum up a character,<br />

mood or scene in brief, striking musical images, and this is what he<br />

does in Pictures. The human voice is never far away: Bydło, a picture<br />

of a lumbering ox-cart, and Il vecchio castello (The Old Castle) could<br />

well be songs; some of the Promenades and The Great Gate of Kiev<br />

suggest the choral tableaux in his operas; in Goldenberg and Schmuÿle,<br />

the differences between the rich Jew and the poor Jew are suggested<br />

by their different ‘speech patterns’; in Tuileries we hear the cries of<br />

children playing and in Limoges the squabbling of market-women.<br />

Pictures might have been just a loose collection of pieces, but<br />

Mussorgsky in fact devised something far more complex and<br />

interesting. The Promenade that links the pictures is on one level a<br />

framing device, representing the composer (or perhaps the listener)<br />

walking around the exhibition. Sometimes he passes directly from one<br />

picture to another, without reflection. Sometimes he is lost in thought.<br />

On one occasion, he seems to be distracted by seeing something out<br />

of the corner of his eye (the false start to the Ballet of the Unhatched<br />

Chicks), and turns to look more closely. Cum mortuis is not itself a<br />

picture, but represents the composer’s reflections on mortality after<br />

seeing the drawing of Hartmann and two other figures surrounded<br />

by piles of skulls in the Paris catacombs. The composer is also drawn<br />

personally into the final picture as the Promenade emerges grandly<br />

from the texture of The Great Gate of Kiev.<br />

Although Mussorgsky must have played Pictures to his friends, there<br />

is no record of any public performance until well into the 20th century.<br />

It was indeed only after the success of Ravel’s orchestration that<br />

performances of the piano version became at all common. The piano<br />

writing of Pictures is often said to be unidiomatic, and Mussorgsky<br />

certainly never cared for conventional beauty of sound or pianistic<br />

virtuosity for its own sake. There are certainly aspects of the texture<br />

that are hard to bring off successfully, such as the heavy chordal style<br />

of some Promenades, Bydło and The Great Gate of Kiev; the tricky<br />

repeated notes in Goldenberg and Schmuÿle and Limoges; and the<br />

sustained tremolos in Cum mortuis and Baba Yaga. But these are all<br />

part of Mussorgsky’s desired effect.<br />

Pictures at an Exhibition has been subjected to many arrangements<br />

(including one by Proms founder-conductor Henry Wood), but none<br />

so brilliant as Ravel’s, which was commissioned by the Russian<br />

conductor Serge Koussevitzky, and first performed by him in Paris<br />

on 19 October 1922. Ravel was<br />

already a great enthusiast for<br />

the music of Mussorgsky. He had<br />

collaborated with Stravinsky on<br />

orchestrating parts of his opera<br />

Khovanshchina for Diaghilev’s<br />

Paris performances in 1913, and<br />

far preferred Mussorgsky’s barer<br />

original score of Boris Godunov<br />

to the more colourful edition by<br />

Rimsky-Korsakov. With Pictures<br />

there are only three major<br />

The Great Gate of Kiev differences between Ravel’s<br />

Victor Hartmann<br />

orchestration and the piano<br />

original, which he knew only<br />

from Rimsky’s 1886 edition: the omission of a Promenade between<br />

Goldenberg and Schmuÿle and Limoges; the addition of some extra<br />

bars in the finale; and the dynamics of Bydło, which Mussorgsky<br />

marked to begin loudly, not with a slow crescendo.<br />

Ravel’s orchestral colours and techniques are far more elaborate<br />

than anything that Mussorgsky might ever have conceived, so his<br />

work must be considered more a free interpretation than a simple<br />

transcription. Some of his choices of instrumentation for solo<br />

passages are unforgettable: the opening trumpet, for example, or<br />

the alto saxophone in Il vecchio castello and the tuba in Bydło.<br />

Even more remarkable is the range of colour that Ravel achieves, and<br />

the way in which the essence of the music is faithfully reproduced<br />

while the original piano textures are presented in an altogether<br />

different sound medium. Ravel and Mussorgsky could hardly have<br />

been more different as men and as composers, but Pictures at an<br />

Exhibition has justly become famous as a collaboration between two<br />

great creative minds.<br />

Programme note © Andrew Huth<br />

Andrew Huth is a musician, writer and translator who writes<br />

extensively on French, Russian and Eastern European music.<br />

Modest Mussorgsky (1839–81)<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Modest Mussorgsky was born in Karevo, the youngest son of a<br />

wealthy landowner. His mother gave him his first piano lessons, and<br />

his musical talent was encouraged at the Cadet School of the Guards<br />

in St Petersburg, where he began to compose (despite having no<br />

technical training) – in 1856, the year that he entered the Guards, he<br />

attempted an opera. In 1857 he met Balakirev, whom he persuaded<br />

to teach him, and shortly afterwards began composing in earnest.<br />

The following year Mussorgsky suffered an emotional crisis and<br />

resigned his army commission, but returned soon afterwards to<br />

his studies. He was, however, plagued by nervous tension, and this,<br />

combined with a crisis at the family home after the emancipation of<br />

the serfs in 1861, stalled his development quite severely. By 1863,<br />

though, he was finding his true voice, and he began to write an opera<br />

(never completed) based on Flaubert’s Salammbô. At this time he<br />

was working as a civil servant and living in a commune with five<br />

other young men passionate about art and philosophy, where he<br />

established his artistic ideals.<br />

In 1865 his mother died; this probably caused his first bout of<br />

alcoholism. His first major work, Night on Bare Mountain, was<br />

composed in 1867, and soon afterwards, fired by the ideas discussed<br />

in Balakirev’s circle (‘The Mighty Handful’) he began writing his opera<br />

Boris Godunov; a little later he also began work on another opera,<br />

Khovanshchina. Heavy drinking was once again affecting his creativity,<br />

though he did write the piano work Pictures at an Exhibition in a<br />

short time. By 1880 he was obliged to leave government employment,<br />

and despite the support of his friends, he lapsed still further,<br />

eventually being hospitalised in February 1881 after a bout of<br />

alcoholic epilepsy. It was during a brief respite that Repin painted his<br />

famous portrait of the composer, but within two weeks of that work,<br />

Mussorgsky died.<br />

Profile © Alison Bullock<br />

Alison Bullock is a freelance writer and music consultant whose<br />

interests range from Machaut to Messiaen and beyond. She is a<br />

former editor for the New Grove Dictionary of Music and the LSO.<br />

8 Programme Notes Programme Notes 9

Valery Gergiev<br />

Conductor<br />

Body<br />

Principal Conductor of the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> since January 2007, Valery Gergiev<br />

performs regularly with the LSO at the<br />

Barbican, at the Proms and at the Edinburgh<br />

Festival, as well as regular tours of Europe,<br />

North America and Asia. During the 2010/11<br />

season he will lead them in appearances in<br />

Germany, France, Switzerland, Japan and<br />

the USA.<br />

Valery Gergiev is Artistic and General<br />

Director of the Mariinsky Theatre, founder<br />

and Artistic Director of the Stars of the<br />

White Nights Festival and New Horizons<br />

Festival in St Petersburg, the Moscow Easter<br />

Festival, the Gergiev Rotterdam Festival, the<br />

Mikkeli International Festival, and the Red<br />

Sea Festival in Eilat, Israel. He succeeded<br />

Sir Georg Solti as conductor of the World<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> for Peace in 1998 and leads them<br />

this season in concerts in Abu Dhabi.<br />

His inspired leadership of the Mariinsky<br />

Theatre since 1988 has taken the Mariinsky<br />

ensembles to 45 countries and has brought<br />

universal acclaim to this legendary institution,<br />

now in its 227th season. Having opened a<br />

new concert hall in St Petersburg in 2006,<br />

Maestro Gergiev looks forward to the opening<br />

of the new Mariinsky Opera House in the<br />

summer of 2012.<br />

Born in Moscow, Valery Gergiev studied<br />

conducting with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad<br />

Conservatory. Aged 24 he won the Herbert<br />

von Karajan Conductors’ Competition in<br />

Berlin and made his Mariinsky Opera debut<br />

one year later in 1978 conducting Prokofiev’s<br />

War and Peace. In 2003 he led St Petersburg’s<br />

300th anniversary celebrations, and opened<br />

the Carnegie Hall season with the Mariinsky<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, the first Russian conductor to do<br />

so since Tchaikovsky conducted the Hall’s<br />

inaugural concert in 1891.<br />

Now a regular figure in all the world’s major<br />

concert halls, he will lead the LSO and<br />

the Mariinsky <strong>Orchestra</strong> in a symphonic<br />

Centennial Mahler Cycle in New York in the<br />

2010/11 season. He has led several cycles in<br />

New York including Shostakovich, Stravinsky,<br />

Prokofiev, Berlioz and Richard Wagner’s Ring.<br />

He has also introduced audiences to several<br />

rarely-performed Russian operas.<br />

Valery Gergiev’s many awards include a<br />

Grammy, the Dmitri Shostakovich Award,<br />

the Golden Mask Award, People’s Artist of<br />

Russia Award, the World Economic Forum’s<br />

Crystal Award, Sweden’s Polar Music Prize,<br />

Netherlands’s Knight of the Order of the Dutch<br />

Lion, Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun, Valencia’s<br />

Silver Medal, the Herbert von Karajan prize and<br />

France’s Royal Order of the Legion of Honour.<br />

He has recorded exclusively for Decca<br />

(Universal Classics), and appears also on<br />

the Philips and Deutsche Grammophon<br />

labels. Currently recording for LSO Live, his<br />

releases include Mahler Symphonies Nos<br />

1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8, Rachmaninov <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

No 2, Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet and Bartók<br />

Bluebeard’s Castle.<br />

His recordings on the newly formed Mariinsky<br />

Label are Shostakovich The Nose and<br />

Symphonies Nos 1, 2, 11 & 15, Tchaikovsky’s<br />

1812 Overture, Rachmaninov Piano Concerto<br />

No 3 and Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini,<br />

Shchedrin The Enchanted Wanderer,<br />

Stravinsky Les Noces and Oedipus Rex,<br />

many of which have won awards including<br />

four Grammy nominations. The most recent<br />

release is Wagner Parsifal (<strong>September</strong> 2010),<br />

featuring René Pape and Gary Lehman.<br />

Valery Gergiev conducts<br />

Fri 19 Nov 7.30pm<br />

Rodion Shchedrin Piano Concerto No 4<br />

(‘Sharp Keys’) with Olli Mustonen piano<br />

Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 1 (‘Titan’)<br />

Tue 18 & Sun 23 Jan 7.30pm<br />

Shostakovich Violin Concerto No 2<br />

with Sergey Khachatryan violin<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 1 (‘Winter<br />

Daydreams’)<br />

Wed 2 & Thu 3 Mar 7.30pm<br />

Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 9<br />

Tickets from £8<br />

lso.co.uk (£1.50 bkg fee per transaction)<br />

020 7638 8891 (£2.50 bkg fee per transaction)<br />

Denis Matsuev<br />

Piano<br />

Denis Matsuev has become a fast-rising<br />

star on the international concert stage<br />

since his triumphant victory at the Eleventh<br />

International Tchaikovsky Competition in<br />

Moscow in 1998, and has quickly established<br />

himself as one of the most sought-after<br />

pianists of his generation.<br />

Matsuev has collaborated with the world’s<br />

best known orchestras, such as the<br />

New York Philharmonic, Chicago <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

Berlin Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong>, <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>, <strong>London</strong> Philharmonic,<br />

Leipzig Gewandhaus <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Bavarian<br />

Radio <strong>Symphony</strong>, National <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

Pittsburgh <strong>Symphony</strong>, Cincinnati <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

WDR <strong>Symphony</strong> Cologne, BBC <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

Philharmonia <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Royal Scottish<br />

National <strong>Orchestra</strong>, Filarmonica della Scala,<br />

Orchestre National de France, Orchestre<br />

de Paris, Orchestre Philharmonique de<br />

Radio France, Orchestre National du<br />

Capitole de Toulouse, Budapest Festival<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, Rotterdam Philharmonic, and<br />

the European Chamber <strong>Orchestra</strong>; he is<br />

continually engaged with the legendary<br />

Russian orchestras such as the St Petersburg<br />

Philharmonic, the Mariinsky <strong>Orchestra</strong> and<br />

the Russian National <strong>Orchestra</strong>.<br />

Denis Matsuev’s worldwide festival<br />

appearances include Leipzig’s Mendelssohn<br />

and Schumann Festival, the Chopin Festival<br />

in Poland, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino and<br />

the Mito Festival, both in Italy, Les Chorégies<br />

d’Orange in France, Verbier Festival in<br />

Switzerland, Enescu Festival in Romania and<br />

the Ravinia Festival in the USA.<br />

In the 2010/11 season, Denis Matsuev will<br />

appear under the batons of Valery Gergiev,<br />

Paavo Järvi (Orchestre de Paris and Frankfurt<br />

Radio <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>), Kurt Masur<br />

(Orchestre National de France), Zubin Mehta<br />

(<strong>Orchestra</strong> del Maggio Musicale Florentino),<br />

Mikhail Pletnev (Philharmonia <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

Russian National <strong>Orchestra</strong>), Vladimir<br />

Spivakov (National Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

of Russia in France and Russia), and Yuri<br />

Temirkanov (Philharmonia <strong>Orchestra</strong>, and<br />

St Petersburg Philharmonic in Taiwan,<br />

Shanghai, Beijing and Hong Kong).<br />

In 2011 he will also return to the Pittsburgh<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> with Gianandrea Noseda, and<br />

will undertake a North American recital<br />

tour including Boston, Washington, Toronto,<br />

Montreal, Vancouver and San Francisco.<br />

In December 2007, Sony BMG released a CD<br />

of Matsuev: Unknown Rachmaninoff, and<br />

garnered strong positive reviews praising<br />

his execution and creativity. His Carnegie<br />

Hall debut recital in 2007 was recorded live<br />

by Sony BMG: Denis Matsuev – Concert<br />

at Carnegie Hall. In December 2009, the<br />

new Mariinsky Label released Matsuev’s<br />

Rachmaninov Concerto No 3, with Valery<br />

Gergiev and the Mariinsky <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

recorded in the Mariinsky Concert Hall in<br />

St Petersburg.<br />

Over the past four years, Denis Matsuev has<br />

collaborated with the Sergei Rachmaninov<br />

Foundation and its President, Alexander<br />

Rachmaninov, the grandson of the composer.<br />

He was chosen by the Foundation to perform<br />

and record unknown pieces by Rachmaninov<br />

on the composer’s own piano at the<br />

Rachmaninov house in Lucerne. In October<br />

2008, at the personal invitation of Alexander<br />

Rachmaninov, Denis Matsuev was named<br />

Artistic Director of the Sergei Rachmaninov<br />

Foundation. As part of this partnership, he<br />

will perform in a series of gala concerts in<br />

some of the most prestigious concert halls<br />

throughout Europe and the United States.<br />

Denis Matsuev is Artistic Director of two<br />

Russian festivals: Stars on Baikal in Irkutsk,<br />

Siberia, and Crescendo, a series of events<br />

held in many different international cities<br />

including Moscow, St Petersburg, Tel-Aviv,<br />

Paris and New York. These remarkable<br />

festivals present a new generation of<br />

students from Russia’s music schools<br />

by featuring gifted Russian soloists from<br />

around the world performing with the best<br />

Russian orchestras. Additionally, Matsuev<br />

is the President of the charitable Russian<br />

foundation New Names.<br />

10 The Artists Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

Denis Matsuev © Andrey Mustafaev<br />

The Artists 11

On stage tonight<br />

First Violins<br />

Roman Simovic Leader<br />

Carmine Lauri<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Nicholas Wright<br />

Nigel Broadbent<br />

Ginette Decuyper<br />

Jörg Hammann<br />

Michael Humphrey<br />

Maxine Kwok-Adams<br />

Claire Parfitt<br />

Laurent Quenelle<br />

Colin Renwick<br />

Sylvain Vasseur<br />

Alain Petitclerc<br />

Hazel Mulligan<br />

Helen Paterson<br />

Second Violins<br />

David Alberman<br />

Thomas Norris<br />

Sarah Quinn<br />

Miya Ichinose<br />

Richard Blayden<br />

Belinda McFarlane<br />

Iwona Muszynska<br />

Philip Nolte<br />

Paul Robson<br />

Stephen Rowlinson<br />

David Worswick<br />

Caroline Frenkel<br />

Roisin Walters<br />

Oriana Kriszten<br />

Violas<br />

Paul Silverthorne<br />

Gillianne Haddow<br />

German Clavijo<br />

Lander Echevarria<br />

Richard Holttum<br />

Robert Turner<br />

Heather Wallington<br />

Jonathan Welch<br />

Martin Schaefer<br />

Michelle Bruil<br />

Caroline O’Neill<br />

Fiona Opie<br />

12 The <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Cellos<br />

Rebecca Gilliver<br />

Alastair Blayden<br />

Jennifer Brown<br />

Mary Bergin<br />

Noel Bradshaw<br />

Daniel Gardner<br />

Hilary Jones<br />

Minat Lyons<br />

Amanda Truelove<br />

Penny Driver<br />

Double Basses<br />

Rinat Ibragimov<br />

Colin Paris<br />

Nicholas Worters<br />

Patrick Laurence<br />

Matthew Gibson<br />

Thomas Goodman<br />

Jani Pensola<br />

Nikita Naumov<br />

Flutes<br />

Gareth Davies<br />

Adam Walker<br />

Siobhan Grealy<br />

Piccolo<br />

Sharon Williams<br />

Oboes<br />

Emanuel Abbühl<br />

Joseph Sanders<br />

Fraser MacAulay<br />

Cor Anglais<br />

Christine Pendrill<br />

Clarinets<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Chris Richards<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Bass Clarinet<br />

Lorenzo Iosco<br />

Bassoons<br />

Rachel Gough<br />

Bernardo Verde<br />

Joost Bosdijk<br />

Contra Bassoon<br />

Dominic Morgan<br />

Horns<br />

Timothy Jones<br />

David Pyatt<br />

Angela Barnes<br />

Estefanía Beceiro Vázquez<br />

Jonathan Lipton<br />

Trumpets<br />

Philip Cobb<br />

Nicholas Betts<br />

Gerald Ruddock<br />

Nigel Gomm<br />

Trombones<br />

Dudley Bright<br />

Katy Jones<br />

James Maynard<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Paul Milner<br />

Tuba<br />

Patrick Harrild<br />

Timpani<br />

Antoine Bedewi<br />

Percussion<br />

Neil Percy<br />

David Jackson<br />

Scott Bywater<br />

Helen Edordu<br />

Tom Edwards<br />

Sacha Johnson<br />

Harps<br />

Bryn Lewis<br />

Karen Vaughan<br />

Celeste/Piano<br />

John Alley<br />

LSO String<br />

Experience Scheme<br />

Established in 1992, the<br />

LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme enables young string<br />

players at the start of their<br />

professional careers to gain<br />

work experience by playing in<br />

rehearsals and concerts with<br />

the LSO. The scheme auditions<br />

students from the <strong>London</strong><br />

music conservatoires, and 20<br />

students per year are selected<br />

to participate. The musicians<br />

are treated as professional<br />

’extra’ players (additional to<br />

LSO members) and receive<br />

fees for their work in line with<br />

LSO section players. Students<br />

of wind, brass or percussion<br />

instruments who are in their<br />

final year or on a postgraduate<br />

course at one of the <strong>London</strong><br />

conservatoires can also<br />

benefit from training with LSO<br />

musicians in a similar scheme.<br />

The LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme is generously<br />

supported by the Musicians<br />

Benevolent Fund and Charles<br />

and Pascale Clark.<br />

Leslie Boulin Raulet (first violin),<br />

Yan Beattie (viola) and Damian<br />

Rubido González (double bass)<br />

are all playing in tonight’s<br />

concert as part of the LSO<br />

String Experience Scheme.<br />

List correct at time of<br />

going to press<br />

See page xv for <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> members<br />

Editor<br />

Edward Appleyard<br />

edward.appleyard@lso.co.uk<br />

Print<br />

Cantate 020 7622 3401<br />

Advertising<br />

Cabbell Ltd 020 8971 8450