25 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

25 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

25 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Rodion Shchedrin (b 1932)<br />

Piano Concerto No 5 (1999)<br />

Allegretto moderato<br />

Andante<br />

Allegro assai<br />

Denis Matsuev piano<br />

Since Prokofiev and Shostakovich, the number of front-rank<br />

composers who could also claim to be first-rate concert pianists has<br />

dwindled remarkably, and of the remaining few, hardly any have made<br />

piano music as strong a feature of their output as Rodion Shchedrin.<br />

Trained as a composer under Yuri Shaporin and as a pianist under<br />

Yakov Flier, he has composed six piano concertos to date, as well as a<br />

substantial body of solo piano works.<br />

In this area Shchedrin has generally shown more affinity for Prokofiev<br />

than for Shostakovich, especially the concertos, which at least initially<br />

were marked by vivid colours, forceful energy and total absence of<br />

self-doubt. His First Piano Concerto, for instance, a graduation piece<br />

from 1954, was a cheerfully extrovert romp that could have been<br />

designed as a tribute to Prokofiev, who had died the previous year.<br />

Twelve years later, the Second Concerto retained that influence,<br />

alongside a playful indulgence in twelve-note techniques.<br />

However, nearly 20 years separate the first three piano concertos,<br />

all of which Shchedrin premiered and recorded with himself as soloist,<br />

from the last three (No 3 was composed in 1973, No 4 in 1991).<br />

In this second phase, exhibitionism gives way to a more private,<br />

exploratory tone.<br />

The Fifth Piano Concerto was composed in 1999 for Finnish pianistcomposer<br />

Olli Mustonen, who gave the premiere in October that<br />

year with the Los Angeles Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong> under Esa-Pekka<br />

Salonen. Indeed the first movement seems initially designed to<br />

showcase Mustonen’s trademark pecking staccato touch, which is set<br />

off firstly against slow, singing lines, then against attractively scored<br />

scalic flourishes. The extended central section is slightly slower as<br />

well as weightier in tone, and it eventually inspires a more songful<br />

transformation of the opening material. This lengthy movement closes<br />

with a brief return of textures from the first section.<br />

4 Programme Notes<br />

The slow movement opens with an austere orchestral chorale, which<br />

the piano immediately takes up in a short cadenza. Ghosts of the first<br />

movement pass across the stage, but the main musical character<br />

seems to focus on four-note descending figures, highly malleable<br />

but almost always song-like.<br />

In essence a perpetuum mobile, the finale deliberately emulates<br />

the ‘crescendo with music’ of Ravel’s Bolero. For long stretches this<br />

movement demands greater virtuosity from the orchestra than the<br />

soloist, at least in terms of rhythmical precision. Finally the soloist cuts<br />

loose in a cadenza worthy of Shostakovich for its manic leaps, and<br />

when the orchestra rejoins it is with a Prokofievian style mécanique in<br />

overdrive, concluding the work with its most physically exciting pages.<br />

Shchedrin <strong>programme</strong> notes and profile © David Fanning<br />

David Fanning is a professor of music at the University of Manchester.<br />

He is an expert on Shostakovich, Nielsen and Soviet music. He is also<br />

a reviewer for the Daily Telegraph, Gramophone and BBC Radio 3.<br />

INTERVAL: 20 minutes<br />

I still today continue to be convinced that<br />

the decisive factor for each composition is<br />

intuition. As soon as composers relinquish<br />

their trust in this intuition and rely in its<br />

place on musical ‘religions’ such as serialism,<br />

aleatoric composition, minimalism or<br />

other methods, things become problematic.<br />

Rodion Shchedrin<br />

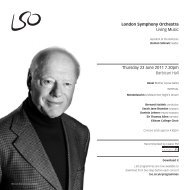

Rodion Shchedrin (b 1932)<br />

The Man<br />

The generation of Soviet composers after Shostakovich produced<br />

charismatic and exotic figures such as Galina Ustvolskaya,<br />

Alfred Schnittke and Sofiya Gubaydulina, whose music was initially<br />

controversial but then gained cult status. At the other end of the<br />

stylistic spectrum it featured highly gifted craftsmen such as<br />

Boris Tishchenko, Boris Tchaikovsky and Mieczysław Weinberg, all<br />

of whom worked more or less within the parameters laid down by<br />

Shostakovich and were highly respected in their heyday but gradually<br />

fell from favour.<br />

Somewhere in between we can locate Rodion Shchedrin – an<br />

individualist with a broader and more consistent appeal, who could<br />

turn himself chameleon-like to virtuoso pranks or to profound<br />

philosophical reflection, to Socialist Realist opera or to folkloristic<br />

Concertos for <strong>Orchestra</strong> (a particular speciality), to technically solid<br />

Preludes and Fugues, to jazz, and, when he chose, even to twelvenote<br />

constructivism.<br />

Trained at the Moscow Conservatoire in the 1950s, as a composer<br />

under Yuri Shaporin and as a pianist under Yakov Flier in the early<br />

years of the Post-Stalinist Thaw, Shchedrin was one of<br />

the first to speak out against the constraints of<br />

musical life in the Soviet Union. He went on to play<br />

a significant administrative role in the country’s<br />

musical life, heading the Russian Union of Composers<br />

from 1973 to 1990. Married since 1958 to the star<br />

Soviet ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, he established a<br />

significant power-base from which he was able to promote<br />

not only his own music but also that of others – such as<br />

Schnittke, whose notorious First <strong>Symphony</strong> received its<br />

sensational premiere only thanks to Shchedrin’s support.<br />

An unashamed eclectic, and suspicious of dogma from<br />

either the arch-modernist or arch-traditionalist wings of<br />

Soviet music, Shchedrin occupied a not always comfortable<br />

position, both in his pronouncements and in his creative<br />

work. With one foot in the national-traditional camp and the<br />

other in that of the internationalist-progressives, he was<br />

tagged with the unkind but not unfair label of the USSR’s<br />

Rodion Shchedrin © www.lebrecht.co.uk<br />

‘official modernist’. From 1992 he established a second home in<br />

Munich, but he still enjoyed official favour in post-Soviet Russia,<br />

adding steadily to his already impressive roster of prizes.<br />

Shchedrin has summed up his artistic credo as follows: ‘I continue to<br />

be convinced that the decisive factor for each composition is intuition.<br />

As soon as composers relinquish their trust in this intuition and rely in<br />

its place on musical ‘religions’ such as serialism, aleatoric composition,<br />

minimalism or other methods, things become problematic.’<br />

Programme Notes<br />

5