IPO Auctions: English, Dutch, ... French, and Internet

IPO Auctions: English, Dutch, ... French, and Internet

IPO Auctions: English, Dutch, ... French, and Internet

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

16 BIAIS AND FAUGERON-CROUZET<br />

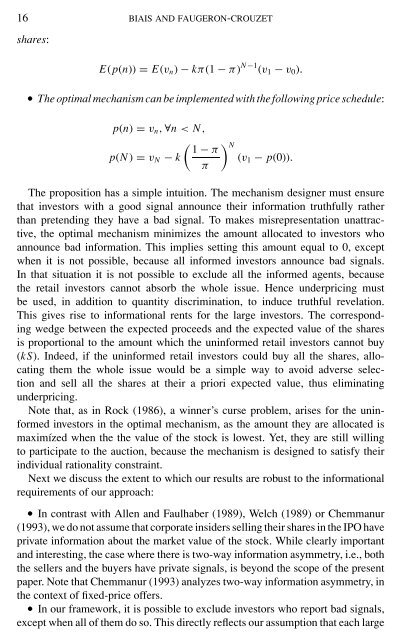

shares:<br />

E(p(n)) = E(vn) − kπ(1 − π) N−1 (v1 − v0).<br />

• The optimal mechanism can be implemented with the following price schedule:<br />

p(n) = vn, ∀n < N,<br />

<br />

1 − π<br />

p(N) = vN − k<br />

π<br />

N<br />

(v1 − p(0)).<br />

The proposition has a simple intuition. The mechanism designer must ensure<br />

that investors with a good signal announce their information truthfully rather<br />

than pretending they have a bad signal. To makes misrepresentation unattractive,<br />

the optimal mechanism minimizes the amount allocated to investors who<br />

announce bad information. This implies setting this amount equal to 0, except<br />

when it is not possible, because all informed investors announce bad signals.<br />

In that situation it is not possible to exclude all the informed agents, because<br />

the retail investors cannot absorb the whole issue. Hence underpricing must<br />

be used, in addition to quantity discrimination, to induce truthful revelation.<br />

This gives rise to informational rents for the large investors. The corresponding<br />

wedge between the expected proceeds <strong>and</strong> the expected value of the shares<br />

is proportional to the amount which the uninformed retail investors cannot buy<br />

(kS). Indeed, if the uninformed retail investors could buy all the shares, allocating<br />

them the whole issue would be a simple way to avoid adverse selection<br />

<strong>and</strong> sell all the shares at their a priori expected value, thus eliminating<br />

underpricing.<br />

Note that, as in Rock (1986), a winner’s curse problem, arises for the uninformed<br />

investors in the optimal mechanism, as the amount they are allocated is<br />

maximízed when the the value of the stock is lowest. Yet, they are still willing<br />

to participate to the auction, because the mechanism is designed to satisfy their<br />

individual rationality constraint.<br />

Next we discuss the extent to which our results are robust to the informational<br />

requirements of our approach:<br />

• In contrast with Allen <strong>and</strong> Faulhaber (1989), Welch (1989) or Chemmanur<br />

(1993), we do not assume that corporate insiders selling their shares in the <strong>IPO</strong> have<br />

private information about the market value of the stock. While clearly important<br />

<strong>and</strong> interesting, the case where there is two-way information asymmetry, i.e., both<br />

the sellers <strong>and</strong> the buyers have private signals, is beyond the scope of the present<br />

paper. Note that Chemmanur (1993) analyzes two-way information asymmetry, in<br />

the context of fixed-price offers.<br />

• In our framework, it is possible to exclude investors who report bad signals,<br />

except when all of them do so. This directly reflects our assumption that each large