Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Structural</strong> <strong>reforms</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>macro</strong>-<strong>economic</strong> <strong>policy</strong><br />

/ 30<br />

to increase <strong>and</strong> promote collective bargaining <strong>and</strong><br />

trade unions' involvement in providing all workers<br />

with sufficient access to training <strong>and</strong> lifelong<br />

learning.<br />

B. Supporting upward mobility <strong>and</strong> career<br />

transition for displaced workers<br />

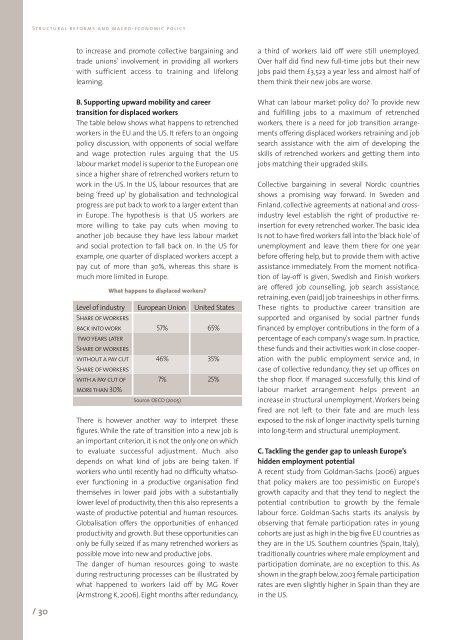

The table below shows what happens to retrenched<br />

workers in the EU <strong>and</strong> the US. It refers to an ongoing<br />

<strong>policy</strong> discussion, with opponents of social welfare<br />

<strong>and</strong> wage protection rules arguing that the US<br />

labour market model is superior to the European one<br />

since a higher share of retrenched workers return to<br />

work in the US. In the US, labour resources that are<br />

being ‘freed up’ by globalisation <strong>and</strong> technological<br />

progress are put back to work to a larger extent than<br />

in Europe. The hypothesis is that US workers are<br />

more willing to take pay cuts when moving to<br />

another job because they have less labour market<br />

<strong>and</strong> social protection to fall back on. In the US for<br />

example, one quarter of displaced workers accept a<br />

pay cut of more than 30%, whereas this share is<br />

much more limited in Europe.<br />

What happens to displaced workers?<br />

Level of industry European Union United States<br />

Share of workers<br />

back into work 57% 65%<br />

two years later<br />

Share of workers<br />

without a pay cut 46% 35%<br />

Share of workers<br />

with a pay cut of 7% 25%<br />

more than 30%<br />

Source: OECD (2005)<br />

There is however another way to interpret these<br />

figures. While the rate of transition into a new job is<br />

an important criterion, it is not the only one on which<br />

to evaluate successful adjustment. Much also<br />

depends on what kind of jobs are being taken. If<br />

workers who until recently had no difficulty whatsoever<br />

functioning in a productive organisation find<br />

themselves in lower paid jobs with a substantially<br />

lower level of productivity, then this also represents a<br />

waste of productive potential <strong>and</strong> human resources.<br />

Globalisation offers the opportunities of enhanced<br />

productivity <strong>and</strong> growth. But these opportunities can<br />

only be fully seized if as many retrenched workers as<br />

possible move into new <strong>and</strong> productive jobs.<br />

The danger of human resources going to waste<br />

during restructuring processes can be illustrated by<br />

what happened to workers laid off by MG Rover<br />

(Armstrong K, 2006). Eight months after redundancy,<br />

a third of workers laid off were still unemployed.<br />

Over half did find new full-time jobs but their new<br />

jobs paid them £3,523 a year less <strong>and</strong> almost half of<br />

them think their new jobs are worse.<br />

What can labour market <strong>policy</strong> do? To provide new<br />

<strong>and</strong> fulfilling jobs to a maximum of retrenched<br />

workers, there is a need for job transition arrangements<br />

offering displaced workers retraining <strong>and</strong> job<br />

search assistance with the aim of developing the<br />

skills of retrenched workers <strong>and</strong> getting them into<br />

jobs matching their upgraded skills.<br />

Collective bargaining in several Nordic countries<br />

shows a promising way forward. In Sweden <strong>and</strong><br />

Finl<strong>and</strong>, collective agreements at national <strong>and</strong> crossindustry<br />

level establish the right of productive reinsertion<br />

for every retrenched worker. The basic idea<br />

is not to have fired workers fall into the ‘black hole’ of<br />

unemployment <strong>and</strong> leave them there for one year<br />

before offering help, but to provide them with active<br />

assistance immediately. From the moment notification<br />

of lay-off is given, Swedish <strong>and</strong> Finish workers<br />

are offered job counselling, job search assistance,<br />

retraining, even (paid) job traineeships in other firms.<br />

These rights to productive career transition are<br />

supported <strong>and</strong> organised by social partner funds<br />

financed by employer contributions in the form of a<br />

percentage of each company's wage sum. In practice,<br />

these funds <strong>and</strong> their activities work in close cooperation<br />

with the public employment service <strong>and</strong>, in<br />

case of collective redundancy, they set up offices on<br />

the shop floor. If managed successfully, this kind of<br />

labour market arrangement helps prevent an<br />

increase in structural unemployment. Workers being<br />

fired are not left to their fate <strong>and</strong> are much less<br />

exposed to the risk of longer inactivity spells turning<br />

into long-term <strong>and</strong> structural unemployment.<br />

C. Tackling the gender gap to unleash Europe’s<br />

hidden employment potential<br />

A recent study from Goldman-Sachs (2006) argues<br />

that <strong>policy</strong> makers are too pessimistic on Europe's<br />

growth capacity <strong>and</strong> that they tend to neglect the<br />

potential contribution to growth by the female<br />

labour force. Goldman-Sachs starts its analysis by<br />

observing that female participation rates in young<br />

cohorts are just as high in the big five EU countries as<br />

they are in the US. Southern countries (Spain, Italy),<br />

traditionally countries where male employment <strong>and</strong><br />

participation dominate, are no exception to this. As<br />

shown in the graph below, 2003 female participation<br />

rates are even slightly higher in Spain than they are<br />

in the US.