Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Structural</strong> <strong>reforms</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>macro</strong>-<strong>economic</strong> <strong>policy</strong><br />

/ 82<br />

The internal dimension of wage-price flexibility stems<br />

from the fact that wages are not just costs, but also<br />

incomes. As a result of ‘wage moderation’, wageincome<br />

earners in Germany are confronted with<br />

moderate disposable income growth, which comes on<br />

top of general job market uncertainties <strong>and</strong> SGPimposed<br />

budget cuts.While there are few better ways<br />

to depress private consumption growth, as Figure 7<br />

shows, the opposite has been true in Spain, where on<br />

top of a booming job market, private consumption<br />

also found support from less moderate wage rises.<br />

The point is that private consumption tends to be the<br />

most important GDP component. Especially in larger<br />

economies, private consumption typically has much<br />

greater weight in GDP than exports. Even as the<br />

external dimension of wage-price flexibility may<br />

boost net exports <strong>and</strong> GDP, its internal dimension can<br />

provide an overwhelming drag on growth.<br />

How divergences are amplified<br />

by financial propagation mechanisms<br />

It is highly doubtful whether a large economy (such as<br />

the euro area) should run a growth strategy that relies<br />

on external competitiveness gains, especially in today’s<br />

environment of global imbalances. It is true, though,<br />

that wage moderation can also boost employment<br />

other than through external competitiveness gains,<br />

namely by forcing expansionary monetary <strong>policy</strong> upon<br />

the central bank. It is through its disinflationary effects<br />

that wage moderation provides an avenue to employment<br />

growth through domestic dem<strong>and</strong>, at least if the<br />

monetary <strong>policy</strong>-maker complies <strong>and</strong> boosts domestic<br />

dem<strong>and</strong> accordingly.<br />

In the case of the US, this channel is quasi-automatic.<br />

Let us recall that the US Fed has a clear double<br />

m<strong>and</strong>ate: maximum employment <strong>and</strong> price stability.<br />

As the economy slumps, the Fed is therefore bound to<br />

ease <strong>policy</strong>, so as to support employment. But even in<br />

the case of an inflation targeter like the Bank of<br />

Engl<strong>and</strong>, for instance, a growth slowdown elicits<br />

monetary easing, namely through its impact on wage<br />

dynamics <strong>and</strong> the inflation forecast.<br />

Although the ECB, too, is m<strong>and</strong>ated to support<br />

<strong>economic</strong> growth <strong>and</strong> employment, ‘without prejudice’<br />

to its primary goal of price stability, important<br />

complications arise here due to the ECB’s idiosyncratic<br />

interpretation of its role. One key problem is<br />

that, in the ECB’s view, price stability by itself is<br />

always the best contribution that monetary <strong>policy</strong><br />

can make to any other goal. Another key problem is<br />

that it is not so much forecast inflation but past<br />

inflation which seems to guide the ECB. The ECB’s<br />

rear-view mirror approach has had a vastly detrimental<br />

effect on <strong>economic</strong> performance: after<br />

choking growth through its aggressive interest rate<br />

hikes back in 2000, the ECB then failed to ease in<br />

time as the productivity slump (2001-02) <strong>and</strong> taxpush<br />

inflation (2002-05) kept inflation above its selfdeclared<br />

two per cent tolerance level (Bibow 2005b).<br />

While no one else but the ECB is responsible for<br />

these serious <strong>policy</strong> blunders, monetary <strong>policy</strong> is not<br />

to blame for the following complication, which is,<br />

however, intimately related to wage <strong>and</strong> inflation<br />

divergences within the euro area. Instead, individual<br />

member states have to be aware that the quasiautomatic<br />

route between wage moderation <strong>and</strong><br />

monetary easing is blocked in a currency union. In<br />

fact, wage moderation in any one member country<br />

relative to the average can even backfire. The point<br />

is that the disinflationary impact of national wage<br />

moderation on national price inflation only reduces<br />

euro area inflation by the respective country’s<br />

weight in the overall HICP. Thus, at best a partial<br />

reward from the ECB may be triggered in this way. If<br />

inflation increased elsewhere in the currency union<br />

at the same time, not even a partial reward would<br />

be forthcoming. This is because the monetary <strong>policy</strong><br />

domain <strong>and</strong> the domain of wage moderation are<br />

not the same – unlike the situation in Germany<br />

under Bundesbank rule. Making things worse still,<br />

today, as German inflation declines relative to inflation<br />

elsewhere in the euro area, German real<br />

interest rates rise both absolutely <strong>and</strong> relative to the<br />

euro area average.<br />

But this is not where the story ends. Diverging real<br />

interest rates – driven by wage-price flexibility <strong>and</strong><br />

inflation divergences – will be likely to trigger important<br />

propagation mechanisms in the financial<br />

system. In particular, while negative real interest<br />

rates are likely to ignite a lending boom in Spain, with<br />

rising asset prices <strong>and</strong> improving creditworthiness of<br />

borrowers leading to more credit ease, quite the<br />

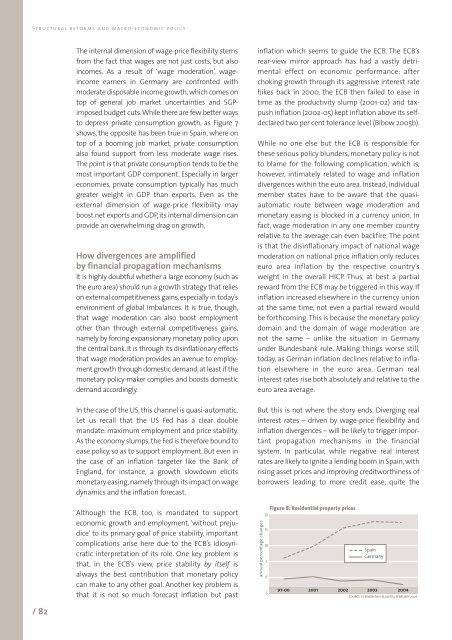

annual percentage changes<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

-5<br />

Figure 8: Residential property prices<br />

97-00 2001 2002<br />

Spain<br />

Germany<br />

2003 2004<br />

SOURCE: ECB MONTHLY BULLETIN, FEBRUARY 2006