Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

Structural reforms and macro-economic policy - ETUC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Structural</strong> <strong>reforms</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>macro</strong>-<strong>economic</strong> <strong>policy</strong><br />

/ 84<br />

The above analysis has shown how the Maastricht<br />

regime in conjunction with the working of market<br />

forces in line with wage-price flexibility has suffocated<br />

domestic dem<strong>and</strong> in Germany. While this<br />

explains the German domestic dem<strong>and</strong> malaise, it is<br />

not where the problem ends for the euro area as a<br />

whole. The point is that through relative wage disinflation<br />

<strong>and</strong> for no good reason, Germany has achieved<br />

a sizeable real devaluation at the expense of its<br />

European partners. Essentially, Germany has pursued<br />

a beggar-thy-neighbour strategy. Reflecting the inappropriateness<br />

of Germany’s reliance on the competitiveness<br />

channel, intra-euro area current account<br />

imbalances are mounting as a consequence (see<br />

Figure 3 above). Rather than restoring individual<br />

members’ external balance while helping to achieve<br />

internal balance in the union as a whole, growth in<br />

the euro area has become seriously unbalanced <strong>and</strong><br />

competitiveness trends have diverged as the<br />

supposed partners are drifting apart.<br />

Source OCDE Economic Outlook no. 78 (Dec 20)<br />

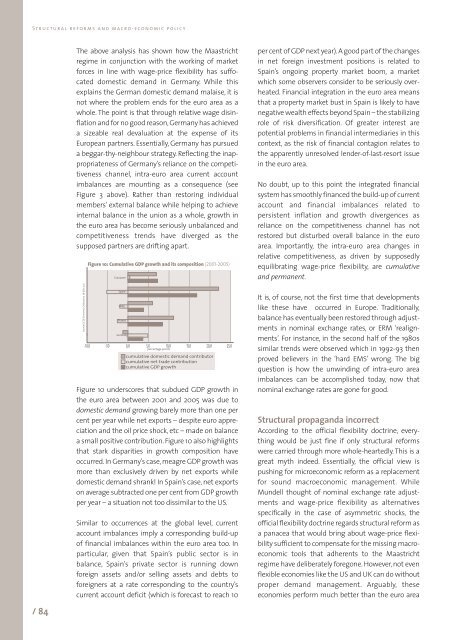

Figure 10: Cumulative GDP growth <strong>and</strong> its composition (2001-2005)<br />

Eurozone<br />

Spain<br />

Italy<br />

France<br />

Germany<br />

-10,0 -50 0,0 5,0 10,0 15,0 20,0 25,0<br />

percentage points<br />

cumulative domestic dem<strong>and</strong> contributor<br />

cumulative net trade contribution<br />

cumulative GDP growth<br />

Figure 10 underscores that subdued GDP growth in<br />

the euro area between 2001 <strong>and</strong> 2005 was due to<br />

domestic dem<strong>and</strong> growing barely more than one per<br />

cent per year while net exports – despite euro appreciation<br />

<strong>and</strong> the oil price shock, etc – made on balance<br />

a small positive contribution. Figure 10 also highlights<br />

that stark disparities in growth composition have<br />

occurred. In Germany’s case, meagre GDP growth was<br />

more than exclusively driven by net exports while<br />

domestic dem<strong>and</strong> shrank! In Spain’s case, net exports<br />

on average subtracted one per cent from GDP growth<br />

per year – a situation not too dissimilar to the US.<br />

Similar to occurrences at the global level, current<br />

account imbalances imply a corresponding build-up<br />

of financial imbalances within the euro area too. In<br />

particular, given that Spain’s public sector is in<br />

balance, Spain’s private sector is running down<br />

foreign assets <strong>and</strong>/or selling assets <strong>and</strong> debts to<br />

foreigners at a rate corresponding to the country’s<br />

current account deficit (which is forecast to reach 10<br />

per cent of GDP next year). A good part of the changes<br />

in net foreign investment positions is related to<br />

Spain’s ongoing property market boom, a market<br />

which some observers consider to be seriously overheated.<br />

Financial integration in the euro area means<br />

that a property market bust in Spain is likely to have<br />

negative wealth effects beyond Spain – the stabilizing<br />

role of risk diversification. Of greater interest are<br />

potential problems in financial intermediaries in this<br />

context, as the risk of financial contagion relates to<br />

the apparently unresolved lender-of-last-resort issue<br />

in the euro area.<br />

No doubt, up to this point the integrated financial<br />

system has smoothly financed the build-up of current<br />

account <strong>and</strong> financial imbalances related to<br />

persistent inflation <strong>and</strong> growth divergences as<br />

reliance on the competitiveness channel has not<br />

restored but disturbed overall balance in the euro<br />

area. Importantly, the intra-euro area changes in<br />

relative competitiveness, as driven by supposedly<br />

equilibrating wage-price flexibility, are cumulative<br />

<strong>and</strong> permanent.<br />

It is, of course, not the first time that developments<br />

like these have occurred in Europe. Traditionally,<br />

balance has eventually been restored through adjustments<br />

in nominal exchange rates, or ERM ‘realignments’.<br />

For instance, in the second half of the 1980s<br />

similar trends were observed which in 1992-93 then<br />

proved believers in the ‘hard EMS’ wrong. The big<br />

question is how the unwinding of intra-euro area<br />

imbalances can be accomplished today, now that<br />

nominal exchange rates are gone for good.<br />

<strong>Structural</strong> propag<strong>and</strong>a incorrect<br />

According to the official flexibility doctrine, everything<br />

would be just fine if only structural <strong>reforms</strong><br />

were carried through more whole-heartedly. This is a<br />

great myth indeed. Essentially, the official view is<br />

pushing for micro<strong>economic</strong> reform as a replacement<br />

for sound <strong>macro</strong><strong>economic</strong> management. While<br />

Mundell thought of nominal exchange rate adjustments<br />

<strong>and</strong> wage-price flexibility as alternatives<br />

specifically in the case of asymmetric shocks, the<br />

official flexibility doctrine regards structural reform as<br />

a panacea that would bring about wage-price flexibility<br />

sufficient to compensate for the missing <strong>macro</strong><strong>economic</strong><br />

tools that adherents to the Maastricht<br />

regime have deliberately foregone. However, not even<br />

flexible economies like the US <strong>and</strong> UK can do without<br />

proper dem<strong>and</strong> management. Arguably, these<br />

economies perform much better than the euro area