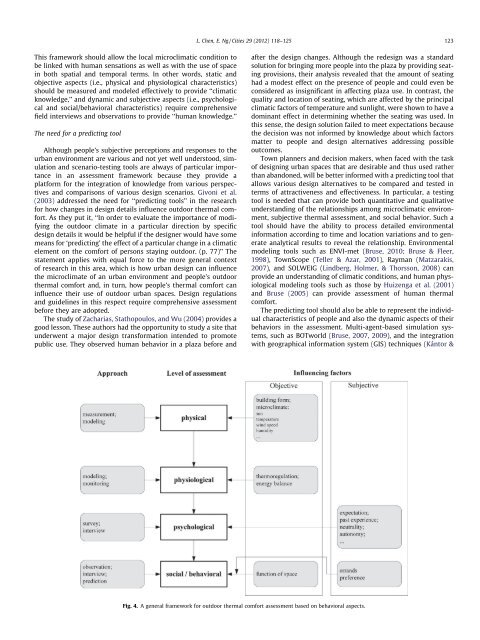

This framework should allow the local microclimatic condition to be linked with human sensations as well as with the use <strong>of</strong> space in both spatial <strong>and</strong> temporal terms. In other words, static <strong>and</strong> objective aspects (i.e., physical <strong>and</strong> physiological characteristics) should be measured <strong>and</strong> modeled effectively to provide ‘‘climatic knowledge,’’ <strong>and</strong> dynamic <strong>and</strong> subjective aspects (i.e., psychological <strong>and</strong> social/behavioral characteristics) require comprehensive field interviews <strong>and</strong> observations to provide ‘‘human knowledge.’’ The need for a predicting tool Although people’s subjective perceptions <strong>and</strong> responses to the urban environment are various <strong>and</strong> not yet well understood, simulation <strong>and</strong> scenario-testing tools are always <strong>of</strong> particular importance in an assessment framework because they provide a platform for the integration <strong>of</strong> knowledge from various perspectives <strong>and</strong> comparisons <strong>of</strong> various design scenarios. Givoni et al. (2003) addressed the need for ‘‘predicting tools’’ in the <strong>research</strong> for how changes in design details influence <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong>. As they put it, ‘‘In order to evaluate the importance <strong>of</strong> modifying the <strong>outdoor</strong> climate in a particular direction by specific design details it would be helpful if the designer would have some means for ‘predicting’ the effect <strong>of</strong> a particular change in a climatic element on the <strong>comfort</strong> <strong>of</strong> persons staying <strong>outdoor</strong>. (p. 77)’’ The statement applies with equal force to the more general context <strong>of</strong> <strong>research</strong> in this area, which is how urban design can influence the microclimate <strong>of</strong> an urban environment <strong>and</strong> people’s <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> <strong>and</strong>, in turn, how people’s <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> can influence their use <strong>of</strong> <strong>outdoor</strong> urban spaces. Design regulations <strong>and</strong> guidelines in this respect require comprehensive assessment before they are adopted. The study <strong>of</strong> Zacharias, Stathopoulos, <strong>and</strong> Wu (2004) provides a good lesson. These authors had the opportunity to study a site that underwent a major design transformation intended to promote public use. They observed human behavior in a plaza before <strong>and</strong> L. Chen, E. Ng / Cities 29 (2012) 118–125 123 after the design changes. Although the redesign was a st<strong>and</strong>ard solution for bringing more people into the plaza by providing seating provisions, their analysis revealed that the amount <strong>of</strong> seating had a modest effect on the presence <strong>of</strong> people <strong>and</strong> could even be considered as insignificant in affecting plaza use. In contrast, the quality <strong>and</strong> location <strong>of</strong> seating, which are affected by the principal climatic factors <strong>of</strong> temperature <strong>and</strong> sunlight, were shown to have a dominant effect in determining whether the seating was used. In this sense, the design solution failed to meet expectations because the decision was not informed by knowledge about which factors matter to people <strong>and</strong> design alternatives addressing possible outcomes. Town planners <strong>and</strong> decision makers, when faced with the task <strong>of</strong> designing urban spaces that are desirable <strong>and</strong> thus used rather than ab<strong>and</strong>oned, will be better informed with a predicting tool that allows various design alternatives to be compared <strong>and</strong> tested in terms <strong>of</strong> attractiveness <strong>and</strong> effectiveness. In particular, a testing tool is needed that can provide both quantitative <strong>and</strong> qualitative underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> the relationships among microclimatic environment, subjective <strong>thermal</strong> assessment, <strong>and</strong> social behavior. Such a tool should have the ability to process detailed environmental information according to time <strong>and</strong> location variations <strong>and</strong> to generate analytical results to reveal the relationship. Environmental modeling tools such as ENVI-met (Bruse, 2010; Bruse & Fleer, 1998), TownScope (Teller & Azar, 2001), Rayman (Matzarakis, 2007), <strong>and</strong> SOLWEIG (Lindberg, Holmer, & Thorsson, 2008) can provide an underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> climatic conditions, <strong>and</strong> human physiological modeling tools such as those by Huizenga et al. (2001) <strong>and</strong> Bruse (2005) can provide assessment <strong>of</strong> human <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong>. The predicting tool should also be able to represent the individual characteristics <strong>of</strong> people <strong>and</strong> also the dynamic aspects <strong>of</strong> their behaviors in the assessment. Multi-agent-based simulation systems, such as BOTworld (Bruse, 2007, 2009), <strong>and</strong> the integration with geographical information system (GIS) techniques (Kántor & Fig. 4. A general framework for <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> assessment based on behavioral aspects.

124 L. Chen, E. Ng / Cities 29 (2012) 118–125 Unger, 2010) are expected to provide new approaches to underst<strong>and</strong>ing the influences <strong>of</strong> the <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> environment on human activity <strong>and</strong> people’s use <strong>of</strong> <strong>outdoor</strong> space <strong>and</strong> the planning implications. Acknowledgments The <strong>research</strong> is supported by a PGS studentship from The Chinese University <strong>of</strong> Hong Kong. Special thanks are given to the <strong>review</strong>ers <strong>and</strong> the editors for their valuable comments <strong>and</strong> thorough editing efforts. Their contribution has indeed improved the work a lot. Thanks also go to Pr<strong>of</strong>. Höppe <strong>and</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>. Nikolopoulou for generously permitting the use <strong>of</strong> their figures. References Ahmed, K. S. (2003). Comfort in urban spaces: Defining the boundaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> for the tropical urban environments. Energy <strong>and</strong> Buildings, 35, 103–110. Ali-Toudert, F., & Mayer, H. (2006). Numerical study on the effects <strong>of</strong> aspect ratio <strong>and</strong> orientation <strong>of</strong> an urban street canyon on <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> in hot <strong>and</strong> dry climate. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 41, 94–108. Bosselmann, P., Dake, K., Fountain, M., Kraus, L., Lin, K. T., & Harris, A. (1988). Sun, wind <strong>and</strong> <strong>comfort</strong>: A field study <strong>of</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> in San Francisco. Centre for Environmental Design Research, University <strong>of</strong> California Berkeley. Bruse, M. (2005). ITCM – A simple dynamic 2-node model <strong>of</strong> the human thermoregulatory system <strong>and</strong> its application in a multi-agent system. Annual Meteorology, 41, 398–401. Bruse, M. (2007). BOTworld homepage. Retrieved 04.11.10. Bruse, M. (2009, 29 June–3 July). Analyzing human <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> <strong>and</strong> open space usage with the multi-agent system BOTworld. In Paper presented at the 7th international conference on urban climate (ICUC-7), Yokohama, Japan. Bruse, M. (2010) ENVI-met homepage. Retrieved 04.11.10. Bruse, M., & Fleer, H. (1998). Simulating surface–plant–air interactions inside urban environments with a three-dimensional numerical model. Environmental Modelling <strong>and</strong> S<strong>of</strong>tware, 3, 373–384. Carr, S., Francis, M., Rivlin, L. G., & Stone, A. M. (1993). Public space. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. Cheng, V., & Ng, E. (2006). Thermal <strong>comfort</strong> in urban open spaces for Hong Kong. Architectural Science Review, 49(3), 236–242. Cheng, V., Ng, E., Chan, C., & Givoni, B. (2010). <strong>Outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> study in sub-tropical climate: A longitudinal study based in Hong Kong. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology. doi:10.1007/s00484-010-0396-z. City <strong>and</strong> County <strong>of</strong> San Francisco (1985). Downtown: An area plan <strong>of</strong> the master plan <strong>of</strong> the City <strong>and</strong> County <strong>of</strong> San Francisco. San Francisco: City <strong>of</strong> San Francisco. Eliasson, I., Knez, I., Westerberg, U., Thorsson, S., & Lindberg, F. (2007). Climate <strong>and</strong> behaviour in a Nordic city. L<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> Urban Planning, 82, 72–84. Fanger, P. O. (1982). Thermal <strong>comfort</strong>. Analysis <strong>and</strong> application in environment engineering. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company. Fiala, D., Lomas, K. J., & Stohrer, M. (2001). Computer prediction <strong>of</strong> human thermoregulatory <strong>and</strong> temperature responses to a wide range <strong>of</strong> environmental conditions. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology, 45, 143–159. Foda, E., & Sirén, K. (2010). A new approach using the Pierce two-node model for different body parts. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology. doi:10.1007/ s00484-010-0375-4. Gagge, A. P., Fobelets, A. P., & Berglund, L. G. (1986). A st<strong>and</strong>ard predictive index <strong>of</strong> human response to the <strong>thermal</strong> environment. ASHRAE Transactions, 92(2B), 709–731. Gagge, A. P., Stolwijk, J. A. J., & Nishi, Y. (1971). An effective temperature scale based on a simple model <strong>of</strong> human physiological regulatory response. ASHRAE Transactions, 77(1), 247–262. Gehl, J. (1971). Life between buildings: Using public space. Danish Architecture Press, Distributed by Isl<strong>and</strong> Press. Gehl, J., & Gemzøe, L. (2004). Public spaces, public life, Copenhagen. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press <strong>and</strong> the Royal Danish Academy <strong>of</strong> Fine Arts, School <strong>of</strong> Architecture Publishers. Givoni, B. (1976). Man, climate <strong>and</strong> architecture. London: Applied Science Publishers. Givoni, B., Noguchi, M., Saaroni, H., Pochter, O., Yaacov, Y., Feller, N., et al. (2003). <strong>Outdoor</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> <strong>research</strong> issues. Energy <strong>and</strong> Buildings, 35(1), 77–86. Gulyas, A., Unger, J., & Matzarakis, A. (2006). Assessment <strong>of</strong> the microclimatic <strong>and</strong> human <strong>comfort</strong> conditions in a complex urban environment: Modelling <strong>and</strong> measurements. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 41, 1713–1722. Hakim, A. A., Petrovitch, H., Burchfiel, C. M., Ross, G. W., Rodriguez, B. L., White, L. R., et al. (1998). Effects <strong>of</strong> walking on mortality among nonsmoking retired men. New Engl<strong>and</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Medicine, 338, 94–99. Hamdi, M., Lachiver, G., & Michaud, F. (1999). A new predictive <strong>thermal</strong> sensation index <strong>of</strong> human response. Energy <strong>and</strong> Buildings, 29, 167–178. Hass-Klau, C. (1993). Impact <strong>of</strong> pedestrianisation <strong>and</strong> traffic calming on retailing: A <strong>review</strong> <strong>of</strong> the evidence from Germany. Transport Policy, 1(1), 21–31. Havenith, G. (2001). Individualized model <strong>of</strong> human thermoregulation for the simulation <strong>of</strong> heat stress response. Journal <strong>of</strong> Applied Physiology, 90(5), 1943–1954. Höppe, P. (1984). Die Energiebilanz des Menschen (English translation: The energy balance in human). Wiss Mitt Meteorol Inst Univ Mtinchen 49. Höppe, P. (1999). The physiological equivalent temperature – A universal index for the biometeorological assessment <strong>of</strong> the <strong>thermal</strong> environment. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology, 43, 71–75. Höppe, P. (2002). Different aspects <strong>of</strong> assessing indoor <strong>and</strong> <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong>. Energy <strong>and</strong> Buildings, 34, 661–665. Huizenga, C., Zhang, H., & Arens, E. (2001). A model <strong>of</strong> human physiology <strong>and</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> for assessing complex <strong>thermal</strong> environments. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 36(2001), 691–699. ISO (1994). Moderate <strong>thermal</strong> environments – Determination <strong>of</strong> the PMV <strong>and</strong> PPD indices <strong>and</strong> the specification <strong>of</strong> conditions for <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong>. Geneva: International St<strong>and</strong>ard 7730. Jacobs, J. (1972). The death <strong>and</strong> life <strong>of</strong> great American cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin. Jendritzky, G., Maarouf, A., & Staiger, H. (2001). Looking for a universal <strong>thermal</strong> climate index: UTCI for <strong>outdoor</strong> applications. In Paper presented at the Windsorconference on <strong>thermal</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards, Windsor, UK. Kántor, N., & Unger, J. (2010). Benefits <strong>and</strong> opportunities <strong>of</strong> adopting GIS in <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> studies in resting places: An urban park as an example. L<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> Urban Planning, 98(1), 36–46. Katzschner, L. (2006). Behaviour <strong>of</strong> people in open spaces in dependence <strong>of</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> conditions. In Paper presented at the PLEA2006 – The 23rd conference on passive <strong>and</strong> low energy architecture, Geneva, Switzerl<strong>and</strong>. Kenny, N. A., Warl<strong>and</strong>, J. S., Brown, R. D., & Gillespie, T. G. (2009). Part A: Assessing the performance <strong>of</strong> the COMFA <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> model on subjects performing physical activity. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology, 53, 415–428. Knez, I., & Thorsson, S. (2006). Influences <strong>of</strong> culture <strong>and</strong> environmental attitude on <strong>thermal</strong>, emotional <strong>and</strong> perceptual evaluations <strong>of</strong> a public square. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology, 50, 258–268. doi:10.1007/s00484-006-0024-0. Li, S. (1994). User’s behaviour <strong>of</strong> small urban spaces in winter <strong>and</strong> marginal seasons. Architecture <strong>and</strong> Behaviour, 10, 95–109. Lin, T.-P. (2009). Thermal perception, adaptation <strong>and</strong> attendance in a public square in hot <strong>and</strong> humid regions. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 44, 2017–2026. Lindberg, F., Holmer, B., & Thorsson, S. (2008). SOLWEIG 1.0 – Modelling spatial variations <strong>of</strong> 3D radiant fluxes <strong>and</strong> mean radiant temperature in complex urban settings. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology, 52(7), 697–713. Marcus, C. C., & Francis, C. (1998). People places – Design guidelines for urban open space. New York: Wiley & Sons, Inc. Maruani, T., & Amit-Cohen, I. (2007). Open space planning models: A <strong>review</strong> <strong>of</strong> approaches <strong>and</strong> methods. L<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> Urban Planning, 81(1–2), 1–13. Matzarakis, A. (2007). Modelling radiation fluxes in simple <strong>and</strong> complex environments—Application <strong>of</strong> the RayMan model. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology, 51(4), 323–334. Matzarakis, A., Mayer, H., & Iziomon, M. G. (1999). Applications <strong>of</strong> a universal <strong>thermal</strong> index: Physiological equivalent temperature. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biometeorology, 43, 76–84. Mayer, H., & Höppe, P. (1987). Thermal <strong>comfort</strong> <strong>of</strong> man in different urban environments. Theoretical <strong>and</strong> Applied Climatology, 38, 43–49. Nagano, K., & Horikoshi, T. (2011). New index indicating the universal <strong>and</strong> separate effects on human <strong>comfort</strong> under <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>and</strong> non-uniform <strong>thermal</strong> conditions. Energy <strong>and</strong> Buildings, 43(7), 1694–1701. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.03.012. Nagara, K., Shimoda, Y., & Mizuno, M. (1996). Evaluation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>thermal</strong> environment in an <strong>outdoor</strong> pedestrian space. Atmospheric Environment, 30(3), 497–505. Nikolopoulou, M., Baker, N., & Steemers, K. (2001). Thermal <strong>comfort</strong> in <strong>outdoor</strong> urban spaces: Underst<strong>and</strong>ing the human parameter. Solar Energy, 70, 227–235. Nikolopoulou, M., & Lykoudis, S. (2006). Thermal <strong>comfort</strong> in <strong>outdoor</strong> urban spaces: Analysis across different European countries. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 41(11), 1455–1470. Nikolopoulou, M., & Lykoudis, S. (2007). Use <strong>of</strong> <strong>outdoor</strong> spaces <strong>and</strong> microclimate in a Mediterranean urban area. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 42(10), 3691–3707. Nikolopoulou, M., & Steemers, K. (2003). Thermal <strong>comfort</strong> <strong>and</strong> psychological adaptation as a guide for designing urban spaces. Energy <strong>and</strong> Buildings, 35(1), 95–101. Pickup, J., & De Dear, R. (1999, 8–12, November). An <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> index (OUT_SET ) – Part 1: The model <strong>and</strong> its assumptions. In Paper presented at the 15th international congress <strong>of</strong> biometeorology <strong>and</strong> international conference <strong>of</strong> urban climatology, Sydney, Australia. Population Reference Bureau (2009). 2009 World population data sheet. Retrieved23.09.10. Shimazaki, Y., Yoshida, A., Suzuki, R., Kawabata, T., Imai, D., & Kinoshita, S. (2011). Application <strong>of</strong> human <strong>thermal</strong> load into unsteady condition for improvement <strong>of</strong> <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong>. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 46(8), 1716–1724. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2011.02.013. Spagnolo, J., & De Dear, R. (2003). A field study <strong>of</strong> <strong>thermal</strong> <strong>comfort</strong> in <strong>outdoor</strong> <strong>and</strong> semi-<strong>outdoor</strong> environments in subtropical Sydney Australia. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 38(5), 721–738. Stathopoulos, T., Wu, H., & Zacharias, J. (2004). <strong>Outdoor</strong> human <strong>comfort</strong> in an urban climate. Building <strong>and</strong> Environment, 39(3), 297–305. Task Committee on <strong>Outdoor</strong> Human Comfort <strong>of</strong> the Aerodynamics, Committee <strong>of</strong> the American Society <strong>of</strong> Civil Engineers (2004). <strong>Outdoor</strong> human <strong>comfort</strong> <strong>and</strong> its assessment: State <strong>of</strong> the art. Reston, VA: American Society <strong>of</strong> Civil Engineers.