2006-2007 Fall/Winter Directions - Friends' Central School

2006-2007 Fall/Winter Directions - Friends' Central School

2006-2007 Fall/Winter Directions - Friends' Central School

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

FEATURES – ALUMNI/AE<br />

Sidney Bridges’79<br />

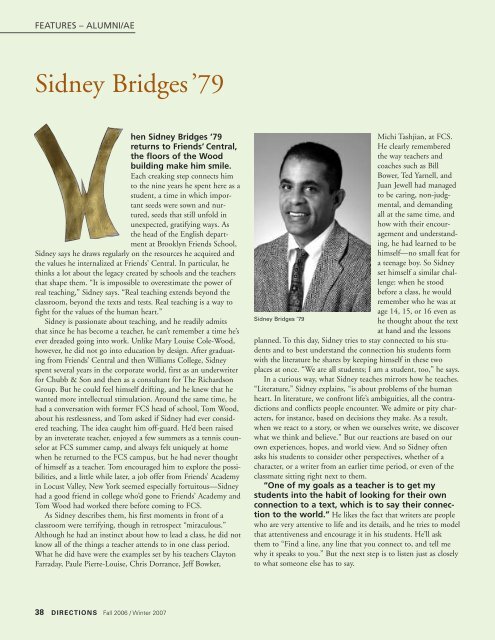

hen Sidney Bridges ’79<br />

returns to Friends’ <strong>Central</strong>,<br />

the floors of the Wood<br />

building make him smile.<br />

Each creaking step connects him<br />

to the nine years he spent here as a<br />

student, a time in which important<br />

seeds were sown and nurtured,<br />

seeds that still unfold in<br />

unexpected, gratifying ways. As<br />

the head of the English department<br />

at Brooklyn Friends <strong>School</strong>,<br />

Sidney says he draws regularly on the resources he acquired and<br />

the values he internalized at Friends’ <strong>Central</strong>. In particular, he<br />

thinks a lot about the legacy created by schools and the teachers<br />

that shape them. “It is impossible to overestimate the power of<br />

real teaching,” Sidney says. “Real teaching extends beyond the<br />

classroom, beyond the texts and tests. Real teaching is a way to<br />

fight for the values of the human heart.”<br />

Sidney is passionate about teaching, and he readily admits<br />

that since he has become a teacher, he can’t remember a time he’s<br />

ever dreaded going into work. Unlike Mary Louise Cole-Wood,<br />

however, he did not go into education by design. After graduating<br />

from Friends’ <strong>Central</strong> and then Williams College, Sidney<br />

spent several years in the corporate world, first as an underwriter<br />

for Chubb & Son and then as a consultant for The Richardson<br />

Group. But he could feel himself drifting, and he knew that he<br />

wanted more intellectual stimulation. Around the same time, he<br />

had a conversation with former FCS head of school, Tom Wood,<br />

about his restlessness, and Tom asked if Sidney had ever considered<br />

teaching. The idea caught him off-guard. He’d been raised<br />

by an inveterate teacher, enjoyed a few summers as a tennis counselor<br />

at FCS summer camp, and always felt uniquely at home<br />

when he returned to the FCS campus, but he had never thought<br />

of himself as a teacher. Tom encouraged him to explore the possibilities,<br />

and a little while later, a job offer from Friends’ Academy<br />

in Locust Valley, New York seemed especially fortuitous—Sidney<br />

had a good friend in college who’d gone to Friends’ Academy and<br />

Tom Wood had worked there before coming to FCS.<br />

As Sidney describes them, his first moments in front of a<br />

classroom were terrifying, though in retrospect “miraculous.”<br />

Although he had an instinct about how to lead a class, he did not<br />

know all of the things a teacher attends to in one class period.<br />

What he did have were the examples set by his teachers Clayton<br />

Farraday, Paule Pierre-Louise, Chris Dorrance, Jeff Bowker,<br />

38 DIRECTIONS <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2006</strong> / <strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2007</strong><br />

Michi Tashjian, at FCS.<br />

He clearly remembered<br />

the way teachers and<br />

coaches such as Bill<br />

Bower, Ted Yarnell, and<br />

Juan Jewell had managed<br />

to be caring, non-judgmental,<br />

and demanding<br />

all at the same time, and<br />

how with their encouragement<br />

and understanding,<br />

he had learned to be<br />

himself—no small feat for<br />

a teenage boy. So Sidney<br />

set himself a similar challenge:<br />

when he stood<br />

before a class, he would<br />

remember who he was at<br />

age 14, 15, or 16 even as<br />

Sidney Bridges ’79<br />

he thought about the text<br />

at hand and the lessons<br />

planned. To this day, Sidney tries to stay connected to his students<br />

and to best understand the connection his students form<br />

with the literature he shares by keeping himself in these two<br />

places at once. “We are all students; I am a student, too,” he says.<br />

In a curious way, what Sidney teaches mirrors how he teaches.<br />

“Literature,” Sidney explains, “is about problems of the human<br />

heart. In literature, we confront life’s ambiguities, all the contradictions<br />

and conflicts people encounter. We admire or pity characters,<br />

for instance, based on decisions they make. As a result,<br />

when we react to a story, or when we ourselves write, we discover<br />

what we think and believe.” But our reactions are based on our<br />

own experiences, hopes, and world view. And so Sidney often<br />

asks his students to consider other perspectives, whether of a<br />

character, or a writer from an earlier time period, or even of the<br />

classmate sitting right next to them.<br />

“One of my goals as a teacher is to get my<br />

students into the habit of looking for their own<br />

connection to a text, which is to say their connection<br />

to the world.” He likes the fact that writers are people<br />

who are very attentive to life and its details, and he tries to model<br />

that attentiveness and encourage it in his students. He’ll ask<br />

them to “Find a line, any line that you connect to, and tell me<br />

why it speaks to you.” But the next step is to listen just as closely<br />

to what someone else has to say.