Download Visitor's guide PDF - Fondation Beyeler

Download Visitor's guide PDF - Fondation Beyeler

Download Visitor's guide PDF - Fondation Beyeler

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

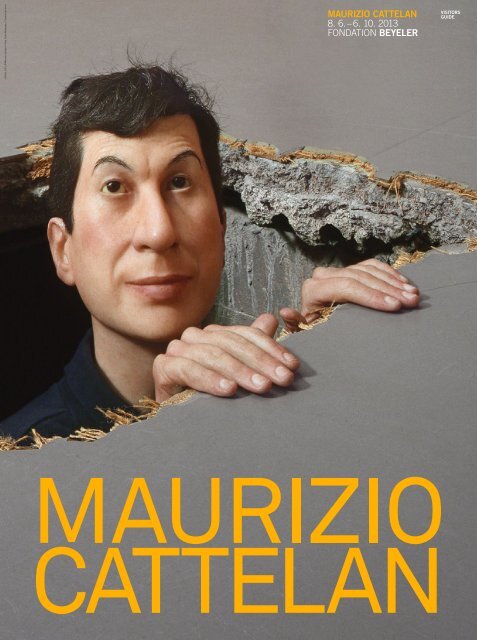

Untitled, 2001, © Maurizio Cattelan, Photo: Attilio Maranzano, Courtesy the artist<br />

Maurizio CaTTELaN<br />

8. 6. – 6. 10. 2013<br />

FONDATION BEYELEr<br />

VisiTors<br />

GuidE

Francesco Bonami<br />

Maurizio CaTTELaN<br />

KapuTT priMaVEra<br />

(1)<br />

SuRVIVAL INSTINCT<br />

“‘Did it ever occur to you,’ I said, ‘that the Swedish landscape is equine<br />

in character?’ Prince Eugene smiled and asked, ‘Do you know Carl Hill’s<br />

drawings of horses, Carl Hill’s hästar?’ And he added, ‘Carl Hill was mad;<br />

he thought trees were green horses.’ ‘Carl Hill,’ I replied, ‘painted horses<br />

as if they were landscapes…’”<br />

I came across this dialogue in Kaputt, a novel written by Curzio Malaparte.<br />

The characters engaged in this conversation are the author himself<br />

and Prince Eugene of Sweden. The first part of the novel is titled “The<br />

Horses” and it alone would be enough to gain an understanding of Maurizio<br />

Cattelan’s horses. In it, Malaparte writes about horses in a magical<br />

way, bringing to mind over and over again all the horses used by Cattelan<br />

in his work. In particular, the rotten mare in a pool of mud recalls Untitled<br />

(2009), Cattelan’s horse with a swollen belly pierced by a pole bearing a<br />

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2007, Photo: Axel Schneider, Courtesy Maurizio Cattelan’s Archive<br />

sign with the inscription „INRI.“ Or the horses trapped in the frozen waters<br />

of Lake Ladoga in Finland during World War II, with only their heads<br />

sticking out, their eyes frozen in terror. Malaparte tells of the frozen heads<br />

being used by soldiers as benches on which to smoke their cigarettes<br />

and pipes. And of the horrible stench of the rotten corpses when spring<br />

arrived, the ice melted and the bloated, dead horses started to float on<br />

the surface of the lake. It sounds gruesome and horrendous but actually<br />

Malaparte’s writing is very much like Cattelan’s visual language, located<br />

somewhere between the magical and the poetic, the tough and the lyrical.<br />

Prince Eugene, again, seems to describe it simply but perfectly: “La<br />

guerre même n’est qu’un rêve.” War itself is nothing but a dream. The<br />

work of Maurizio Cattelan is nothing but a dream—a disturbing dream,<br />

perhaps, but nevertheless a dream.<br />

The title of this text is Kaputt Primavera. It refers both to Malaparte’s<br />

novel and to his description of spring on the shores of the Finnish lake<br />

and, oddly enough, to Botticelli’s Spring. There can be no two images<br />

that have less in common than the one of the frozen horses’ heads sticking<br />

out of the ice in the middle of a brutal war and Botticelli’s sugary,<br />

over-the-top, decorative, allegorical vision. Yet I feel that both converge<br />

perfectly into the five horses hanging headless from the wall at the<br />

<strong>Fondation</strong> <strong>Beyeler</strong>. Fear, despair, tragedy, and allegory are combined in<br />

Cattelan’s sensitivity, which has brought him a long way, from being simply<br />

a donkey to feeling like a trapped horse. As I said, Malaparte’s novel<br />

could be enough for us to gain an understanding of Cattelan’s art. I could<br />

easily stop writing here. But instead, I will indulge in an unlikely competition<br />

with Malaparte and pave my own path to Cattelan’s five horses. It<br />

will be a personal chronology with very personal references, far removed<br />

from any scholarly dissertation on Cattelan’s art. For me to talk about<br />

Cattelan like a scholar would be an oxymoron. My story is not linear and<br />

it’s roughly divided into five short chapters, each of which discusses a<br />

work of art that I believe will bring us closer to understanding Cattelan’s<br />

parade of suspended horses. The five horses are somehow different<br />

from the individual horses that Cattelan presented in the past. The lonely<br />

horse is a kind of attempt to escape solitude, a feeling the artist is cons-<br />

Sandro Botticelli, Spring, c. 1482<br />

© 2013. Photo Scala, Florence, Courtesy Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali<br />

tantly fighting. The jump, the effort is delusional and yet heroic. The five<br />

horses transform delusion into panic, they escape in a stampede and the<br />

individual effort in a feverish crowd. It’s an exodus we’re witnessing, not<br />

a search for freedom. Like Malaparte’s horses in Finland that run away<br />

from the burning wood into the frozen lake, Cattelan’s horses do not seek<br />

freedom but survival.<br />

(2)<br />

FIVE DEGREES OF HISTORY<br />

Winter Sunset with a Rider and a Rearing Horse is a painting by Carl<br />

Fredrik Hill (1849–1911), the Swedish painter mentioned above. I do not<br />

know where this painting is and when the artist did it. However, the posture<br />

of the horse is all we need to know, and the sky becomes Cattelan’s<br />

wall: a wall that is the border between winter and spring, between death<br />

and life again. You can read into this as much as you wish, or nothing at<br />

all. Is it just a coincidence? But then, if art is simply a coincidence, why<br />

even bother? Maurizio Cattelan wishes to unsettle us and he’s succeeding,<br />

in his own way. The wall is also a border between the historical and<br />

the mundane, between the souvenir and the trophy, the memory and<br />

the anecdote. All these elements conspire along this obvious and yet<br />

invisible border. Cattelan erases the sunset, the rider is gone, only the<br />

rearing horses remain, beheaded, or maybe not. We are looking at the<br />

animals from under a frozen sheet of ice, waiting patiently for spring to<br />

come and free us.<br />

1994. The Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in southern France is discovered to<br />

contain some of the earliest cave paintings in human history. One of the<br />

most famous paintings is of four horse heads. It is as though Cattelan is<br />

going backwards in time. 32,000 years backwards, looking for the heads<br />

of his horses. 1994. New York. Daniel Newburg Gallery. Warning! Enter at<br />

Carl Fredrik Hill, Winter Sunset with a Rider and a Rearing Horse, 1877<br />

your own risk, Do not touch, Do not feed, No smoking, No photographs,<br />

No dogs, Thank you. This is the title of Cattelan’s first New York exhibition.<br />

A failure. According to him, he felt like a donkey since two previous<br />

projects had been rejected. He showed the donkey, the cousin of the<br />

horse. The five horses are maybe the completion of that long failure that<br />

began almost twenty years ago. The New York gallery was Cattelan’s<br />

cave. The first rock wall on which he bumped his head, where he would<br />

have liked to hide or bury his head. The donkey, not noble enough or not<br />

ready to be sacrificed under the wall of fear.<br />

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 2009, Photo: Zeno Zotti, Courtesy Maurizio Cattelan’s Archive<br />

Venice, Saint Mark’s Cathedral. On its facade, the copies of four copper<br />

horses. The originals are protected inside the basilica. Four horses. Like<br />

those in Chauvet’s cave. It seems like one horse is always missing the<br />

count. Where is the fifth horse? Saint Mark’s horses arrived in 1204 after<br />

the Sack of Constantinople, before which, they had been stolen from<br />

Greece. Nobody knows for sure who the sculptor was, maybe Lysippos.<br />

In 1797, Napoleon took them and placed them on top of the Arc de<br />

Triomphe du Carrousel. They returned to Venice 1815, after the Battle<br />

of Waterloo. The Venetian horses look agitated, they feel they are in<br />

the wrong place. Constantinople, Venice, Paris… They are not at home,<br />

they belong somewhere else, on a Greek island. Their original purpose<br />

was not to celebrate wars, imperial victories or defeats. Cattelan’s five<br />

horses share this feeling with those four but nobler horses. They belong<br />

somewhere else. Art uprooted never fulfills its scope. Cattelan’s work<br />

gives the impression of being somehow uprooted and, like Saint Mark’s<br />

horses, it gains strength from this condition, it gains life from this state<br />

of uneasiness.<br />

1800–1803. Jacques-Louis David. Bonaparte Crossing the Alps. Napoleon<br />

may have been in the Alps with his white Arabian stallion in 1799, but<br />

the four horses of Saint Mark’s had crossed the Alps two years earlier.<br />

David made five versions of this painting. The power of its composition<br />

does not lie in the image of the First Consul and future emperor but in the<br />

balance of his horse, or its resistance to scale that rocky wall that is the<br />

Jacques-Louis David, Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, 1800<br />

© RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles)/Gérard Blot<br />

Great Saint Bernard Pass. Napoleon is not retreating but proceeding in<br />

his conquest of Europe. What is Cattelan doing? Retreating or advancing?<br />

The horses in Chauvet’s cave, Saint Mark’s horses, Napoleon’s<br />

horse, and now Cattelan’s horse and horses. The journey leads through<br />

a complex panorama—one drawn by European civilization, on the one<br />

hand, by merging with a Paleolithic root and on the other by springing<br />

from Byzantium, or a place even deeper in Asia—and recalls Attila’s<br />

legendary horses. Where does all this lead or end, or start again and<br />

again?<br />

Rome, 1969. Galleria l’Attico. Twelve live horses are entering the space.<br />

They will be the subject of Jannis Kounellis’s exhibition. The Surrealist<br />

poet André Breton once spoke about the idea of making something<br />

impossible possible, like the Tartars bringing their horses to drink at the<br />

fountains of Versailles. That’s what Kounellis is doing: making the impossible<br />

possible. In a garage, history is crossing several borders at the<br />

same time. That’s where our story is approaching its conclusion. From<br />

the brutality of Malaparte’s Lake Ladoga and his dead, terrified horses<br />

to the glorious gesture of a parade of live horses entering an industrial<br />

space in Rome. From sheer devastation to sheer celebration. What is<br />

now left of all this if not the five horses of Cattelan, which are neither<br />

alive nor truly dead, but suspended in a state of wonder, crossing<br />

devastation, trespassing celebration, and ending nowhere. Looking for,<br />

seeking out another dimension, another space, another era far beyond<br />

anything we have yet imagined.<br />

In Henri-Georges Clouzot’s movie The Wages of Fear (1953), the character<br />

Mario, played by Yves Montand, and his critically wounded<br />

friend Jo (Charles Vanel) reminisce about a neighborhood they both<br />

know in Paris, near the rue Galande. A fence is mentioned. “I never<br />

knew what was behind it,” utters Jo, between two gasps of agony.<br />

“Nothing,” answers Mario. Seemingly unaware of Mario’s response, Jo<br />

asks again, “What was there behind that fence?” “Nothing, I’m telling<br />

you, nothing.” “There’s nothing,” the man repeats, dying with his eyes<br />

wide open, as if he were already seeing from the other side.<br />

While standing under Cattelan’s horses, the viewer will have the same<br />

question to ask the poor animals before it is too late.<br />

“What do you see on the other side of that wall?”<br />

“Nothing,” or maybe: “Just a donkey.”<br />

Maurizio Cattelan, Warning! Enter at your own risk, Do not touch,<br />

Do not feed, No smoking, No photographs, No dogs, Thank you, 1994,<br />

Photo: Lina Bertucci, Courtesy Maurizio Cattelan’s Archive<br />

FONDATION BEYELEr<br />

Baselstrasse 101, CH-4125 Riehen / Basel,<br />

www.fondationbeyeler.ch