Roads of Arabia

Roads of Arabia

Roads of Arabia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

05 Arabie US p100-109_CM_BAT.qxd 23/06/10 21:23 Page 108<br />

ROADS OF ARABIA<br />

who wished to rival Muhammad. The Medinese caliphs, Muhammad’s direct successors<br />

whom the Muslim tradition designates as “Rightly Guided”, rashidun, all came from<br />

Muhammad’s Meccan tribe. They belonged to his close circle and were his oldest companions.<br />

They were able to preserve the intertribal alliance, albeit recent, which had been<br />

formed. At the cost <strong>of</strong> several battles they soon controlled the entire <strong>Arabia</strong>n peninsula. The<br />

Arab tribes’ first incursions beyond their familiar territory historically conformed to the<br />

peninsula tribes’ traditional forays. But this time – entirely unexpectedly – the initial impetus<br />

led them much further, towards outer lands, whether it be Iraq and Iran ruled at the time<br />

by the Sassanid Persians, or Syria, Palestine and Egypt, tributaries <strong>of</strong> the Byzantine Empire.<br />

However these conquests cannot be claimed to have been in the name <strong>of</strong> religion, as for over<br />

a century and a half after the tribes’ exit from <strong>Arabia</strong> the populations <strong>of</strong> the conquered countries,<br />

who did not belong to the tribal society, were not at all urged to convert to Islam. This<br />

tendency was only discontinued under the dynasty <strong>of</strong> the Baghdad Abbasids who overthrew<br />

the Umayyad caliphs in the mid-8th century.<br />

The great Muslim conquests <strong>of</strong> the second quarter <strong>of</strong> the 7th century seem more like a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> opportunistic raids, which sustained their progression with their successes and<br />

belief in the effective protection <strong>of</strong> a god granting victory. In the east they were aided by the<br />

war <strong>of</strong> succession ravaging the Sassanid Empire which sank without trace. In the west the<br />

conquerors took advantage <strong>of</strong> the difficulties the Byzantine Empire encountered in the<br />

management, in particular religious, <strong>of</strong> the Near East populations. The progression <strong>of</strong> the<br />

conquests was halted for ten years or so under the Medinese caliphate due to internecine<br />

conflicts. They show the difficulties encountered by the men <strong>of</strong> the tribe, in such a short<br />

lapse <strong>of</strong> time, in governing societies and territories which in no way resembled the collective<br />

living conditions they knew in their native habitat. The Meccan family <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Umayyads triumphed over what we might describe as an adaptation crisis and growing<br />

pains. Henceforth settled in Damascus, which became the political capital <strong>of</strong> the caliphate,<br />

it pursued the Muslim expansion until the 7th century. This empire extended from the<br />

Iberian Peninsula, which was almost entirely controlled, all the way to the great steppe <strong>of</strong><br />

the plains <strong>of</strong> Central Asia and the eastern part <strong>of</strong> the Iranian dominion, present-day<br />

Afghanistan, including all the territories <strong>of</strong> the southern coast <strong>of</strong> the Mediterranean and<br />

temporarily some <strong>of</strong> its islands, such as Sicily. The Damascus Umayyads directly governed<br />

this huge empire for over a century. However in the early days <strong>of</strong> the dynasty a second<br />

internecine conflict arose involving in particular the two prophetic cities <strong>of</strong> Mecca and<br />

Medina. In fact the caliph Yazid, son and successor <strong>of</strong> Mu‘awiya, founder <strong>of</strong> the dynasty,<br />

as soon as he began his reign in 680 had to grapple with the revolt <strong>of</strong> several important<br />

Meccan families who refused to yield the monopoly <strong>of</strong> caliphal power to the Umayyad<br />

clan. The uprising, led by the Zubayrid family, was crushed in 693. Mecca was not spared;<br />

during the various assaults <strong>of</strong> the caliph’s troops, catapults were used, destroying in part<br />

the Ka‘ba, which was subsequently devastated by a fire. The rebel Abd Allah, son <strong>of</strong> al-<br />

Zubayr, who still occupied the city, had the edifice rebuilt with countless precautions,<br />

fearful <strong>of</strong> incurring a divine curse. The Black Stone, al-hajar al-aswad, the holy stone,<br />

placed in the east corner <strong>of</strong> the building, had been broken in three pieces. It was returned<br />

to its place and mounted in a silver ring. The Umayyads having seized the city restored<br />

the edifice and its immediate surroundings to their original configuration – which had<br />

been altered by the Zubayrid, who had included in its north-west part the semi-circular<br />

area called hijr containing, according to some traditions, the tombs <strong>of</strong> Ishmael and his<br />

mother, Agar.<br />

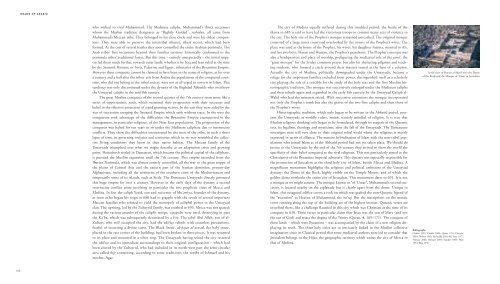

The city <strong>of</strong> Medina equally suffered during this troubled period: the battle <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Harra in 683 is said to have led the victorious troops to commit many acts <strong>of</strong> violence in<br />

the city. The holy site <strong>of</strong> the Prophet’s mosque remained unscathed. The original mosque<br />

consisted <strong>of</strong> a large inner courtyard overlooked by the rooms <strong>of</strong> the Prophet’s wives. The<br />

place was used as the home <strong>of</strong> the Prophet, his wives, his daughter Fatima, married to Ali,<br />

and her two boys, Hasan and Husayn, the Prophet’s grandsons. The Prophet’s mosque was<br />

also a headquarters and place <strong>of</strong> worship, prefiguring the mediaeval role <strong>of</strong> the jami’, the<br />

“great mosque” for the Friday common prayer but also for sheltering pilgrims and teaching<br />

students, who formed a circle around their masters seated at the base <strong>of</strong> a column.<br />

Actually the city <strong>of</strong> Medina, politically downgraded under the Umayyads, became a<br />

refuge for the important families excluded from power, distinguished itself as a scholarly<br />

city playing the role <strong>of</strong> a crucible for the study <strong>of</strong> the holy text and the first Muslim historiographic<br />

tradition. The mosque was successively enlarged under the Medinese caliphs<br />

and then rebuilt again and expanded in the early 8th century by the Umayyad Caliph al-<br />

Walid who had the minarets raised. With successive extensions the mosque incorporated<br />

not only the Prophet’s tomb but also the graves <strong>of</strong> the two first caliphs and then those <strong>of</strong><br />

the Prophet’s wives.<br />

Historiographic tradition, which only began to be written in the Abbasid period, presents<br />

the Umayyads as worldly rulers, muluk, scarcely mindful <strong>of</strong> religion. It is true that<br />

Muslim religious thinking only began to be formulated, through its exegesis <strong>of</strong> the Quranic<br />

text, its legalism, theology and mysticism, after the fall <strong>of</strong> the Umayyads. The Damascene<br />

sovereigns were still very close to their original tribal world where the religious is mostly<br />

expressed in terms <strong>of</strong> alliance. The massive hybridization <strong>of</strong> Islam with the non-tribal populations<br />

who joined Islam as <strong>of</strong> the Abbasid period had not yet taken place. We should do<br />

justice to the Umayyads: by the end <strong>of</strong> the 7th century they strived to show the world the<br />

specificity <strong>of</strong> their belief compared to the rival religions. This was particularly aimed at the<br />

Christianity <strong>of</strong> the Byzantine imperial adversary. This dynasty was especially responsible for<br />

the promotion <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem as the third holy city <strong>of</strong> Islam, beside Mecca and Medina. A<br />

magnificent monument highlights the religious and political ambitions <strong>of</strong> the Umayyad<br />

dynasty: the Dome <strong>of</strong> the Rock, highly visible on the Temple Mount, and <strong>of</strong> which the<br />

golden dome overlooks the entire city <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem. This monument dates to 691. It is not<br />

a mosque as we might assume. The mosque known as “<strong>of</strong> ‘Umar”, Muhammad’s second successor,<br />

is located nearby on the esplanade but is clearly apart from the dome. Unique in<br />

Islam, this octagonal edifice covers a rock on which was grafted the non-Quranic legend <strong>of</strong><br />

the “ascension” to Heaven <strong>of</strong> Muhammad, the mi’raj. But the inscriptions on the mosaic<br />

cover running along the top <strong>of</strong> the building are <strong>of</strong> the highest interest. Quranic verses are<br />

inscribed there, like a challenge flaunted in this city which was Christian at the time <strong>of</strong> its<br />

conquest in 638. These verses in particular claim that Jesus was the son <strong>of</strong> Mary (and not<br />

the son <strong>of</strong> God) and reject the dogma <strong>of</strong> the Trinity (Quran, 4, 169–171). The conquest <strong>of</strong><br />

these lands – which were Byzantine – was accompanied by the claim <strong>of</strong> a new religion displaying<br />

its truth. The three holy cities are so intricately linked in the Muslim collective<br />

imagination since its Classical period that some mediaeval authors were led to consider that<br />

Jerusalem belongs to the Hijaz, the geographic territory which unites the city <strong>of</strong> Mecca to<br />

that <strong>of</strong> Medina.<br />

Aerial view <strong>of</strong> Haram al-Sharif with the Dome<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Rock and the Mosque <strong>of</strong> ‘Umar in Jerusalem<br />

Bibliography:<br />

Chabbi 1997; Chabbi 2008; Quran 1955; Déroche<br />

2009; Donner 1981; McAuliffe 2001–06; Paret 1977;<br />

Prémare 2002; Prémare 2004; Sourdel 1968; Watt<br />

1953; Watt 1956.<br />

108