Roads of Arabia

Roads of Arabia

Roads of Arabia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

07 Arabie US p118-131_BAT.qxd 23/06/10 21:29 Page 126<br />

ROADS OF ARABIA<br />

Languages and Scripts<br />

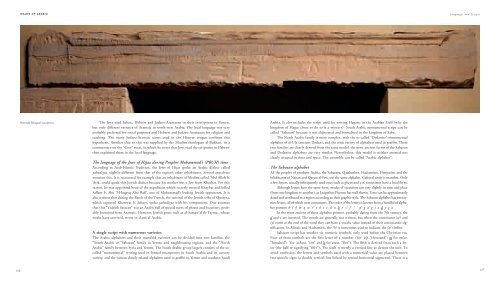

Rawwafa bilingual inscription.<br />

The Jews used Sabaic, Hebrew and Judaeo-Aramaean in their inscriptions in Yemen,<br />

but only different varieties <strong>of</strong> Aramaic in north-west <strong>Arabia</strong>. The local language was very<br />

probably preferred for social purposes and Hebrew and Judaeo-Aramaean for religion and<br />

teaching. The many Judaeo-Aramaic terms used in the Himyar tongue confirms this<br />

hypothesis. Another clue to this was supplied by the Muslim theologian al-Bukhari, in a<br />

commentary on the “Cow” surat, in which he notes that Jews read the scriptures in Hebrew<br />

then explained them in the local language.<br />

The language <strong>of</strong> the Jews <strong>of</strong> Hijaz during Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) time<br />

According to Arab-Islamic Tradition, the Jews <strong>of</strong> Hijaz spoke an Arabic dialect called<br />

yahudiyya, slightly different from that <strong>of</strong> the region’s other inhabitants. Several anecdotes<br />

mention this. It is recounted for example that an inhabitant <strong>of</strong> Medina called ‘Abd Allah b.<br />

‘Atik, could speak this Jewish dialect because his mother was a Jew from Khaybar. For this<br />

reason, he was appointed head <strong>of</strong> the expedition which secretly entered Khaybar and killed<br />

Sallam b. Abu ‘l-Huqayq Abu Rafi‘, one <strong>of</strong> Muhammad’s leading Jewish opponents. It is<br />

also written that during the Battle <strong>of</strong> the Trench, the sentinel <strong>of</strong> the Jewish tribe <strong>of</strong> Qurayza,<br />

which captured Khawwat b. Jubayr, spoke yahudiyya with his companions. One assumes<br />

that this “Yiddish Saracen” was an Arabic full <strong>of</strong> special turns <strong>of</strong> phrase and locutions, probably<br />

borrowed from Aramaic. However, Jewish poets such as al-Samaw’al de Tayma , whose<br />

works have survived, wrote in classical Arabic.<br />

A single script with numerous varieties<br />

The Arabic alphabets and their manifold varieties can be divided into two families, the<br />

“South Arabic or “Sabaean” family in Yemen and neighbouring regions, and the “North<br />

Arabic” family between Syria and Yemen. The South Arabic group largely consists <strong>of</strong> the socalled<br />

“monumental” writing used in formal inscriptions in South <strong>Arabia</strong> and its cursory<br />

variety, and the various closely related alphabets used in graffiti in Yemen and southern Saudi<br />

<strong>Arabia</strong>. It also includes the script used for writing Hagaric in the <strong>Arabia</strong>n Gulf (why the<br />

kingdom <strong>of</strong> Hagar chose to do so is a mystery). South Arabic monumental script can be<br />

called “Sabaean” because it was elaborated and formalized in the kingdom <strong>of</strong> Saba.<br />

The North Arabic family is more complex, with the so-called “Dedanite” monumental<br />

alphabet <strong>of</strong> al-Ula (ancient Dedan), and the wide variety <strong>of</strong> alphabets used in graffiti. These<br />

two families are clearly derived from the same model: the most ancient forms <strong>of</strong> the Sabaean<br />

and Dedanite alphabets are very similar. Nevertheless, this model is neither attested nor<br />

clearly situated in time and space. The ensemble can be called “Arabic alphabet”.<br />

The Sabaean alphabet<br />

All the peoples <strong>of</strong> southern <strong>Arabia</strong>, the Sabaeans, Qatabanites, Hadramites, Himyarites and the<br />

inhabitants <strong>of</strong> Najran and Qaryat al-Faw, use the same alphabet. Cultural unity is manifest. Only<br />

a few letters, usually infrequently used ones such as ghayn and ẓ a’, sometimes have a local form.<br />

Although letters have the same form, modes <strong>of</strong> execution can vary slightly in time and place<br />

(from one kingdom to another), as Jacqueline Pirenne has well shown. Texts can be approximately<br />

dated and attributed to a region according to their graphic style. The Sabaean alphabet has twentynine<br />

letters, all <strong>of</strong> which note consonants. The order <strong>of</strong> the letters is known from a handful <strong>of</strong> alphabet<br />

primers: h l ḥ m q w s 2 r b t s 1 k n h ṣ s 3 f ’ ‘ ḍ g d g ṭ z d y t ẓ<br />

In the most ancient <strong>of</strong> these alphabet primers, probably dating from the 7th century, the<br />

d and z are inverted. The vowels are generally not written, but when the consonants /w/ and<br />

/y/ come at the end <strong>of</strong> the word they can have a vocalic value instead <strong>of</strong> their consonantic signification.<br />

In Minaic and Hadramitic, the /h/ is sometimes used to indicate the /a/ timbre.<br />

Sabaean script has another six numeric symbols, only used before the Christian era.<br />

Four <strong>of</strong> these symbols are the first letter <strong>of</strong> a number (’for ’alf, “thousand”; m for mi’at,<br />

“hundred”; ‘ for ‘ashara, “ten” and h for amsa, “five”). The fifth is derived from such a letter<br />

(the half-m signifying “fifty”). The sixth is merely a vertical line to denote the unit. To<br />

avoid confusion, the letters and symbols used with a numerical value are placed between<br />

two specific signs (a double vertical line linked by several horizontal segments). There is a<br />

126<br />

127