Download Publication - Rio+20

Download Publication - Rio+20

Download Publication - Rio+20

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ISSN 1809-8185<br />

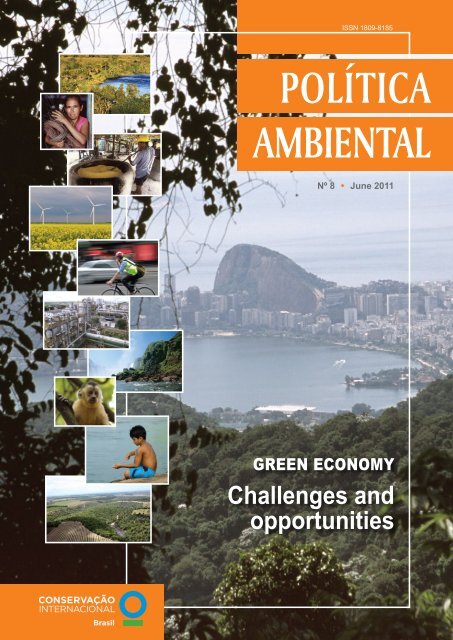

POLÍTICA<br />

AMBIENTAL<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

green economy<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities

2<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Conservação Internacional is a private non-profit organization,<br />

founded in 1987, with the objective of promoting human well-being by<br />

strengthening society’s role in the responsible and sustainable care<br />

of nature – our global biodiversity – supported by a solid foundation in<br />

science, partnerships and field experiences.<br />

President: José Alexandre Felizola Diniz-Filho<br />

Executive Director: Fábio Scarano<br />

Director of Environment Policy: Paulo Gustavo Prado<br />

Director of Communications: Isabela de Lima Santos<br />

Conservação Internacional<br />

Av. Getúlio Vargas, 1300, 7º andar<br />

30112-021 Belo Horizonte MG<br />

tel.: 55 31 3261-3889<br />

e-mail: info@conservacao.org<br />

www.conservacao.org<br />

Política Ambiental is an electronic journal issued by Conservation<br />

International that publishes scientific and technical articles about the<br />

main topics of current environmental policy.<br />

Política Ambiental<br />

Green economy: challenges and opportunities<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Editorial coordination: Camila L. Gramkow<br />

Paulo Gustavo Prado<br />

Coordination of edition: Gabriela Michelotti<br />

Translation: Cecília Barsk Romero<br />

(Pages 24 to 35, 96 to 107, 120 to 126 - Elza Suely Anderson)<br />

(Pages 86 to 95, 108 to 119 - Janaína Mendes)<br />

Cover photographs: Larger photograph: © CI/Haroldo Castro Smaller<br />

photographs (top down): © CI/Luciano Candisani,<br />

© CI/Luciano Candisani, © CI/M. de Paula, Wild Wonders of<br />

Europe/Laszlo Novak, iStockphoto, Cortesia UNICA,<br />

© CI/John Martin, © CI/Sterling Zumbrunn,<br />

© CI/Enrico Bernard and © CI/Christine Dragisic<br />

Design and graphic editing: Grupo de Design Gráfico Ltda.<br />

Catalog card prepared by Librarian Nina C. Mendonça CRB6/1288<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

P769<br />

Política Ambiental / Conservação Internacional - n. 8, jun. 2011 – Belo<br />

Horizonte: Conservação Internacional, 2011.<br />

n. 1 (maio 2006)<br />

ISSN 1809-8185<br />

1. Política ambiental – Periódicos. I. Conservação Internacional Brasil.

3<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

content<br />

Acronyms ............................................................................................................. 4<br />

Preface ................................................................................................................. 6<br />

Executive Summary ............................................................................................ 9<br />

Delineations of a green economy<br />

Helena Pavese ..................................................................................................... 16<br />

The necessarily systemic character of the transition to a green economy<br />

Alexandre D’Avignon and Luiz Antônio Cruz Caruso ............................................ 24<br />

Green economy and/or sustainable development?<br />

Donald Sawyer ..................................................................................................... 36<br />

International perspectives of the transition to a low-carbon green economy<br />

Eduardo Viola ....................................................................................................... 43<br />

Green economy in Latin America: the origins of debate in ECLAC work<br />

Márcia Tavares ..................................................................................................... 57<br />

The role of inclusive growth for a green economy in developing countries<br />

Clóvis Zapata ....................................................................................................... 69<br />

Brazil and the green economy: a panorama<br />

Francisco Gaetani, Ernani Kuhn and Renato Rosenberg ..................................... 76<br />

Growth potential of the green economy in Brazil<br />

Carlos Eduardo F. Young ..................................................................................... 86<br />

Brazil and the green economy: foundations and strategy for transition<br />

Cláudio Frischtak ................................................................................................. 96<br />

Innovation and technology for a green economy: key issues<br />

Maria Cecília J. Lustosa ...................................................................................... 108<br />

Agriculture for a green economy<br />

Ademar R. Romeiro ............................................................................................. 120<br />

Green economy and a new cycle of rural development<br />

Arilson Favareto ................................................................................................... 127<br />

Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest: causes and solutions<br />

Bastiaan P. Reydon .............................................................................................. 138<br />

The transition to a green economy in Brazilian law:<br />

perspective and challenges<br />

Carlos Teodoro Irigaray ........................................................................................ 151<br />

Market mechanisms for a green economy<br />

Peter H. May ........................................................................................................ 165<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Valuation and pricing of environmental resources for a green economy<br />

Ronaldo Seroa da Motta ...................................................................................... 174<br />

The role of financial institutions in the transition to a green economy<br />

Mário Sérgio Vasconcelos .................................................................................... 186<br />

Measurement in policies for transition to a green economy<br />

Ronaldo Seroa da Motta and Carolina Dubeux .................................................... 192

4<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

acronyms<br />

BASIC – Brazil, South Africa, India and China<br />

BNDES – National Bank of Economic and Social Development<br />

BRIC – Brazil, Russia, India and China<br />

CNI – National Industrial Confederation<br />

CU – Conservation Unit<br />

ECLAC – Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean<br />

EMBRAPA – Brazilian Agricultural Research Company<br />

GDP – Gross Domestic Product<br />

GE – Green Economy<br />

GMO – Genetically Modified Organism<br />

FAO – United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization<br />

FEBRABAN – Brazilian Federation of Banks<br />

GHG – Greenhouse Gases<br />

HIV/AIDS – Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency<br />

syndrome<br />

IBAMA – Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural<br />

Resource<br />

IBSA – India, Brazil, South Africa<br />

IBGE – Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics<br />

ICMBio – The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation<br />

Imazon – Amazon Institute of People and the Environment<br />

INCRA – National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform<br />

INPE – National Institute for Space Research<br />

IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change<br />

IPC-IG - International Policy Center for Inclusive Growth<br />

IPEA – Institute of Applied Economic Research<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

MCT – Ministry of Science and Technology<br />

MDA – Ministry of Agrarian Development<br />

Mercosul – Southern common market

5<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Siglário<br />

MMA – Ministry of the Environment<br />

MME – Ministry of Mines and Energy<br />

NGO – Non-Governmental Organization<br />

OECD – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development<br />

OTCA – Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization<br />

R&D – Research and Development<br />

PES – Payment for Environmental Services<br />

REDD – Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation<br />

REDD+ – Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation,<br />

including conservation, sustainable forest management, afforestation and<br />

re-forestation.<br />

Rio 92 – United Nations Conference on Environment and Development<br />

Rio+10 – World Summit on Sustainable Development that took place in 2002<br />

in Johannesburg<br />

<strong>Rio+20</strong> – United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development that will<br />

be held in 2012 in Rio de Janeiro<br />

TEEB – The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity<br />

UN – United Nations<br />

UNASUR – Union of South American Nations<br />

UNIDO – United Nations Industrial Development Organization<br />

UNDP – United Nations Development Programme<br />

UNEP – United Nations Environment Programme<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011

6<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Preface<br />

Environmental issues have become increasingly incorporated in the<br />

scientific agendas of the most diverse fields of knowledge and in local, national,<br />

regional and global political agendas. Its growing relevance originates from the<br />

widespread understanding that environmental sustainability is indispensable<br />

to the long term development of societies. On one hand, from an alarmist<br />

perspective, neglecting this issue would probably result in perverse effects on<br />

human beings and development, as pointed out currently by many studies 1 .<br />

From a strategic perspective, possibilities and opportunities have been identified<br />

deriving from its effective incorporation, once it could contribute to achieving<br />

more sustainable development processes in various dimensions (economic,<br />

social and environmental) 2 .<br />

The challenge of moving towards a more egalitarian and sustainable society<br />

is, more than ever, on the agenda. It is in this context that the green economy<br />

concept has emerged. Defined by the UNEP as that which “results in improved<br />

human well-being and social equality, while significantly reducing environmental<br />

risks and ecological scarcity” 3 , green economy will be one of the key topics 4<br />

of <strong>Rio+20</strong>, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development that<br />

will take place in 2012 in Rio de Janeiro.<br />

The challenge is not simple and discussions are only beginning. Despite<br />

having a formal conceptualization, precise delineations are still to be determined.<br />

After all, what is a green economy? Which economies are closer to reaching it?<br />

How to measure the degree of “greening” of an economy? What does it mean,<br />

concretely, to achieve transition to a green economy? What is the role of the<br />

state in this transition? How to finance the transition? Which sectors will be<br />

most affected? Which will be most benefitted? How would the transition affect<br />

the daily lives of citizens? What are the risks of not transforming to a green<br />

economy? And in the case of Brazil, what has the country done and what is<br />

left to do to advance towards a green economy? How is the country doing,<br />

compared to the others? What are the main obstacles and challenges? How to<br />

address them? What would a transition mean for society, productive sectors,<br />

for government, for consumers? How can developed and developing countries<br />

cooperate in this transition? How can international promotion and cooperation<br />

organizations align themselves with these objectives? How can United Nations<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

1. In global terms, see Stern (2007) and IPCC (2007). For an analysis of the Brazilian case, see<br />

World Bank (2010), Marcovitch (coord.) (2010) and NAE (2005).<br />

2. TEEB (2011) and UNEP (2011).<br />

3. UNEP (2011).<br />

4. The two key topics to guide the Conference are: (i) green economy in the context of<br />

sustainable development and poverty eradication; and (ii) institutional framework for<br />

sustainable development.

7<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Preface<br />

priority international initiatives, such as the Climate Change and the Biodiversity<br />

Conventions, encourage and implement common agendas aimed at achieving<br />

these objectives?<br />

Green economy raises many questions that do not have simple and straight<br />

answers. We know, however, that the transition requires substantial efforts<br />

and engagement from all segments of society, especially government and the<br />

private sector. It demands that governments level the playing field for greener<br />

products by removing perverse incentives, revising policies and incentives,<br />

strengthening market infrastructure, introducing new market mechanisms,<br />

redirecting public investment and “greening” public procurement. The private<br />

sector, on the other hand, will need to respond to these policy reforms through<br />

increased financing and investments, as well as by creating innovation skills<br />

and capabilities to make the best of green economy opportunities.<br />

The timing to discuss an alternative paradigm, where the generation of<br />

wealth does not increase social disparities or produce environmental risks,<br />

nor ecological scarcities, could not be more opportune. The 2008 crisis, from<br />

which the global economy is still trying to recover, could be an opportunity to<br />

think about and formulate the economic model that we wish to follow.<br />

The transition to a green economy could benefit Brazil in various ways. The<br />

green economy demands greater social equity, something that is especially<br />

necessary in Brazil, which is among the ten countries with the worst income<br />

distribution on the planet 5 . The transition could, thus, serve as a platform for<br />

poverty eradication. Furthermore, Brazil has greatly favorable natural conditions:<br />

the richest biodiversity on the planet, ample water resources, large continental<br />

and coastal areas, ocean resources yet to be discovered; that is, a natural that<br />

albeit threatened is still abundant. In a green economy, natural capital becomes<br />

an asset that generates dividends and produces a competitive edge. Thus, the<br />

pre-requisites are in place that enable Brazil to be more than a beneficiary, but<br />

rather capable of leading the green economy transition, and assuming a role<br />

as global agent for change.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Change can already be seen in various parts of the world 6 . The transition to<br />

a green economy is both a global and a national movement, where cooperation<br />

and coordination are paramount. The reversal of the processes of natural capital<br />

loss and increased social inequality require the efforts of all nations. These<br />

efforts tend to convert themselves into competitive advantages, a situation that<br />

already has become reality in some economies and sectors today. Developing<br />

countries, as keepers of a large portion of the planet’s natural capital, could<br />

exercise a more strategic role. Developed countries, despite already having<br />

consumed a large share of their natural capital, are developing significant<br />

5. UNDP (2010).<br />

6. TEEB (2011).

8<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Preface<br />

advances in so-called green technologies, which tend to be a differential.<br />

Political, technical, scientific-technological, financial and economic cooperation<br />

between the two, in the more than necessary race towards a green economy,<br />

could generate mutual benefits.<br />

This special edition presents ideas for advancing in the direction of a green<br />

economy. It brings reflections from some of the main Brazilian specialists – and<br />

‘Brazilianists’ – on the subject, in a search to respond to the key questions raised<br />

by the green economy in general and in a country such as Brazil. Eighteen<br />

articles gather the contributions of experts from diverse affiliations and origins.<br />

Elements that may form the basis for the green economy discussion in Brazil<br />

are hereby released.<br />

Enjoy the reading!<br />

References<br />

World Bank (2010). Estudo de baixo carbono para o Brasil. Available at: .<br />

IPCC (2007). IPCC fourth assessment report: climate change 2007. Available at: .<br />

Marcovitch, Jacques (coord.) (2010). Economia da mudança do clima no Brasil: custos<br />

e oportunidades. São Paulo: IBEP Gráfica.<br />

NAE - Núcleo de Assuntos Estratégicos da Presidência da República (2005). Cadernos<br />

NAE, série mudança do clima, n. 3, February. Brasília: Núcleo de Assuntos<br />

Estratégicos da Presidência da República, Secretaria de Comunicação de Governo<br />

e Gestão Estratégica.<br />

Stern, Nicholas (2007). The Economics of Climate Change: the Stern review. Cambridge:<br />

Cambridge University Press.<br />

TEEB (2011). The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: mainstreaming the<br />

economics of nature: a synthesis of the approach, conclusions and recommendations<br />

of TEEB. Available at: .<br />

UNDP (2010). Actuar sobre el futuro: romper la transmisión intergeneracional de la<br />

desigualdad. Informe regional sobre desarrollo humano para América Latina y el<br />

Caribe 2010. New York: UNDP.<br />

UNEP (2011). Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and<br />

Poverty Eradication - A Synthesis for Policy Makers. Available at: .<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011

9<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Executive Summary<br />

The first article, written by Helena Pavese, puts forth the concept of green<br />

economy and main results of the report “Towards a green economy: pathways to<br />

sustainable development and poverty eradication”, launched in February 2011.<br />

Starting from the finding of elevated levels of ecosystem services degradation<br />

and, therefore, of natural capital, the author presents the Green Economy<br />

Initiative, launched with the intention of identifying the social and economic<br />

risks and costs generated by current standards of excessive natural resource<br />

use, as well as the opportunities for a transition to more sustainable practices.<br />

From this Initiative, the Report on green economy emerged, whose main results<br />

Pavese succinctly outlines. It is concluded that green economy is possible and<br />

desirable, as it is capable of aligning income and employment generation with<br />

poverty eradication and natural capital conservation.<br />

Alexandre D’Avignon and Luiz Antônio Cruz Caruso analyze the UNEP report<br />

from a critical perspective. They affirm that the Report represents a qualitative<br />

leap in the sense of introducing values that go beyond maximizing utility.<br />

They reveal the necessity of thinking about the green economy transition in a<br />

systemic way, where human activities are merely a subsystem of civil society,<br />

which in turn is a subsystem of the universe (or the biosphere and its set of<br />

living and inanimate matter). They argue that other theoretical lines, in addition<br />

to the neo-classical theory, can provide important insights about the issues<br />

in question. Ecologic economics would offer a more systemic approach and<br />

schumpeterian and neo-schumpeterian theories could assist in rethinking the<br />

economy from the perspective of technology as a vector of transformation of<br />

human societies. These approaches give consideration to alternative solutions<br />

that are flexible and of a local character, and conducive to an effective transition<br />

to a green economy.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Donald Sawyer analyzes the relationship between green economy and<br />

sustainable development concepts. Sawyer draws attention to the risk of<br />

green economy acquiring an exclusively economic (or economistic) shape,<br />

where market instruments and pricing of natural resources would prevail to<br />

the detriment of measures of a different nature. Thus, Sawyer asserts that<br />

other dimensions are relevant to the green economy, such as social, ethical,<br />

cultural, political and judicial, etc. The author claims that the green economy<br />

should necessarily be public in a greater sense, implemented through policies<br />

that guarantee rights to all and maintain ecosystem functions interlinked, so that<br />

this concept becomes concrete, instrumental and popular, in complementarity<br />

to and connection with the sustainable development concept, that is more<br />

abstract, diplomatic and governmental.

10<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Executive Summary<br />

Eduardo Viola presents a panorama of current international circumstances in<br />

terms of transition to a green economy with a focus on low-carbon characteristics.<br />

Based on recent GHG emissions data of large and medium powers, Viola<br />

presents the main policies and measures that these groups of countries have<br />

practiced, and indicates future prospects based on the current juncture. The<br />

large powers, the United States, China and the European Union, are countries<br />

that: provide elevated contributions to global emissions, possess essential<br />

technological and human capital for decarbonizing the economy and have veto<br />

power over international agreements. The medium powers, such as India and<br />

Brazil, have limited influence on the aspects considered. A similar exercise<br />

is carried out for South America in particular, where the triple negative effect<br />

of deforestation in the region (loss of natural heritage, informality and public<br />

demoralization) and the favorable position of the region, whose economies are<br />

not extensively based on fossil fuels, with some exceptions, are highlighted.<br />

The author also surveys the main techno-economic vectors of a low-carbon<br />

transition, and concludes with a reflection on future prospects.<br />

Márcia Tavares surveys the main contributions of ECLAC to the green<br />

economy field due to its role in drafting documents and leading research and<br />

through its function as political mediator for the Latin American and Caribbean<br />

countries in international discussions. The author describes, in chronological<br />

order, the documents produced and their political and historical contexts.<br />

Tavares argues that these documents enable us to evaluate the complexity<br />

of environmental problems in the region and their direct links with economic<br />

and social structures and processes, an indispensable step to advance in<br />

solving the environmental, economic and social problems of the region. It is<br />

concluded that in order for Latin America to effectively transition to a green<br />

economy, there must be coordination between actors and institutions in different<br />

spheres, removal of barriers to change and strong and permanent institutions<br />

that prioritize sustainability.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Clóvis Zapata highlights the role of inclusive growth in the transition to a<br />

green economy in developing countries. The author starts from the observation<br />

that there are similarities between the UNEP green economy concept and the<br />

concept of inclusive growth. Zapata defends a holistic approach in which the<br />

transition to a green economy should be thought out and planned according to<br />

its various dimensions (environmental, social, economic, political, etc), which<br />

have different windows of opportunity that should be taken into appropriate<br />

consideration. The author argues that policies of a social nature and policies<br />

of an environmental nature have not been sufficiently coordinated, when in<br />

fact, they should act in complementarity. Zapata asserts that promotion of<br />

structured policies is necessary, as exemplified by the analysis of the Brazilian<br />

Biodiesel Program. The author also highlights the importance of South-South<br />

debate, and concludes with a reflection on the importance of inclusive growth

11<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Executive Summary<br />

and the contributions of international organizations and the private sector to<br />

the transition to a green economy in developing countries.<br />

Francisco Gaetani, Ernani Kuhn and Renato Rosenberg provide an overview<br />

of the situation in Brazil with regards to green economy. They argue that Brazil<br />

is an environmental energy power, due to the abundant availability of natural<br />

resources and policies and measures aimed at environmental conservation.<br />

From an international perspective, the authors claim that the country has one<br />

of the highest GHG emissions in the world, but that Brazil is changing this<br />

situation by assuming voluntary emissions reduction targets. They outline the<br />

main actions that Brazil has been implementing in the direction of a green<br />

economy in sectors such as forestry, solid waste treatment, water resources,<br />

among others. The main challenges of the transition are also presented. The<br />

authors conclude that Brazil starts from a privileged position in the transition to<br />

a green economy from various aspects, but that most of the current actions can<br />

be considered as the beginning of the institutional structuring and creation of<br />

economic mechanisms that compose the agenda of a country that is increasingly<br />

focused on the development of markets related to a green economy.<br />

Carlos Eduardo F. Young carries out analytical exercises that aim to study the<br />

impact of a “greening” of Brazilian economy, that is, the transition to a growth<br />

model driven by sectors with low environmental impacts, on the economic and<br />

social performance of the country. Based on the finding that, over the past ten<br />

years, there has been a re-specialization in primary products of Latin American<br />

and Brazilian export bundles, Young shows evidence that there has also been<br />

a specialization in pollution, since the sectors with the most pollution potential<br />

have grown above average. From the results of an input-output matrix model,<br />

the author arrives at the conclusion that the greening of the Brazilian economy<br />

could bring better results in employment and income generation than the current<br />

model specialized in exporting natural resources through predatory extraction<br />

or industrial goods with high levels of pollution in production processes. The<br />

author concludes that, based on the results obtained, the dichotomy between<br />

economic growth and environmental conservation is false.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Cláudio Frischtak analyzes the foundations and strategies of the transition to<br />

a green economy in Brazil. The author starts with the proposal that this transition<br />

requires an inversion of the dominating logic that well-being and intensive (and<br />

unsustainable) use of natural resources are inseparable; and adopt the idea<br />

that higher growth becomes (necessarily) dependent on and is accompanied<br />

by increased conservation or sustainable resource use. Frischtak develops an<br />

analytical structure composed of supply (market or structured) and demand<br />

(induced or spontaneous), that results in a 2x2 matrix. From that analytical<br />

structure, the transition towards a green economy is analyzed with a focus on<br />

certain topics (ecosystem conservation, transportation, sanitation, energy and<br />

product life-cycles). The author also proposes transition strategies based on the

12<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Executive Summary<br />

establishment of a working group, a reference framework, a set of norms and the<br />

restoration of natural capital. It is concluded that a new paradigm is emerging<br />

and that, with support from adequate government policies, Brazil is fully capable<br />

of being one of the first countries to enter into a green economy.<br />

Maria Cecília J. Lustosa analyzes the importance of environmental<br />

innovations as means of changing the current technological model, intensive<br />

in raw materials and energy from fossil fuels, in a more ecologically correct<br />

direction. Lustosa presents the historical emergence of environmental issues<br />

and their relations to economic production. Then, the author highlights the<br />

importance of the innovative process in technological change and paradigm shift,<br />

and presents the circumstances under which such changes could occur and in<br />

which directions, with a focus on EST (Environmentally Sound Technologies).<br />

Internal and external constraints of the capabilities of businesses to become<br />

innovative are also presented. Lustosa further conducts analysis of innovation<br />

linked to environmental issues in Brazilian businesses, and identifies its main<br />

characteristics. Ultimately, the author concludes that environmental innovations<br />

are necessary to enter into a green economy and that building business capacity<br />

is fundamental, and when appropriate, associated with incentives promoted<br />

by the State. In the case of Brazil, low innovation investment in the productive<br />

sector is certainly a factor that further inhibits the search for environmental<br />

innovation.<br />

Ademar R. Romeiro investigates the topic of agriculture in a green economy.<br />

The work offers a description of what agriculture should be in a green economy.<br />

Romeiro begins with the definition of what is understood as green economy from<br />

the perspective of a given long-term sustainability concept, and moves on to<br />

presenting the conditions for making agriculture compatible with this definition of<br />

a green economy. The author seeks to show that an agriculture that is sufficiently<br />

productive to attend to current agricultural production needs is scientifically<br />

and technologically possible, but is chiefly based on management by farmers<br />

of the very forces of nature in order to obtain ecosystem services. The main<br />

agricultural policy recommendation that results from the analysis is to amplify<br />

agro-ecological research efforts by the large public research institutions.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Arilson Favareto brings the new cycle of rural development topic to the<br />

discussion, by analyzing how it aligns with the green economy. The new cycle<br />

of rural development, happening at different intensities around the world and<br />

whose distinguishing feature is the transition from an agrarian and agricultural<br />

paradigm to a paradigm organized around the environmental rooting of<br />

rural development, is in line with the transition to a green economy. Modern<br />

agriculture, intensive in natural resource use, generates a lot of income but<br />

little employment. Favareto presents the main characteristics of new rurality<br />

and analyzes the situation in Brazil, identifying that here, as in the rest of the<br />

world, agriculture has a declining tendency in relation to other activities and

13<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Executive Summary<br />

that rural regions are no longer experiencing a general exodus, but rather a<br />

heterogeneity of its demographic profile, with elevated levels of schooling and<br />

greater social differentiation. The author concludes with ideas for an agenda<br />

that aligns this new cycle with the transition to a green economy.<br />

Bastiaan P. Reydon conducts an analysis of the causes of and solutions to<br />

deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Reydon begins by presenting data on<br />

deforestation in the Amazon, and highlights the main causes attributed to this<br />

deforestation. The author argues that deforestation results from the continued<br />

tradition of expanding the Brazilian agricultural frontier, which generally takes<br />

the following steps: occupation of virgin land (private or public), extraction of<br />

hardwood, installation of livestock farming and, ultimately, development of<br />

modern farming and cattle raising. Reydon proposes that land speculation is<br />

the principal engine of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, and presents<br />

empirical data that deforestation is associated with land valuation. The author<br />

conducts an analysis of the Amazon land tenure situation in its various<br />

categories, pointing to the inability of the Brazilian state to govern over the<br />

lands in the region. The reasons for which the land issue is not appropriately<br />

dealt with in the country are evaluated through a recapturing of the historical<br />

evolution of the associated Brazilian institutional framework. Reydon concludes<br />

that adequate, participative and effective governance is a necessary, but<br />

insufficient, condition to contain deforestation in the region.<br />

Carlos Teodoro Irigaray analyzes the prospects and challenges of Brazilian<br />

law in the transition to a green economy. Irigaray starts by contextualizing<br />

green economy in the realms of sustainable development. The author argues<br />

that, from a legal perspective, the transition to a green economy requires<br />

measures that involve the structuring of a system that can effectively guide<br />

public policy, combining the use of economic instruments and command and<br />

control mechanisms, that, necessarily, should be informed by some ethical<br />

principles such as environmental justice and intra and intergenerational<br />

equity. In the context of Brazil, Irigaray identifies three main challenges to<br />

the transition: poverty, deforestation, and agriculture. The author asserts that<br />

Brazil already has a solid regulatory framework, and highlights the recognition<br />

of the fundamental right to an ecologically balanced environment associated<br />

with government and collectivity duty of defending and preserving this right.<br />

Nevertheless, some adjustments are necessary, such as institutionalizing<br />

REDD. Furthermore, the legislative advances are weakly reflected in practice.<br />

In this sense, contradictions between the policies of the Brazilian government<br />

are especially relevant.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Peter H. May brings up the issue of market mechanisms for a green economy.<br />

May claims that, from the perspective of ecological economics, instruments<br />

of natural resource management are based on two variables: the relative<br />

non-substitutability of the resource in question and its resilience (capacity to

14<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Executive Summary<br />

recover from stress or degradation). The author asserts, without ignoring the<br />

difficulty of precise their understanding, that these two variables reveal, without<br />

resorting to devices of market valuation, the biophysical constraints of human<br />

intervention. It is argued that command and control mechanisms can drive the<br />

direct regulation of resources, by establishing ceilings for levels of appropriate<br />

use (that could be null). Once caps are established, the market can act in a<br />

way to achieve efficient allocation (trade). The author specifically analyzes<br />

PES and REDD instruments. It is concluded that market mechanisms should<br />

assume an important role in the transition to a green economy, in a way that<br />

this role is mediated by regulation that defines the criteria of access and control<br />

of natural resources, reflected by biophysical limits backed by science and<br />

ample previous consultations with populations whose sustenance depends<br />

on those resources.<br />

Ronaldo Seroa da Motta presents the topic of valuation and pricing of<br />

environmental resources in a green economy. It is argued that, due to the lack<br />

of secure property and usage rights of natural resources, externalities are not<br />

totally captured by the price system, which consequently becomes imperfect and<br />

causes inefficient allocations of these resources. Seroa da Motta reveals the<br />

components of the Economic Value of Environmental Resources (EVER): the<br />

use value (direct use, indirect use, and option) and the non-use (or existence)<br />

value. Categories of environmental services are also presented (provision,<br />

regulation, support and cultural), and related to the EVER components. The<br />

author reveals the environmental economic evaluation methods, which can be<br />

grouped into production function methods and demand function methods, and<br />

presents the complexity that such exercises involve. Seroa da Motta analyses<br />

the possibilities of internalizing environmental externalities by charging or<br />

creating markets. The author concludes with an evaluation of the limits to the<br />

potential of valuation and economic pricing of the environment.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Mário Sérgio Vasconcelos analyzes the role of financial institutions in the<br />

transition to a green economy in Brazil. The author argues that starting in<br />

the 1990’s, a series of voluntary commitments and self-regulation has been<br />

implemented by the sector. He asserts that Brazil exhibits a distinguished<br />

performance among emerging countries. The author surveys the main<br />

pacts and commitments assumed by domestic banks. The Green Protocol<br />

is emphasized as an effort to adopt socio-environmental policies that are<br />

precursory, multiplicative, demonstrative or exemplary of banking practices<br />

and that are in line with the objective of promoting sustainable development.<br />

Vasconcelos presents some measures that Brazilian banks have taken to<br />

promote sustainability in the country. The author argues that these activities<br />

result from the fact that environmental risks have generated an actual and<br />

growing impact on the four large risks faced by banking institutions. The main

15<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Executive Summary<br />

challenges of the sector are also identified. It is concluded that banks no longer<br />

play the passive role of monitoring, but rather an active role of identifying<br />

entrepreneurs, technologies and new business models.<br />

Ultimately, Ronaldo Seroa da Motta and Carolina Dubeux conduct an analysis<br />

of the measurements of policies for the transition towards a green economy.<br />

The authors argue that it is possible to understand sustainability as that which<br />

allows us to maintain the capital stock, which defines the future fluxes of goods<br />

of services, at least constant. They defend that the capacities of ecosystems to<br />

generate services have limits, which, once surpassed, cause a collapse. The<br />

definition of these limits (that is, the critical level of natural capital) determines<br />

the sustainability trajectory of an economy. The green economy is that which<br />

produces a continuous increase in the stock of natural capital. The authors<br />

analyze the creation of institutional capacity to integrate environmental policies<br />

with economic policies and a system of environmental indicators that would be<br />

capable of measuring and monitoring the benefits of natural capital investments.<br />

They propose, in this sense, a systematization of environmental indicators, the<br />

amplification of economic instruments and the removal of perverse incentives.<br />

It is concluded that environmental regulation should not be seen as a problem<br />

and that, beyond a solution, it could represent a source of economic and social<br />

benefits for Brazil.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011

16<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Delineations of a green<br />

economy<br />

Helena Boniatti Pavese 1<br />

In t r o d u c t io n<br />

Over the past 50 years, human beings have been altering ecosystems at an<br />

increasingly accelerated and intensive pace than in any other period of human<br />

history, especially due to the increasing demand for natural resources, such as<br />

food, water, timber, fibers and fuels 2 .<br />

Despite the significant contribution to economic growth and to promoting<br />

social well-being, the excessive extraction of these resources led to irreversible<br />

losses of global biodiversity and services provided by ecosystems, many of<br />

which are considered essential to human survival.<br />

Wh a t a r e e n v ir o n m e n t a l s e r v i c e s?<br />

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Report (MEA) 3 ,<br />

environmental (or ecosystem) services are defined as “the benefits people<br />

obtain from ecosystems”.<br />

They can be divided into four categories:<br />

(i) provisioning services, such as food, water and timber, etc.;<br />

(ii) regulating services, such as those that affect climate, flooding,<br />

diseases, water quality, among others<br />

(iii) cultural services, related to recreational, esthetic and spiritual; and<br />

(iv) supporting services, which include soil formation, photosynthesis and<br />

nutrient recycling.<br />

Also according to the report, close to 60% of these services have been<br />

degraded or used unsustainably, including fresh water, purification of air and<br />

water, and local and regional climate regulation 4 . These alterations increase<br />

the probability of accelerated, abrupt and irreversible changes with significant<br />

consequences for human well-being, and threaten the survival of many<br />

communities, especially in developing countries, where in some cases close<br />

to 90% of GDP is linked to nature or natural resources 5 .<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

1. Environmental Policy Manager at Conservation International Brazil and former Regional<br />

Coordinator for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Conservation Monitoring<br />

Center of the United Nations Environment Programme (WCMC/UNEP).<br />

2. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005).<br />

3. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), p. V.<br />

4. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), p.1.<br />

5. UNEP (2011a).

17<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Delineations of a<br />

green economy<br />

Helena Pavese<br />

Despite the proven intrinsic relationship between human well-being and<br />

natural resources, unsustainable economic activities still prevail. Currently,<br />

around 1-2% of the global GDP are destined to substituting practices that, in<br />

many cases, lead to the degradation of natural resources, such as fishing and<br />

agriculture 6 .<br />

These investments are motivated by the rapid accumulation of physical,<br />

financial and human capital, disregarding natural capital, and thus generating<br />

a vicious cycle through which negative impacts exerted on natural resources<br />

consequently lead to negative impacts on human well-being and the escalation<br />

of poverty.<br />

This article aims to point out the main advances in the delineations of a<br />

green economy. Beyond this introduction, the article consists of three sections.<br />

The first elaborates on the Green Economy Initiative, and the output Report on<br />

green economy, launched in February 2011. The second presents some main<br />

results raised in this Report. Ultimately, are the final remarks.<br />

Th e Gr e e n Ec o n o m y Initiative<br />

Seeking to raise evidence about the social and economic risks and costs<br />

generated by current standards of excessive resource use as well as highlight<br />

opportunities for a transition to more sustainable practices, the United Nations<br />

Environment Programme (UNEP) launched the Green Economy Initiative (GEI)<br />

in 2008. The main objective of this initiative is to support the development of a<br />

global plan for the transition to a green economy that is dominated by investment<br />

and consumption of goods and services that promote the environment.<br />

Wh a t is a g r e e n e c o n o m y?<br />

Green economy is understood as “one that results in the improvement<br />

of human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing<br />

environmental risks and ecological scarcities”. 7<br />

A green economy is based on three main strategies: (1) the reduction<br />

of carbon emissions, (2) enhanced energy and resource efficiency and<br />

(3) the prevention of loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

To become viable, these strategies must be catalyzed and supported<br />

by targeted public and private investments as well as by political reforms<br />

and regulatory changes. Also, natural capital should be maintained,<br />

enhanced and, when necessary, rebuilt, especially for poor people whose<br />

livelihoods and security depend on nature.<br />

6. UNEP (2011a). p.1.<br />

7. How is a Green Economy Defined? (n.d.) Retrieved from: .

18<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Delineations of a<br />

green economy<br />

Helena Pavese<br />

The GEI flagship is the development of the Report about green economy,<br />

launched in February 2011, “Towards a green economy: pathways to sustainable<br />

development and poverty eradication”. The document contains an analysis<br />

of macroeconomic aspects and issues linked to sustainability and poverty<br />

reduction related to investments in a range of sectors from renewable energy<br />

to sustainable agriculture. It is expected that such analysis will support the<br />

formulation of policies that can catalyze an increase in investments in these<br />

green sectors. In addition to analyzing this content, GEI provides consulting<br />

services to countries and regions and produces research products as well<br />

as promotes the establishment of partnerships with a wide range of actors,<br />

including academia, non-governmental organizations, the private sector, among<br />

others, for the effective promotion and implementation of green economy<br />

strategies.<br />

“To w a r d s a g r e e n e c o n o m y: p a t h w a y s to<br />

s u s t a in a b l e d e v e l o p m e n t a n d p o v e r t y e r a d ic a t io n”<br />

Produced by the UNEP in partnership with global economists and specialists,<br />

the report “Towards a green economy: pathways to sustainable development<br />

and poverty eradication” seeks to defend the proposal that making economies<br />

green does not necessarily imply a reduction in economic growth and<br />

employment levels. On the contrary, such a transition would allow growth to<br />

be strengthened through the generation of descent jobs 8 and would consist<br />

of a vital strategy to eliminate poverty. It is hoped that the evidence raised by<br />

this study will encourage decision makers to develop favorable conditions for<br />

increased green economy investments, based on three main strategies:<br />

1. Stimulate a change in investments, both public and private, seeking to<br />

encourage critical sectors in the transition to a green economy;<br />

2. Demonstrate how a green economy can reduce persistent poverty through<br />

a wide range of important sectors, including agriculture, forestry, fishery, water<br />

and energy; and<br />

3. Provide guidelines on policies that permit this change; through the<br />

elimination of perverse subsidies, identification of market failures, establishment<br />

of regulatory frameworks or stimulus for sustainable investments.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

The report seeks to demystify the idea that there is an inevitable trade-off<br />

between social development, economic growth and environmental sustainability<br />

and dispel misconceptions that green economy is a luxury whose costs only<br />

developed countries can bear. The principal message highlighted by the Report<br />

is that:<br />

8. Employment that provide an adequate salary, social welfare and respect of workers’ rights<br />

that allow workers to express their opinions about decisions that affect their lives. Source: OIT<br />

(2009).

19<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Delineations of a<br />

green economy<br />

Helena Pavese<br />

“An investment equivalent to 2% of the global GDP in ten key sectors<br />

can combat poverty and generate greener and more efficient growth”.<br />

According to the Report, such an investment could be the initial kick-off for<br />

the transition to a green economy with efficient resource use and low carbon.<br />

The authors claim that this amount corresponds to only 1.3 trillion dollars per<br />

year and would drive global economic growth to levels that are probably higher<br />

than those of current economic models 9 .<br />

Agriculture, construction, fishery, forestry, energy supply, industry, tourism,<br />

transport, waste and water management are the 10 sectors evaluated in the<br />

study and identified as fundamental for making the global economy more<br />

green.<br />

For these sectors to transition to a greener economy, in general terms, the<br />

study puts forth the following allocation of resources 10 :<br />

• Agriculture: US$ 108 billion, includes small farms<br />

• Buildings: US$ 134 billion, applied to energy efficiency programs<br />

• Energy (supply): Above US$ 360 billion<br />

• Fisheries: US$ 110 billion, includes reducing the capacity of global fleets<br />

• Forestry: US$ 15 billion to combat climate change<br />

• Industry: US$ 75 billion<br />

• Tourism: US$ 135 billion<br />

• Transport: US$ 190 billion<br />

• Waste management: US$ 110 billion, includes recycling<br />

• Water: a similar amount, includes basic sanitation<br />

The report also presents results and recommendations for specific sectors,<br />

highlighting sectoral opportunities generated by the transition to a green<br />

economy, including poverty reduction, job creation, strengthened social equity<br />

and the maintenance and restoration of natural capital. Among these, the<br />

following stand out:<br />

Agriculture<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Reducing deforestation and increasing reforestation generate benefits<br />

for agriculture and rural communities, through the use of economic<br />

mechanisms and existing markets, such as, certifications for wood, payments for<br />

ecosystem services and potential benefits from REDD+ mechanisms, strategies<br />

that can currently be found in national and international discussion forums .<br />

9. UNEP (2011b), p.4.<br />

10. UNEP (2011a).

20<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Delineations of a<br />

green economy<br />

Helena Pavese<br />

Greener agriculture ensures food supply for a growing global population<br />

without harming the resource base of this sector. This can be done through<br />

the transition from industrial and subsistence agricultural practices to more<br />

sustainable models, with more efficient use of water, extensive use of organic<br />

or natural soil nutrients and integrated pest control 12 .<br />

The transition to a green economy also requires strengthened<br />

institutions and the development of infrastructure in rural areas of<br />

developing countries. This aspect includes the removal of ecologically<br />

perverse subsidies and the promotion of regulatory reform that incorporates<br />

the cost of degradation into food and commodity prices 13 .<br />

Greening agriculture in developing countries, concentrating on small<br />

properties, can reduce poverty while permitting investment in natural<br />

capital on which the poorest depend. The adoption of sustainable practices<br />

(such as agroforestry, integrated management of nutrients and pests) is one of<br />

the most efficient ways to increase the availability of food and facilitate access<br />

to emerging international markets for green products. Adopting such practices<br />

can move agriculture from the position as major greenhouse gas emitter to a<br />

neutral position, and also contribute to reducing deforestation and water use<br />

by 55% and 35%, respectively 14 .<br />

Water<br />

The growing scarcity of water can be mitigated through fomentation<br />

policies and investments aimed at improving the provision and efficiency<br />

of water use 15 .<br />

Investments in the provision of drinking water and sanitation services<br />

for the poor represent a great opportunity to accelerate the transition to<br />

a green economy in many developing countries. Annual investments of<br />

0.15% of the global GDP would enable global water use to be maintained at<br />

sustainable levels as well as the achievement of the Millennium Development<br />

Goals related to water by 2015 16 .<br />

The supply of jobs in the water sector would suffer temporary<br />

adjustments due to the necessity of recovering water resources.<br />

Improvements in efficiency and reductions in consumption would reduce<br />

total water consumption by 20% and employment opportunities by 25% by<br />

2050 compared to current rates. However, such forecasts do not capture new<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

11. UNEP (2011b), p.6.<br />

12. UNEP (2011b). p.7.<br />

13. UNEP (2011b). p.7.<br />

14. UNEP (2011b). p.9.<br />

15. UNEP (2011b). p.8.<br />

16. UNEP (2011b). p.10.

21<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Delineations of a<br />

green economy<br />

Helena Pavese<br />

job opportunities generated by infrastructure developments aimed at water<br />

efficiency 17 .<br />

Energy sector<br />

Renewable energy presents great economic opportunities. “Greening”<br />

the energy sector requires a substitution of investments in carbon intensive<br />

energy sources to investments in clean energy, as well as improvements in<br />

energy efficiency. Many of these investments would be rewarded in the future,<br />

considering the growth in the market for renewable technologies and the<br />

growing concern over the social costs generated by technologies based on<br />

fossil fuels 18 .<br />

Government policies play an essential role in strengthening incentives<br />

for investments in renewable energy, including time-bound incentives, feedin<br />

tariffs (payments for renewable energy that users produce), direct subsidies<br />

and tax credits 19 .<br />

A minimum allocation of 1% of the global GDP to increase energy<br />

efficiency and expand the use of renewable energy would create additional<br />

jobs and produce more competitive energy 20 .<br />

An annual investment of around 1.25% of the global GDP in energy<br />

efficiency and renewable energy could reduce global primary energy<br />

demands by 9% by 2020 and 40% by 2050 21 .<br />

Tourism<br />

The development of tourism, when well designed, can strengthen local<br />

economies and reduce poverty 22 .<br />

Fisheries<br />

Investments in the fisheries management, including the creation of<br />

protected marine areas, and deactivation and reduction in fleet capacity<br />

can recuperate the fishery resources of the planet. Such recuperation entails<br />

an increase in catches from the current 80 million tons to 90 million as well as<br />

the creation of a significant number of jobs in the sector by 2050 23 .<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

17. UNEP (2011b). p.13.<br />

18. UNEP (2011b), p.14.<br />

19. UNEP (2011b), p.15.<br />

20. UNEP (2011b), p.12.<br />

21. UNEP (2011a).<br />

22. UNEP (2011b), p.11.<br />

23. UNEP (2011a).

22<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

The benefits from a transition of the fishing industry exceed 3 to 5 times<br />

the investment necessary for this transition 24 .<br />

The job supply in the fishery sector would suffer temporary adjustments<br />

due to the necessity of recovering fish stocks. “Greening” the fisheries<br />

sector would result in job losses in the short and medium terms, but the long<br />

term supply would go back up due to the recuperation of fish stocks 25 .<br />

Delineations of a<br />

green economy<br />

Helena Pavese<br />

Waste management<br />

With a 108 billion dollar annual investment in “greening” the waste sector,<br />

the global recycling of waste could triple by 2050. This would imply a reduction<br />

of more than 85% of the amounts currently deposited in landfills 26 .<br />

Such investments may result in full recycling of electronic wastes, as<br />

compared to current levels of 15% 27 .<br />

A 10% increase in the life-spans of all products produced would lead<br />

to a similar reduction in the volume of extracted resources.<br />

The job supply in the waste management sector would grow as a result<br />

of the increased waste generated by population and income growth, but<br />

the challenges related to the generation of descent employment in this<br />

sector are considerable. Currently, recycling generates around 12 million<br />

jobs in only three countries (Brazil, China and the United States) 28 . In green<br />

investment scenarios, projected growth of the job supply in the waste sector<br />

would be 10% compared to current trends.<br />

Transport<br />

Annual investments of 0.34% of the global GDP up to 2050 could reduce<br />

the use of petroleum by 80%, compared to current patterns, and elevate<br />

employment rates by 6% 29 .<br />

The environmental and social costs generated by the transport sector<br />

are currently at around 10% of the GDP of a country or region.<br />

A “greening” of the transport sector requires the creation of policies to<br />

foster the utilization of public and non-motorized transport, fuel efficiency<br />

and the development of less polluting vehicles.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

24. UNEP (2011b), p.11.<br />

25. UNEP (2011b), p.13.<br />

26. UNEP (2011a).<br />

27. UNEP (2011a), p.1.<br />

28. UNEP/ILO/IOE/ITUC (2008).<br />

29. UNEP (2011b), p.23.

23<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

Delineations of a<br />

green economy<br />

Helena Pavese<br />

Gr e e n e c o n o m y: p o s s i b l e a n d d e s ir a b l e<br />

The final message transmitted by the report is that a green economy is both<br />

desirable and possible. This concept possesses the potential to promote the<br />

much desired sustainable development and poverty eradication, rapidly and<br />

effectively. A green economy favors growth with the generation of income and<br />

jobs.<br />

However, such a transformation is subject to two great changes: in the way<br />

our economy is structured and in the recognition that the environment forms the<br />

basis of our physical goods, which should be managed as sources of growth,<br />

prosperity and well-being 30 .<br />

Green investments have great potential to strengthen sectors and technologies<br />

that could be the main promoters of economic and social development in the<br />

future, including technologies for renewable energy, energy efficient construction<br />

and low-carbon transport systems 31 .<br />

Thus, in addition to technologies, complimentary investments in human capital<br />

would also be necessary, which includes generating and sharing strategies,<br />

mechanisms and policies that promote a transition to a green economy 32 .<br />

Therefore, the transition to a green economy triggers, according to the<br />

Report, a series of desirable results in the long term, whether in economic,<br />

social or environmental terms. The Report offers clear directives of what can<br />

be done in each of the ten sectors analyzed to bring about such a transition.<br />

The document supports the proposition that a transition to a green economy<br />

would bring benefits in the long term that would compensate for possible short<br />

term losses.<br />

References<br />

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being:<br />

Synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press, p.1.<br />

OIT (2009). Programa Empregos Verdes. Brasília: OIT.<br />

UNEP (2011a). Rumo a uma economia verde: caminhos para o desenvolvimento<br />

sustentável e a erradicação da pobreza, Press Release United Nations Environment<br />

Programme. Retrieved from: .<br />

UNEP (2011b). Towards a Green Economy: pathways to sustainable development and<br />

poverty eradication. United Nations Environment Programme, p.4.<br />

UNEP/ILO/IOE/ITUC (2008). Green jobs: towards decent work in a sustainable, lowcarbon<br />

world. Nairobi: UNEP.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

30. UNEP (2011b), p. 37.<br />

31. UNEP (2011b), p. 37.<br />

32. UNEP (2011b), p. 37.

24<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

The necessarily systemic<br />

character of the transition<br />

to a green economy<br />

Alexandre d´Avignon 1<br />

Luiz Antônio Cruz Caruso 2<br />

The green economy as defined in the United Nations Environment<br />

Programme’s (UNEP) publication, “Towards a green economy: pathways to<br />

sustainable development and poverty eradication”, brings a series of challenges.<br />

This economy seeks human well-being and social equity, while reducing<br />

environmental risks and resource scarcity, and is characterized by low carbon<br />

intensity. Certainly this was not the first expression that captures the aspirations<br />

of those who seek structural changes in the capitalist economy, focused on<br />

values other than the maximization of profits, in a perfectly competitive market<br />

tending to equilibrium. The breakthrough of this approach is essentially in its<br />

overcoming the anthropocentric view of nature and the planet, in which these<br />

must serve humankind and attend its needs. As René Passet (1991) pointed,<br />

the order and the cycles of nature must be respected so as not to exhaust its<br />

potentialities and energy sources.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

The biosphere and the interactions of its subsystems (atmosphere,<br />

lithosphere, hydrosphere and biota) determine the conditions under which<br />

human activities can take place, whether social or economic. Ultimately, it is<br />

the biosphere that will determine the limits and possibilities of mutual influence<br />

between living beings and the planet. Humans are part of this whole, and an<br />

important part because of their ability to intervene in the environment, but there<br />

is not a hierarchy in which humans are at the top. The relationship between<br />

human societies and the biosphere cannot be reduced to economic or even<br />

social dimensions. Human activities such as are analyzed in economics through<br />

the relations of production, exchange, consumption, etc. represent only a first<br />

sphere of human practices in an ordainment with specific rules established,<br />

included in a broader social sphere, civil society, the state, ideologies etc. Yet<br />

the latter is circumscribed, in turn, by an even broader universe consisting of<br />

inanimate and living matter, which surrounds and extends beyond. It is within<br />

these three spheres – modes of production, formation of society and the<br />

1. Professor of the Program for Public Policies, Strategies and Development of the Economics<br />

Institute of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (PPED/IE/UFRJ) and researcher at the<br />

Program for Energy Planning (COPPE/UFRJ).<br />

2. Doctoral student at the Program for Public Policies, Estrategies and Development of the<br />

Economics Institute of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (PPED/IE/UFRJ).

25<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

The necessarily<br />

systemic character<br />

of the transition to a<br />

green economy<br />

Alexandre d'Avignon<br />

Luiz Caruso<br />

biosphere – that human activities are inserted. The reproduction and functioning<br />

of each sphere are regulated by the other two. Due to the relationship between<br />

these three spheres of inclusion, it can be affirmed that the elements of the<br />

economic sphere belong to the biosphere and obey its laws, but that all elements<br />

of the biosphere do not belong necessarily pertain to the economic sphere of<br />

economy and are not subject to its rules. As James Lovelock (2001) states, the<br />

earth became what it is through its habitation by living beings and these have<br />

been the means but not the purpose for the planet’s development.<br />

It is interesting to observe, however, that at UNEP’s homepage on the internet,<br />

where the above publication can be accessed, is a statement in small print:<br />

“environment for development.” Is this not a contradiction of the perception<br />

of the program regarding the proposed definition of green economy in the<br />

publication?<br />

Painting neoclassical economics green is not the solution. We need a<br />

structural change in the “household management” (oikos = house + nomia =<br />

management, study or laws, according to Houaiss, 2001), referring to the planet<br />

as the home of all living beings and, as such, needing to be preserved and<br />

respected. Making the conventional economy green, from UNEP’s perspective,<br />

is to prioritize growth of income and employment. The latter are to be stimulated<br />

by public and private investments that reduce carbon emissions and pollution<br />

and promote the efficient use of energy and natural resources, preventing the<br />

loss of ecosystem services and biodiversity. These investments will be catalyzed<br />

and supported by public policy reforms and regulatory changes. The proposed<br />

route of development should maintain, enhance and, where necessary, restore<br />

natural capital, since it is a critical economic asset that generates public benefits,<br />

especially for poor people whose livelihoods and security depend essentially<br />

on nature.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

Encouraging public and private entities to assume primary responsibility,<br />

in which the action of external private or public agents is proposed as the<br />

solution, is precisely the approach criticized by Elinor Ostrom (2008). According<br />

to her, this option comes from a metaphorical and specific view contained in<br />

the “Tragedy of the Commons”, described by Garrett Hardin in 1968, and the<br />

Prisoner’s Dilemma model proposed by the same author, as well as the “Logic<br />

of Collective Action” developed by Mancur Olson with the idea of free riding in<br />

joint activities in a community for the public good. Ostrom questions currently<br />

fashionable approaches involving intervention by coercive or regulatory state<br />

action or by the definition of ownership through privatization. Empirically, such<br />

approaches are associated with a huge list of failures. In Ostrom’s view, solutions<br />

should always be defined on a case-by-case basis through agreement among<br />

stakeholders, for managing what she calls the use of common resources, i.e.,<br />

public goods. The author describes a number of real alternative solutions to<br />

external intervention.

26<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

The necessarily<br />

systemic character<br />

of the transition to a<br />

green economy<br />

Alexandre d'Avignon<br />

Luiz Caruso<br />

In the UNEP publication, biodiversity, as an example of a public good,<br />

would not be valued properly in neoclassical economics. Nor can neoclassical<br />

economics properly value environmental services, which contribute to human<br />

welfare and family livelihoods and could provide a source of new skilled<br />

jobs. Estimating the economic value of ecosystem services is essential for<br />

the identification of natural capital. This is one of the dimensions that would<br />

support the transition to a green economy, stimulating a change in conventional<br />

economic indicators and leading them to account for the loss of natural capital<br />

as negative and not positive components of national accounts. Is the correct<br />

valuation of these services associated with favorable conditions sufficient<br />

conditions for this transition?<br />

How can one assign new parameters to a green economy, if the essential<br />

discussion of equity and local participation is kept on the sidelines? The<br />

voracious consumption of energy and natural resources characteristic of<br />

industrialized countries shows that this is not a development model that<br />

respects the biosphere, its principles and pace of regeneration. The legacy left<br />

by development based on fossil fuels has brought to the forefront global issues<br />

such as climate change and ozone layer destruction, revealing economic options<br />

that were imposed, causing the abandonment of innovations that could have<br />

been stimulated by national innovation systems, which would involve R&D,<br />

legal framework of incentives and patent system. An important example would<br />

be the intensive use of biomass through the BTL (Biomass to Liquid) or BTG<br />

(Biomass to Gas) at a growth rate appropriate to the regenerative capacity of<br />

natural resources. Energy from solar and photovoltaic sources, wind power,<br />

hydrogen, more efficient batteries were not adequately exploited due to current<br />

technological route, causing the abandonment in the past of other options.<br />

It is worth recalling that Rudolf Diesel patented his engine to work with<br />

vegetable oils, in this case of peanuts, and even before his presentation at<br />

the Paris World Fair in 1898, there were manufactures of vehicles with electric<br />

motors. The latter have proliferated in public transport with trams, which were<br />

later replaced by internal combustion vehicles in several cities. If there had not<br />

been an imposition by specific economic sectors, these technologies could<br />

have persisted and received a share of investments from national innovation<br />

systems. In this case, the options nowadays in terms of development of<br />

technologies considered as alternatives would have been much more promising,<br />

comprehensive and widespread.<br />

Nº 8 • June 2011<br />

This short historical account raises other issues related to the green economy.<br />

Could the problems generated by the economy practiced today be overcome by<br />

adopting the recommendations proposed by UNEP, during the next 20 years,<br />

as indicated by the scenario options displayed in “Towards a Green Economy:<br />

Pathways to Sustainable Development and Eradication Poverty”? Shouldn’t

27<br />

GREEN ECONOMY<br />

Challenges and<br />

opportunities<br />

The necessarily<br />

systemic character<br />

of the transition to a<br />

green economy<br />

Alexandre d'Avignon<br />

Luiz Caruso<br />

the economic model proposed have been adopted years ago due to the global<br />

issues we face today such as global warming? Isn’t it now too late?<br />

In addition to the balanced access to natural and energy resources by the<br />

planet’s population, there is a need for the development of technologies based<br />

on regional vocations and not the imposition of a technological pathway derived<br />

from economies of scale and short-term profits. The technologies relating to<br />

the burning of liquid or solid fossil fuels in thermodynamic cycles generally<br />

capable of using no more than 30% of energy supplied, rather than more<br />

elegant alternatives, such as the manufacture of polymers, is an example of<br />

the imposition of a single pathway, dominated by large global organizations.<br />

Cogeneration of power and fixed systems integrated to generate electricity<br />

and heat, for example, are much more efficient and would provide yields up to<br />

50% in automobile engines.<br />

Temporal equity is another important element to be taken into account, since<br />

it brings us to the origin of the concept of sustainable development contained<br />

in “Our Common Future”, a publication resulting from the 1987 Brundtland<br />

Report. This book provides as one definition of the concept: “Development that<br />

seeks to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the<br />

ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This means enabling<br />