Country Economic Work for Malaysia - Islamic Development Bank

Country Economic Work for Malaysia - Islamic Development Bank

Country Economic Work for Malaysia - Islamic Development Bank

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Acknowledgements<br />

Appreciation <strong>for</strong> special contribution<br />

Tan Sri Dr Wan Aziz Wan Abdullah, Dato’ Dr. Mohd Irwan Serigar bin Abdullah, Mr. Maliami Hamad, and Mr.<br />

Jaya Kumaran Vengadala, Ministry of Finance, Government of <strong>Malaysia</strong>; Datuk Dr. Abd Shukor Abd Rahman,<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong>n Agriculture Research and <strong>Development</strong> Institute; Mr. Lt Col Prof Dato’ Husin Bin Jazri, Cybersecurity;<br />

Mr. Ahmad Zam Zam Mohamed, Marditech; Mr. Amilin Yusman Yusoff, Maybank; Mr. Anas Ahmad Nasarudin,<br />

Marditech; Mr. Daud David Vicary, INCEIF; Dr. Mazliham Mohd Su'ud, UniKL; Ms. Mazidah Malik, <strong>Bank</strong><br />

Negara <strong>Malaysia</strong>; Mr. Rafaiq Bakri bin Zakaria, Suruhanjaya Tenaga; and Ms. Sharifah Noor Ashikin Syed Aznal,<br />

Rafulin Holdings.<br />

IDB Group Team<br />

<strong>Country</strong> Programs Department and ROKL<br />

Mr. Mohammad Jamal Al-Saati, Director; Mr. Kunrat Wirasubrata, Office-In-Charge ROKL; Mr. Mohammad<br />

Nassis Sulaiman, <strong>Country</strong> Manager; Mr. Abdallah M. Kiliaki (Peer Reviewer); Dr. Nosratollah Nafar (Peer<br />

Reviewer); Mr. Mohammad Takyuddin Yahya and ROKL Staff.<br />

Overall Coordinator<br />

Mr. Ahmed Hariri, Regional Manager, South & South East Asia Region and Surinam<br />

Report Authors & Contributors<br />

Dr. Zafar Iqbal, Lead Economist, <strong>Country</strong> Programs Department<br />

Mr. Saifullah Abid, <strong>Country</strong> Manager <strong>for</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Mr. Hammad Zafar Hundal, <strong>Country</strong> Manager<br />

Special Thanks to Dr. Mohammad Ahmed Zubair, Principal Economist, <strong>Country</strong> Programs<br />

Department; Dr. Intizar Hussain, Division Manager; Mr. Aamir Ghani Mir, Database Management<br />

Expert; and Mr. Waleed Ahmad Addas, Lead Operations Officer, Operations Policy and Services<br />

Department (OPSD) <strong>for</strong> their valuable comments and improving the quality of the document.<br />

Team-I<br />

Reverse Linkages<br />

Mr. Zishan Iqbal, Team Leader<br />

<strong>Islamic</strong> Financial Services Department<br />

Mr. Haseebullah Siddiqui<br />

Human <strong>Development</strong> Department<br />

Mr. Aminuddin Bin Mat Ariff<br />

<strong>Islamic</strong> Research and Training Institute<br />

Dr. Nasim Shah Shirazi<br />

Treasury Department<br />

Mr. Zainol bin Mohamud<br />

Mr. Zakky Bantan<br />

<strong>Economic</strong> Research and Policy Department<br />

Dr. Muhamed Zulkhibri<br />

Team-II<br />

Private Sector <strong>Development</strong><br />

Mr. Irfan Bukhari, Team Leader<br />

<strong>Islamic</strong> Corporation <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Development</strong><br />

of the Private Sector (ICD)<br />

Mr. Ahmed bin Abdul Khalid<br />

Dr. Elvin Afandi<br />

<strong>Islamic</strong> Corporation <strong>for</strong> the Insurance of<br />

Investment and Export Credit (ICIEC)<br />

Mr. Zishan Iqbal<br />

International <strong>Islamic</strong> Trade Finance<br />

Corporation (ITFC)<br />

Mr. Abdul Aleem Habib<br />

Mr. Amir Asad Hedayati<br />

Infrastructure Department (PPP)<br />

Mr. Irfan Bukhari<br />

Group Risk Management Department<br />

Mr. Ahmed Murad Hammouda<br />

Mr. Husam AlAkhal<br />

External Consultants: Dr. Tengku Mohd Azzman Shariffadeen and Mr. Rizal Kamaruzzaman,<br />

Tindakan Strategi (Empowering Strategic Decisions) SDN BHD.

Abbreviations and Acronyms<br />

ADB : Asian <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Bank</strong><br />

AIM : Agensi Inovasi <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

APIF : Awqaf Properties Investment Fund<br />

ASEAN : Association of Southeast Asian Nations<br />

BAP : Business Accelerator Programme<br />

BNM : <strong>Bank</strong> Negara <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

CEW : <strong>Country</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Work</strong><br />

CGC : Credit Guarantee Corporation<br />

CIS : Commonwealth of Independent States<br />

CMSA : Capital Market Services Act<br />

E² : Enrichment & Enhancement Programme<br />

ECER : East Coast <strong>Economic</strong> Region<br />

EIU : <strong>Economic</strong> Intelligence Unit<br />

EPP : Entry Point Projects<br />

ETP : <strong>Economic</strong> Trans<strong>for</strong>mation Program<br />

EU : European Union<br />

FASAS : Federation of Asian Scientific Academies and Societies<br />

FDI : Foreign Direct Investment<br />

GDP : Gross Domestic Product<br />

GHP : Good Hygiene Practices<br />

GOM : Government of <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

GLC : Government Linked Companies<br />

GTP : Government Trans<strong>for</strong>mation Programme<br />

HDC : Halal Industries <strong>Development</strong> Corporation<br />

HDI : Human <strong>Development</strong> Index<br />

HIPs : High Impact Programmes<br />

IAS : <strong>Islamic</strong> World Academy of Sciences<br />

IBFIM : <strong>Islamic</strong> <strong>Bank</strong>ing and Finance Institute <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

ICD : <strong>Islamic</strong> Corporation <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Development</strong> of the Private Sector<br />

ICIEC : <strong>Islamic</strong> Corporation <strong>for</strong> Insurance of Investment and Export Credit<br />

ICSU : International Council <strong>for</strong> Science<br />

IDB : <strong>Islamic</strong> <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Bank</strong><br />

IDB Group : IDB, ICIEC, IRTI, ICD, ITFC<br />

IDB-MDP : IDB Microfinance <strong>Development</strong> Programme<br />

ICBU : International Currency Business<br />

ICM : <strong>Islamic</strong> Capital Market<br />

ICT : In<strong>for</strong>mation and Communication Technologies<br />

IFAD : International Fund <strong>for</strong> Agricultural <strong>Development</strong><br />

IFSB : <strong>Islamic</strong> Financial Services Board<br />

IMF : International Monetary Fund<br />

INCEIF : International Centre <strong>for</strong> Education in <strong>Islamic</strong> Finance<br />

IRDA : Iskandar Regional <strong>Development</strong> Authority<br />

IRTI : <strong>Islamic</strong> Research and Training Institute

ISRA : International Shari’ah Research Academy <strong>for</strong> <strong>Islamic</strong> Finance<br />

ISTIC : International Science Technology and Innovation Centre <strong>for</strong> South<br />

South Cooperation<br />

ITAP : Investment Technical Assistance Program<br />

ITFC : International <strong>Islamic</strong> Trade Finance Corporation<br />

KEI : Knowledge Economy Index<br />

KLIFD : The Kuala Lumpur International Financial District<br />

MARDI : <strong>Malaysia</strong> Agriculture Research and <strong>Development</strong> Institute<br />

MATRADE : <strong>Malaysia</strong>n External Trade <strong>Development</strong> Corporation<br />

MC : Member <strong>Country</strong><br />

MCPS : Member <strong>Country</strong> Partnership Strategy<br />

MDBs : Multilateral <strong>Development</strong> <strong>Bank</strong>s<br />

MDGs : Millennium <strong>Development</strong> Goals<br />

MIDA : <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Investment <strong>Development</strong> Authority<br />

MIGHT : <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Industry-Government Group <strong>for</strong> High Technology<br />

MIFC : <strong>Malaysia</strong> International <strong>Islamic</strong> Financial Centre<br />

MNCs : <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Multinational Companies<br />

MTCP : <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Technical Corporation Programme<br />

MTN : Medium Term Note<br />

NEM : New <strong>Economic</strong> Model<br />

NCER : Northern Corridor <strong>Economic</strong> Region<br />

NCIA : Northern Corridor Implementation Authority<br />

NKEA : National Key <strong>Economic</strong> Areas<br />

ODI : Overseas <strong>Development</strong> Institute<br />

OEM : Original Equipment Manufacturing<br />

OIC : Organization of <strong>Islamic</strong> Conference<br />

OIC-CERT : OIC-Computer Emergency Response Team<br />

PFI : Private Finance Initiative<br />

PIA : Promotion of Investment Act<br />

PPP : Public Private Partnership<br />

RBF : Results Based Framework<br />

RENTAS : Real-time Electronic Transfer of Funds and Securities<br />

REITs : <strong>Islamic</strong> Real Estate Investment Trusts<br />

ROKL : Regional Office Kuala Lumpur<br />

R & D : Research and <strong>Development</strong><br />

SAC : Shariah Advisory Council<br />

SARS : Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome<br />

SCORE : Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy<br />

SDC : Sabah <strong>Development</strong> Corridor<br />

SEZ : Special <strong>Economic</strong> Zones<br />

SEAP : SME Expert Advisory Panel<br />

SIP : SME Investment Programme<br />

SMEs : Small and Medium Size Enterprises<br />

SRI : Strategic Re<strong>for</strong>m Initiatives<br />

TWAS : Academy of Sciences <strong>for</strong> the Developing World<br />

UNCTAD : United Nations Conference on Trade and <strong>Development</strong>

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………….. 1<br />

I. DIAGNOSTING THE MALAYSIAN ECONOMIC: SOCIO-ECONOMIC<br />

DEVELOPMENT…………………………………………................................. 5<br />

II. RECENT SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT………..….…………...... 5<br />

III. MAJOR ISSUES/ CHALLENGES FACING THE COUNTRY …………… 10<br />

IV. DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS OF BINDING CONSTRAINTS TO<br />

SUSTAINABLE ECONOMIC GROWTH…………….……..……..……....... 12<br />

i. Growth Diagnostic Framework………………………………………… 13<br />

ii. Constraints to Private Investment……………………………………… 15<br />

iii. Constraints to Public Investment……..……………………….……….. 23<br />

iv. Constraints to Software of <strong>Economic</strong> Growth………………………… 25<br />

v. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………….. 30<br />

V. DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS OF PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT IN<br />

MALAYSIA ……………………………………………………………............. 33<br />

i. <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s New <strong>Economic</strong> Model: Private Sector as Primary Growth<br />

Engine…………………………………………………………………….. 34<br />

ii. Binding Constraint to Private Sector <strong>Development</strong> …….…………….. 37<br />

iii. Diagnostic Analysis at Sub-Sector Levels……………………………… 39<br />

(i) Public Private Partnerships………………………………………... 39<br />

(ii) Innovation………………………………………………………........ 44<br />

(iii) SMEs <strong>Development</strong>…………………………………………………. 46<br />

(iv) Private Sector Resource Mobilization…………………………….. 48

(v) Foreign Direct Investment…………………………………………. 52<br />

iv. Conclusion………………………………………………………………... 54<br />

VI. DIAGNOSING THE POTENTIAL OF REVERSE LINKAGES<br />

OPPORTUNITIES IN MALAYSIA ………………………………….............. 55<br />

i. Reverse Linkages: Tool <strong>for</strong> Promoting South South Cooperation…… 55<br />

ii. Reverse Linkages Opportunities in <strong>Malaysia</strong>. ….……………………... 55<br />

(i) Benefitting from <strong>Islamic</strong> Financial System Strengths …………... 56<br />

(ii) Collaboration with <strong>Malaysia</strong> Science Academy………………….. 62<br />

(iii) Sharing SMEs <strong>Development</strong> Experience…………………………. 65<br />

(iv) Promoting Halal Industry…………….…………………………… 67<br />

(v) Enhancing Innovation Exchange…………………..……………… 72<br />

(vi) Getting Benefit from Trade and EXIM Activities……….………. 73<br />

(vii) Benefitting through <strong>Malaysia</strong> Technical Cooperation Program.. 75<br />

(viii) Sharing In<strong>for</strong>mation and Communication Technology................ 80<br />

iii. Conclusion………………………………………………………………... 82

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

The main objective of this <strong>Country</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Work</strong> (CEW) is to provide analytical basis <strong>for</strong><br />

designing IDB Group Member <strong>Country</strong> Partnership Strategy (MCPS) <strong>for</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong>. This CEW is<br />

prepared by the IDB Group MCPS Team based on available in<strong>for</strong>mation and data from reliable<br />

national and international sources; two background studies prepared by the local Consultants;<br />

bilateral meetings with the key stakeholders; and outcome of two Consultative <strong>Work</strong>shops<br />

(attended by the public sector, private sector, academia, civil society etc.) held in <strong>Malaysia</strong>.<br />

The growth story that has trans<strong>for</strong>med <strong>Malaysia</strong> to be an upper-middle income country can be<br />

divided into two main phases: First phase, high economic growth during 1967-1997 when<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> (as one of 13 countries in the world) sustained growth of more than 7% per annum. The<br />

main driver of economic growth was surging domestic private investment rate at 26.9% of GDP<br />

accompanied by supportive public investment rate of 12.4% of GDP during 1990-1997 1 . Second<br />

phase: (post-Asian financial crisis) relatively slow economic growth during 2000-2011 of<br />

average 5% per annum was mainly due to perceptible drop in domestic private investment rate at<br />

10.5% of GDP per annum while public investment per<strong>for</strong>med countercyclical role to partly offset<br />

the slowdown in private investment. In terms of sectoral per<strong>for</strong>mance, the services sector<br />

remained the main source of economic growth. In 2009, the manufacturing sector was hit hard<br />

with negative growth of 9.3% on account of global recession but recovered remarkably with a<br />

positive growth of 11.4% in 2010. Compared to other key sectors, growth in the agriculture sector<br />

remained relatively slow. During 2000s, the agriculture sector grew by 3.2% per annum.<br />

Other macroeconomic indicators also showed sound per<strong>for</strong>mance of the economy. For example,<br />

the average current account surplus remained 12.8% of GDP and trade surplus 16.9% of GDP per<br />

annum during 2000-2011, significantly high compared to other competitive countries in the Asian<br />

region. Inflation remained at the modest level (average 2.2% per annum during 2000-2011).<br />

<strong>Bank</strong>ing sector is built on solid foundations, with strong capital adequacy and a considerable<br />

amount of excess liquidity (surplus liquidity of MYR255 billion or $82.6 billion in 2011).<br />

However, federal budget deficit remained average 5% of GDP during 2000-2011 but currently<br />

fiscal consolidation is underway.<br />

In addition to the remarkable progress in macroeconomic indicators, <strong>Malaysia</strong> has steadily<br />

improved its human development indicators and has been considered as a high human<br />

development country (HDI ranking 61 out of 169 countries in 2011). The country has also made<br />

remarkable achievement in reducing poverty (from 49.3% in 1970 to 3.8% in 2009), and the<br />

economy remains almost at full employment level (i.e. unemployment rate 3.1% in 2011).<br />

Using a comprehensive Growth Diagnostic Framework, which was developed by the MCPS<br />

Team (an extended version of Growth Diagnostic Framework of Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco<br />

1 <strong>Malaysia</strong>n National Accounts and the World <strong>Bank</strong>, World <strong>Development</strong> Indicators do not provide data on private<br />

investment prior to 1990.<br />

1

(2005)), key insights emerged in two areas; namely, Private Sector <strong>Development</strong> and Reverse<br />

Linkages Opportunities (also main pillars chosen <strong>for</strong> the MCPS <strong>for</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong> <strong>for</strong> 2012-2015). The<br />

diagnostic analysis identifies the following binding constraints to economic growth in <strong>Malaysia</strong>:<br />

(i)<br />

(ii)<br />

Low Level of Private Investment: Prior to the Asian financial crisis, private investment<br />

was at the maximum level of 32% of GDP in 1997, which considerably declined to<br />

10.3% of GDP in 2010 and FDI declined from 6.3% of GDP during 1990s to 2.9% of<br />

GDP during 2000s. Current total investment rate (both public and private investment) in<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> (i.e. 20.3% of GDP) is less than the benchmark investment rate of 25% of GDP<br />

<strong>for</strong> achieving high and sustainable real GDP growth, according to World <strong>Bank</strong><br />

Commission’s Report on Growth and <strong>Development</strong> (2008). The local and <strong>for</strong>eign private<br />

investments have been constrained mainly due to low level of returns on investments, and<br />

some bureaucratic issues. In particular, investors’ major concerns are related to starting a<br />

business, obtaining construction/ business permits, registering property, and getting<br />

credit.<br />

Low Level of Public Investment: Public investment declined from the peak level of<br />

15.4% of GDP in 2002 to 10% of GDP in 2010, which is attributed to budgetary<br />

limitations (average budget deficit 5% of GDP during 2000-2011). This is also attributed<br />

to the Government’s policies towards supporting and encouraging private sector<br />

investment, particularly the infrastructure. The 7% sustained real GDP growth in<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> achieved during 1967-1997 was not only due to high level of private investment<br />

but also attributed to strong public investment, which could not be sustained thereafter.<br />

(iii) Weak Software of Growth: <strong>Malaysia</strong>n global competitiveness ranking slipped from 19<br />

in 2006 to 26 in 2010 (out of 142 countries); however, it has improved to 21 in 2011.<br />

Comparing with other competing countries in the region, <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s international<br />

competitiveness is weak due to low quality of higher education, skills and training, weak<br />

technological readiness, low spending on R&D, slow innovation, and low labor<br />

productivity. These findings are consistent with the World <strong>Bank</strong> (2010) Composite Index<br />

of Constraint, which ranked <strong>Malaysia</strong> 2 <strong>for</strong> skill development and 3 <strong>for</strong> entrepreneurial<br />

development (0 <strong>for</strong> severe binding constraint and 10 <strong>for</strong> least severe binding constraint).<br />

(iv)<br />

Similar to private investment, relevant stakeholders in the country identified the<br />

following binding constraints <strong>for</strong> overall Private Sector <strong>Development</strong>:<br />

‣ Inadequately educated work<strong>for</strong>ce<br />

‣ Difficulties in dealing with tax administration and getting business licenses and<br />

permits<br />

‣ Difficulty to locate and recruit the needed skills<br />

‣ In terms of higher education and training, and technological readiness, the<br />

challenges remain even more substantial<br />

‣ Evidence suggests that weak innovation is hindering the private sector<br />

development in the country<br />

2

(v)<br />

(vi)<br />

(vii)<br />

(viii)<br />

‣ Weak innovation and business sophistication are due to low budget <strong>for</strong> research<br />

and development (R&D)<br />

Binding Constraints Facing the PPPs: They include inadequate availability and<br />

accessibility to long-term financing; and land acquisition issues/disputes settlement<br />

particularly <strong>for</strong> road projects.<br />

Critical Constraints Facing the SMEs: They include insufficient access to funding<br />

sources; weak access to markets; poor ability to absorb and retain good talent in the<br />

industry; and insufficient availability of skilled work<strong>for</strong>ce.<br />

Binding Constraints <strong>for</strong> Private Sector Resource Mobilization: They include limited<br />

products offered by <strong>Islamic</strong> banking industry; narrow international base of <strong>Islamic</strong> capital<br />

market; lack of innovation; and shortage of skilled and experienced professionals in<br />

<strong>Islamic</strong> finance industry.<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> is not Exploiting its Full Potential of ‘Reverse Linkages’ Opportunities:<br />

Diagnostic analysis finds that <strong>Malaysia</strong> has huge potential of Reverse Linkages (RLs)<br />

opportunities through which the country can transfer its knowledge and expertise to other<br />

IDB member countries through win-win-win situation. In particular, IDB member<br />

countries can benefit from <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s <strong>Islamic</strong> financial system strengths; collaborate with<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> Science Academy; gain from SMEs development experiences; promote Halal<br />

industry; replicate Tabung Haji; acquire benefits from EXIM expertise; and benefit<br />

through <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Technical Corporation Programme. There<strong>for</strong>e, Reverse Linkages have<br />

been chosen as one of the major engagement pillars in the MCPS exercise.<br />

The Tenth <strong>Malaysia</strong> Plan, covering the period 2011-2015, targets an annual economic growth of<br />

6% and to raise GNI per capita from its current level of $9,575 to $12,139 by 2015 and to over<br />

$15,000 by 2020 through inclusive and sustainable growth. In order to achieve these objectives,<br />

the New <strong>Economic</strong> Model is being implemented through an <strong>Economic</strong> Trans<strong>for</strong>mation Program,<br />

which envisages an investment outlay of MYR1.4 trillion ($523 billion), of which 92% will be<br />

sourced from the private sector. The Plan goals can be realized through vigorously pursuing an<br />

inclusive and sustainable growth strategy which directly addresses regional disparities and<br />

income inequality.<br />

In conclusion, the remarkable story of socio-economic trans<strong>for</strong>mation of <strong>Malaysia</strong> resulted from<br />

visionary and inclusive development policies of the Government. However, at this stage of<br />

economic development, <strong>Malaysia</strong> appears to be facing the so-called “Middle Income Trap”. In<br />

the postwar era, like many countries in similar circumstances, <strong>Malaysia</strong> had rapidly moved into<br />

upper middle-income group by capitalizing on low-cost skilled labor, adoption of appropriate<br />

technology, pro-business environment, openness to FDI and trade, and effective privatization<br />

policies.<br />

In the next phase of its socio-economic development, <strong>Malaysia</strong> needs to embark on more<br />

inclusive development as well as build on new sources of growth, which can propel the economy<br />

to reach high income status by 2020. Similarly, the Government also needs to tackle the growing<br />

unemployment, particularly among the young graduates, as well as incentives to reverse brain<br />

3

drain. Further, the Government needs to fix the binding constraints, particularly related to private<br />

sector development.<br />

Both public and private sectors also need to fully exploit Reverse Linkages opportunities by<br />

transferring country’s knowledge and expertise to other IDB member countries in a mutually<br />

beneficial arrangement to achieve a win-win-win outcome. Further, South-South cooperation<br />

concept is considered a viable developmental tool, which can be enhanced through RLs. Within a<br />

sector-specific context, there are three critical players in the implementation of RL activities: (i)<br />

Provider institutions from <strong>Malaysia</strong>; (ii) Recipient countries / institutions of IDB member<br />

countries; and (iii) as a facilitator, the relevant Entities / Sector Departments in the IDB Group.<br />

The key findings of this <strong>Country</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Work</strong> help to identify focused programs under two<br />

key pillars namely Private Sector <strong>Development</strong> and Reverse Linkages of the “IDB Group<br />

Member <strong>Country</strong> Partnership Strategy <strong>for</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong>, 2012-2015: Partnering <strong>for</strong> Achieving the<br />

Status of High Income <strong>Country</strong>”. Further, it also helps to find out niche areas <strong>for</strong> the MCPS<br />

focused-programs to help the <strong>Malaysia</strong>n private sector by fixing some of the binding constraints.<br />

The IDB Group MCPS Report was launched by the Prime Minister of <strong>Malaysia</strong> and the President,<br />

IDB Group, during the <strong>Malaysia</strong>-IDB Investment Forum held on 9-11 May 2012 in Kuala<br />

Lumpur, <strong>Malaysia</strong>. The <strong>Country</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Work</strong> and the MCPS Report are placed on the IDB<br />

website www.isdb.org.<br />

During the Launching Ceremony, Dr. Ahmad Mohamed Ali (first from right) the President, IDB Group, presented a<br />

copy of the MCPS Report to Datuk Seri Najib Razak (center), the Prime Minister of <strong>Malaysia</strong>. On the occasion of<br />

the <strong>Malaysia</strong>-IDB Investment Forum held on 9-11 May 2012 in Kuala Lumpur, H.E. Dato’ Sri Mustapa Mohamed<br />

(first from left), Minister of International Trade and Industry of <strong>Malaysia</strong>, also attended the Launching Ceremony.<br />

4

I. DIAGNOSING THE MALAYSIAN ECONOMY:<br />

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT<br />

1. As part of its Vision 1440H (2020), the IDB Group embarks on Member <strong>Country</strong><br />

Partnership Strategy (MCPS) <strong>for</strong> its member countries, aimed at improving the efficiency and<br />

effectiveness of Group operations through close consultation with the key stakeholders. Be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

preparing any MCPS, it is extremely important to undertake a proper diagnostic of the country in<br />

order to understand key socio-economic challenges facing the country, particularly, identifying<br />

the binding constraints to achieving sustainable economic growth. Adopting this process, the IDB<br />

Group can assist the country in more effective way through the MCPS exercise.<br />

2. Be<strong>for</strong>e undertaking the MCPS <strong>for</strong> <strong>Malaysia</strong>, the IDB Group MCPS Team initiated the<br />

<strong>Country</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Work</strong> (CEW) aimed at providing analytical analysis of recent socio-economic<br />

development and major challenges facing the country. In particular, the CEW focuses on<br />

identifying binding constraints to achieving sustainable economic growth in <strong>Malaysia</strong>. Further,<br />

through extensive consultation with key stakeholders (public sector, private sector, business<br />

community, academia, civil society etc.), two main pillars namely (i) Private Sector<br />

<strong>Development</strong>; and (ii) Reverse Linkages have been identified <strong>for</strong> the IDB Group support over the<br />

next 4 to 5 years. There<strong>for</strong>e, in-depth diagnostics have been undertaken <strong>for</strong> these two sectors in<br />

order to find out niche areas <strong>for</strong> IDB Group interventions. This <strong>Country</strong> <strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Work</strong> uses the<br />

latest available in<strong>for</strong>mation and data from reliable national and international sources.<br />

3. The CEW document is structured as follows. Recent socio-economic developments of<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> are analysed in Section II. Major issues and challenges facing the country are<br />

highlighted in Section III. Using the Diagnostic Framework developed <strong>for</strong> this study, the binding<br />

constraints to sustainable economic growth are identified in Section IV. Diagnostic analysis of<br />

binding constraints to Private Sector <strong>Development</strong> is presented in Section V. Finally, the analysis<br />

of Reverse Linkages opportunities is given in Section VI.<br />

II.<br />

RECENT SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT<br />

4. Since gaining independence (more than five decades ago), <strong>Malaysia</strong> has achieved<br />

remarkable successes, particularly, in terms of socio-economic development. From a low-income<br />

agrarian country dependent on rubber and tin, <strong>Malaysia</strong> has emerged as a modern, industrial, and<br />

high-middle income nation with strong economic fundamentals. <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s successful<br />

implementation of various socio-economic policies over the years with significant support from<br />

the private sector, provide a solid plat<strong>for</strong>m on which the country is basing its next phase of<br />

development to achieve high income and developed nation status by 2020. Data on major<br />

5

macroeconomic indicators are given in Annex Table 1.1 and key developments are summarized<br />

below.<br />

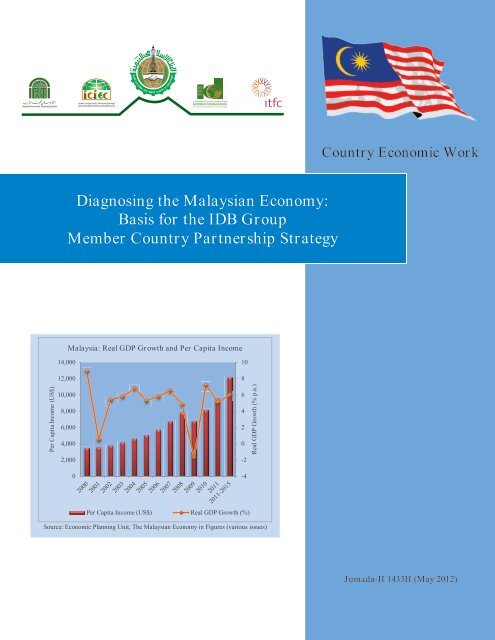

5. The country achieved strong and sustainable economic growth. Despite several<br />

regional and global challenges such as the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, the post-September<br />

11 (2001) recession, outbreaks of<br />

Severe Acute Respiratory<br />

Syndrome (SARS) in 2000-2003,<br />

avian flu in 2003-2006, increases<br />

in world oil and food prices in<br />

2007-2008, and global financial<br />

and economic crisis in 2008-2009,<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> has made significant<br />

strides in achieving sustainable<br />

economic growth, on average of<br />

over 5% during the decade (2000-<br />

2011), mainly due to strong<br />

economic fundamentals 2 (Figure<br />

1.1). In particular, in the post<br />

global economic crisis period,<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

-2<br />

-4<br />

Figure 1.1 Real GDP Growth, 2000-2011<br />

(% per annum)<br />

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011<br />

Source: <strong>Economic</strong> Planning Unit, The <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Economy in Figures (various Issues)<br />

after a contraction of economic growth by 1.6% in 2009, <strong>Malaysia</strong> has recovered fast as its real<br />

GDP grew by 7.2% in 2010, owing mainly to a rise in private domestic demand (both<br />

consumption and investment) and<br />

higher capacity utilization returning<br />

to pre-crisis period (currently<br />

Table 1.1 <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Sources of <strong>Economic</strong> Growth (% p.a.)<br />

around 85%). The Government<br />

Major Drivers of Growth 2010 2011<br />

stimulus packages and higher<br />

GDP 7.2 5.1<br />

development spending under the<br />

Domestic demand 10.7 6.5<br />

Ninth <strong>Malaysia</strong> Plan (2006-2010)<br />

Final consumption 3.6 5.9<br />

have also contributed to a rebound<br />

Private sector 3.5 3.7<br />

in economic activities. The sources<br />

Public sector 0.1 2.2<br />

of recent output growth Gross Fixed Capital Formation 2.1 1.3<br />

demonstrated a shift from<br />

Private sector 1.8 1.6<br />

externally-driven demand to<br />

Public sector 0.3 -0.3<br />

domestically-oriented demand with<br />

Change in stocks 5.0 -0.7<br />

the economy recorded a steady<br />

External demand -3.5 -1.4<br />

pace of growth of 5.1% in 2011.<br />

6. Domestic demand<br />

remains the major driver of<br />

economic growth. According to<br />

Exports of Goods & Services 10.6 4.0<br />

Imports of Goods & Services 14.1 5.4<br />

Source: Department of Statistics, <strong>Malaysia</strong> (May 2012)<br />

2 World <strong>Bank</strong> (2008), Growth Report by the Commission of Growth and <strong>Development</strong> has identified <strong>Malaysia</strong> as one<br />

of 13 countries in the world that has sustained growth of more than 7% <strong>for</strong> over 25 years (1967-1997).<br />

6

the Department of Statistics, <strong>Malaysia</strong> (May 2012), domestic demand contributed the largest<br />

share, accounting <strong>for</strong> 10.7 percentage points of total GDP growth in 2010 while the growth was<br />

contracted by 3.5 percentage points due to decline in external demand. Among domestic demand<br />

factors, private consumption contributed 3.5% and private investment 1.8% and will likely be the<br />

key growth drivers in 2011 and 2012, with rural areas benefitting from elevated commodity<br />

prices and urban areas from continued growth in the manufacturing and services sectors (Table<br />

1.1). Leading indicators such as rubber prices, stock market index, consumer sentiment index, and<br />

number of retrenched workers suggest that consumer spending will remain buoyant in the coming<br />

years. Solid employment and modest wage increase in line with improving external demand as<br />

well as buoyant commodity prices are also expected to support household income and<br />

consumption. Similarly, private investment is likely to rise with the implementation of projects<br />

under the Government’s <strong>Economic</strong> Trans<strong>for</strong>mation Program (ETP), which is being largely driven<br />

by the private sector.<br />

7. In terms of sectoral<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance, services sector<br />

remained the main source of<br />

economic growth. During 2000s,<br />

annual average growth in the services<br />

sector was 6.2%, attributed mainly<br />

due to strong per<strong>for</strong>mance in the<br />

finance, insurance, real estate and<br />

business services, wholesale and<br />

retail trade, hotel industry, and<br />

transport and communication (Figure<br />

1.2). The share of services sector in<br />

GDP also increased from 49.3% in<br />

2000 to 57.7% in 2010 (Figures 1.3<br />

and 1.4). Currently, 87% of the<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

-5<br />

-10<br />

Figure 1.2. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Sectoral Growth<br />

Rates, 2001-2010 (% per annum)<br />

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010<br />

Agriculture Manufacturing Services<br />

Source: <strong>Economic</strong> Planning Unit, The <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Economy in Figures (various Issues)<br />

Figure 1.3 Sectoral Shares in Gross Domestic<br />

Product of <strong>Malaysia</strong>, 2000 (% of total GDP)<br />

Figure 1.4. Sectoral Shares in Gross Domestic<br />

Product of <strong>Malaysia</strong>, 2010 (% of total GDP)<br />

Agriculture<br />

8.6% Mining<br />

10.6%<br />

Agriculture<br />

7.3% Mining<br />

7%<br />

Services<br />

49.3%<br />

Manufactrin<br />

g 27.6%<br />

Construction<br />

3.9%<br />

Manufactrin<br />

g 30.9%<br />

Services<br />

57.7%<br />

Construction<br />

3.3%<br />

Source: <strong>Economic</strong> Planning Unit, The <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Economy in Figures (2011)<br />

7

SMEs are concentrated in the services sector. During the last five years, SME growth<br />

outper<strong>for</strong>med the overall economic growth. However, there are some important areas of concern<br />

<strong>for</strong> SMEs such as the issue of low productivity, slow innovation and lack of financing, which<br />

need to be addressed effectively.<br />

8. The manufacturing sector was hit hard by the global recession but recovered<br />

remarkably in 2010. The manufacturing sector grew by 3.5% per annum during 2001-2010.<br />

Since the manufacturing sector is largely dependent on global demand, it was adversely affected<br />

by the global recession with a negative growth of 9.3% in 2009. This was largely due to the sharp<br />

deterioration in the demand <strong>for</strong> export-oriented products. Subsequently, the manufacturing<br />

sector’s share of GDP declined from 30.9% in 2000 to 27.6% in 2010 (Figures 1.3 and 1.4).<br />

Nonetheless, in 2010, the manufacturing sector strongly recovered with a positive growth of<br />

11.4%.<br />

9. Compared to other key sectors, growth in the agriculture sector remained relatively<br />

slow. During 2000s, the agriculture sector grew by 3.2% per annum. The slower growth was<br />

mainly attributed to a decline in the output of rubber and sawlogs, which is due to a reduction in<br />

rubber hectrage and controlled logging <strong>for</strong> sustainable <strong>for</strong>est management. However, increases in<br />

the production of oil palm, livestock and fisheries supported the growth of the agriculture sector.<br />

The share of agriculture in the GDP declined marginally from 8.6% in 2000 to 7.3% in 2010.<br />

10. <strong>Malaysia</strong>n economy remains at almost full employment level. The unemployment<br />

rate declined from the maximum level of 7.4% in 1986 to 3.1% in 2011. Due to global financial<br />

and economic crisis, the<br />

unemployment rate increased<br />

slightly to 3.7% in 2009. However,<br />

the employment situation<br />

recovered from the crisis and<br />

returned to the pre-crisis/ normal<br />

level of 3.1% in 2011(Figure 1.5).<br />

Recovery in employment appears<br />

in all the major sectors including<br />

manufacturing, construction,<br />

agriculture, and services. Real<br />

wages in the manufacturing sector<br />

have risen to fairly high compared<br />

to the pre-crisis level, owing to<br />

8.0<br />

7.0<br />

6.0<br />

5.0<br />

4.0<br />

3.0<br />

2.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.0<br />

Figure 1.5. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Unemployment Rate,<br />

1986-2011 (% p.a.)<br />

1986<br />

1987<br />

1988<br />

1989<br />

1990<br />

1992<br />

1993<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

2002<br />

2003<br />

2004<br />

2005<br />

2006<br />

2007<br />

2008<br />

2009<br />

2010<br />

2011<br />

Source: <strong>Economic</strong> Planning Unit, Government of <strong>Malaysia</strong> (www.epu.gov.my)<br />

persistently high number of available vacancies. The economy is expected to remain at full<br />

employment level with an estimated unemployment rate of 3.1% in 2015.<br />

11. Remarkable achievement in reducing poverty. Based on the national poverty line<br />

(defined as MYR750 per capita per month), poverty declined from 49.3% in 1970 to only 3.8% in<br />

2009, due to the implementation of targeted poverty eradication programs in both rural and urban<br />

areas. Hardcore poverty has reduced to almost zero in 2010. Despite this great success, some deep<br />

pockets of poverty remain among some groups and in remote parts of the country. In particular,<br />

8

the incidence of rural poverty<br />

(8.4%) was significantly higher<br />

compared to urban poverty of 1.7%<br />

in 2009 (Figure 1.6). During the<br />

Tenth <strong>Malaysia</strong> Plan period, the<br />

Government plans to reduce<br />

poverty further to 2% by 2015.<br />

Per Capita Income (US$)<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

Figure 1.7. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Real GDP Growth and<br />

Per Capita Income, 2000-2015<br />

14,000<br />

10<br />

12,000<br />

10,000<br />

8,000<br />

6,000<br />

4,000<br />

2,000<br />

0<br />

Figure 1.6. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Incidence of Poverty<br />

(% of households)<br />

12. In order to achieve highincome<br />

10<br />

advanced country status<br />

by 2020, <strong>Malaysia</strong>n economy<br />

0<br />

needs to grow by an average<br />

annual growth rate of around 6%<br />

Overall Poverty Urban Poverty Rural Poverty<br />

during the 10 th Plan Period<br />

(2011-2015), taking into account<br />

Source: <strong>Economic</strong> Planning Unit, Government of <strong>Malaysia</strong> (www.epu.gov.my)<br />

the risks associated, notably from<br />

the return of high food and fuel prices, sluggish recovery in developed nations, debt crisis in some<br />

European countries and USA, and instability due to volatile capital inflows. Further, the main<br />

risks to medium-term growth have been identified as re<strong>for</strong>m implementation risks, slow progress<br />

on fiscal consolidation, and the quality of public service delivery. <strong>Economic</strong> growth also needs to<br />

be based on more innovations with<br />

greater emphasis on the quality of<br />

capital and high labor efficiency in<br />

its production system through<br />

addressing the long-standing<br />

problem of brain drain and the lack<br />

of skilled labor. This translates into<br />

the course of achieving high<br />

income status that the country will<br />

have to raise current GNI per capita<br />

from $9,575 in 2011 to a highincome<br />

target of $12,139 by 2015<br />

and to over $15,000 by 2020<br />

through inclusive and sustainable<br />

growth (Figure 1.7).<br />

Per Capita Income (US$) Real GDP Growth (%)<br />

Source: <strong>Economic</strong> Planning Unit, The <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Economy in Figures<br />

13. Despite remarkable achievements during the last decade, <strong>Malaysia</strong> appears to be<br />

facing the so-called “Middle Income Trap”. In the post-war era, like many countries, <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

developed rapidly and moved into middle-income status. Out of 101 middle-income economies in<br />

1960, only 13 countries escaped this middle-income trap and became high income by 2008. 3 The<br />

factors that propelled high growth in <strong>Malaysia</strong> during its rapid growth phase were low-cost labor,<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

0<br />

-2<br />

-4<br />

Real GDP Growth (% p.a.)<br />

3 These countries include Equatorial Guinea, Greece, Hong Kong, China, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Mauritius, Portugal,<br />

Puerto Rico, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Spain and Taiwan.<br />

9

easy technology adoption, pro-business environment, and effective privatization policies, which<br />

weakened when the country reached upper-middle income level, <strong>for</strong>cing it to find new sources of<br />

growth in the coming years. 4 Much more is needed <strong>for</strong> transition from middle-income to highincome<br />

status. In particular, high level of investment (both domestic and <strong>for</strong>eign) with new<br />

technologies and improved quality of physical and human capital is needed. The business<br />

environment needs to be further improved. Innovation needs to be supported. Improved logistics<br />

and connectivity are vital <strong>for</strong> rapid growth. With regard to improving global competitiveness,<br />

conducive environment <strong>for</strong> innovation, technological enhancement, and skill-match are the key factors. 5<br />

III.<br />

MAJOR ISSUES/ CHALLENGES FACING THE COUNTRY<br />

14. Despite above-mentioned remarkable socio-economic per<strong>for</strong>mance achieved during the<br />

last decade, the country is facing a number of domestic as well as external challenges, which may<br />

affect its medium-term growth prospects. The major challenges facing the country are described<br />

below.<br />

15. The structural re<strong>for</strong>ms required in the manufacturing sector pose significant<br />

challenges in terms of strengthening skills-mix and maintaining its competitiveness. For<br />

many years, manufacturing has been the strongest sector in the country, which is now being<br />

progressively replaced by the services sector. However, the manufacturing sector is a major<br />

contributor to GDP growth. The structural re<strong>for</strong>ms required in this sector pose significant<br />

challenges in terms of skills mix and competition, and a strong desire to move up the technology<br />

chain to produce higher value-added technology-intensive products. There is a misalignment<br />

between the skills-mix produced by the current education and training systems and the needs of<br />

the manufacturing industry, which results in lower quality output. Moreover, there is an intense<br />

competition, both regionally and internationally, <strong>for</strong> appropriate human capital with high-end and<br />

high-tech skills <strong>for</strong> moving the industrial sector to higher level of development.<br />

16. Despite full employment rate in <strong>Malaysia</strong>, there is a worrying trend of growing<br />

unemployment among the young graduates. <strong>Malaysia</strong> has increasingly large and young<br />

population with approximately 50% of the population below 25 years of age. The unemployed<br />

graduates (with College Degree and above) increased from 27,700 in 2008 to 33,800 in 2010<br />

while unemployed graduates (with Diploma) rose from 26,400 to 31,700 during the same period.<br />

The increasing number of unemployed graduates was due to more graduates produced and joined<br />

the labour market. Although the number has increased, the unemployment rate of graduates<br />

decreased from 3.2% in 2008 to 3.1% in 2010 6 .<br />

17. <strong>Malaysia</strong> economy is facing brain drain. According to the World <strong>Bank</strong> (2011) 7 , the<br />

number of skilled <strong>Malaysia</strong>ns living abroad has tripled in the last two decades, with two out of<br />

every 10 <strong>Malaysia</strong>ns with tertiary education opting to leave <strong>for</strong> either OECD countries or<br />

4 World <strong>Bank</strong> (2012), “China 2030 Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative High-Income Society”.<br />

5 World <strong>Bank</strong> (2010), “Robust Recovery, Rising Risks”, Section III on Escaping the Middle-Income Trap.<br />

6 The Department of Statistics, Government of <strong>Malaysia</strong> (2011).<br />

7 World <strong>Bank</strong> Senior Economist Philip Schellekens, Kuala Lumpur, April 28, 2011.<br />

10

Singapore which took 54% of <strong>Malaysia</strong>'s graduate migrants, compared to just 20% in the 1990s.<br />

Some 15% went to Australia, 10% to the USA and 5% to Britain. These four countries accounted<br />

<strong>for</strong> over 80% of the entire <strong>Malaysia</strong>n Diaspora. Young <strong>Malaysia</strong>ns going overseas <strong>for</strong> higher<br />

education, in many instances opt to remain in those countries, contributing to brain drain.<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, the Government of <strong>Malaysia</strong> is focusing on enhancing employment opportunities <strong>for</strong><br />

people with higher education and research skills and reversing the brain drain.<br />

18. Income inequality continues to remain a challenge. Since 1970, income inequality<br />

steadily fell <strong>for</strong> two decades as Gini-coefficient (a measure of income inequality, which ranges<br />

from zero to 1 with a higher number indicating greater income inequality) declined from 0.51 in<br />

1970 to 0.46 in 1992, but more or<br />

less stagnated at this level. It is<br />

worth noting that <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

remained outside the efficient<br />

income inequality range of 0.25 –<br />

0.40 throughout the period (Figure<br />

1.8). The Gini-coefficient in<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> remained higher<br />

compared to other countries in the<br />

region such as India (0.37),<br />

Indonesia (0.37), Vietnam (0.38),<br />

China (0.42), and Philippines<br />

(0.44). Furthermore, the vast<br />

majority of the bottom 40%<br />

percentile of the society is<br />

Bumiputra (73% of the total) had<br />

0.60<br />

0.50<br />

0.40<br />

0.30<br />

0.20<br />

0.10<br />

0.00<br />

Figure 1.8. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Income Inequality<br />

(Gini-coefficent values)<br />

Source: <strong>Economic</strong> Planning Unit, Socio-<strong>Economic</strong> Statistics (April 2012)<br />

an average household income of MYR1,440. The Bumiputra generally have limited economic<br />

mobility and a weak ability to secure high-paying jobs in the private sector. Most of them are<br />

living in the rural areas with inadequate quality of education and health services, and limited<br />

access to quality utilities.<br />

19. According to recent household income surveys, income growth has been strong <strong>for</strong><br />

the top 20% of income earners while bottom 40% of households have experienced slow<br />

growth in average incomes. In order to reduce inequality, <strong>Malaysia</strong> needs to raise economywide<br />

income-earning opportunities by encouraging mobility of workers and improving labor<br />

market competition while reducing rigidities; promoting investment in human capital through<br />

enhancing basic education in under-served areas, improving vocational training system;<br />

strengthening employable and industry-led skills development. Reaching out to the vulnerable<br />

segment of the society, providing social protection <strong>for</strong> the poor by strengthening the poverty<br />

focus of social safety net programs, refining targeting mechanisms to reach the needy and moving<br />

towards a coordinated social protection system.<br />

20. There is a challenge is to reduce regional disparities through balanced development<br />

in five Growth Corridors, which is one of the key objectives of the Tenth <strong>Malaysia</strong> Plan.<br />

Among various states, Kuala Lumpur has the highest per capita GDP of MYR51 thousand while<br />

11

Kelantan with the lowest per<br />

capita GDP of MYR8 thousand in<br />

2009. Nine out of 15 states are<br />

having the per capita GDP below<br />

the national average GDP per<br />

capita (Figure 1.9). During the 9 th<br />

Plan period, the Government<br />

embarked on a number of<br />

initiatives to promote balanced<br />

regional development and<br />

accelerate growth in less<br />

developed geographic areas. As a<br />

result, five Growth Corridors<br />

namely Iskandar <strong>Malaysia</strong>,<br />

Northern Corridor <strong>Economic</strong><br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

Figure 1.9. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Inter-State Disparity, 2009<br />

(GDP Per Capita by State, 000 RM)<br />

Source: Tenth <strong>Malaysia</strong> Plan, 2011-2015<br />

National Average<br />

Region, East Coast <strong>Economic</strong> Region, Sarawak Corridor and Sabah <strong>Development</strong> Corridor, are<br />

identified with the key objective of reducing regional disparities during the 10 th <strong>Malaysia</strong> Plan<br />

(2011-2015).<br />

IV.<br />

DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS OF BINDING CONSTRAINTS TO SUSTAINABLE<br />

ECONOMIC GROWTH<br />

21. Compared to its major competing Asian countries, <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s economy experienced<br />

strong economic growth during 1990s but it slowed during 2000s. <strong>Malaysia</strong> had achieved an<br />

annual average growth of 7.4% during 1990s (Figure 1.10). However, this strong growth<br />

momentum could not be sustained and the growth rate slowed to 4.7% per annum during 2000s<br />

(Figure 1.11). The economy was expected to grow by 6% per annum during the 9 th Plan period<br />

China<br />

Singapore<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Vietnam<br />

Korea<br />

Taiwan<br />

India<br />

Thailand<br />

Indonesia<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Philippines<br />

Figure 1.10. Real GDP Growth in Selected<br />

Asian Countries (average 1990-2000)<br />

2.9<br />

7.5<br />

7.4<br />

7.3<br />

6.9<br />

6.3<br />

5.6<br />

5.2<br />

4.4<br />

4.0<br />

0.0 2.0 4.0 6.0 8.0 10.0<br />

9.8<br />

China<br />

India<br />

Vietnam<br />

Singapore<br />

Indonesia<br />

Philippines<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

Thailand<br />

Korea<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Taiwan<br />

Figure 1.11. Real GDP Growth in Selected<br />

Asian Countries (average 2001-2010)<br />

5.7<br />

5.2<br />

4.8<br />

4.7<br />

4.4<br />

4.2<br />

4.1<br />

3.9<br />

7.4<br />

7.3<br />

10.5<br />

0.0 2.0 4.0 6.0 8.0 10.0 12.0<br />

IMF, World <strong>Economic</strong> Outlook Database, September 2011<br />

12

(2006-2010) but its annual average growth rate remained 4.2%. Compared to 11 high growth<br />

per<strong>for</strong>ming Asian countries (China, India, Singapore, Korea Republic, Vietnam, Hong Kong,<br />

Taiwan, Indonesia, Thailand, and Philippines), <strong>Malaysia</strong> was at the 3 rd position (after China and<br />

Singapore) in terms of high growth during 1990s but over the last decade its momentum of<br />

growth noticeably slowed and its ranking moved to 7 th position, while the growth rates of several<br />

other countries in the region have improved during 2000s.<br />

22. Keeping in view the deceleration in growth during 2000s, it is important to find out what<br />

are the major causes and binding constraints to <strong>Malaysia</strong>n’s sustainable growth, using an<br />

appropriate growth diagnostic framework, which is described as follows.<br />

i. Growth Diagnostic Framework<br />

23. The widely used Growth Diagnostic Framework developed by Hausmann, Rodrik,<br />

and Velasco (2005), which considers low level of private investment as the only binding<br />

constraint, to economic growth, while ignoring the role of public investment and software of<br />

growth in achieving sustainable economic development. In this study, Hausmann, Rodrik, and<br />

Velasco framework is extended by including all the possible sources of economic growth (i.e.<br />

public investment, private investment and software of growth). The IDB Group MCPS Team <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong> has developed the problem tree, which provides a complete framework <strong>for</strong> diagnosing<br />

critical constraints to sustainable economic growth in <strong>Malaysia</strong> (Figure 1.12).<br />

24. The Growth Diagnostic Framework starts with private investment: First, it starts by<br />

asking what keeps the level of private investment low. Is private investment low due to low return<br />

on investment or high cost of financing? If it is low because of low social returns, is that due to<br />

poor geography (natural disasters) or poor human capital or physical infrastructure? If the<br />

problem is poor appropriately, is it due to government failures, market failures or both? If it is<br />

government failure, is that due to micro risks (i.e. high cost of doing business), macro risks (i.e.<br />

financial, monetary and fiscal instability) or restriction on <strong>for</strong>eign ownership <strong>for</strong> the <strong>for</strong>eign<br />

investors? If the impediment on private investment is due to high cost of financing, is that due to<br />

bad international finance (i.e. high interest rate and stringent conditionalities) or shortage of local<br />

finance. If the problem is of bad local finance, is that due to low private saving or poor<br />

intermediation of the banking system. 8<br />

25. Starting from the second part of the problem tree with regard to low level of public<br />

investment, it starts by asking what keeps the level of public investment low. Is public<br />

investment low because of budgetary constraints, leakages, or limited implementation capacity?<br />

If it is due to budgetary constraint, is it because of tight fiscal position, high borrowing cost or<br />

other development priorities? Are the leakages due to corruption or poor governance? Is limited<br />

implementation capacity due to weak institutions or poor human capital?<br />

8 For further detail on the Growth Diagnostic Framework, see Iqbal Z. and A. Suleman (July 2010), “Indonesia: Critical<br />

Constraints to Infrastructure <strong>Development</strong>”, and ADB-IDB-ILO (2010), Joint <strong>Country</strong> Diagnostic Study on “Indonesia:<br />

Critical <strong>Development</strong> Constraint”.<br />

13

Figure 1.12. General Growth Diagnostic Framework<br />

Critical Constraints to Sustainabale <strong>Economic</strong> Growth<br />

Low Level of<br />

Public Investment<br />

Weak Software of Growth<br />

Low Level of Private Investment<br />

(including FDI)<br />

Budgetary<br />

Constraint<br />

Tight<br />

Fiscal<br />

Position<br />

High<br />

Borrowing<br />

Costs<br />

Other<br />

<strong>Development</strong><br />

Priorities<br />

Leakages<br />

Corruption<br />

Poor<br />

Governance<br />

Limited<br />

Implementation<br />

Capacity<br />

Weak<br />

Institutions<br />

Lack of<br />

Huamn<br />

Capital<br />

Weak<br />

Business<br />

Sophistication on<br />

Limited<br />

Local<br />

Supplier<br />

Quantity<br />

Poor Local<br />

Supplier<br />

Quality<br />

Weak State of<br />

Cluster<br />

<strong>Development</strong><br />

Narrow<br />

Value Chain<br />

Breadth<br />

Weak<br />

Production<br />

Process<br />

Sophistication<br />

Low Level of<br />

Innovaion<br />

Low<br />

Capacity <strong>for</strong><br />

Innovation<br />

Poor Quality<br />

of Scientific<br />

Research<br />

Institutions<br />

Lower<br />

Company<br />

Spending on<br />

R&D<br />

Lack of<br />

Availability<br />

of Scientists<br />

and<br />

Engineers<br />

Low Govt.<br />

Procurement<br />

of Advanced<br />

Tech.<br />

Products<br />

Poor<br />

Reverse<br />

Linkages<br />

Low Social<br />

Returns<br />

Poor<br />

Geography<br />

(Natural<br />

Disasters)<br />

Low Return on<br />

Investment<br />

y<br />

Poor<br />

Physical and<br />

Human<br />

Capital<br />

Government<br />

Failures<br />

Low<br />

Appropriability<br />

Micro Risks<br />

(High Cost of<br />

Doing<br />

Business)<br />

Macro Risks<br />

(Financial,<br />

Monetary,<br />

and Fiscal<br />

Instability)<br />

Restriction on<br />

Foreign<br />

Ownership<br />

Market<br />

Failures<br />

In<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

Externalities<br />

Coordination<br />

Externalities<br />

High Cost of<br />

Finance<br />

Bad<br />

International<br />

Finance<br />

Shortage of<br />

Local<br />

Finance<br />

Low Private<br />

Savings<br />

Poor<br />

Intermediation<br />

Source: IDB Group MCPS Team (2012): An Extended Version of Growth Diagnostic Framework of Hausmann, Rodrik, and Velasco (2005)<br />

14

26. The final part of problem tree starts asking questions whether weak software of<br />

growth are due to weak business sophistication, low level of innovation, or poor reverse<br />

linkages. Is weak business sophistication due to poor quality of local supplier, weak state of<br />

cluster development, narrow value chain breadth, or weak production process sophistication?<br />

With regard to low level of innovation, is it due to low capacity <strong>for</strong> innovation, poor quality of<br />

scientific research institutions, lower company spending on research and development (R&D),<br />

lack of availability of scientists and engineers, or low government procurement of advanced<br />

technical products.<br />

27. Final branch of problem tree is whether poor Reverse Linkages (RLs) are constraining to<br />

growth (i.e. country is not fully exploiting RLs opportunities through sharing its knowledge and<br />

expertise to other IDB member countries).<br />

28. Using the growth diagnostic framework developed in this study, binding constraints<br />

to <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s sustainable economic growth are identified in terms of private investment, public<br />

investment, and software of growth as follows:<br />

ii.<br />

Constraints to Private Investment<br />

Low Level of Private Investment appears as binding constraint to sustainable<br />

economic growth<br />

29. Data show that during 2000s, economic growth was mainly constrained by<br />

significant decline in private investment. The key challenge in the 10 th <strong>Malaysia</strong> Plan is to<br />

stimulate private investment growth by 12.8% per annum over the Plan period (2011-2015).<br />

Prior to the Asian financial crisis,<br />

private investment as a<br />

percentage of GDP was at the<br />

maximum level of 32% in 1997<br />

(average annual private<br />

investment was 26.9% of GDP<br />

during 1990-1997), which<br />

drastically declined to 10.3% in<br />

2010 (Figure 1.13). During 2001-<br />

2010, real private investment<br />

growth remained 4.2% per<br />

annum while the real public<br />

investment grew by 4.3% per<br />

annum. In particular, during the<br />

Ninth Plan period (2006-2010),<br />

the moderation in private<br />

30.0<br />

25.0<br />

20.0<br />

15.0<br />

10.0<br />

5.0<br />

Figure 1.13. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Gross Fixed Capital<br />

Formation (% of GDP)<br />

Private Investment<br />

Public Investment<br />

Source: World <strong>Development</strong> Indicators, World <strong>Bank</strong> (1 Jan. 2012)<br />

investment was partially offset by higher public investment through stimulus packages in 2009<br />

and 2010. Achieving high income status by 2020 requires that the private sector must be placed in<br />

the driving seat of the economy through creating a more enabling environment. It is worth noting<br />

15

that the Government’s <strong>Economic</strong> Trans<strong>for</strong>mation Program with an amount of MYR1.4 trillion<br />

($523 billion) has targeted (92% of total investment) by the private sector (out of total, 73% by<br />

the local private investors and 27% by the <strong>for</strong>eign investors).<br />

30. Similar to local private investment, low level of <strong>for</strong>eign investment also appears to<br />

be a binding constraint to growth. Compared to competitor countries in the region, <strong>Malaysia</strong> is<br />

also lagging behind in terms of attracting FDI inflows. <strong>Country</strong> has begun to lose some FDI to<br />

China and other newly emerging destinations, including Vietnam, through relocation of existing<br />

factories and a reduced inflow of new investors. During 1990s, <strong>Malaysia</strong> attracted average FDI<br />

inflows of $4.9 billion (6.3% of GDP) per annum, which declined to $4.2 billion (2.9% of GDP)<br />

per annum during 2000s. While during the same period, FDI flows to China increased from $32.8<br />

Figure 1.14. Average Annual FDI<br />

Flows, 1990-2000 (% of GDP)<br />

Singapore<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Viet Nam<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

China<br />

Thailand<br />

Philippines<br />

Indonesia<br />

Korea<br />

Taiwan<br />

India<br />

3.7<br />

2.6<br />

1.7<br />

0.7<br />

0.7<br />

0.7<br />

0.4<br />

6.6<br />

6.3<br />

9.0<br />

0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0<br />

Source: UNCTADstat website (September 2011)<br />

12.0<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Singapore<br />

Viet Nam<br />

Thailand<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

China<br />

India<br />

Philippines<br />

Taiwan<br />

Indonesia<br />

Korea<br />

Figure 1.15. Average Annual FDI Flows,<br />

2001-2010 (% of GDP)<br />

5.9<br />

3.5<br />

2.9<br />

2.8<br />

1.7<br />

1.3<br />

1.0<br />

0.9<br />

0.7<br />

13.9<br />

20.2<br />

0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 25.0<br />

billion (4% of GDP) to $71.7 billion (2.9% of GDP); Hong Kong from $14.9 billion (9.4% of<br />

GDP) to $35.8 billion (18.8% of GDP); Singapore from $9.6 billion (11.7% of GDP) to $18.1<br />

billion (13.6% of GDP); and<br />

India from $1.9 billion (0.5% of<br />

GDP) to $16.6 billion (1.7% of<br />

GDP) (Figures 1.14 and 1.15). It<br />

is worth noting that the Asian<br />

financial crisis of 1997-98 caused<br />

significant outflows of <strong>for</strong>eign<br />

portfolio investment and <strong>for</strong>eign<br />

direct investment from <strong>Malaysia</strong>,<br />

which has not recovered yet.<br />

31. According to Growth<br />

Commission Report (2008) 9 , <strong>for</strong><br />

high and sustainable economic<br />

growth, investment rate of 25%<br />

50<br />

45<br />

40<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Figure 1.16. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Gross Domestic Savings and<br />

Gross Capital Formation, 2000-2010 (% of GDP)<br />

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010<br />

Source: <strong>Bank</strong> Negara <strong>Malaysia</strong> (website)<br />

Gross domestic savings (% of GDP)<br />

Gross capital <strong>for</strong>mation (% of GDP)<br />

9 World <strong>Bank</strong> (2008) Growth Report by the Commission of Growth and <strong>Development</strong>.<br />

16

of GDP or above is needed. The current overall investment level of 20.3% of GDP (public<br />

investment 10% and private investment 10.3% of GDP) in <strong>Malaysia</strong> is not adequate to support<br />

strong growth over the medium-term. Sustained higher levels of investment are critically<br />

necessary along with much-improved efficiency and returns on investment. Low investment rates<br />

in <strong>Malaysia</strong> do not appear to be due to insufficient savings (Figure 1.16). Saving rates in <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

has not changed much during 2000s and remained above 40% of GDP while total investment rate<br />

declined significantly and remianed average 21% of GDP during the same period.<br />

32. After identifying private investment as a binding constraint to sustainable economic<br />

growth, it is important to find out what are the binding constraints to private investment.<br />

The following sub sections explain what are (or not) binding constraints to private invesmtnet.<br />

(i)<br />

Availability and Cost of Finance do not appear binding constraints<br />

33. <strong>Country</strong> has huge internal resource surplus (S-I), thereby no shortage of local<br />

financing. During 2000s, overall investment rate remained below the domestic saving rate,<br />

leaving the internal resource surplus (saving-investment gap) between 17–23% of GDP per<br />

annum, which indicates abundant availability of domestic financing.<br />

34. <strong>Country</strong>’s <strong>Bank</strong>ing sector has ample liquidity and remained well-capitalised. In<br />

banking system, loans-to-deposits ratio has steadily increased from 70.5% in 2006 to a<br />

com<strong>for</strong>table level of 80.9% in 2011. Total outstanding loans from the banking system in <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

has significantly increased from MYR315 billion in 2000 to MYR1,004 billion in 2011, however,<br />

it remained lower compared to the<br />

cumulative deposits which<br />

increased from MYR363 billion to<br />

MYR1,300 billion during the same<br />

period, leaving the surplus liquidity<br />

of MYR255 billion ($82.6 billion)<br />

in 2011. During 2000-2011, the<br />

average growth in loans by<br />

commercial banks was 11.3% while<br />

the growth in deposits was 12.5%.<br />

It is worth noting that the average<br />

lending rate by commercial banks<br />

declined from 7.7% in 2000 to<br />

5.1% in 2011 (Figure 1.17). The<br />

<strong>Malaysia</strong>n banking system and<br />

bond market have ample liquidity<br />

to meet borrowers’ medium-term<br />

Loan-Deposit Ratio<br />

100.0<br />

90.0<br />

80.0<br />

70.0<br />

60.0<br />

50.0<br />

40.0<br />

30.0<br />

20.0<br />

10.0<br />

-<br />

Figure 1.17. <strong>Bank</strong>ing System in <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Loan-Deposit<br />

2000<br />

Ratio and Average Lending Rate (% p.a.)<br />

2001<br />

2002<br />

2003<br />

2004<br />

Source: <strong>Bank</strong> Negara <strong>Malaysia</strong>, Annual Reports (various issues)<br />

2005<br />

2006<br />

Loan-Deposit Ratio (end of year) Average Lending Rate (%)<br />

funding needs. Healthy domestic demand is expected to drive growth in <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s banking<br />

sector in the medium-term as public and private projects identified in <strong>Economic</strong> Trans<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

Program (worth MYR1.4 trillion) will help to stimulate lending.<br />

2007<br />

2008<br />

2009<br />

2010<br />

2011<br />

10.0<br />

8.0<br />

6.0<br />

4.0<br />

2.0<br />

0.0<br />

Average Lending Rate (% p.a.)<br />

17

(ii) Low Returns to Investments appears as binding constraint<br />

35. <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s social returns to investment is lower compared to Singapore; China;<br />

Philippines and India while higher than Indonesia, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Thailand and<br />

Korea. Slow economic growth can also be explained by lower returns to economic activity,<br />

which in turn can be on account of low social returns to investment and or low appropriability of<br />

the returns. Social returns (or returns to society) can be affected by the level of investment in<br />

human capital, infrastructure, or public goods that compliment private investment. Inadequate<br />

investment in these complementary factors can lead to low social returns by dampening the<br />

productivity of factors of production and increasing the cost of doing business, which in turn<br />

lower the returns to investment. A<br />

comparison of social returns<br />

across selected Asian countries<br />

suggest that <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s average<br />

annual social returns to investment<br />

during 2000-2010 were 22.2%,<br />

which were lower compared to<br />

Singapore (26.8%); China<br />

(24.7%); Philippines (23.6%) and<br />

India (23%) while higher than<br />

Indonesia (20.4%), Vietnam<br />

(20.2%), Hong Kong (19.7%),<br />

Thailand (16.7%) and Korea<br />

(15.3%) (Figure 1.18). A<br />

relatively low level of social<br />

returns could be a symptom of<br />

deficiencies in human capital. 10<br />

30.0 26.8 24.7 23.6 23.0<br />

25.0<br />

22.2 20.4 20.2 19.7<br />

20.0<br />

15.0<br />

10.0<br />

5.0<br />

0.0<br />

Figure 1.18. Returns to Investment in Selected<br />

Asian Countries (%)<br />

16.7 15.3<br />

Data Source: World <strong>Bank</strong>, World <strong>Development</strong> Indicators<br />

Note: Return to investment is estimated as the ratio of real GDP growth rate and<br />

gross capital <strong>for</strong>mation as % of GDP.<br />

(iii) Macroeconomic Risks do not appear as binding constraints<br />

36. <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s macroeconomic per<strong>for</strong>mance is sound with significant current account<br />

and trade account surpluses, low inflation rate, and low level of <strong>for</strong>eign debt. However,<br />

fiscal deficit appears to be a concern. Per<strong>for</strong>mance of major macroeconomic indicators is<br />

described below.<br />

37. <strong>Country</strong> has significant current account and trade surplus, and sufficient level of<br />

<strong>for</strong>eign exchange reserves. The country’s current account surplus increased substantially from<br />

9% of GDP in 2000 to 17.7% in 2008. However, due to the adverse impact of the global financial<br />

and economic crisis, the current account surplus fell to 11.5% of GDP in 2011. Higher <strong>for</strong>eign<br />

capital inflows including FDI and workers’ remittances improved the balance of payments<br />

position of the country. Similarly, during the last decade, the country enjoyed maximum trade<br />

10 For detail on social returns on investment, see ADB-IDB-ILO joint <strong>Country</strong> Diagnostic study “Indonesia: Critical<br />

<strong>Development</strong> Constraints” (2010).<br />

18

surplus of 19.8% of GDP in 2005,<br />

which declined to 13.4% of GDP<br />

in 2011, due to adverse impact of<br />

global economic crisis (Figure<br />

1.19). <strong>Malaysia</strong>’s <strong>for</strong>eign exchange<br />

reserves improved significantly<br />

from $29.9 billion (5.1 months of<br />

retained imports) in 2001 to $133.6<br />

billion (9.6 months of retained<br />

imports) as of end-2011. It is worth<br />

noting that post-global financial<br />

crisis, <strong>Malaysia</strong> experienced large<br />

short-term capital inflows, which<br />

exerted significant upward pressure<br />

on the exchange rate.<br />

25.0<br />

20.0<br />

15.0<br />

10.0<br />

5.0<br />

0.0<br />

Figure 1.19. <strong>Malaysia</strong>: Current Account and Merchandise<br />

Trade Account Balance, 2000-2011 (% of GDP)<br />

Current Account Balance (% of GDP)<br />

Trade balance (% of GDP)<br />

Sources: Data <strong>for</strong> current account balance, IMF World <strong>Economic</strong> Outlook<br />

(April 2012); and Data <strong>for</strong> trade balance, Department of Statistics, <strong>Malaysia</strong><br />

(website) (taken as trade balance as share of GDP at purchaser’s price)<br />

38. <strong>Malaysia</strong> has been<br />