You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

34 What <strong>to</strong> see<br />

What <strong>to</strong> see<br />

35<br />

City Walls (Gradski bedemi) C/D- 2. Once the largest<br />

city-fortress in the entire Republic of Venice, Zadar’s walls<br />

allowed it <strong>to</strong> retain more of its independence than most of<br />

its neighbouring cities, and meant that it was never captured<br />

by the Turks. Previously, there were even more fortifications<br />

than there are now, but what are left are put <strong>to</strong> good use,<br />

with delightful parks and promenades on <strong>to</strong>p of them (see<br />

below). Take a look inside doors such as the one on Five Wells<br />

Square - you can see huge empty spaces inside once used<br />

as military s<strong>to</strong>rage facilities.On <strong>to</strong>p of the bastion above the<br />

Harbour Gate is a promenade called the Muraj - a peaceful<br />

vantage point over the mainland opposite and the people<br />

crossing the bridge. One of the large yellow buildings up there<br />

is one of Zadar’s old newspaper presses.<br />

Cultural Heritage<br />

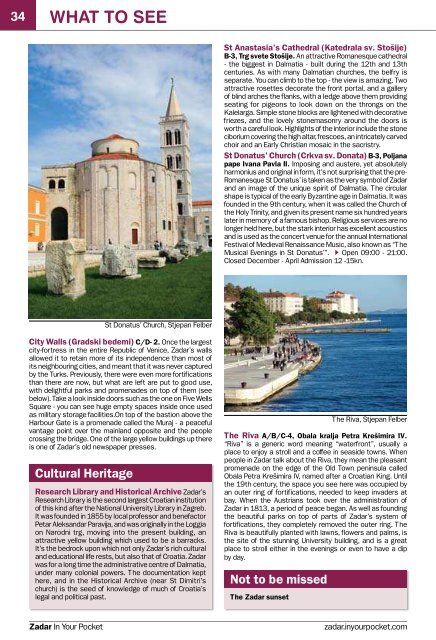

St Donatus’ Church, Stjepan Felber<br />

Research Library and His<strong>to</strong>rical Archive Zadar’s<br />

Research Library is the second largest Croatian institution<br />

of this kind after the National University Library in Zagreb.<br />

It was founded in 1855 by local professor and benefac<strong>to</strong>r<br />

Petar Aleksandar Paravija, and was originally in the Loggia<br />

on Narodni trg, moving in<strong>to</strong> the present building, an<br />

attractive yellow building which used <strong>to</strong> be a barracks.<br />

It’s the bedrock upon which not only Zadar’s rich cultural<br />

and educational life rests, but also that of Croatia. Zadar<br />

was for a long time the administrative centre of Dalmatia,<br />

under many colonial powers. The documentation kept<br />

here, and in the His<strong>to</strong>rical Archive (near St Dimitri’s<br />

church) is the seed of knowledge of much of Croatia’s<br />

legal and political past.<br />

St Anastasia’s Cathedral (Katedrala sv. S<strong>to</strong>šije)<br />

B-3, Trg svete S<strong>to</strong>šije. An attractive Romanesque cathedral<br />

- the biggest in Dalmatia - built during the 12th and 13th<br />

centuries. As with many Dalmatian churches, the belfry is<br />

separate. You can climb <strong>to</strong> the <strong>to</strong>p - the view is amazing. Two<br />

attractive rosettes decorate the front portal, and a gallery<br />

of blind arches the flanks, with a ledge above them providing<br />

seating for pigeons <strong>to</strong> look down on the throngs on the<br />

Kalelarga. Simple s<strong>to</strong>ne blocks are lightened with decorative<br />

friezes, and the lovely s<strong>to</strong>nemasonry around the doors is<br />

worth a careful look. Highlights of the interior include the s<strong>to</strong>ne<br />

ciborium covering the high altar, frescoes, an intricately carved<br />

choir and an Early Christian mosaic in the sacristry.<br />

St Donatus’ Church (Crkva sv. Donata) B-3, Poljana<br />

pape Ivana Pavla II. Imposing and austere, yet absolutely<br />

harmonius and original in form, it’s not surprising that the pre-<br />

Romanesque St Donatus’ is taken as the very symbol of Zadar<br />

and an image of the unique spirit of Dalmatia. The circular<br />

shape is typical of the early Byzantine age in Dalmatia. It was<br />

founded in the 9th century, when it was called the Church of<br />

the Holy Trinity, and given its present name six hundred years<br />

later in memory of a famous bishop. Religious services are no<br />

longer held here, but the stark interior has excellent acoustics<br />

and is used as the concert venue for the annual International<br />

Festival of Medieval Renaissance Music, also known as “The<br />

Musical Evenings in St Donatus’”. QOpen 09:00 - 21:00.<br />

Closed December - April Admission 12 -15kn.<br />

The Riva A/B/C-4, Obala kralja Petra Krešimira IV.<br />

“Riva” is a generic word meaning “waterfront”, usually a<br />

place <strong>to</strong> enjoy a stroll and a coffee in seaside <strong>to</strong>wns. When<br />

people in Zadar talk about the Riva, they mean the pleasant<br />

promenade on the edge of the Old Town peninsula called<br />

Obala Petra Krešimira IV, named after a Croatian King. Until<br />

the 19th century, the space you see here was occupied by<br />

an outer ring of fortifications, needed <strong>to</strong> keep invaders at<br />

bay. When the Austrians <strong>to</strong>ok over the administration of<br />

Zadar in 1813, a period of peace began. As well as founding<br />

the beautiful parks on <strong>to</strong>p of parts of Zadar’s system of<br />

fortifications, they completely removed the outer ring. The<br />

Riva is beautifully planted with lawns, flowers and palms, is<br />

the site of the stunning University building, and is a great<br />

place <strong>to</strong> stroll either in the evenings or even <strong>to</strong> have a dip<br />

by day.<br />

Not <strong>to</strong> be missed<br />

The Zadar sunset<br />

The Riva, Stjepan Felber<br />

Statue of Petar Zoranić<br />

On St Chrysogonus’ square is a statue of a man with<br />

rather muscular legs. This is Petar Zoranić, the writer of<br />

the first novel in Croatian. Born in Zadar, he was the son of<br />

a family of nobles from Nin. The beauty of the surrounding<br />

mountains and the sea was his inspiration and his theme<br />

in Planine (“Mountains”), written in 1536, a pas<strong>to</strong>ral<br />

romance and a product of the Renaissance in Zadar at<br />

that time - a time when the city was under siege by the<br />

Turks, but art and culture prospered within.<br />

Churches<br />

When you look in<strong>to</strong> it, you could be forgiven for thinking<br />

that all the people of Zadar have done through the<br />

centuries is build churches. Looking at this gives you a<br />

good idea of exactly how long the city has been standing,<br />

and how rich that life has been. Here are the main<br />

highlights. Note: churches are normally only open for Mass<br />

- each has its own timetable. All churches expect you <strong>to</strong><br />

cover up: short shorts and tiny <strong>to</strong>ps will not only raise<br />

eyebrows, but you may be handed a cover-up or refused<br />

admittance.<br />

Church of Our Lady of Health (Crkva Gospe od<br />

“Kaštela” (Zdravja)) A-3, Braće Bilišić 1. In the green<br />

park by Three Wells Square (see Essential Zadar) is the<br />

little orange Church of Our Lady of Health, one of the city’s<br />

best-loved churches. It lies in the quiet old neighbourhood of<br />

Kampo Kaštelo. Built in 1703 on the site of two much older<br />

churches, it contains a copy of a famous painting “Our Lady<br />

of Kaštelo”, the original of which is now in the Permanent<br />

Exhibition of Religious Art (see The Silver and Gold of the<br />

City of Zadar ).<br />

Church of St Mary “de Pusterla” S<strong>to</strong>morica (Crkva<br />

sv. Marije “de Pusterla” S<strong>to</strong>morica) C-4, Mihovila<br />

Pavlinovića 12. The foundations of this tiny Early Christian<br />

church (11th Century) were found in 1880 near Hotel Zagreb<br />

on the northern edge of the peninsula, and uncovered in<br />

the ‘60s. The floor plan of the church is fascinating: the<br />

five semicircular apses (typical of early Dalmatian church<br />

architecture) and the semicircular portal surrounding the<br />

central space give it an unusual six-leaved clover shape.<br />

St Andrew’s and St Peter the Elder’s (Crkva<br />

sv. Petra Starog i Sv. Andrije) C-2, Hrvoja Vukčića<br />

Hrvatinića 10. On the corner of Ulica Dalmatinskog Sabora<br />

and Ulica Hrvoja Vukčića Hrvatinića (near the market), the<br />

simple frontage of St Andrew’s has an unremarkable 17th<br />

century facade, but other parts date back <strong>to</strong> the 5th and 6th<br />

centuries. Through the apse you enter the very unusual church<br />

of St Peter the Elder, also from the early Middle Ages. Both<br />

contain fragments of ancient frescoes, and the atmospheric<br />

interiors are now used as exhibition spaces.<br />

St Chrysogonus’ Church (Crkva sv. Krševana)<br />

C-2, Poljana Pape Aleksandra III 2. A beautifully preserved<br />

little Romanesque church, consecrated in 1175, originally<br />

belonging <strong>to</strong> a Benedictine monastery that once s<strong>to</strong>od<br />

nearby. The front is quite simple, while on the sides are<br />

delightful barley-sugar twist columns, and <strong>to</strong> the rear three<br />

semicircular apses, the central one decorated with a gallery.<br />

The interior is also pleasingly simple, with many remains of<br />

frescoes. The high altar was built in 1701 by citizens who were<br />

spared from plague. In 1717 white marble statues of Zadar’s<br />

four patron saints were erected on the altar.<br />

St Dimitri’s Church (Crkva sv. Dimitrija) D-4,<br />

Mihovila Pavlinovića. St Dimitri’s is an unusual example of<br />

Neo-Classical architecture in Dalmatia. It was completed in<br />

1906 by Viennese architect Karl Susan, and has an unusual<br />

central cupola. It was part of an educational complex, and<br />

two of the buildings now house the His<strong>to</strong>rical Archives, the<br />

University’s Faculty of Humanities and the Croatian Academy<br />

of Arts and Sciences.<br />

Not <strong>to</strong> be missed<br />

Saint Mary’s Church Campanile from 1105<br />

Zadar’s Protection Squad<br />

Zadar has four patron saints. If that seems a bit excessive,<br />

read the His<strong>to</strong>ry section, you’ll soon understand why.<br />

Here’s the gang:<br />

St Simeon - Sveti Šimun<br />

Saint Simeon (or Simon) is said <strong>to</strong> have been present at<br />

the birth of Jesus, which is probably why women wishing<br />

<strong>to</strong> bear a son appeal <strong>to</strong> him. This also explains why he is<br />

the most popular patron saint: around here, the birth of<br />

a son occasions much quaffing of rakija and Tarzan-like<br />

chest-beating. The saint’s body is kept in an amazing<br />

casket which is opened every year on Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 8 (see<br />

Essential Zadar).<br />

St Chrysogonus - Sveti Krševan<br />

St Chrysogonus (or Grisogono in Italian) is the main patron<br />

saint of the city: the City of Zadar Day celebrations are<br />

always held on St Chrysogonus’ day (November 24).<br />

You can see him riding a horse on Zadar’s coat of arms<br />

and flag. He was persecuted and beheaded by Roman<br />

Emperor Diocletian (who built the palace at Split).<br />

St Anastasia - Sveta S<strong>to</strong>šija<br />

St Anastasia was also martyred under Diocletian, and is<br />

also said <strong>to</strong> have been present at the birth of Christ. She<br />

cared for persecuted Christians, and unfortunately met<br />

the same fate herself - she was <strong>to</strong>rtured and beheaded.<br />

Her remains now lie in a marble reliquary in the Cathedral,<br />

which is dedicated <strong>to</strong> her.<br />

St Zoilo - (no translation available)<br />

The least well-known of Zadar’s keepers, St Zoilo<br />

rescued St Chrysogonus’ body when it was washed<br />

up on the shore, and buried it at his home in Venice.<br />

Although Chrysogonus had been beheaded, his body was<br />

miraculously whole. For this and other kind acts, St Zoilo’s<br />

relics were brought <strong>to</strong> Zadar after his death.<br />

www.inyourpocket.com<br />

Zadar In Your Pocket<br />

zadar.inyourpocket.com<br />

zadar.inyourpocket.com<br />

Summer 2011