Antimicrobial Drugs

Antimicrobial Drugs

Antimicrobial Drugs

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

M34_ADAM9811_03_SE_CH34.QXD 12/30/09 1:16 PM Page 482<br />

482 Unit 5 The Immune System<br />

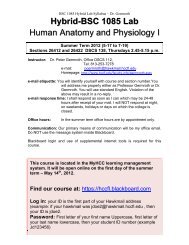

Resistant<br />

organism<br />

Antibiotic<br />

Time<br />

➤ Figure 34.2 Acquired resistance<br />

1. Infection<br />

2. Antibiotic kills all organisms<br />

except the resistant one.<br />

3. Resistant organism that<br />

remained has rapidly divided<br />

to infect the client. Antibiotic<br />

is no longer effective.<br />

Health care providers play important roles in delaying the<br />

emergence of resistance. The following are five principles<br />

recommended by the CDC:<br />

● Prevent infections whenever possible. It is always easier<br />

to prevent an infection, than to treat one. This includes<br />

teaching the patient the importance of getting<br />

immunizations.<br />

● Use the right drug for the infection. Infections should be<br />

cultured so that the offending organism can be identified<br />

and the correct drug chosen (see Section 34.6).<br />

● Restrict the use of antibiotics to those conditions<br />

deemed medically necessary. Antibiotics should only be<br />

prescribed when there is a clear rationale for their use.<br />

● Advise the patient to take anti-infectives for the full<br />

length of therapy, even if symptoms disappear before the<br />

regimen is finished. Prematurely stopping antibiotic<br />

therapy allows some pathogens to survive, thus<br />

promoting the development of resistant strains.<br />

● Prevent transmission of the pathogen by using proper<br />

infection control procedures. This includes the use of<br />

standard precautions and teaching patients methods of<br />

proper hygiene for preventing transmission in the home<br />

and community settings.<br />

In most cases, antibiotics are given when there is clear evidence<br />

of bacterial infection. Some patients, however, receive<br />

antibiotics to prevent an infection, a practice called<br />

prophylactic use, or chemoprophylaxis. Examples of patients<br />

who might receive prophylactic antibiotics include those<br />

who have a suppressed immune system, those who have experienced<br />

deep puncture wounds such as from dog bites, or<br />

those who have prosthetic heart valves and are about to have<br />

medical or dental procedures.<br />

34.6 Selection of an<br />

Effective Antibiotic<br />

The selection of an antibiotic that will be effective against a<br />

specific pathogen is an important task of the health care<br />

provider. Selecting an incorrect drug will delay proper treatment,<br />

giving the microorganisms more time to invade.<br />

Prescribing ineffective antibiotics also promotes the development<br />

of resistance, and may cause unnecessary adverse<br />

effects in the patient.<br />

Ideally, laboratory tests should be conducted to identify the<br />

specific pathogen prior to beginning anti-infective therapy.<br />

Lab tests may include examination of urine, stool, spinal<br />

fluid, sputum, blood, or purulent drainage for microorganisms.<br />

Organisms isolated from the specimens are grown in the<br />

laboratory and identified. After identification, the laboratory<br />

tests several different antibiotics to determine which is most<br />

effective against the infecting microorganism. This process of<br />

growing the pathogen and identifying the most effective antibiotic<br />

is called culture and sensitivity (C&S) testing.<br />

Because antibiotic therapy alters the composition of infected<br />

fluids, samples should be collected prior to starting<br />

pharmacotherapy. However, laboratory testing and identification<br />

may take several days and, in the case of viruses, several<br />

weeks. If the infection is severe, therapy is often begun<br />

with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, one that is effective against a<br />

wide variety of different microbial species. After laboratory<br />

testing is completed, the drug may be changed to a narrowspectrum<br />

antibiotic, one that is effective against a smaller group<br />

of microbes or only the isolated species. In general, narrowspectrum<br />

antibiotics have less effect on normal host flora,<br />

thus causing fewer side effects. For mild infections, laboratory<br />

identification is not always necessary; skilled health<br />

care providers are often able to make an accurate diagnosis<br />

based on patient signs and symptoms.<br />

In most cases, antibacterial therapy is best conducted using<br />

a single drug. Combining two antibiotics may actually<br />

decrease each drug’s efficacy, a phenomenon known as<br />

antagonism. If incorrect combinations are prescribed, the<br />

use of multiple antibiotics also has the potential to promote<br />

resistance. Multidrug therapy is warranted, however, if several<br />

different organisms are causing the patient’s infection<br />

or if the infection is so severe that therapy must be started<br />

before laboratory tests have been completed. Multidrug<br />

therapy is clearly warranted in the treatment of tuberculosis<br />

or in patients infected with HIV.<br />

One common adverse effect of anti-infective therapy is the<br />

appearance of secondary infections, known as superinfections,<br />

# 102887 Cust: PE/NJ/CHET Au: ADAMS Pg. No. 482<br />

Title: Pharmacology for Nurses Server: Jobs2<br />

C/M/Y/K<br />

Short / Normal<br />

DESIGN SERVICES OF<br />

S4CARLISLE<br />

Publishing Services