Volume 7 Number 2 July 2006 - JICS - The Intensive Care Society

Volume 7 Number 2 July 2006 - JICS - The Intensive Care Society

Volume 7 Number 2 July 2006 - JICS - The Intensive Care Society

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 7<br />

<strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

Price £15<br />

● Lessons Learned From <strong>The</strong> London Bombings<br />

● Organ Donation - Time For A Rethink?<br />

● <strong>The</strong> ACUTE Initiative<br />

● Best Interests - Who Decides?<br />

This issue is supported by<br />

an educational grant from<br />

Lilly Critical <strong>Care</strong><br />

● Tight Glycaemic Control<br />

● Pericardial Tamponade

Journal produced by <strong>The</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

29B Montague Street, London, WC1B 5BW.<br />

Tel: 020 7291 0690 Fax: 020 7580 0689 Website: www.ics.ac.uk<br />

Editor: Dr. Bruce Taylor, Consultant in <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> and Anaesthesia.<br />

Department Of Critical <strong>Care</strong> Medicine, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Cosham, Portsmouth, Hampshire PO6 3LY.<br />

Email: bruce.taylor@porthosp.nhs.uk<br />

Editorial Assistant: Jemma Regan Email: jemma@ics.ac.uk

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Editorial 3<br />

Contents<br />

Editorial / President’s Report<br />

03 Editorial B Taylor<br />

04 President’s Report A Batchelor<br />

Meetings Reports<br />

06 Annual Spring Meeting Report T Jackson<br />

09 Annual Spring Meeting Exhibition Report M Moore<br />

10 Poster Presentation Winner<br />

11 SKINT Workshop D Goldhill<br />

Research & Development Update<br />

12 Tracman Update L Morgan<br />

Surveys & Audits<br />

13 Designated Consultants for the Inter-Hospital G Allen, P Farling<br />

Transfer of Patients with Brain Injury – a survey of B A Mullan<br />

practice among neurosurgical units in the UK and Ireland<br />

16 Tight Glycaemic Control in Scottish ICUs E S Jack, M J E Neil<br />

19 An Audit of Hypoglycaemia in Critical <strong>Care</strong> A N Thomas<br />

E M Boxall<br />

G Sabbagh<br />

J Eddleston<br />

T Dunne, A Stevens,<br />

P Murphy<br />

Original Articles<br />

23 Best Interests -Who Decides? C Danbury<br />

25 <strong>The</strong> Point of Death J Radcliffe Richards<br />

27 Pakistan Earthquake A Charters<br />

29 Not Left to Your Own Devices S Ludgate<br />

30 Diagnosis and Management of PVL-associated C Day<br />

Staphylococcal Infections<br />

32 Reflections on the clinical learning points from the PJ Shirley, M Thavasothy<br />

Royal London Hospital <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Unit D McAuley, D Kennedy<br />

following <strong>July</strong> 7th 2005 terrorist attacks<br />

G Mandersloot<br />

V Verma, M Healy<br />

35 Cardiac Tamponade Following Insertion of An R Davis, M B Walker<br />

Implantable Defibrillator<br />

37 Bedside Ultrasound of Pleural Effusions by UK D Y Ellis<br />

Intensivists; How Much Training Do we Need? R M Grounds<br />

A Rhodes<br />

38 Update on the ACUTE initiative G Perkins<br />

40 Lemmingaid - Kafka and the Clinical Director Wood & Trees<br />

(Metamorphosis)<br />

CATmaker Reviews<br />

42 Rescue Angioplasty vs Repeat Thrombolysis in A Gershlick<br />

Acute MI?<br />

44 Furosemide and albumin improve oxygenation in D MacNair<br />

a small group of patients with Acute Lung Injury B H Cuthbertson<br />

46 Corticosteroids in late ARDS K Steinberg<br />

48 Non-invasive ventilation in patients with acute J L Moran<br />

cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: a meta-analysis<br />

Manpower<br />

50 Manpower Census R Kishen<br />

Correspondence<br />

51 Aussie Training – a Perspective from Down-Under S Blakeley<br />

52 National Critical Incidents Reporting Scheme J Mitchell<br />

52 National Critical Incidents Reporting Scheme A N Thomas<br />

53 Guidelines for clearing suspected spinal injury in E Thomas<br />

unconscious patients<br />

Miscellaneous<br />

55 Industry Members 60 Secretariat Report<br />

56 Council Members 62 Meetings Diary<br />

58 Advertising and Sponsorship Rate Card<br />

<strong>JICS</strong> Editorial Board<br />

Bruce Taylor (Editor)<br />

Jemma Regan (Editorial Assistant)<br />

Carl Waldmann<br />

David Goldhill<br />

CAT reviews;<br />

Chris Cairns<br />

Brian Cuthbertson<br />

Sheena Hubble<br />

<strong>The</strong> Editor writes<br />

It is with great sadness that we heard of the recent death of another<br />

popular and highly respected colleague. We hope to include a tribute<br />

to Fiona Clarke in the next edition – which will be the second time in<br />

just over a year that that we have reflected on the death of a young,<br />

talented intensivist who, for reasons that remain enigmatic, chose to<br />

end their own life. Such a devastating loss causes us to stop and<br />

think; the common characteristic in both instances seems to be that<br />

even close colleagues didn’t see it coming – which inevitably leads us<br />

all to think about our own colleagues, and whether we should have<br />

concerns about their (and perhaps even our own) wellbeing.<br />

It also at least raises the question of whether we are as resilient about<br />

the effects of the job that we do as we might like to think we are. You<br />

don’t choose a career in intensive care unless you enjoy a challenge,<br />

and the unpredictably of the work that goes with the territory.<br />

However, an integral part of the work also includes difficult decisions,<br />

and the management of situations that can be both harrowing and<br />

distressing for all involved. Asking colleagues how they cope with<br />

such challenges produces responses ranging between ‘I don’t do<br />

stress’ from some of the more outwardly robust, to that of a capable<br />

and enthusiastic SpR trainee who decided not to pursue their<br />

preferred career because they felt unable to handle the emotional<br />

pressures that come with the job. Most of us probably fit somewhere<br />

between these extremes, and have developed our own strategies for<br />

coping with the ups and downs of our everyday work; there will be few<br />

of us who have not accumulated a private, personal collection of<br />

memories that will always remain with us.<br />

When we spend so much of our time caring for patients who are<br />

critically ill because of accidents, bad luck or complications, do we<br />

really walk away as unscathed as we would like to believe? I suspect<br />

not. Most colleagues (if persuaded to discuss this largely ‘no go’<br />

area) admit to having rather distorted perspectives about things<br />

like accident risks, family health and life expectancy, and many<br />

acknowledge that these do affect their worries about everyday<br />

activities. It seems that we cope in different ways – from fastidious<br />

fitness training to music-making, skiing to scuba diving. It also seems<br />

clear that the peer support from working in a cohesive team plays an<br />

important part in attenuating the effects of difficult days. Within the<br />

‘bell curve’ distribution of personalities, it is perhaps inevitable that<br />

there will be some who will be at the vulnerable end, and we can only<br />

speculate on what influences the development of depressive illness<br />

that leads them to end their life – but it seems clear that we should all<br />

do everything that we can to identify colleagues who may be at risk,<br />

and to help them in any way that we can.<br />

Two articles in this edition provide us with retrospective commentary<br />

on other, tragic unexpected events, with an analysis of the clinical<br />

lessons learned from the <strong>July</strong> London bombings and of the huge<br />

practical difficulties that had to be tackled by volunteers in the<br />

aftermath of the Pakistan Earthquake. Those of you who attended<br />

the excellent Gilston Lecture at the Spring Meeting will have been<br />

impressed by the science that underpins the concept of intensive<br />

insulin therapy, and two articles are included which focus on its<br />

implementation and potential complications in intensive care practice.<br />

Also included is an analysis of the implications of the latest legal ruling<br />

in the Baby MB case, a thought-provoking perspective on organ<br />

donation, updates on PVL staphylococcal infection, the ACUTE<br />

initiative, and medical device malfunction. And for those of you who<br />

may be considering taking on the role of Clinical Director, Wood and<br />

Trees offer some advice that you may wish to consider!<br />

B Taylor<br />

bruce.taylor@porthosp.nhs.uk<br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

4<br />

Report<br />

President’s Report<br />

President -<br />

Anna Batchelor<br />

It’s hard to believe that a year has gone by already.<br />

This is a great job and I am really enjoying it, but<br />

it’s hard work! I am writing this in a hotel room in<br />

London, having got the 0718 train this morning<br />

from Newcastle and attended the Critical <strong>Care</strong><br />

Stakeholders forum (CCSF) meeting, after which<br />

I had tea and a “catch up” with Keith Young from<br />

the Department of Health and Jane Eddleston,<br />

the Department advisor for Critical <strong>Care</strong>. When<br />

ensconced in my room (I am rapidly becoming an<br />

expert on the hotels of Bloomsbury) I did about 2<br />

hours of electronic “paper work” and dealing with<br />

emails before getting down to writing this report.<br />

Tomorrow I am having breakfast with Kathy Rowan<br />

from ICNARC, followed at 1030 by chairing the<br />

Education and Competence group for the assistant<br />

critical care practitioners’ stream of New Ways of<br />

Working in Critical <strong>Care</strong>, and late afternoon hoping<br />

to make the Royal College of Anaesthetists Critical<br />

<strong>Care</strong> Committee. With luck and a following wind I<br />

will get the 1700 train and be home about 2015 just<br />

in time to put my baby to bed. I will have to miss the<br />

Royal College of Physicians Critical <strong>Care</strong> Committee<br />

meeting tomorrow morning unless I can clone myself<br />

before then. Cloning would actually be very useful<br />

because if I had stayed in Newcastle today I would<br />

have done a 0900 to 2100 day in theatre which of<br />

course has been left to my colleagues back at the<br />

ranch. Last week had just 1 day away and next<br />

week is similar, but the following one I am away 4<br />

days. <strong>The</strong> representation work increases year on<br />

year, a reflection of the value placed on the <strong>Society</strong>’s<br />

advocatory role for Critical <strong>Care</strong> clinicians. You<br />

could ask why more is not done on email, but<br />

sometimes meeting face to face just gets the job<br />

done quicker and sometimes interesting things<br />

happen at meetings - but more of that later.<br />

Saxon Ridley has now left Council and Jane Harper<br />

has been elected to fill my former place. I am<br />

particularly pleased that I have replaced by another<br />

woman - for some reason very few stand for<br />

election. I am sure Jane will be a useful addition<br />

to the <strong>Society</strong> and as Chair of the Network Medical<br />

Leads will bring the strands back together which I<br />

hope will lead to a stronger force for Critical <strong>Care</strong>.<br />

At the CCSF today we heard that several networks<br />

are struggling to find funding and some have just<br />

ceased to be. This is a great pity as networking is<br />

something intensivists do well and the benefits are<br />

there for commissioners to see if only they would<br />

take the trouble to look. I very much hope that the<br />

combined efforts of the <strong>Society</strong>, the Medical Leads<br />

and the CCSF may be able to help these networks<br />

get back up and running.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Spring meeting in Harrogate went well, and we<br />

still have the Focus meeting on Transplantation, the<br />

Trainees’ Meeting and State of the Art to come. This<br />

year we are also introducing some small seminars in<br />

the new College on Clinical Excellence Awards,<br />

Education and Management, so look out for those<br />

too. We are very aware that access to study leave<br />

may be less generous than previously and that you<br />

need good value from the meetings you do attend,<br />

so I hope the <strong>Society</strong> can deliver this.<br />

<strong>The</strong> National Burn <strong>Care</strong> Review is coming to a<br />

conclusion and Specialised Commissioners are<br />

working with providers to fit their local service into<br />

the Centre/Unit/Facility model. I was concerned to<br />

see that there were apparently less beds for burns<br />

critical care in the Jan 06 KH03a compared to Jan<br />

05, and we must guard against the possibility of<br />

having less provision for burn critical care at the end<br />

of this review than we had at the beginning. I would<br />

be keen to hear of any problems colleagues have<br />

experienced.<br />

<strong>The</strong> New Ways of Working Programme continues<br />

and the Advanced Critical <strong>Care</strong> Practitioner<br />

Education and Competence Framework which is<br />

currently going through the Government ‘Gateway’<br />

should be available in both hard copy and<br />

electronically very soon. I hope you will look at it<br />

and feed back. I strongly believe we need to look<br />

towards practitioners who are appropriately trained<br />

and supervised helping us with the service delivery<br />

gap which will be left by Modernising Medical<br />

<strong>Care</strong>ers and the EWTD. As with many things with<br />

the DH, there is of course no money to continue the<br />

programme and fund second wave pilots. I hope the<br />

framework is strong enough to enable the production<br />

of a high quality transferable practitioner workforce.<br />

Having completed that we are now working on the<br />

Assistant Practitioner documentation and this should<br />

be available in the late summer.<br />

We are hoping that NICE will be able to take on<br />

“<strong>The</strong> <strong>Care</strong> of the Unexpectedly Acutely Ill Patient<br />

in Hospital” as a fast track programme. <strong>The</strong> initial<br />

vibes are good and we await ministerial approval.<br />

NICE are a powerful body whose edicts must be<br />

followed. Unfortunately we cannot tell them what to<br />

put in their guidance but we hope that the results of<br />

the NCEPOD report along with the considerable<br />

amount of expertise now available will result in a<br />

process that leads to benefits for patients.<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Report continued 5<br />

<strong>The</strong> Critical <strong>Care</strong> Contingency Planning Group<br />

continues to work on the complicated issues that<br />

may arise from an unexpected sudden increase in<br />

demand for intensive care beds, and is due to<br />

produce the first draft guidance in the near future.<br />

<strong>The</strong> group wishes it to be clear that this should be<br />

regarded as ‘work in progress’ and that feedback<br />

and suggestions for future amendments will be<br />

welcomed and encouraged.<br />

Professor David Menon continues to do excellent<br />

work representing the specialty concerning the<br />

Human Tissue Act, Mental Capacity Act, the Clinical<br />

Trials Directive, and the Data Protection Act. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

are very complex documents and I am grateful to<br />

David for his diligence and expertise in guiding us<br />

through these issues.<br />

At the beginning I said sometimes meetings can be<br />

interesting... ...last week’s away day proved to be<br />

very unexpectedly so. You may have heard of Skills<br />

for Health, a Sector Skills Council for Health - one<br />

of 27 such projects covering the whole UK economy<br />

(that’s plumbers, electricians and just about<br />

everyone with the possible exception of politicians).<br />

This body have been in existence for some time,<br />

writing competences (sic) for all health care workers<br />

including doctors. It was clear at the meeting that<br />

many people had just woken up to the existence of<br />

this organisation and they were not too impressed<br />

with the product. You may wish to look at the<br />

website http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/. I would<br />

be very grateful for feedback which I can add to that<br />

I have already provided. For those of you who<br />

cannot face this I will just tell you there are 92<br />

competences for Emergency Urgent and Scheduled<br />

<strong>Care</strong>, of which giving an anaesthetic is one and<br />

taking a blood sample is another. Quite why out<br />

of only 92, removing organs deserves a whole<br />

competency I will leave you to guess.<br />

So that’s it, a few days in the life of the ICS<br />

President, till the next issue TTFN.<br />

A Batchelor<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

6<br />

Meeting Report<br />

Harrogate ICS Spring Meeting<br />

<strong>2006</strong> Report<br />

T Jackson<br />

Harrogate was once again chosen to host the<br />

Spring ICS meeting this year. Having enjoyed the<br />

successful SKINT meeting, delegates gathered amid<br />

the decidedly changeable weather for the two day<br />

conference. A packed programme boasted parallel<br />

sessions with such diverse themes as trauma and<br />

climate change (ironic in the context of the change<br />

of weather from Monday to Tuesday!) and promised<br />

an array of expert speakers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Harrogate International Centre has developed<br />

since the last ICS meeting, with the addition a year<br />

ago of the Queens Suite adding to the flexible<br />

conference facilities. <strong>The</strong> first session here centred<br />

on trauma, starting with Prof Monty Mythen’s<br />

presentation of the pitfalls in evidence for volume<br />

resuscitation strategies based on certain well-quoted<br />

trials. <strong>The</strong> general consensus was carried into the<br />

questions, namely that minimal resuscitation should<br />

not be mistakenly interpreted as under-resuscitation.<br />

Prof Pete Giannoudis developed a comprehensive<br />

journey through the genetic basis of trauma<br />

responses, from the history of trauma management<br />

strategies to the future expectations of genetic<br />

markers of inflammatory responses. <strong>The</strong> session<br />

was concluded with a poignant reminder of the<br />

recent London terrorist bombs from Dr Hugh<br />

Montgomery, with the chilling message that many<br />

of our colleagues in the capital knew a terrorist<br />

attack was a certainty, and the place that drills and<br />

preparation played in the response to those attacks.<br />

Having watched the events unfold in the media that<br />

day, as many of us will remember, it was fascinating<br />

to hear first hand experience of the dynamics of<br />

casualty flows and intensive care activity at such a<br />

testing time.<br />

<strong>The</strong> parallel session in the main auditorium<br />

concerned outreach issues, with presentations on<br />

the lack of evidence for efficacy of outreach in the<br />

light of the antipodean MERIT study, the spectrum<br />

of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the ICU setting<br />

and some potential avenues for impacting on these<br />

difficult conditions, and discussion of the commonly<br />

applied ‘track and trigger’ scoring systems applied<br />

to patients at risk of critical illness.<br />

<strong>The</strong> refreshment break provided the first<br />

opportunity to view the range of industry exhibitors,<br />

although there was some debate as to who would<br />

pluck up courage to visit the rectal tube vendors<br />

with confidence!<br />

<strong>The</strong> second session of the day fell to a choice of<br />

matters nephrological or scanning the horizon for<br />

areas of forthcoming impact on the critical care<br />

world. <strong>The</strong> former, began with a talk from Dr<br />

Andrew Davenport concerning the haemodynamic<br />

instability associated with renal replacement therapy.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were some useful insights into methods of<br />

minimising this potentially serious complication.<br />

Dr Andy Lewington from Leeds spoke on the<br />

interplay between nephrologists and intensivists in<br />

the management of the critically ill patient with renal<br />

failure, although it was clear that not all shared his<br />

experience of joint care. Following on from this was<br />

Prof Didier Payen from Paris presenting his work on<br />

whether early renal replacement has any impact on<br />

the progression of organ dysfunction in sepsis.<br />

On the background of various theories why<br />

haemofiltration might be effective was clear<br />

evidence to the contrary, however he ended by<br />

suggesting that high-volume filtration may offer<br />

some as yet unproven benefit.<br />

Lunch was followed by an intriguing look at how<br />

climate change may affect the spectrum of infectious<br />

diseases presenting to UK ICUs. This was put into<br />

context by a talk from Prof Ken Carslaw from Leeds<br />

University’s school of Earth and Environment,<br />

detailing how the evidence for global warming has<br />

developed over the years, and predictions of how<br />

our impact on the climate is likely to progress. With<br />

increasing coverage of this field in the media, it was<br />

interesting to hear expert opinion on a politically ‘hot’<br />

topic. Following this, Dr Philip Stanley presented<br />

illustrative cases of diseases associated with foreign<br />

travel which may already necessitate ICU admission<br />

in a small group of individuals, a theme which was<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Meeting Report continued 7<br />

developed by Prof Jon Cohen, who discussed<br />

reasons why infectious diseases with which we are<br />

unfamiliar may become more commonplace in the<br />

face of a climate more associated with North African<br />

countries. He used the examples of West Nile virus<br />

and Hantavirus to illustrate how climate change can<br />

have a direct impact on disease presentation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> highlight of the afternoon was the Gilston<br />

Lecture, where Prof Greet Van den Berghe<br />

presented a very comprehensive account of her<br />

compelling research into glycaemic control in<br />

intensive care.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was a noticeable paucity of delegates at the<br />

pre-conference coffee on day two. I’m not sure if<br />

this was related to over-indulgence at the dinner<br />

dance the night before, or to casualties of the<br />

fun-run earlier that morning.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Fun Run - raring to go...!<br />

Day two promised further interesting topics, and I<br />

began to wish I could clone myself and attend both<br />

parallel sessions. <strong>The</strong> aspects of training and<br />

revalidation were received well, particularly in the<br />

current climate of modernising medical careers<br />

and contract issues. However, I elected to join the<br />

neurosciences session. Dr Peter Andrews<br />

presented an overview of potential advances in<br />

neurocritical care, including the disappointing results<br />

of several important trials, suggesting alternative<br />

ways of assessing outcome to improve the yield of<br />

trials in the future. He also concentrated on the role<br />

of decompressive craniectomy in the management of<br />

traumatic brain injury, and ended with outlines of<br />

agents which may show some promise, including<br />

statins which are being assessed for use in<br />

vasospasm related to subarachnoid haemorrhage.<br />

Professor Carl Hendrik Nordstrom presented the<br />

theory and practice of the Lund approach to<br />

managing traumatic brain injury, which differs<br />

from the standard North American teaching on<br />

maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure. He<br />

described the protocol for manipulating capillary<br />

hydrostatic pressure, including the use of metoprolol<br />

and clonidine accepting cerebral perfusion pressures<br />

down to 50mmHg. It was clear from the lively<br />

discussion which was initiated (but sadly not<br />

concluded due to time constraints) that neither Lund<br />

nor North American approaches suit all brain-injured<br />

patients. <strong>The</strong> session was completed by Dr Steve<br />

Wilson with a round-up of the evidence base (or lack<br />

thereof) for various elements of the management<br />

of traumatic brain injury. <strong>The</strong> most compelling<br />

evidence seemed to be from the TARN database<br />

study suggesting significant reduction in mortality in<br />

patients managed in a neurosurgical centre,<br />

although Dr Wilson presented some obvious<br />

caveats.<br />

Next, I attended the session on trainee issues.<br />

This caught my eye largely for the echo talk, and<br />

didn’t disappoint. It was heartening to hear Dr<br />

Robert Orme talk of his quest to become trained in<br />

echocardiography, although this personal account<br />

also reinforced what I and many colleagues have<br />

found, which is that it isn’t easy to acquire the<br />

necessary exposure to train and then remain<br />

validated in such techniques. Dr Orme also<br />

imparted some useful resources for anyone<br />

interested in achieving echo competence. This<br />

was followed by an interesting presentation by Mrs<br />

Carole Boulanger detailing her metamorphosis from<br />

experienced intensive care sister to advanced critical<br />

care practitioner. It is clear both from her talk and<br />

some of the questions that there is some unease at<br />

the origin of these new roles from various quarters,<br />

but as manpower issues become more prevalent,<br />

ACCPs may well become more commonplace.<br />

Delegates assemble in the lecture area<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

8<br />

Meeting Report continued<br />

<strong>The</strong>re then followed a pair of lunchtime symposia.<br />

I was surprised that nobody seemed to adopt the<br />

Latin derivation of this term (a drinking party) and<br />

instead we all tucked into our packed lunches with<br />

as little rustling as possible, so as to hear the<br />

industry sponsored presentations. <strong>The</strong> Queen’s<br />

Suite auditorium hosted two presentations regarding<br />

remifentanil based sedation regimes. Firstly, Dr Atul<br />

Kapila described the experience in Reading of the<br />

introduction of a sedation protocol and subsequent<br />

audit cycles, highlighting the issues surrounding<br />

education for the nursing staff. This was followed by<br />

Dr Wolfram Wilhelm from Lunen in Germany, who<br />

presented his unit’s experience of more widespread<br />

use of remifentanil in ICU. In the parallel lunchtime<br />

session Dr Duncan Wyncoll summarised the results<br />

of the XPRESS study, an investigation into the<br />

administration of Activated Protein C with or without<br />

heparin.<br />

into the breach at very short notice, describing the<br />

‘Lo-Trach’ endotracheal tube and its role in<br />

minimising the impact of ventilator associated<br />

pneumonia, for which he presented a compelling<br />

argument. Following this, Prof Van den Berghe<br />

again took to the platform to reprise her glycaemic<br />

control research, this time including discussion of<br />

some of the studies which have disagreed with her<br />

work, and answering some of the criticisms that<br />

have been levelled at it. Finally, Dr Sapsford also<br />

returned, to discuss the myths and developments in<br />

arrhythmia management, centring on various rhythm<br />

disturbances and the emerging role of<br />

radiofrequency ablation techniques to provide more<br />

long-term relief. Of more relevance to critical care<br />

were his discussion of atrial fibrillation and the<br />

evolution of the rate versus rhythm control debate,<br />

which currently favours the former (probably!).<br />

<strong>The</strong> meeting was a resounding success with some<br />

very stimulating presentations from a wide range of<br />

nationally and internationally renowned speakers.<br />

Thanks must go to Prof Mark Bellamy and Ms Judith<br />

Thornton for their work in developing the programme<br />

and also for the hard work put in by the ICS<br />

secretariat and meetings committee. Here’s to a<br />

repeat performance next year at Bournemouth!<br />

As usual, the poster presentations attracted lots of interest<br />

After lunch, there were parallel sessions on<br />

cardiology and IT in critical care. <strong>The</strong> cardiology<br />

session began with Echoardiography in ICU<br />

presented by Dr Sean Bennett with a<br />

complementary view to Dr Orme earlier; he<br />

presented several clinical examples of how echo<br />

diagnosis can affect ICU management. <strong>The</strong> second<br />

presentation was from Dr Rob Sapsford regarding<br />

the management of acute coronary syndromes,<br />

and brought together some of the changes in<br />

nomenclature and investigations which have evolved<br />

over the last few years. Rounding off the session<br />

was a presentation by Prof Alistair Hall on<br />

biomarkers of coronary disease, introducing the<br />

markers which can further refine the management of<br />

patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes,<br />

and the future for multi-marker profiling.<br />

<strong>The</strong> final session of the day centred on myths<br />

and new developments in critical care. Dr Duncan<br />

Wyncoll performed magnificently having stepped<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Meeting Report continued 9<br />

Exhibition Report<br />

M Moore<br />

Harrogate International Centre held this year’s<br />

Spring <strong>2006</strong> Conference on 22 nd - 24 th May, which<br />

included the Skills for Intensivists Workshops and<br />

the Annual Spring <strong>2006</strong> Meeting, successfully filling<br />

the trade hall with 49 exhibitors with a mixture of<br />

Corporate, Company and non industry members.<br />

After hours of build up, constructing the stands for<br />

the exhibition, we finally produced a trade hall with<br />

some amazing purpose built stands. AstraZenca’s<br />

stand was one of the impressive designs that<br />

appeared very appealing to the delegates with<br />

interactive technology and a modernised style.<br />

Although the weather was clearly not on our side<br />

throughout, delegates still arrived first thing to attend<br />

this year’s event. Everything ran smoothly as<br />

delegates weaved through the whole venue covering<br />

the exhibition hall and both main sessions.<br />

Tuesday evening mellowed down to the sound of<br />

Jazz at our Annual Dinner and Dance accompanied<br />

by appetising food and drink and a lively atmosphere<br />

on the dance floor.<br />

It was a bright and early start on Wednesday<br />

morning for those who took part in the <strong>Intensive</strong><br />

<strong>Care</strong> Foundation Fun Run around the muddy fields<br />

of Harrogate. <strong>The</strong>re was just enough time for a<br />

quick change, then it was back to the Centre for the<br />

final day of educational and research sessions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ICS would like to thank all exhibitors and<br />

sponsors for contributing to this event and their<br />

continuing support throughout the years. We greatly<br />

appreciate the involvement from our Industry<br />

Members and look forward to welcoming new<br />

associates to our Corporate and Company<br />

Membership Schemes.<br />

Thank you to the following exhibitors:<br />

Abbott Point of <strong>Care</strong><br />

Anmedic UK Ltd<br />

Arrow International UK Ltd<br />

AstraZeneca UK Ltd<br />

B. Braun Medical Ltd<br />

Beaver Medical<br />

BOC Medical Plc<br />

Cardiac Services<br />

Codan Ltd<br />

ConvaTec Ltd<br />

Cook UK<br />

Delta Surgical Ltd<br />

DOT Medical<br />

Dräger Medical UK Ltd<br />

Edwards Lifesciences Ltd<br />

Eli Lilly & Co Ltd<br />

Eumedica Pharmaceuticals<br />

Fresenius Kabi Ltd<br />

Fresenius Medical <strong>Care</strong><br />

Fukuda Denshi UK<br />

Gambro Hospal Ltd<br />

GE Healthcare<br />

Gilead Sciences Ltd<br />

GlaxoSmithKline Ltd<br />

Henleys Medical Supplies Ltd<br />

IMPACT<br />

Inspiration Healthcare Ltd<br />

Johnson & Johnson Wound Management<br />

Kapitex Healthcare Ltd<br />

Lidco Ltd<br />

Maquet Ltd<br />

Norvartis Medical Nutrition<br />

Novo Nordisk Ltd<br />

Pfizer Ltd<br />

Pulsion Medical<br />

Respironics UK Ltd<br />

Roche Diagnostics Ltd<br />

SLE Ltd<br />

Smiths Medical<br />

SonoSite Ltd<br />

Spacelabs Medical UK Ltd<br />

Teleflex Medical Systems Ltd<br />

<strong>The</strong> CESAR Trial<br />

TracMan Trial<br />

Trumpf Medical Systems Ltd<br />

Viasys Healthcare<br />

Vital Signs Ltd<br />

Wisepress Ltd<br />

Zeneus Pharma Ltd<br />

M Moore<br />

Events & Marketing Administrator<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

10<br />

Meeting Report continued<br />

Spring <strong>2006</strong> Clinical Practice Poster Presentation Winner<br />

Congratulations to:<br />

Dr Rachid Berair and Dr Michael Lim<br />

Audit on physician prescription of sedation scores in mechanically ventilated patients<br />

Spring <strong>2006</strong> Research Poster Presentation Winner<br />

Congratulations to:<br />

Dr Elaine Harrison, Dr Samuel Pambakian, Dr Justin Woods and Dr William Fellingham<br />

Comparison between pulmonary artery catheter and Vigileo – FloTrac<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong><br />

Annual Spring <strong>2006</strong> Meeting<br />

Delegate Badge Prize Draw Winner<br />

Congratulations to Dr Paul Knight from<br />

Calderdale Royal Hospital, whose badge was<br />

drawn out to receive the £25 book token.<br />

We thank all those delegates who return their<br />

badges at the end of each conference.<br />

This ensures the badge holders are re-used at<br />

future events and helps to keep costs down.<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Meeting Report continued 11<br />

SKINT - Skills for Intensivist Workshops<br />

D Goldhill<br />

<strong>The</strong> workshops have now been running for two<br />

years and have all been held in conjunction with<br />

one of the ICS meetings. <strong>The</strong> equipment-based<br />

workshops are designed to be practical hands-on<br />

sessions providing an opportunity to work with a<br />

range of equipment and to get first-hand advice<br />

from experts.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ultrasound-guided vascular access workshop<br />

At the recent conference in Harrogate four<br />

workshops were held. <strong>The</strong>y were;<br />

1. Advanced ventilation:<br />

This year the workshops was expanded and<br />

started in the morning and ran until late afternoon.<br />

Topics covered included non-invasive ventilation,<br />

COPD/asthma, automated weaning, prone<br />

entilation, lung recruitment and oscillation. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

was the opportunity to work with machines from<br />

Drager, Respironics. Maquet, Viasys and GE.<br />

2. Percutaneous tracheostomy:<br />

This popular workshop was based around<br />

Cook and Portex kits with key lectures and<br />

demonstrations using models, bronchoscopes<br />

and the tracheostomy kits themselves.<br />

<strong>The</strong> workshops took place on Monday 23 rd May,<br />

the day before the main conference. Most places<br />

were taken and feedback from all of them has been<br />

excellent. As well as these workshops, Intracranial<br />

Pressure Monitoring has been run several times.<br />

Future planned workshops are on Non-invasive<br />

Cardiac Output Monitoring and Echocardiography.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir success is due to three things. Firstly the<br />

enthusiasm and hard work of individuals who<br />

devised and organised the individual workshops.<br />

For Ventilation this was Peter Macnaughton, for<br />

Percutaneous Tracheostomy Alf Shearer, for<br />

Ultrasound Andy<br />

Bodenham, for Intracranial<br />

Pressure Monitoring Carl<br />

Waldmann and for the<br />

PBL Monty Mythen.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se individuals have<br />

been joined by a team of<br />

helpers who have freely<br />

given of their time and<br />

expertise for little reward.<br />

<strong>The</strong> percutaneous<br />

tracheostomy workshop<br />

<strong>The</strong> final element in the<br />

package is the support<br />

of industry who have<br />

supplied the equipment<br />

and educational materials.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se workshops are a superb opportunity to learn<br />

or revise some essential skills, and to play with the<br />

necessary toys. <strong>The</strong>y will be run again. If you want<br />

to help with any of the current workshops, or if you<br />

have ideas for workshops you would like to run,<br />

please contact the ICS.<br />

D Goldhill<br />

SKINT_Meister<br />

3. Ultrasound-guided vascular access:<br />

This workshop has been run on several previous<br />

occasions. ‘Phantoms’ and volunteers allowed<br />

the participants to get excellent training in<br />

ultrasound anatomy, needle visualisation and<br />

techniques for vascular access. <strong>The</strong> session<br />

ended with an introduction to echocardiography.<br />

4. Problem-based clinical scenarios (PBL):<br />

This was a new innovation consisting of an<br />

interesting review of current sepsis treatment<br />

options followed by an interactive discussion of<br />

three case presentations. This was a marvellous<br />

opportunity to learn from experts about their<br />

approach to real clinical cases.<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

12<br />

Research & Development Update<br />

TracMan: Tracheostomy<br />

Management in Critical <strong>Care</strong><br />

Update<br />

Dear All,<br />

Over 60 <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Units (ICUs) around the UK are now collaborating in the TracMan Trial with a total of<br />

335 patients recruited (at 25 May). Terrific effort from the ICS community we think!<br />

Our top recruiting ICUs January to April <strong>2006</strong> are:<br />

Month<br />

Jan 06<br />

Feb 06<br />

Mar 06<br />

Apr 06<br />

Hospital and Lead Consultant/Nurse<br />

Whiston Hospital, Prescot (Dr R MacMillan)<br />

Southampton General Hospital (Dr T Woodcock & Mrs K de<br />

Courcy-Golder)<br />

Joint top recruiters:<br />

Derriford Hospital, Plymouth (Dr P D Macnaughton & Mrs N Donlin)<br />

St Thomas Hospital, London (Dr D Wyncoll & Mr T Sherry)<br />

Southampton (Dr T Woodcock & Mrs K de Courcy-Golder)<br />

Derriford Hospital, Plymouth (Dr P D Macnaughton & Mrs N Donlin)<br />

Our thanks go to these and all our collaborators for their efforts and enthusiasm! We are well on our way to<br />

addressing the important question concerning the timing of tracheostomy.<br />

If your ICU is not currently involved in TracMan and you would like to know more, please do not hesitate to<br />

contact me on Tel: 01865 857627, email: Lesley.morgan@nda.ox.ac.uk.<br />

Look forward to hearing from you!<br />

L Morgan<br />

TracMan Trial Manager<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Surveys & Audits 13<br />

Designated Consultants for the Inter-Hospital Transfer of<br />

Patients with Brain Injury: A Survey of Practice Among<br />

Neurosurgical Units in the UK and Ireland<br />

G Allen, P Farling, B A Mullan<br />

Summary<br />

In 1996 the Association of Anaesthetists of<br />

Great Britain and Ireland, in conjunction with the<br />

Neuroanaesthesia <strong>Society</strong>, produced a set of<br />

recommendations for the inter-hospital transfer of<br />

brain injured patients. Ten years on we surveyed<br />

neurosurgical units in the UK and Ireland to assess<br />

their compliance with the recommendations. Thirty<br />

three out of a possible 36 units participated in the<br />

survey, which revealed that a significant proportion<br />

of neurosurgical units still do not have a consultant<br />

with overall responsibility for standards relating to<br />

transfer. <strong>The</strong> presence of such a person would<br />

appear to facilitate audit and training and improve<br />

patient safety. Importantly, the infrastructure to<br />

support the role of the designated consultant is<br />

currently inadequate.<br />

Introduction<br />

In the UK moderate and severe head injuries<br />

have a yearly incidence of 15 per 100,000 of the<br />

population 1 . It has been estimated that 11,000<br />

inter-hospital transfers of critically ill patients may<br />

occur in a year 2 . Approximately 10% of these<br />

may be for isolated head injuries 3 . In 1996 the<br />

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain<br />

and Ireland (AAGBI), in conjunction with the<br />

Neuroanaesthesia <strong>Society</strong>, produced<br />

recommendations for the safe transfer of patients<br />

with brain injury 4 . An audit of the ability of UK<br />

hospitals to implement these recommendations<br />

was published in 1999 5 . It showed that many<br />

hospitals had responded to the guidelines and were<br />

attempting to implement them. However, it also<br />

concluded that designated consultants, with<br />

responsibility for overseeing the conduct of transfers<br />

and staff training, were not readily identifiable. It is<br />

now 10 years since the publication of the initial<br />

recommendations. A revised, up-to-date set, are<br />

due to be published this year. We therefore felt that<br />

it would be timely to undertake a survey of the<br />

neurosurgical units in the UK and Ireland to assess<br />

their current compliance with the appointment of<br />

lead clinicians responsible for inter-hospital<br />

transfers. <strong>The</strong> units also provided information on<br />

the education, training and audit activities related to<br />

neuro-transfers, and the local infrastructure in place<br />

to support these activities.<br />

Methods<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are 36 neurosurgical units in the UK and<br />

Ireland (Table 1). <strong>The</strong> Neuroanaesthesia <strong>Society</strong><br />

of Great Britain and Ireland (NASGBI) has a<br />

representative in each of these units. This<br />

representative was contacted and asked if they<br />

would participate in a telephone questionnaire<br />

survey at a time which was convenient. <strong>The</strong><br />

representative could delegate the questionnaire<br />

to a more appropriate consultant if applicable.<br />

A single investigator (GA) collected all the data.<br />

As Northern Ireland has a well-established regional<br />

critical care transport service, we also surveyed the<br />

district general hospitals (DGHs) in Northern Ireland<br />

with a functioning Emergency Department. <strong>The</strong> lead<br />

clinicians in the Departments of Anaesthesia at<br />

these hospitals were identified and their participation<br />

requested. A separate questionnaire was developed<br />

for the DGHs.<br />

Results<br />

Thirty three of the 36 neurosurgical units participated<br />

in the survey. Failure to achieve a 100% response<br />

rate was due to our inability to contact the<br />

appropriate NASGBI representative for that unit<br />

and to identify a suitable substitute.<br />

Seventeen units (52 %) had a designated consultant<br />

with overall responsibility for the inter-hospital<br />

transfer of head injured patients. Only 3 of these<br />

units (18 %) had this activity recognised in the<br />

consultant’s job plan. No units were able to identify<br />

specific budget allowances for the role of the<br />

designated consultant. Units involved in regional<br />

critical care transfer services did have separate<br />

funding arrangements for these activities. Three<br />

adult units (Table 1) are currently involved in the<br />

retrieval of head injured patients. In all cases this<br />

was by way of a general transfer service for the<br />

critically ill, which would on occasion transport<br />

head injured patients if the acuity of the situation<br />

permitted.<br />

A total of 16 units (49 %) were participating in formal<br />

education and training of junior medical staff<br />

involved in the transfer of head injured patients: 13<br />

of the 17 units (76 %) with a designated consultant,<br />

and 3 of the 16 units (19 %) without a designated<br />

consultant. Audit was performed at 27 units (82 %):<br />

13 of these units were regularly auditing transfers<br />

and 14 were auditing occasionally. All units with a<br />

designated consultant performed audit, whereas only<br />

10 of the 16 units without a designated consultant<br />

undertook audit (63%).<br />

Of the DGHs surveyed, 7 out of 11 hospitals<br />

participated in the survey (64% response rate).<br />

Only 1 of the hospitals (14 %) had a designated<br />

consultant. 2 hospitals audited their transfers (29%).<br />

All senior house officers in the Northern Ireland<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

14<br />

Surveys & Audits continued<br />

School of Anaesthesia receive formal lectures on<br />

inter-hospital transfer and on the management of<br />

head injured patients. <strong>The</strong> transfers were normally<br />

performed by consultants in 1 hospital (14 %), by<br />

senior house officers in 2 hospitals (29 %) and by<br />

specialist registrars in the remaining 4 hospitals (57<br />

%). On occasions all 7 hospitals had used the<br />

regional general critical care transfer service to<br />

transport acute head injuries. <strong>The</strong> decision to use<br />

the service or not was taken by the neurosurgeon<br />

on-call, and was determined by the perceived<br />

urgency of the situation. All 7 hospitals felt that<br />

regular formal feedback form the receiving<br />

neurosurgical unit would be helpful.<br />

Discussion<br />

Trauma services in the UK and Ireland are<br />

organised regionally. <strong>The</strong>refore patients with brain<br />

injury who require definitive treatment may have to<br />

be transferred from a receiving hospital to a<br />

neurosurgical unit. Many studies have shown that<br />

such transfers may be poorly conducted and hence<br />

patients may be exposed to secondary insults 6,7 .<br />

<strong>The</strong>se insults include raised intracranial pressure,<br />

hypotension, hypoxia, hypercapnea, hyperpyrexia<br />

and hyperglycaemia. <strong>The</strong> risk of secondary brain<br />

damage can be reduced if the transfer is of high<br />

quality and based on sound principles. In 1996<br />

the AAGBI and the NASGBI published a set of<br />

recommendations for the safe transfer of patients<br />

with acute head injuries to neurosurgical units 4 .<br />

One of the recommendations was that there should<br />

be designated consultants in the referring hospitals<br />

and the neurosurgical units with overall responsibility<br />

for transfers. It was envisaged that this individual<br />

would have an important role in the clinical<br />

management of transfers, the education and<br />

training of nursing and medical staff, and in<br />

auditing the quality of inter-hospital transfers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> recommendations also stated that trusts should<br />

recognise that appropriate time and funding is<br />

required to support these activities. Our survey<br />

has revealed that almost 10 years on from the<br />

publication of the recommendations a significant<br />

proportion of neurosurgical units still do not have a<br />

designated consultant. <strong>The</strong> figures were even more<br />

disappointing for the acute DGHs in Northern<br />

Ireland. In those units that could identify a<br />

designated consultant, it would appear that little<br />

recognition or support for the activity is being<br />

provided by the healthcare trusts. This situation<br />

is untenable for the future. Without adequate<br />

resources it is extremely difficult to have a good<br />

quality service. <strong>The</strong> activities of the designated<br />

consultants involve a substantial time commitment<br />

and should be reflected in their job plans.<br />

A survey by Knowles et al in 1999 5 revealed that<br />

many referring hospitals in the UK thought that the<br />

formation of transfer teams to transport severe<br />

head injuries would have some merit. Currently<br />

only 3 adult units are involved in the retrieval of<br />

head injured patients. However, they are all general<br />

transfer services for the critically ill and are not<br />

specific for neurotrauma. Given the clinical urgency<br />

of some brain injury transfers, even if it were<br />

possible to establish specific neuro-transfer teams,<br />

there would still be occasions where the referring<br />

hospital would have to undertake the transfer<br />

themselves. Transfer teams cannot absolve<br />

DGHs of all their transfer responsibilities. Indeed,<br />

education and training would become even more<br />

important for these hospitals if the frequency with<br />

which they performed inter-hospital transfers was<br />

reduced.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Many neurosurgical units, and possibly many<br />

peripheral hospitals, do not yet have a designated<br />

consultant with overall responsibility for the transfer<br />

of patients with brain injuries. Our results suggest<br />

that the presence of this consultant facilitates<br />

education, training and audit, all of which are<br />

crucial to improving the standards of transfer. <strong>The</strong><br />

infrastructure to support the designated consultant<br />

is currently poor, with few units recognizing the role<br />

in the consultant’s job plan. Urgent attention is<br />

required to rectify this situation and future healthcare<br />

planners need to be made aware of the necessary<br />

resource implications.<br />

G Allen a , P Farling b , BA Mullan b<br />

a. Specialist Registrar<br />

b. Consultant, Department of Anaesthesia &<br />

<strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Medicine, <strong>The</strong> Royal Group of<br />

Hospitals, Grosvenor Road, Belfast, BT12 6BA.<br />

References<br />

1. Jennett B, MacMillan R. Epidemiology of head injury. Br Med J<br />

(Clin Res Ed). 1981;10: 101-4.<br />

2. <strong>Intensive</strong> care society. Guidelines for transport of the critically ill<br />

adult. ICS 1997.<br />

3. McGinn GH, MacKenzie RE, Donelly JA, Smith EA, Runcie<br />

CJ.Interhospital transfer of the critically ill trauma patient: the<br />

potential role of a specialist transport team in a trauma system.<br />

J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13:90-2.<br />

4. Jenkinson JL, Saunders DA, Wallace PGM, et al.<br />

Recommendations for the transfer of patients with acute head<br />

injuries to neurosurgical units. AAGBI. 1996<br />

5. Knowles PR, Bryden DC, Kishen R, Gwinutt CL. Meeting the<br />

standards for interhospital transfer of adults with severe brain<br />

injury in the United Kingdom. Anaesthesia 1999; 54: 280 – 283.<br />

6. Gentleman D, Jennett B. Hazards of inter hospital transfer of<br />

comatose head-injured patients. Lancet 1981; 2: 853 – 855.<br />

7. Vyvyan HAL, Kee S & Bristow A. A survey of secondary<br />

transfers of head injured patients in the south of England.<br />

Anaesthesia 1991; 46: 728-731.<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Surveys & Audits continued 15<br />

Table 1<br />

List of neurotrauma centers in the UK and Ireland.<br />

* Units with general critical care transfer services which occasionally transfer acute head injuries<br />

Aberdeen Dublin * Nottingham<br />

Atkinson Morley Dundee Oldchurch<br />

Barts & <strong>The</strong> London Edinburgh Oxford<br />

Belfast * Glasgow * Plymouth<br />

Birmingham Haywards Heath Preston<br />

Birmingham Child Hull Queen Square<br />

Bristol Kings Royal Free<br />

Cambridge Leeds Sheffield<br />

Cardiff Liverpool Southampton<br />

Charing Cross Manchester Stoke<br />

Cork Middlesbrough Swansea<br />

Coventry Newcastle Great Ormond St<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

16<br />

Surveys & Audits continued<br />

Tight Glycaemic Control in Scottish<br />

<strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Units<br />

E S Jack, M J E Neil<br />

Abstract<br />

Recent work has shown a mortality benefit in<br />

critically ill patients when hyperglycaemia is<br />

prevented. We performed a telephone survey of<br />

all ICUs in Scotland to identify methods of glucose<br />

control, their ability to achieve target ranges, and<br />

any related audit processes. In 23 of 26 adult ICUs<br />

blood glucose is controlled by formalised insulin<br />

protocols, mostly (19/26) similar to that described by<br />

Van Den Berghe. Few units are auditing the quality<br />

of this inexpensive and effective intervention.<br />

Keywords: Insulin; normoglycaemia; critical illness<br />

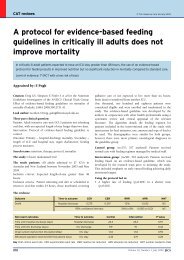

Figure 1: Methods of controlling normoglycaemia<br />

Introduction<br />

It has long been recognised that hyperglycaemia is<br />

associated with increased mortality in a variety of<br />

critical illnesses, e.g. acute myocardial infarction 1 ,<br />

stroke 2 and trauma 3 . Recent evidence has shown<br />

a mortality benefit in general intensive care patients<br />

by using insulin protocols to gain and maintain tight<br />

normoglycaemia 4,5 .<br />

Aims<br />

Our three primary aims were to establish:<br />

1. <strong>The</strong> methods of controlling blood glucose in use in<br />

Scottish ICUs.<br />

2. <strong>The</strong> blood glucose target ranges set by individual<br />

units.<br />

3. Whether target blood glucose levels are achieved<br />

and the audit processes used to measure this.<br />

ICU units<br />

Beds<br />

Rigid Protocol 19 145<br />

Individual approach 4 25<br />

Sliding scale 3 16<br />

Target Ranges<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a considerable variation in the target range<br />

adopted by units. Of 23 units (91.4% beds) using a<br />

target range (rigid protocol or individualised system)<br />

the majority [19 units, 134 beds (78.8%)] set a<br />

lower limit of

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Surveys & Audits continued 17<br />

Figure 3: ‘Tightness’ targeted<br />

Range (mmol.l -1 ) <strong>Number</strong> of units Beds<br />

1.5 –1.9 4 26<br />

2 – 2.4 8 60<br />

2.5 – 2.9 4 47<br />

3 – 3.4 3 16<br />

3.5 – 3.9 3 17<br />

4 1 4<br />

Audit of control<br />

Only 5 out of 26 (19%) units were aware of recent or<br />

ongoing audit of glycaemic control. All of these were<br />

units that had instigated a rigid protocol of control.<br />

Figure 4: Audit or survey of degree of control<br />

<strong>The</strong> remaining units had no observational study<br />

done within the previous 12 months, or if one had<br />

been performed its results had not been published<br />

within that unit.<br />

Discussion<br />

General intensive care has seen some significant<br />

advances over the recent past, including the first<br />

large scale randomised controlled trials involving<br />

the sickest of patients. This research has led the<br />

adoption of interventions proven to reduce<br />

mortality and morbidity, e.g. ARDSnet protocol for<br />

ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome 6 ,<br />

recombinant activated protein C for sepsis 7 , low<br />

dose corticosteroids for inotrope-dependent<br />

sepsis-related circulatory failure 8 , and maintenance<br />

of tight control of normoglycaemia with insulin 4 .<br />

Many of these have been integrated in the<br />

international ‘Surviving Sepsis Campaign’ 9 . <strong>The</strong><br />

acceptance and implementation of this evidence by<br />

the majority (23/26, 91.4% of beds) of Scottish units<br />

is encouraging. <strong>The</strong> absence of published evidence<br />

on the benefits of a rigid protocol versus an<br />

individualised daily scale limits conclusions about<br />

the decision to favour differing methods of glucose<br />

control.<br />

Target Ranges<br />

<strong>The</strong> wide variety of ranges of glucose concentration<br />

reported to be beneficial to patients is reflected in<br />

Scottish critical care practice. <strong>The</strong>re are significant<br />

variations in both the absolute limits set and the<br />

‘tightness’ of the range, often arising as a result of<br />

alterations made during implementation of protocols.<br />

Although these variations restrict comparison of the<br />

degree of control, the fact that 4 units set tolerance<br />

ranges of less than 2mmol.l -1 between upper and<br />

lower limits suggests that very tight control of<br />

acceptable glucose levels is practicable. Resistance<br />

to using tight limits has centred on the possibility of<br />

overt hypoglycaemia, but with good implementation<br />

this would seem avoidable.<br />

Audit<br />

In the absence of reliable audit of the<br />

implementation of this intervention, and only a<br />

minority of units (5 out of 26) appearing to<br />

disseminate information on results, concern must<br />

exist about overall achievement of tight glycaemic<br />

control. Although medical students, trainees or<br />

nurses may have indeed been diligently collecting<br />

data and performing small scale surveys, without the<br />

dissemination of such information to the wider staff<br />

progress is inevitably limited. It is the responsibility<br />

of all units to audit how well they are achieving their<br />

target levels (no matter which range they are using),<br />

and to keep all involved workers informed about the<br />

results, so that they can attempt to constantly<br />

improve. Our survey suggested that only one unit<br />

re-audited levels of control on a month-to-month<br />

basis; their control levels were up to 80% of all<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

18<br />

Surveys & Audits continued<br />

glucose results being within their set range (a very<br />

tight range of only 1.7mmol.l -1 ). Only 5 of the 26<br />

units had recollection of a survey/audit being<br />

completed within the previous12 months, with<br />

control levels ranging from 55% to 85%. This would<br />

seem to indicate scope for further improvements in<br />

achieving targets, and that very tight ranges can be<br />

applied in a general intensive care unit.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Most ICUs (23 of 26, 91.4% of beds) in Scotland<br />

use formalised approaches to maintaining<br />

normoglycaemia, with only 3 units (8.6% of beds)<br />

having no formal control mechanism. Discrepancies<br />

were identified in the definitions of normoglycaemia<br />

as well as the tolerance range (i.e. between 1.5 &<br />

4mmol.l -1 ) accepted. Although there is scope for<br />

improving the audit of glycaemic control within<br />

Scottish ICUs, the practice of tight control has to be<br />

seen in the wider context of overall intensive care.<br />

E S Jack a , M J E Neil b<br />

a. SpR <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Unit, Victoria Infirmary,<br />

Glasgow. G42 9TY. 0141 201 5320<br />

correspondence to ewanwendy@supanet.com<br />

b. SpR Department of Anaesthesia, Ninewells<br />

Hospital, Dundee. 01382 60111<br />

References<br />

1. Malmberg K, Ryden L, Hamsten A, et al. Effects of insulin<br />

treatment on cause-specific one-year mortality and morbidity<br />

in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. DIGAMI<br />

(Diabetes Insulin-Glucose in Acute Myocardial Infarction) Study<br />

Group. Eur Heart J 1996; 17: 1337–1344<br />

2. Scott, J. F.; Gray, C. S.; O'Connell, J. E.; Alberti, K. G. M. M.<br />

Glucose and insulin therapy in acute stroke; why delay further?<br />

Qjm 1998; 91: 511-515<br />

3. Laird AM. Miller PR. Kilgo PD. Meredith JW. Chang MC.<br />

Relationship of early hyperglycemia to mortality in trauma<br />

patients. J Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical <strong>Care</strong> 2004; 56:<br />

1058-62.<br />

4. Van den Berghe, G; Wouters, P; Weekers, F et al. <strong>Intensive</strong><br />

Insulin <strong>The</strong>rapy in Critically Ill Patients. NEJM 2001. 345:<br />

1359-1367.<br />

5. Cariou, A; Vinsonneau, C; Dhainaut, J-F. Adjunctive therapies in<br />

sepsis: An evidence-based review. CCM 2004; 32: S562-S570.<br />

6. <strong>The</strong> Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network: Ventilation<br />

with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal<br />

volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress<br />

syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1301-1308.<br />

7. Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al: Efficacy and safety<br />

of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N<br />

Engl J Med 2001; 344: 699–709<br />

8. Annane D. Sebille V. Charpentier C. et al. Effect of treatment<br />

with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on<br />

mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA 2002; 288(7):<br />

862-71.<br />

9. http://www.survivingsepsis.org/<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

Surveys & Audits continued 19<br />

An Audit and Review of Hypoglycaemia<br />

in Critical <strong>Care</strong><br />

A N Thomas, E M Boxall, G Sabbagh, Dr J<br />

Eddleston, T Dunne, A Stevens, P Murphy<br />

Summary<br />

<strong>The</strong> incidence of hypoglycaemia during critical<br />

illness was audited by asking staff across a critical<br />

care network to complete pre-printed forms attached<br />

to glucose vials used to treat this complication.<br />

Twenty eight episodes were identified in 2764<br />

patient days, with a median blood glucose 2.3<br />

mmol.l -1 , (range 1.3 to 4.0 mmol.l -1 ). A more<br />

complete record of the circumstances associated<br />

with hypoglycaemia was obtained than from<br />

reviewing 22 unstructured critical incident reports.<br />

<strong>The</strong> importance of maintaining calorie intake and<br />

monitoring night time glucose were identified as<br />

potentially preventative measures in 76<br />

hypoglycaemic episodes. A risk register was<br />

produced to provide recommendations on how such<br />

events can be avoided. Details of the database and<br />

pre-printed forms can be found on the ICS website 1 .<br />

Key Words<br />

Glucose, hypoglycaemia, insulin, intensive care,<br />

adverse events, critical incident, glucometer.<br />

Tight control of blood glucose has been shown to<br />

improve survival and reduce morbidity in critical<br />

illness 2 . <strong>Intensive</strong> insulin protocols are, however,<br />

associated with the risk of hypoglycaemia 2,3,4 .<br />

This paper describes a structured method of auditing<br />

hypoglycaemia and reviews the circumstances<br />

associated with hypoglycaemic episodes. A<br />

literature review revealed other potential situations<br />

where hypoglycaemia may occur; these situations<br />

are described and strategies to minimise these risks<br />

are discussed.<br />

Methods<br />

<strong>The</strong> study was part of a wider investigation into<br />

intravenous drug administration in critical care,<br />

conducted with local research ethics committee<br />

approval across the Greater Manchester critical care<br />

network. Pre-printed forms (available on the ICS<br />

web site 1 ) requesting details of hypoglycaemic<br />

episodes were attached to vials of strong glucose<br />

solution used in their treatment. Staff accessing<br />

these vials to treat hypoglycaemia completed the<br />

forms and placed them in their unit’s critical incident<br />

box. <strong>The</strong> data was entered into an Access database<br />

(Microsoft Access, Microsoft inc. Seattle USA). <strong>The</strong><br />

study was conducted for a 4-week period in units<br />

across the network at times staggered between the<br />

start of February and mid April 2005. To obtain a<br />

larger sample of hypoglycaemic episodes than would<br />

be found in such a short audit period, critical incident<br />

forms in one ICU were hand-searched to identify all<br />

hypoglycaemic episodes reported from August 2002<br />

until January 2005. For similar reasons, a second<br />

unit also prospectively reviewed their observation<br />

charts during March 2004 to identify all episodes<br />

where the blood glucose fell below 3.0 mmol.l -1 .<br />

We therefore collected episodes of hypoglycaemia<br />

by prospective audit using pre-printed forms, by<br />

retrospective review of critical incidents, and by<br />

review of observation charts. <strong>The</strong> information from<br />

all of the episodes identified using these 3 methods<br />

were then entered on an SPSS spreadsheet (SPSS<br />

for Windows 11.4. SPSS inc. Chicago Il) for<br />

subsequent analysis.<br />

Results<br />

A total of 76 hypoglycaemic episodes were<br />

identified, 28 from completed pre-printed from the<br />

glucose vials, 26 from the retrospective review of<br />

critical incidents and 22 from the prospective chart<br />

review. <strong>The</strong> median blood hypoglycaemic level<br />

recorded using the pre-printed forms was 2.3 mmol.l<br />

-1<br />

(range 1.3 to 4.0 mmol.l -1 ). Reports were<br />

received from 8 intensive care units with a median of<br />

3 per unit (range 1 to 6). <strong>The</strong>se units had a total of<br />

97 beds open at the time with an occupancy rate of<br />

95%, so the 28 episodes occurred in approximately<br />

2764 bed days. All of the units were using tight<br />

glucose control protocols (target range 4.0 to 8.0<br />

mmol.l -1 ). <strong>The</strong> median hypoglycaemic level for the<br />

single unit retrospective record review was 2.1<br />

mmol.l -1 (range 1.1 – 3.9 mmol.l -1 ).<br />

To increase the sample size and facilitate<br />

identification of factors associated with<br />

hypoglycaemia we included results from previous<br />

hypoglycaemia critical incidents and a retrospective<br />

chart review with the main audit from the glucose<br />

bottle forms (76 episodes in total). From within this<br />

combined record the median hypoglycaemic level at<br />

the time of recording was 2.5 mmol.l -1 (range 1.1-4.0<br />

mmol.l -1 ). <strong>The</strong> median blood glucose concentration<br />

recorded before the episode of hypoglycaemia was<br />

5.4 mmol.l -1 (range 2.4 – 13 mmol.l -1 ) in the 60<br />

incidents where this information was available.<br />

<strong>The</strong> median time between this reading and the<br />

hypoglycaemic episode was 3 hours (range 1 to 6<br />

hours) in the 39 records where this could be<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>2006</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Journal of the <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Society</strong>

<strong>Volume</strong> 7 <strong>Number</strong> 2<br />

20<br />

Surveys & Audits continued<br />

calculated. Of the 32 records where it was<br />

recorded, 25 had been receiving insulin for less than<br />

24 hours and 17 for more than 24 hours. In the<br />

63 records where the time of hypoglycaemia was<br />

recorded, 35 were reported between 21:00 and<br />

07:00, 17 were reported between 07:00 and 14:00<br />

and 11 were reported between 14:00 and 21:00. In<br />

3 of 10 patients who were not receiving insulin at the<br />

time of the incident other conditions were known to<br />

have caused hypoglycaemia. In the 44 patients<br />

where the insulin dose was recorded the median<br />

dose was 3 units/hr (range 1 to 14 units/hr) at the<br />

time of hypoglycaemia. <strong>The</strong> method of glucose<br />

measurement was recorded in 50 patients; in 31<br />

glucose was measured using a blood gas analyser,<br />

20 by glucometer (both methods used in 1 case).<br />

One glucometer reading was checked by laboratory<br />

measurement. Where the information was recorded,<br />

28 of 71 patients had experienced interruptions to<br />

their calorie intake in the previous two hours, and<br />

14 of 50 patients were receiving steroids.<br />

Using the old reported critical incidents it was<br />

not possible to establish the time between<br />

measurements or the method of measurement for<br />

any of the incidents. <strong>The</strong> measurement intervals<br />

could, however, be established in 18 of 28 episodes<br />

reported using the pre-printed forms, all of which<br />