2001â2002 - California Sea Grant - UC San Diego

2001â2002 - California Sea Grant - UC San Diego

2001â2002 - California Sea Grant - UC San Diego

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

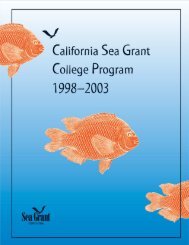

The Abalone Farm may have as many as 2 million<br />

abalone growing in concrete tanks along the coast.<br />

The company is working with scientists to develop oral<br />

antibiotic therapies for treating withering syndrome.<br />

Photos: Ray Fields, The Abalone Farm, Inc.<br />

“We were very excited about working with <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Grant</strong><br />

on this project,” said Ray Fields, president of The<br />

Abalone Farm in Central <strong>California</strong>, the nation’s<br />

largest abalone producer. “We lost half a million<br />

abalone in the 1997–98 El Niño. It was a significant<br />

loss.”<br />

“Because of this <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Grant</strong> research, there is now a<br />

treatment for the bacterium that causes withering<br />

syndrome, antibiotics administered in abalone feed,”<br />

Fields said. “It has been a great collaboration.”<br />

The Abalone Farm donated abalone for experiments<br />

and allowed research to be conducted at its<br />

facility.<br />

In terms of curing the disease, antibiotics<br />

are showing promise in cultured abalone. In<br />

an ongoing <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Grant</strong> project, Friedman is<br />

collaborating with The Abalone Farm in<br />

Morro Bay to develop an antibiotic treatment<br />

put in abalone feed. They have shown that a<br />

two-week treatment of oxytetracycline (an<br />

antibiotic that already has FDA approval for<br />

use in aquaculture) protects an abalone for<br />

the duration of its culture cycle. In other<br />

words, farms have to give an abalone antibiotics<br />

only once in its life.<br />

As treatment for farmed abalone continues<br />

to be developed, scientists are also looking to<br />

understand the conditions in the natural<br />

world that put wild abalone at risk. Stress is<br />

believed to lower abalone’s resistance to<br />

disease. The main sources of stress in an<br />

abalone’s life are warm water (abalone thrive<br />

in colder waters) and lack of food. El Niño<br />

events stress abalone on both fronts, since<br />

abnormally warm waters also kill kelp, their<br />

main food.<br />

To better understand these stresses, <strong>Sea</strong> <strong>Grant</strong> has<br />

funded Friedman, in collaboration with researchers at<br />

<strong>UC</strong> Davis, to identify the connection between diet, water<br />

temperature and withering syndrome. The scientists’<br />

preliminary results show that warm water plays a much<br />

greater role in triggering disease than does extreme<br />

reduction in food, even starvation. Abalone infected<br />

with the bacterium and then starved did not develop<br />

disease, while those placed in warm-water tanks did. If<br />

the withering syndrome bacterium continues to spread,<br />

global ocean warming or a series of intense El Niño<br />

events could truly imperil the survival of wild abalone in<br />

<strong>California</strong>, Friedman said.<br />

9